Introduction: Medical Writing as a Modern Healthcare Career

In today’s data-driven healthcare ecosystem, the ability to translate complex science into clear, accurate content is a core professional skill—and an increasingly attractive career path. Medical writing sits at the intersection of medicine, Scientific Communication, and Clinical Research, supporting everything from drug development to patient education and Regulatory Affairs.

To many medical students, residents, and clinicians exploring alternative medical careers, “medical writer” can sound vague or niche. In reality, it’s a broad, dynamic field with diverse roles, work environments, and long-term career trajectories. Understanding what a real workday looks like can help you decide whether this path fits your interests, strengths, and lifestyle goals.

This expanded guide walks through a typical day in the life of a medical writer, highlights essential skills, and explains how medical writing integrates into broader healthcare careers—especially for those considering transitions out of full-time clinical practice.

What Is Medical Writing? Core Roles and Settings

Before looking at a daily schedule, it helps to clarify what “medical writing” actually includes. At its core, medical writing involves creating structured, accurate documents that communicate scientific and medical information to a defined audience.

Common Types of Medical Writing Projects

Medical writers work across a wide spectrum of document types, such as:

Research manuscripts

- Original research articles, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses

- Case reports and case series

- Review articles for clinical journals

Clinical Research documents

- Clinical trial protocols and amendments

- Investigator brochures

- Clinical Study Reports (CSRs)

- Informed consent forms and patient-facing trial materials

Regulatory Affairs documents

- Regulatory submissions such as INDs, NDAs, MAAs, CTAs

- Periodic Safety Update Reports (PSURs), Risk Management Plans (RMPs)

- Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPCs), labeling, and prescribing information

Medical education and communications

- Slide decks for conferences and CME events

- Speaker briefs and advisory board materials

- Scientific platforms, publication plans, and messaging frameworks

Patient and public-facing content

- Patient education brochures, websites, and handouts

- Health literacy–optimized content for apps and portals

- Press releases and lay summaries of clinical trials

Funding and strategy documents

- Grant applications and fellowship proposals

- Research proposals and concept notes

- Health technology assessment (HTA) summaries

Where Medical Writers Work

Depending on your interests and tolerance for structure vs. flexibility, you can find roles in:

- Pharmaceutical and biotech companies (in-house medical writing, Regulatory Affairs, or medical affairs teams)

- Contract Research Organizations (CROs)

- Medical communications agencies (med comms / med ed agencies)

- Academic institutions and research centers

- Healthcare systems and hospitals

- Nonprofits, public health organizations, and NGOs

- Freelance/consulting practice, either part-time or full-time

Each setting has its own pace and culture. For example, a CRO medical writer may spend most of their time on standardized Clinical Research documents under tight timelines, whereas an agency writer may balance multiple therapeutic areas and formats (slide decks, manuscripts, digital campaigns).

