Introduction: When Hustle Culture Meets Human Limits

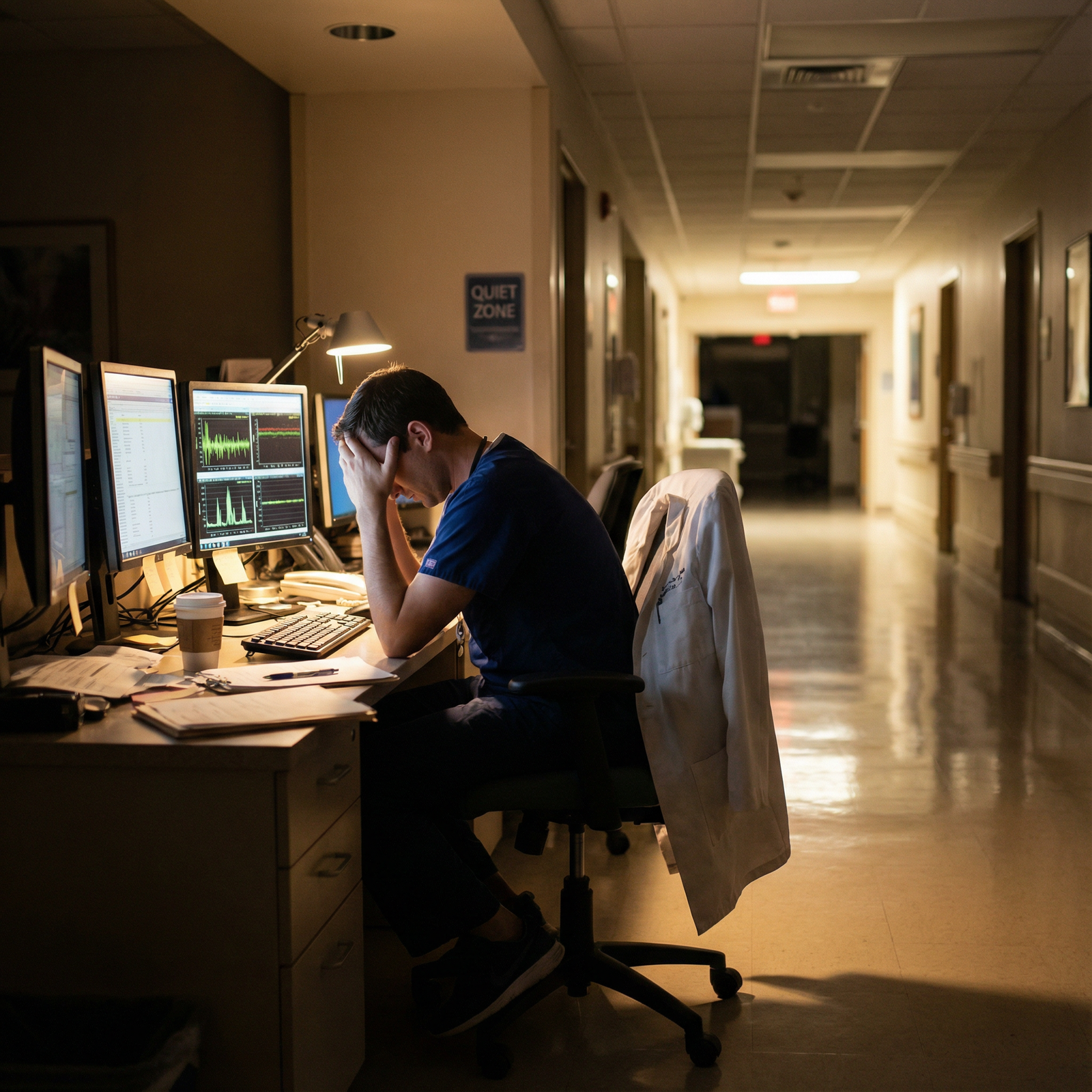

In medicine and other high-stakes professions, working hard is considered a virtue—and often a necessity. Long shifts, overnight calls, and back-to-back responsibilities become a badge of honor. For many medical students, residents, and attending physicians, the unspoken expectation is clear: the more you sacrifice, the more dedicated you must be.

Yet there is a breaking point.

