Introduction: Why Mindfulness Matters in Chronic Pain Management

Chronic pain—classically defined as pain persisting beyond three months or beyond normal tissue healing time—is one of the most challenging problems in modern Healthcare. It affects hundreds of millions of people worldwide, contributes substantially to disability, and is tightly interwoven with Mental Health conditions such as anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance. Traditional pain management strategies have relied heavily on pharmacological interventions, injections, and procedures. While these can provide relief, concerns about opioid dependency, side effects, limited long-term effectiveness, and cost have driven a search for safer, more holistic approaches.

Mindfulness has emerged as a key non-pharmacologic tool in contemporary Pain Management. Evidence from randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and neuroscience research supports the idea that training patients to shift how they relate to pain can reduce suffering—even when the underlying nociceptive input remains.

For medical students, residents, and practicing clinicians, understanding how to explain, recommend, and integrate mindfulness into care is increasingly essential. This article explores the role of mindfulness in managing chronic pain, the underlying mechanisms, and practical strategies to incorporate it ethically and effectively into clinical practice.

Understanding Mindfulness in the Medical Context

What Is Mindfulness?

In a medical context, mindfulness is best understood as a trainable mental skill: intentionally bringing one’s attention to present-moment experience with curiosity, openness, and without judgment. Jon Kabat-Zinn’s widely cited definition—“paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally”—has been central in bringing mindfulness into mainstream Healthcare and Mental Health care.

Key elements relevant to chronic pain include:

- Present-moment awareness: Noticing sensations, thoughts, and emotions as they arise, rather than being pulled into catastrophic future scenarios (“This will never get better”) or ruminations about the past.

- Non-judgmental stance: Observing pain (“tightness,” “burning,” “throbbing”) without immediately labeling it as “intolerable,” “unfair,” or “a sign of total failure.”

- Acceptance versus resistance: Cultivating willingness to feel what is already present, instead of engaging in constant struggle to avoid or suppress pain sensations.

Importantly, mindfulness does not mean passivity or resignation. It is an active, intentional practice that can support wiser decision-making, better self-care, and more flexible engagement in valued life activities despite ongoing pain.

Core Mindfulness Techniques for Chronic Pain

While “mindfulness” is often spoken of as a single construct, in clinical practice it includes a set of specific, teachable techniques that can be adapted to the needs and capacities of individual patients.

Common approaches include:

Mindful Breathing

- Focusing attention on the sensations of breathing (airflow in the nostrils, rise and fall of the chest or abdomen).

- Useful as a short, portable practice that patients can use during pain flares, procedures, or at bedtime.

Body Scan Meditation

- Systematically moving attention through different parts of the body—from toes to head or vice versa.

- Encourages awareness and acceptance of bodily sensations, including painful or tense regions, without immediate reaction.

Sitting or Walking Meditation

- Using the breath, bodily sensations, or sounds as anchors.

- Developing the skill of noticing when the mind wanders (e.g., to distressing thoughts about pain) and gently returning to the present moment.

Loving-Kindness (Compassion) Meditation

- Cultivating warmth and kindness toward oneself and others.

- Particularly helpful for patients with chronic pain who struggle with self-criticism, shame, or perceived stigma related to their condition.

Mindful Movement

- Gentle yoga, tai chi, or qigong, emphasizing awareness of movement, breath, and limits.

- Can be particularly valuable for patients who fear movement (kinesiophobia) due to pain, supporting graded exposure and confidence.

These techniques are adaptable. For example, a patient with severe back pain might begin with brief, reclined body scan meditations, while a patient with agitation or restlessness might respond better to short bouts of mindful walking.

The Mind-Body Connection in Chronic Pain

How Mindfulness Modifies Pain Perception

Pain is not just a simple reflection of tissue damage. Instead, it is a complex sensory and emotional experience shaped by:

- Past experiences

- Mood and stress levels

- Attention and expectations

- Beliefs about pain and illness

- Social and cultural factors

In chronic pain, central sensitization and maladaptive cognitive patterns (catastrophizing, hypervigilance) can amplify pain signals. Patients often describe a sense that pain has “taken over their life” and identity.

Mindfulness alters this dynamic by:

- Shifting attention: Training patients to notice that they can attend to breath, surroundings, or other sensations—even while pain is present—reducing pain’s dominance in awareness.