Morning: Structuring the Day for Deep Work

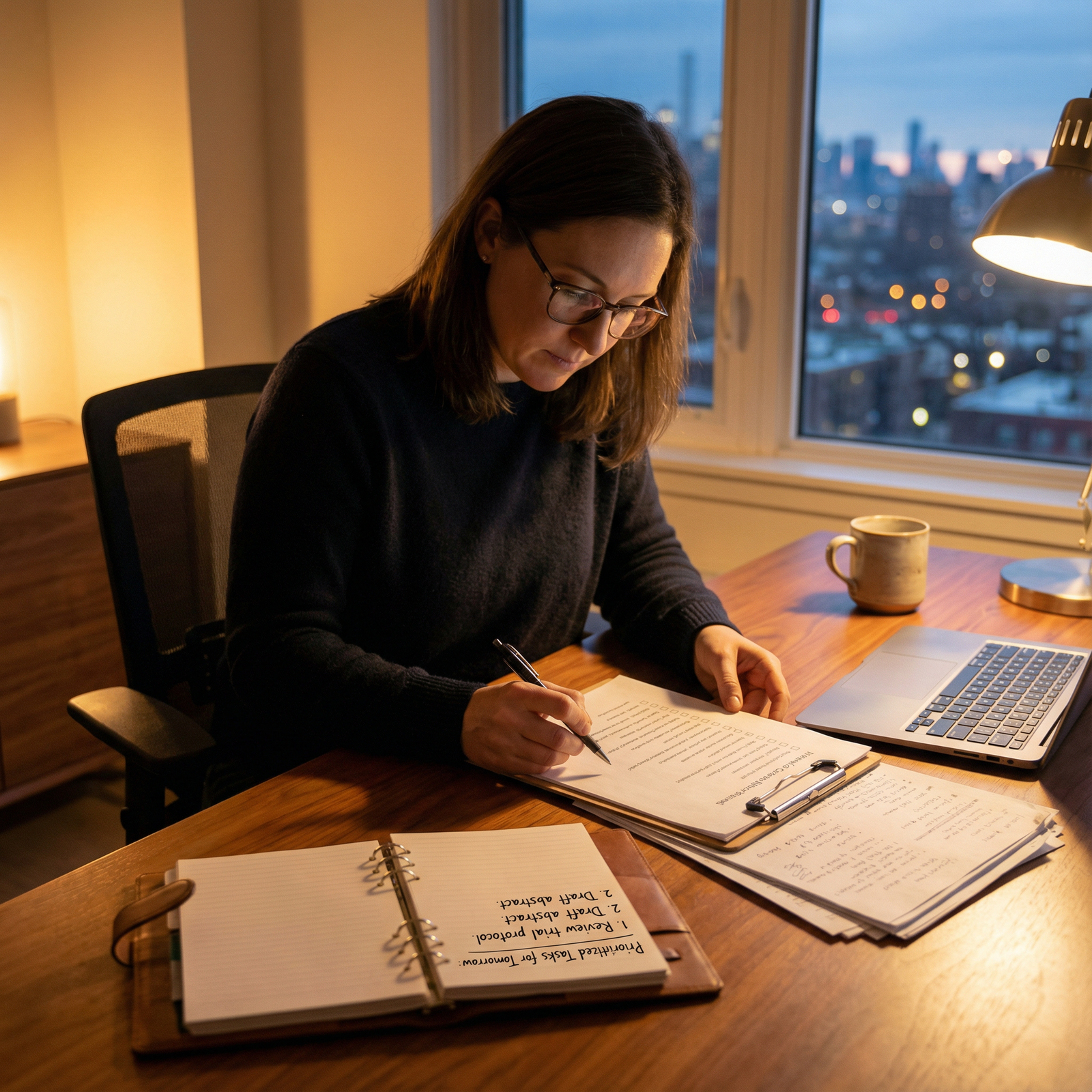

8:00 AM – Settling Into the Workspace

Many medical writers work fully remote or hybrid. A typical day starts in a home office or quiet workspace with:

- A quick review of email, project management tools (e.g., Asana, Jira, Trello), and shared calendars

- Checking for urgent client updates, document comments, or regulatory feedback

- Reviewing meeting schedules: internal stand-ups, client calls, or SME interviews

Writers coming from clinical backgrounds often find this part of the job surprisingly structured and predictable—no on-call shifts or night float—but still deadline-driven.

8:30 AM – Prioritizing Projects and Deadlines

Most medical writers juggle several active projects. A brief prioritization session might include:

- Reviewing Gantt charts, publication plans, or submission timelines

- Clarifying which documents are in:

- Concept/outline stage

- First-draft stage

- Revision or quality control (QC) stage

- Finalization and sign-off

Writers often break large projects into small, trackable tasks—for example:

- “Draft methods section for CSR”

- “Update safety narrative based on new data”

- “Revise introduction per reviewer comments”

Time-blocking is common: assigning 60–90-minute deep work blocks for primary writing tasks and shorter blocks for email, admin, and minor edits. This structure is critical for producing high-quality work consistently without burnout.

9:00 AM – Team Meetings or Client Check-Ins

Depending on your role:

In-house or CRO writer

- Join daily or weekly stand-ups with project managers, statisticians, and Regulatory Affairs colleagues

- Discuss status of protocols, CSRs, or regulatory deliverables

- Align on timelines for data availability, QC, and submissions

Agency writer

- Meet with account leads and medical directors

- Review client expectations for slide decks, manuscripts, or educational campaigns

- Clarify scientific messaging, target audience, and style preferences

Freelance medical writer

- Schedule client calls to confirm scope, deliverables, budget, and timelines

- Ask targeted questions about data sources, preferred references, and approval workflows

This early alignment prevents rework and helps ensure that your Medical Writing supports broader scientific communication and strategic objectives.