Overworking does not just cause fatigue; it silently erodes your physical health, Mental Health, relationships, and long-term Productivity. The result is burnout—a state of emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion that can derail careers, compromise patient care, and diminish quality of life.

This deep dive explores the hidden costs of overworking and burnout, particularly in healthcare, and offers practical, evidence-informed strategies for sustainable Stress Management, Work-Life Balance, and recovery. The goal is not to ask you to “care less,” but to help you care more sustainably—for your patients and for yourself.

Understanding Burnout: Beyond Being “Tired”

What Is Burnout?

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines burnout as an “occupational phenomenon” resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is not simply being overworked for a week or going through a tough rotation; it is persistent, cumulative, and multidimensional.

Burnout is characterized by three core components:

Exhaustion

- Deep physical and emotional depletion

- Feeling drained before the day even starts

- Difficulty recovering even after sleep or days off

Cynicism (Depersonalization)

- Emotional distancing from work, patients, or colleagues

- Irritability, frustration, or a “what’s the point?” mindset

- Viewing patients or tasks as objects rather than people with stories

Reduced Professional Efficacy

- Sense of incompetence or “I’m not good enough”

- Feeling that your work does not matter or achieve meaningful results

- Declining confidence in skills you previously felt comfortable with

In a medical context, this can look like a once-enthusiastic student or resident becoming detached on rounds, dreading cases they used to find exciting, or starting to question whether they chose the right profession altogether.

Why Burnout Is So Common in Medicine

Multiple systemic, cultural, and personal factors converge in healthcare to create fertile ground for burnout:

Excessive Workload and Long Hours

- Night float, 24–28 hour calls, back-to-back clinic days

- Documentation burdens and EMR “pajama time” after shifts

- Administrative tasks layered on top of clinical responsibilities

High Stakes and Constant Responsibility

- Fear of making mistakes that could harm patients

- Emotional burden of bad outcomes, death, and difficult conversations

- Chronic exposure to suffering and trauma

Lack of Control and Autonomy

- Little say in scheduling, caseload, or team structure

- Conflicting demands from attendings, patients, and administration

- Inflexible training requirements and evaluation pressures

Dysfunctional or Unsupportive Work Environments

- Hierarchical cultures that normalize humiliation or “pimping”

- Bullying, discrimination, or microaggressions

- Lack of psychological safety to ask for help or admit uncertainty

Unclear or Conflicting Expectations

- Ambiguous role definitions, especially between levels of training

- Mixed messages: “Take care of yourself” vs. “Do whatever it takes”

- Pressure to excel clinically, academically, and personally—simultaneously

Poor Work-Life Balance

- Shifts that bleed into personal time due to charting and messages

- Rotations that make exercise, sleep, or socializing feel impossible

- Internalized guilt about not “doing more” when off-duty

Over time, these stressors accumulate. Without effective Stress Management and organizational support, burnout becomes not the exception, but the default outcome.

The Hidden Costs of Overworking and Burnout

Burnout is often misinterpreted as a personal weakness or lack of resilience. In reality, it has broad and profound consequences—for individuals, teams, patients, and healthcare systems.

1. Physical Health Deterioration

Chronic overwork and inadequate recovery are not just uncomfortable; they are physiologically harmful.

Persistent Fatigue and Sleep Deprivation

- Impaired reaction times equivalent to being legally intoxicated

- Increased risk of motor vehicle accidents, needle-stick injuries, and errors

- Non-restorative sleep, even on off days, due to chronic stress

Cardiovascular Risk

- Elevated blood pressure and heart rate from prolonged sympathetic activation

- Increased risk of hypertension, coronary artery disease, and stroke

- Higher incidence of metabolic syndrome and obesity due to disrupted eating and sleep patterns

Weakened Immune Function

- More frequent viral illnesses (colds, flu, COVID)

- Slower recovery from infections or surgeries

- Chronic inflammation contributing to long-term disease risk

Somatic Symptoms

- Headaches, migraines, gastrointestinal disturbances (IBS, reflux)

- Chronic pain, muscle tension, back and neck strain

- Menstrual irregularities or worsening of chronic conditions (e.g., autoimmune disease)

For residents and physicians who often dismiss their own symptoms, these physical warning signs are easy to ignore—until they force time off or acute illness.