- Decoupling pain and suffering: Patients learn to distinguish the raw sensation (“sharp,” “pressure,” “heat”) from the secondary layers of narrative (“I am broken,” “This will ruin everything”), which often drive emotional distress.

- Reducing catastrophizing: By noticing thoughts as mental events rather than facts, patients can relate more flexibly to catastrophic predictions about future disability or hopelessness.

In practice, this might sound like a patient saying: “The pain is still there, but I’m not as overwhelmed by it,” or “I still have bad days, but I recover faster emotionally.”

Neuroplasticity and the Neuroscience of Mindfulness in Pain Management

Advances in neuroimaging have clarified that mindfulness can harness neuroplasticity—the brain’s capacity to reorganize itself—to reshape how pain is processed.

Studies have shown:

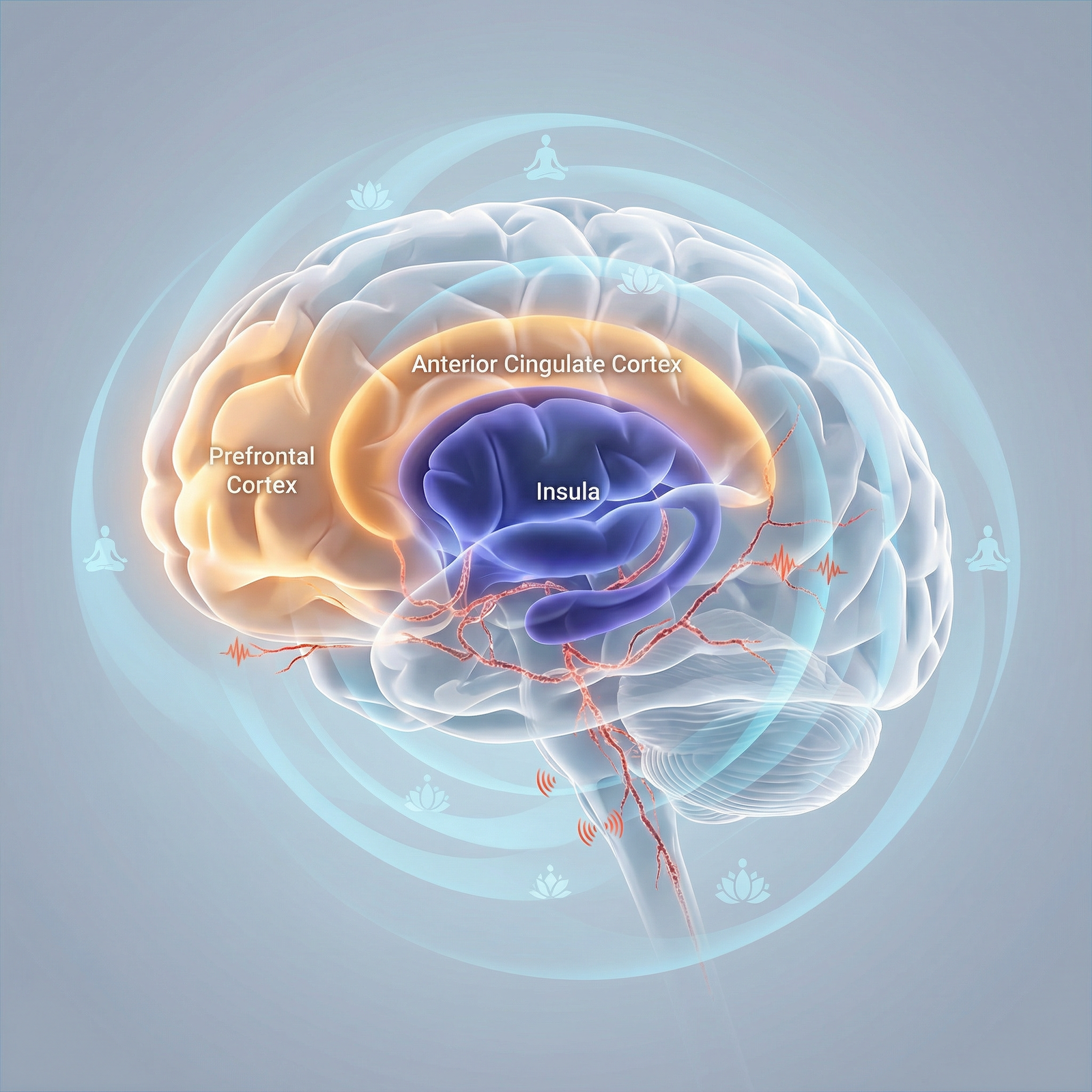

Reduced activation in threat and pain-related regions

- Mindfulness training is associated with reduced activation in the amygdala and certain regions of the insula and anterior cingulate cortex involved in the affective dimension of pain.