Midday: Deep Writing, Research, and Scientific Synthesis

10:00 AM – Focused Writing Session

Mid-morning is prime “deep work” time. This is when the core intellectual labor of medical writing happens: synthesizing data, building arguments, and crafting clear narratives.

Typical tasks include:

Drafting Results and Discussion sections for a journal manuscript

- Translating statistical outputs into clinically meaningful statements

- Integrating key literature to contextualize findings

- Ensuring alignment with target journal guidelines (e.g., CONSORT, PRISMA)

Developing Clinical Research documents

- Writing protocol sections (background, objectives, endpoints, statistical considerations)

- Creating or updating informed consent forms to meet ethical and readability standards

- Drafting narratives of adverse events or safety signals

Preparing Regulatory Affairs documents

- Summarizing efficacy and safety across multiple studies for an NDA or MAA

- Incorporating regulator feedback into an updated submission

- Ensuring content aligns with ICH guidelines and regional regulatory standards

Creating educational or patient-facing content

- Simplifying complex mechanisms of action into accessible visuals and text

- Tailoring language and tone to health literacy levels

- Fact-checking against current guidelines (e.g., ADA, ACC/AHA, NCCN)

Medical writers often switch between dense scientific detail and big-picture framing, which requires both precision and narrative skill.

11:30 AM – Literature Review and Fact-Checking

Effective Medical Writing is only as strong as its evidence base. Writers spend significant time on:

- Systematic or targeted literature searches (PubMed, Embase, clinicaltrials.gov)

- Reviewing clinical guidelines, consensus statements, and position papers

- Checking drug labels, SmPCs, and safety information

- Verifying data against original study reports or statistical outputs

For example, when drafting a grant application, a writer might:

- Assess the current standard of care and unmet needs

- Identify gaps in existing Clinical Research

- Support the proposal’s rationale with robust, recent references

Maintaining a structured reference system (EndNote, Zotero, Mendeley) and clear version control is vital for accuracy and audit-readiness.

12:30 PM – Lunch and Brief Reset

A genuine break—away from the screen—helps maintain focus for the afternoon. Many writers use this time for:

- Short walks or light exercise

- Catching up informally with colleagues (virtually or in person)

- Brief professional reading: newsletters from regulatory agencies, new trial results, or med comms blogs

This structured downtime supports long-term productivity and creativity.

Afternoon: Collaboration, Review Cycles, and Professional Growth

1:00 PM – Meetings with Subject Matter Experts (SMEs)

Afternoons often involve collaboration with:

Clinicians and principal investigators

- Clarifying nuances in trial design or interpretation of results

- Confirming clinical relevance of endpoints and outcomes

- Aligning on how conservative or assertive to be in conclusions

Biostatisticians

- Discussing statistical methods, sensitivity analyses, and limitations

- Ensuring correct representation of p-values, confidence intervals, and effect sizes

- Resolving discrepancies between tables, figures, and text

Regulatory Affairs and safety teams

- Aligning on labeling language and risk–benefit framing

- Addressing questions raised by regulators in previous submissions

- Confirming compliance with current regional regulations

Medical affairs and commercial teams (in med comms/industry roles)

- Clarifying key messages and target audiences

- Ensuring materials are scientific, balanced, and non-promotional when required

- Coordinating timelines for congresses, publications, and launches

These conversations sharpen the document’s scientific rigor and ensure that the content is accurate, compliant, and strategically aligned.

2:30 PM – Editing, Revisions, and Quality Control

Medical writing is highly iterative. A large part of the afternoon may be spent on:

Self-editing

- Improving clarity, flow, and logical structure

- Ensuring consistency in terminology, abbreviations, and units

- Checking adherence to style guides (AMA, journal-specific, or client-specific)

Peer review and QC

- Reviewing colleagues’ drafts for scientific accuracy and clarity

- Applying checklists for internal quality standards

- Verifying that document templates and formatting requirements are met

Incorporating feedback

- Integrating SME or client comments while preserving internal consistency

- Resolving conflicting feedback through clarification calls or written rationales

- Documenting major changes for audit trails in Regulatory Affairs contexts

Strong editing and critical appraisal skills are as important as initial writing ability. Over time, experienced writers develop a “quality radar” that speeds up this process significantly.