2. Mental Health Consequences

Burnout and Mental Health are tightly intertwined. While burnout is not classified as a mental disorder, it can both mimic and fuel clinical conditions:

Anxiety Disorders

- Constant worry about performance evaluations, patient outcomes, or making mistakes

- Somatic anxiety: racing heart, shortness of breath, insomnia

- Fear of being “found out” as inadequate (imposter syndrome)

Depression

- Loss of interest in work, hobbies, and relationships

- Feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, or worthlessness

- Changes in appetite, sleep, and energy levels

Emotional Exhaustion and Compassion Fatigue

- Numbness or detachment from patients’ suffering

- Irritability toward colleagues, patients, and even family

- Difficulty accessing empathy you know you once had

Risk of Substance Misuse and Maladaptive Coping

- Using alcohol, sedatives, or stimulants to cope with stress, sleep, or performance demands

- Overreliance on caffeine or energy drinks for basic functioning

- Escalating use leading to dependency or impaired functioning

Left unaddressed, burnout can progress into severe depression or anxiety requiring urgent professional intervention—and may even increase the risk of suicidal ideation, particularly in physicians.

3. Reduced Productivity, Performance, and Creativity

Ironically, overworking in pursuit of higher Productivity usually backfires.

Diminished Quality of Work

- More frequent clinical errors, overlooked details, or charting mistakes

- Slower decision-making, difficulty prioritizing, and cognitive “fog”

- Greater need for supervision or correction, despite working longer hours

Inefficient Use of Time

- Spending more hours to accomplish the same tasks

- Getting stuck in low-yield activities while avoiding complex tasks

- Rework and corrections consuming additional time and energy

Decreased Innovation and Problem-Solving

- Less creativity in clinical reasoning or research design

- Reduced capacity to think “big picture” or system-level improvements

- Stagnation in career development due to sheer exhaustion

Beyond individual performance, burnout contributes to team-level dysfunction: more handoff errors, miscommunications, and breakdowns in collaboration.

4. Strained Relationships and Social Isolation

Burnout rarely stays at work; it seeps into every part of life.

At Work

- Increased conflict or tension with colleagues, nurses, or supervisors

- Difficulty receiving feedback or participating constructively in rounds

- Withdrawal from informal conversations, teaching, or mentorship

At Home

- Cancelling plans with friends and family due to fatigue or call schedules

- Emotional unavailability to partners, children, or loved ones

- Resentment building on both sides as relationships become one-sided

Loss of Support Networks

- Gradual disengagement from hobbies, communities, or support groups

- Feeling like “no one outside medicine understands”

- Intensification of burnout as social buffers disappear

For trainees, this isolation can be especially dangerous, as peers and loved ones are often the first to notice warning signs and encourage seeking help.

5. Financial and System-Level Costs

While working more may temporarily increase income (extra shifts, moonlighting), burnout carries significant hidden financial costs.

Individual Costs

- Out-of-pocket expenses for therapy, medications, or medical care

- Lost income from sick leave, medical leave, or reduced hours

- Potential career shifts, leaving higher-paying roles due to unsustainable stress

Institutional Costs

- High turnover and recruitment costs when clinicians leave due to burnout

- Reduced patient satisfaction and loyalty

- Increased malpractice risk associated with errors, poor communication, and impaired performance

For healthcare organizations, burnout is not just a wellness issue; it is a major driver of lost Productivity, safety concerns, and financial loss.

Recognizing Burnout in Yourself and Others

Awareness is the first step toward recovery. Burnout often creeps in gradually, making it easy to rationalize or deny.

Common Warning Signs

Look for patterns that persist for weeks to months, not just a rough call weekend:

Emotional Red Flags

- Irritability, frustration, or feeling “on edge” most days

- Sense of dread before shifts or clinic days

- Emotional numbness or feeling disconnected from patients

Behavioral Changes

- Procrastination, arriving late, or leaving as soon as possible

- Social withdrawal—skipping team meals, ignoring messages, avoiding calls

- Increased use of alcohol, sedatives, stimulants, or excessive caffeine

Performance Declines

- Falling behind on notes, orders, or reading

- More frequent mistakes or near misses

- Feedback from attendings or peers that “something seems off”

Physical Symptoms

- Persistent fatigue despite sleep opportunities

- Headaches, GI issues, unexplained aches and pains

- Frequent minor illnesses or slow recovery from common infections

Simple Self-Assessment Questions

Ask yourself honestly:

- Do I feel emotionally empty or detached at work most days?