- This may translate into less distress and reactivity when pain signals arise.

Increased prefrontal and anterior cingulate engagement

- Regions involved in executive control, attention regulation, and emotion modulation become more active.

- Patients may experience greater “top-down” regulation—an increased sense of cognitive and emotional control over their response to pain.

Changes in pain modulation networks

- Mindfulness may enhance the brain’s intrinsic pain-inhibitory systems (e.g., periaqueductal gray pathways), improving endogenous pain modulation.

Alterations in default mode network (DMN) activity

- Reduced DMN hyperactivity—associated with rumination and self-referential thinking—can help decrease unhelpful, repetitive thinking about pain and disability.

The net effect is not necessarily the elimination of nociceptive input, but a reorganization in how that input is interpreted and integrated into conscious experience, leading to real-world reductions in reported pain intensity and improved functioning.

Evidence Base: Mindfulness as an Evidence-Based Intervention for Chronic Pain

Systematic Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Key Trials

Over the past two decades, a robust evidence base has developed around mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) for chronic pain and Mental Health outcomes.

Key findings include:

Global effect on pain and distress

- A meta-analysis of 38 studies published in Pain (2016) found that MBIs led to statistically significant reductions in pain severity and emotional distress, as well as improvements in quality of life.

- Although effect sizes are often modest, they are comparable to many pharmacologic interventions and come with minimal physiological risk.

Psychological benefits

- A review in The Journal of Pain (2013) showed that mindfulness training improves anxiety, depression, and pain acceptance—factors that are strongly predictive of disability and healthcare utilization.

Reduced pain interference and improved functioning

- In various studies, patients reported not just less pain intensity, but less interference of pain with sleep, work, relationships, and daily activities.

Long-term sustainability

- Follow-up data from some Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) studies show that benefits can persist months after program completion, particularly among patients who maintain some form of regular practice.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Other Clinical Programs

MBSR is the most widely studied mindfulness program in Healthcare:

Program structure

- Typically 8 weeks, with weekly 2–2.5-hour group sessions, a day-long retreat, and daily home practice.

- Includes body scan, sitting meditation, gentle yoga, and applied mindfulness in daily life.

Chronic pain conditions studied

- Fibromyalgia

- Chronic low back pain

- Osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis

- Chronic headache and migraine

- Neuropathic pain, cancer-related pain, and others

One widely cited randomized controlled trial in JAMA Internal Medicine (2016) on chronic low back pain showed that MBSR significantly improved pain-related functional limitations and pain intensity compared to usual care, with effects comparable to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Other program variants:

- Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT): Initially developed for recurrent depression, now applied to chronic pain with a stronger cognitive restructuring component.

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): Not strictly a mindfulness program, but heavily integrates mindfulness and acceptance to support values-based behavior change in chronic pain.

- Brief MBIs: Shorter protocols (e.g., 4 weeks, 20–30 minute sessions) are being developed to increase accessibility in busy clinical settings.

Practical Integration: Implementing Mindfulness in Clinical Pain Management

Assessing Patient Readiness and Setting Expectations

For practitioners, the first step is to gauge whether a patient is ready and willing to engage in mindfulness as part of Pain Management:

Explore beliefs and previous experience

- “Have you ever tried meditation, prayer, yoga, or relaxation techniques?”

- “What have you heard about mindfulness?”

Normalize and contextualize

- Position mindfulness as an evidence-based, skills-based training rather than a vague wellness trend.

- Clarify that it is compatible with most religious and cultural backgrounds, as it focuses on attention and awareness, not belief systems.

Set realistic expectations

- Emphasize that mindfulness is rarely an instant cure.

- Frame it as learning a new “mental physiotherapy,” where benefits usually emerge gradually over weeks to months of practice.

- Clarify that the goal is not necessarily to eliminate pain, but to reduce suffering, improve functioning, and expand life activities.