3:30 PM – Staying Current: Trends, Tools, and Professional Development

Successful medical writers treat learning as an integral part of their job. Regular activities might include:

Monitoring Regulatory Affairs updates

- FDA/EMA guidance documents

- ICH guideline revisions

- Regional regulatory changes affecting labeling or submissions

Tracking developments in key therapeutic areas

- Landmark Clinical Research publications

- New drug approvals and guideline updates

- Emerging technologies (digital therapeutics, AI in diagnostics)

Expanding skills in Scientific Communication

- Attending webinars or workshops on publication ethics, plain language summaries, or data visualization

- Exploring AI-assisted writing tools, reference managers, and statistical software

- Participating in professional associations (AMWA, EMWA, ISMPP)

This ongoing development not only improves document quality but also supports long-term career growth—into lead writer, therapeutic area expert, team manager, or strategic roles in healthcare communication.

Evening: Wrap-Up, Boundaries, and Work–Life Balance

5:00 PM – Daily Review and Planning for Tomorrow

As the day winds down, many medical writers:

- Log progress in project management systems

- Update document status (e.g., “sent to client,” “with SME,” “in QC”)

- Note blockers (e.g., pending data, missing references) for follow-up

- Create a prioritized list for the next day’s writing blocks and meetings

This brief planning ritual reduces cognitive load and helps maintain clearer work–life boundaries—especially important for remote roles.

5:30 PM – Self-Care, Hobbies, and Mental Health

Medical writing can be intense, with tight deadlines and high expectations for accuracy. To sustain performance, writers often:

- Engage in regular physical activity (runs, yoga, gym)

- Pursue creative hobbies (reading fiction, art, music) to counterbalance dense scientific work

- Set clear communication norms with clients/teams about after-hours availability

- Use time-blocking and “no meeting” periods to protect deep work and avoid chronic overtime

For clinicians transitioning to Medical Writing as an alternative healthcare career, this more predictable schedule and the ability to control one’s workload are often major benefits.

Essential Skills and Qualities of Successful Medical Writers

1. Advanced Writing and Editing Skills

- Ability to explain complex concepts clearly and concisely

- Strong command of grammar, syntax, and scientific style

- Flexibility to adjust tone for diverse audiences (regulators vs. patients vs. KOLs)

- Familiarity with common style guides (AMA Manual of Style, journal guidelines)

2. Solid Scientific and Clinical Understanding

- Background in life sciences, medicine, pharmacy, or related fields

- Comfort with study design, statistics fundamentals, and critical appraisal

- Ability to interpret Clinical Research data and draw appropriate conclusions

- Understanding of disease mechanisms, diagnostic pathways, and treatment options

3. Meticulous Attention to Detail

- Accurate transcription and interpretation of data (tables, figures, values)

- Consistent use of terminology, units, and abbreviations

- High standards for referencing, citation formats, and plagiarism avoidance

- Awareness of ethical considerations in publication and authorship

4. Time and Project Management

- Managing multiple parallel timelines and stakeholders

- Breaking complex documents into achievable milestones

- Communicating proactively about delays, dependencies, and risks

- Maintaining calm and quality under tight deadlines

5. Interpersonal and Communication Skills

- Working collaboratively with cross-functional teams (SMEs, statisticians, regulatory, commercial)

- Asking focused questions that clarify expectations and data gaps

- Giving and receiving feedback professionally

- Navigating conflicts in interpretation or messaging with diplomacy

These skills develop over time; very few writers are “fully formed” on day one. Structured feedback, mentorship, and deliberate practice are key to growth.

Pathways Into Medical Writing: Education and Early Experience

Educational Backgrounds

Most medical writers have at least a bachelor’s degree in a health-related or scientific discipline:

- Medicine (MD/DO), nursing, pharmacy (PharmD)

- Biology, biochemistry, pharmacology, public health

- Psychology, neuroscience, or related fields

Advanced degrees (Master’s, PhD, MD) can be advantageous for:

- High-level scientific content and Clinical Research writing

- Senior or specialized roles in Regulatory Affairs or publications

- Academic and grant-writing roles

However, a higher degree is not always mandatory—demonstrated writing skill and domain knowledge can be equally compelling.