- Do I regularly think, “I can’t keep doing this,” even if I don’t say it out loud?

- Have I lost my sense of purpose or meaning in the work I used to value?

- Am I more cynical or negative with colleagues or patients than I used to be?

- Do I rely on substances, food, or mindless scrolling just to “numb out”?

If several of these resonate consistently, it may be time to take burnout seriously and explore support options.

Looking Out for Colleagues

In a team-based environment, noticing burnout in others is equally important:

- Sudden drop in engagement or participation on rounds

- Dramatic change in mood, affect, or reliability

- Repeatedly volunteering for extra shifts beyond what’s sustainable

- Dark humor that may hint at deeper distress

Compassionate, nonjudgmental check-ins—“You haven’t seemed like yourself lately; how are you really doing?”—can open the door for someone to seek help.

Strategies to Prevent and Recover from Burnout

Addressing burnout requires both individual and systemic strategies. While you may not control your entire work environment, there are concrete steps you can take to protect your health and Work-Life Balance.

1. Redefine and Protect Work-Life Balance

Perfect balance is unrealistic in medicine, but intentional boundaries can make life more sustainable.

Set Clear Work Boundaries

- Designate “no-charting” times at home when possible

- Silence non-urgent notifications during sleep and protected personal time

- Use out-of-office messages for vacations—and truly disconnect when off

Create Small but Non-Negotiable Rituals

- A 10–15 minute daily walk, regardless of rotation

- Weekly call or meal with a friend or family member

- A consistent pre-sleep routine to signal your body to rest

Use Time Management Techniques

- Pomodoro technique (25 minutes focused work, 5-minute break) for charting or studying

- Task batching (e.g., responding to all messages twice daily rather than constantly)

- Prioritizing “must-do” vs “nice-to-do” tasks to avoid perfectionism-driven overwork

2. Practice Evidence-Based Stress Management

You cannot eliminate stress in healthcare—but you can improve how your body and mind respond to it.

Mindfulness and Brief Practices

- 3-minute breathing exercises between patients or cases

- Mindful handwashing or walking from one unit to another

- Apps (e.g., Headspace, Calm, Insight Timer) for guided meditations, even 5 minutes at a time

Physical Activity as Medicine

- Short, high-yield workouts (10–20 minutes) several times a week

- Stretching routines for neck and back between notes or at the end of the day

- Walking meetings or taking the stairs when possible to embed movement

Restorative Sleep Hygiene

- Dark, cool, quiet sleep environment—especially for post-call days

- Limiting screens 30–60 minutes before bed when possible

- Strategic caffeine use (avoiding late-day intake that disrupts sleep)

Healthy Coping vs. Numbing

- Journaling, debriefing with peers, or reflective writing after hard cases

- Creative outlets (music, art, writing) that help process emotions

- Replacing doom-scrolling with intentional, time-limited leisure activities

3. Invest in Professional Growth and Meaning

Feeling stagnant or disconnected from purpose accelerates burnout. Reconnecting with meaning can be protective.

Clarify Your “Why”

- Reflect on why you chose medicine and what aspects of it still resonate

- Keep patient notes, thank-you cards, or meaningful moments as reminders

- Engage in roles that align with your values (teaching, advocacy, QI projects)

Seek Mentorship and Sponsorship

- Identify mentors who model a healthy, sustainable career path

- Ask directly about how they manage boundaries and balance

- Seek sponsors who can help shape a role or schedule aligned with your goals

Pursue Targeted Professional Development

- Attend workshops or conferences that genuinely interest you—not just for your CV

- Develop skills outside direct clinical care (leadership, communication, QI, teaching)

- Consider career paths or niches that better fit your temperament and values

4. Build a Supportive Network

No one gets through training or practice alone.