Providing Psychoeducation on Mindfulness and Chronic Pain

Brief, targeted psychoeducation can greatly increase patient engagement:

Explain the mind-body connection:

- How stress, sleep, mood, and attention patterns directly influence pain pathways.

- Use simple analogies: “Think of your nervous system as a volume knob; mindfulness can help turn down the overall volume, even if we can’t remove the signal completely.”

Use diagrams or handouts:

- Simple visuals of brain regions involved in pain and emotion.

- Flowcharts linking thoughts, emotions, muscle tension, and pain.

Link to other therapies:

- Show how mindfulness complements physical therapy (by reducing fear of movement), medication (by potentially lowering required doses), and psychotherapy (by enhancing emotional regulation).

Introducing Initial Mindfulness Practices in the Clinic

Practitioners don’t need to be certified meditation teachers to introduce foundational skills safely.

Options include:

Brief, in-session practices (2–5 minutes)

- Guided mindful breathing:

- “Let’s take 2 minutes to simply notice your breathing. You may still feel pain; see if you can allow both to be present.”

- Simple grounding:

- “Notice the feeling of your feet on the floor, your body supported by the chair. See if you can observe sensations without judging them as good or bad.”

- Guided mindful breathing:

Homework assignments

- Recommend starting with 5 minutes once or twice daily, gradually increasing to 10–20 minutes if tolerated.

- Provide or recommend:

- Reliable apps (e.g., Insight Timer, Headspace, Calm) with medically-oriented content

- Free online MBSR recordings (often hosted by academic centers)

- Handouts that outline simple scripts patients can follow

Mindful response to pain flares

- Teach patients a 3-step framework for acute pain spikes:

- Pause and notice: “This is a pain flare.”

- Breathe: Take 3–5 slow, intentional breaths.

- Label and allow: Name sensations (“throbbing in my leg”) and emotions (“frustration, fear”) without immediately reacting.

- Teach patients a 3-step framework for acute pain spikes:

Integrating Mindfulness into Multidisciplinary Treatment Plans

Mindfulness is most effective when embedded in a comprehensive, biopsychosocial Pain Management approach. Collaborate with:

- Physical therapists

- Coordinate graded activity or exercise with mindful awareness of sensations and pacing.

- Psychologists / psychiatrists

- Align mindfulness work with CBT, ACT, or trauma-informed therapy when indicated.

- Pain specialists and primary care

- Discuss possible medication adjustments as patients develop new coping skills, emphasizing safety and shared decision-making.

Practical tips:

- Include “mindfulness practice” as a formal treatment goal in the care plan.

- Use regular follow-ups to:

- Review practice frequency and challenges.

- Celebrate small gains (e.g., “I used mindful breathing during my commute and had fewer pain spikes.”).

- Problem-solve barriers (fatigue, time, skepticism).

Ethical Considerations and Professional Boundaries

From a Personal Development and Medical Ethics standpoint:

- Avoid overselling

- Present mindfulness as one tool among many, not a miracle cure or a substitute for appropriate medical evaluation and treatment.

- Respect autonomy and cultural background

- Some patients may have religious or cultural concerns; explore these respectfully and offer alternatives where appropriate (e.g., secular breathing exercises or relaxation training).

- Monitor for distress

- A small subset of patients may experience increased emotional distress when turning inward (e.g., trauma survivors).

- Screen for severe untreated PTSD, psychosis, or acute suicidality, and collaborate with mental health professionals if deeper work is needed.

- Maintain scope of practice

- If you are not formally trained in delivering full MBSR or MBCT programs, limit yourself to brief practices and referrals to qualified instructors or programs.

Real-World Application: An Expanded Case Study

Patient Profile

A 42-year-old woman with a 5-year history of fibromyalgia presents with widespread musculoskeletal pain, non-restorative sleep, fatigue, and significant anxiety about her ability to continue working. She has tried multiple medications with partial benefit and notable side effects. Her Pain Management team includes a rheumatologist, primary care clinician, and physical therapist.

Step 1: Assessment and Psychoeducation

- The clinician explores her past experience:

- She has tried “relaxation apps,” but felt she “couldn’t do it right” because her mind wandered.

- The clinician explains:

- Wandering attention is normal and part of the practice.

- Mindfulness will focus not on “making pain go away,” but on changing how she relates to pain and anxiety.

- The patient expresses openness but skepticism; this is acknowledged and normalized.