Practical Steps to Get Started

Build a writing portfolio

- Volunteer to help with manuscripts, posters, or grants in your lab or department

- Write blog posts, patient information sheets, or educational materials

- Create sample documents (e.g., mock drug monograph, short review article)

Seek relevant training

- Short courses or certificates in Medical Writing or Scientific Communication

- Workshops from professional associations (AMWA, EMWA, ISMPP)

- Online courses in statistics, research methods, or Regulatory Affairs basics

Gain exposure to Clinical Research workflows

- Participate in research projects, even as a sub-investigator or data abstractor

- Assist with IRB submissions or informed consent forms

- Shadow research coordinators or regulatory staff if possible

Network strategically

- Join online groups and forums for medical writers

- Attend virtual or in-person conferences on Medical Writing and med comms

- Connect with writers on LinkedIn and ask informed questions about their career paths

These steps help you confirm your interest in Medical Writing and make you more competitive for entry-level roles.

Real-World Impact: How Medical Writers Shape Healthcare

Although medical writers often work behind the scenes, their contributions are central to modern medicine and the future of healthcare careers:

Enabling new therapies

- Regulatory documents and Clinical Research reports support drug and device approvals, bringing innovations to patients

Improving patient understanding and adherence

- High-quality patient education materials can enhance treatment adherence, reduce confusion, and improve outcomes

Supporting evidence-based practice

- Well-written guidelines, reviews, and educational content help clinicians stay current and make informed decisions

Protecting patient safety and ethics

- Clear safety narratives, risk management documents, and informed consent forms ensure ethical, transparent research

Advancing public health communication

- Accurate, accessible Scientific Communication during crises (e.g., pandemics) helps counter misinformation and build trust

For medical students or clinicians who enjoy both medicine and writing, this career offers a way to make broad, scalable contributions across populations—not just individual patients.

FAQ: Medical Writing Careers for Clinicians and Trainees

1. Do I need clinical experience to become a medical writer?

Clinical experience is helpful but not strictly required. It can be particularly valuable for:

- Interpreting Clinical Research and understanding real-world relevance

- Writing patient-facing materials with empathy and practicality

- Contributing to medical affairs or guideline development projects

However, many successful writers come from PhD or master’s-level research backgrounds without bedside experience. What matters most is your ability to understand medical science, think critically, and communicate clearly.

2. What is the difference between Regulatory Affairs writing and medical communications?

- Regulatory Affairs writing focuses on documents submitted to regulatory agencies (FDA, EMA, etc.): INDs, NDAs, CSRs, safety reports, labeling. It is highly structured, guideline-driven, and compliance-focused.

- Medical communications (med comms) emphasizes educational and strategic materials: manuscripts, conference posters, slide decks, training modules, and patient materials. It often involves more varied formats and audiences.

Your choice depends on your interest in structured documentation and regulations vs. broader Scientific Communication and education.

3. Is freelance medical writing a realistic option for residents or practicing clinicians?

Yes—with planning. Freelance Medical Writing can be:

- A side venture alongside residency or clinical practice

- A transition pathway out of full-time clinical work

- A long-term independent consulting career

Key considerations:

- Start with small, well-defined projects and clear scopes

- Develop reliable systems for time-tracking, contracts, and invoicing

- Be realistic about your available hours, especially during training

- Build a focused niche (e.g., cardiology education, oncology publications, regulatory writing for specific indications)

4. How can I stay up to date and grow in my medical writing career?

- Join professional associations (AMWA, EMWA, ISMPP)

- Subscribe to updates from regulatory bodies (FDA, EMA, MHRA, ICH)

- Follow key journals and societies in your therapeutic area(s) of focus

- Take periodic courses on statistics, data visualization, and new tools (including AI-assisted writing and literature screening)

- Seek mentorship from senior writers and be proactive in asking for structured feedback

5. What are typical career progression paths for medical writers?

Common pathways include:

- Junior/Associate Medical Writer → Medical Writer → Senior Medical Writer

- Lead or Principal Writer → Team Lead or Manager → Director of Medical Writing

- Specialization tracks, such as:

- Regulatory Affairs lead writer

- Publications and Scientific Communication strategist

- Therapeutic area expert (e.g., oncology, cardiology, neurology)

Some writers later pivot into broader healthcare careers such as medical affairs, Clinical Research management, or publication strategy.

Medical writing sits at a powerful crossroads: science, language, and patient care. For students, residents, and clinicians who love evidence and communication, it offers a rewarding, flexible path within the broader landscape of alternative medical careers—with tangible impact on how medicine is practiced and understood worldwide.