Peer Support

- Informal debriefs after difficult cases or codes

- Resident wellness groups or peer support programs, if available

- Group chats that are more than just schedule-swapping—spaces for honest sharing

Family and Friends

- Explain your schedule constraints but also communicate when you are truly free

- Be explicit about the kind of support you need (listening vs. problem-solving)

- Avoid only talking about work; protect some space for non-medical identity

Use Institutional Resources

- Employee assistance programs (EAP) or resident wellness services

- Confidential counseling services for trainees and staff

- Wellness committees or initiatives that offer structural changes (e.g., protected time, meal coverage, improved scheduling)

5. When and How to Seek Professional Help

Self-care is important but not always sufficient. Knowing when to involve professionals is vital.

Consider seeking professional help if:

- You experience persistent hopelessness, apathy, or thoughts of self-harm

- Anxiety, sleep disturbance, or mood symptoms significantly impair function

- Substance use has escalated or feels out of your control

- Burnout symptoms have not improved despite sustained efforts at change

Options include:

Individual Therapy

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for anxiety, perfectionism, or negative thought patterns

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for aligning actions with values despite stress

- Trauma-informed approaches for those exposed to repeated traumatic events

Group or Peer Support Programs

- Physician or trainee-specific groups that normalize experiences

- Balint groups focused on the physician-patient relationship and emotional processing

Occupational Health and Leave Options

- Discussing workload adjustments, schedule changes, or temporary leave

- Exploring accommodations for ongoing health conditions impacting performance

Seeking help is not a sign of weakness or lack of dedication; it is a professional responsibility—to yourself, your patients, and your team.

FAQs on Burnout, Overworking, and Work-Life Balance in Medicine

1. How can I tell the difference between normal stress and true burnout?

Normal stress is typically time-limited, linked to a specific situation (e.g., exams, a tough rotation), and improves with rest or when circumstances change. Burnout is more pervasive and persistent, characterized by:

- Ongoing exhaustion, even after days off

- Growing cynicism or detachment toward work and patients

- Feeling ineffective or that nothing you do makes a difference

If these symptoms have lasted weeks to months and are affecting multiple areas of life, it is likely more than “just a busy month.”

2. Is burnout inevitable during residency or a demanding medical career?

No. Burnout is common, but not inevitable. Certain environments and cultures normalize suffering and overwork, which increases risk. However, programs that emphasize reasonable scheduling, psychological safety, mentorship, and structural wellness support can significantly reduce burnout rates. On an individual level, setting boundaries, seeking mentorship, and practicing consistent Stress Management can make a substantial difference.

3. Can improving productivity actually reduce burnout, or does it make things worse?

It depends on your approach. Productivity strategies that help you work smarter (e.g., reducing unnecessary tasks, batching, prioritizing, using templates effectively) can free up time for rest and personal life, indirectly reducing burnout. However, if you use every gain in efficiency to take on more work or say “yes” to everything, increased productivity can accelerate burnout. The key is to use productivity gains to create space for recovery and meaningful activities, not just more output.

4. What if my workplace culture discourages talking about burnout or mental health?

Unfortunately, stigma remains a barrier in many medical settings. You still have options:

- Seek confidential services outside your institution if you’re concerned about privacy

- Connect with trusted mentors or peers who are open to these conversations

- Utilize anonymous helplines, national physician support services, or online therapy platforms

- Document your experiences and stressors in case you later need to advocate for accommodations or changes

You cannot always change the culture alone, but you can choose not to sacrifice your health to fit into an unhealthy system.

5. Can burnout be reversed, or does it permanently damage my career?

Burnout is reversible, especially when recognized early and addressed comprehensively. Many physicians and trainees recover fully and go on to build fulfilling, sustainable careers—sometimes with new boundaries, roles, or specialties that better align with their values. Recovery may require:

- Adjusting workload and expectations

- Engaging in therapy or counseling

- Reconnecting with purpose and meaningful aspects of medicine

- Restructuring your life to support genuine Work-Life Balance

What matters most is not whether you have experienced burnout, but how you respond and what you learn from it moving forward.

By understanding the hidden costs of overworking and taking burnout seriously, you protect not only your own well-being but also the safety, compassion, and excellence your patients deserve. Sustainable medicine is possible—but it starts with acknowledging that you are human, not a machine, and designing a career that respects both your limits and your aspirations.