Step 2: Introduction of Mindful Breathing and Body Scan

- During a clinic visit, the clinician leads a 3-minute mindful breathing exercise:

- The patient notices both her breath and ongoing pain in her shoulders.

- She is encouraged to observe the pain without trying to fix it for those 3 minutes.

- She is given:

- A link to a reputable 10-minute guided body scan.

- A suggestion to practice once daily, preferably at night to support sleep.

Step 3: Gradual Progression and MBSR Referral

Over the next 4–6 weeks:

- She practices 10–15 minutes most evenings, with occasional missed days.

- She reports:

- Slight improvements in sleep onset.

- Feeling “a bit less panicky” when pain flares.

- The clinician then recommends an 8-week MBSR program at a nearby academic center.

- Goals: deepen practice, connect with peers, and integrate mindfulness with gentle yoga.

Step 4: Ongoing Monitoring and Team-Based Care

- Over six months:

- She completes MBSR, continues brief daily practice, and attends physical therapy with a focus on mindful movement.

- Medications are gradually optimized with input from the pain specialist.

- Outcomes:

- She reports a meaningful reduction in pain interference with daily activities.

- Pain intensity scores drop modestly, but her Pain Management self-efficacy markedly improves.

- She returns to part-time work with accommodations.

- She identifies mindfulness as “one of the first things I reach for when my symptoms spike.”

This case exemplifies how mindfulness, when integrated thoughtfully within multidisciplinary care, can support both symptom relief and psychological resilience.

FAQs: Mindfulness, Chronic Pain, and Clinical Practice

1. Which chronic pain conditions respond best to mindfulness-based interventions?

Mindfulness has shown benefit across a range of chronic pain conditions, including fibromyalgia, chronic low back pain, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic headache/migraine, neuropathic pain, and cancer-related pain. While effect sizes differ by condition and individual, the primary target is often pain-related distress and disability rather than complete elimination of nociceptive input. Patients with significant stress, anxiety, catastrophizing, or sleep disturbance often derive particular benefit.

2. How long does it usually take for patients to notice improvements from mindfulness practice?

Most structured programs (e.g., MBSR) report meaningful changes after 6–8 weeks of regular practice. Some patients notice early benefits within days or weeks—such as feeling calmer during flares or falling asleep more easily—while more substantial changes in pain interference, mood, and coping typically require consistent practice over months. Clinicians can help by framing mindfulness as a skill-building process, similar to physical rehabilitation or learning a new language.

3. Can mindfulness replace medications or procedural interventions for chronic pain?

Mindfulness is best viewed as a complementary rather than a replacement therapy. For many patients, it allows for safer, more gradual optimization of medications and may reduce reliance on high-dose analgesics, but it should not be used to justify the abrupt withdrawal of medically indicated treatments. Ethical Pain Management calls for an individualized, multimodal approach, combining pharmacologic, physical, psychological, and social interventions.

4. What if a patient becomes more distressed or overwhelmed during mindfulness practice?

Occasionally, turning inward can initially increase awareness of pain, difficult emotions, or traumatic memories. If patients report increased distress:

- Validate their experience and normalize that this can happen.

- Encourage shorter, more external-focused practices (e.g., noticing sounds or contact with the chair) rather than prolonged body scans.

- Consider screening for trauma, PTSD, or severe depression and collaborating with Mental Health professionals.

- Emphasize patient autonomy; they can pause, modify, or stop any practice that feels unsafe, and mindfulness should not be forced.

5. How can busy clinicians realistically incorporate mindfulness into routine care?

Even in time-constrained settings, clinicians can:

- Spend 1–2 minutes explaining the mind-body connection and suggesting a single simple practice (e.g., 5 minutes of mindful breathing daily).

- Provide a one-page handout or a short list of vetted digital resources.

- Model brief pauses during consultations (e.g., “Let’s take one slow breath together before we review the plan.”).

- Refer interested patients to group-based MBSR or ACT programs when available. Over time, these small steps can normalize mindfulness as a standard, evidence-based component of chronic Pain Management in Healthcare.

By understanding the science, practical tools, and ethical considerations surrounding mindfulness in chronic pain, clinicians can offer patients a powerful, low-risk set of skills that enhance resilience, reduce suffering, and support a more humane, holistic approach to Pain Management and Mental Health in modern medicine.