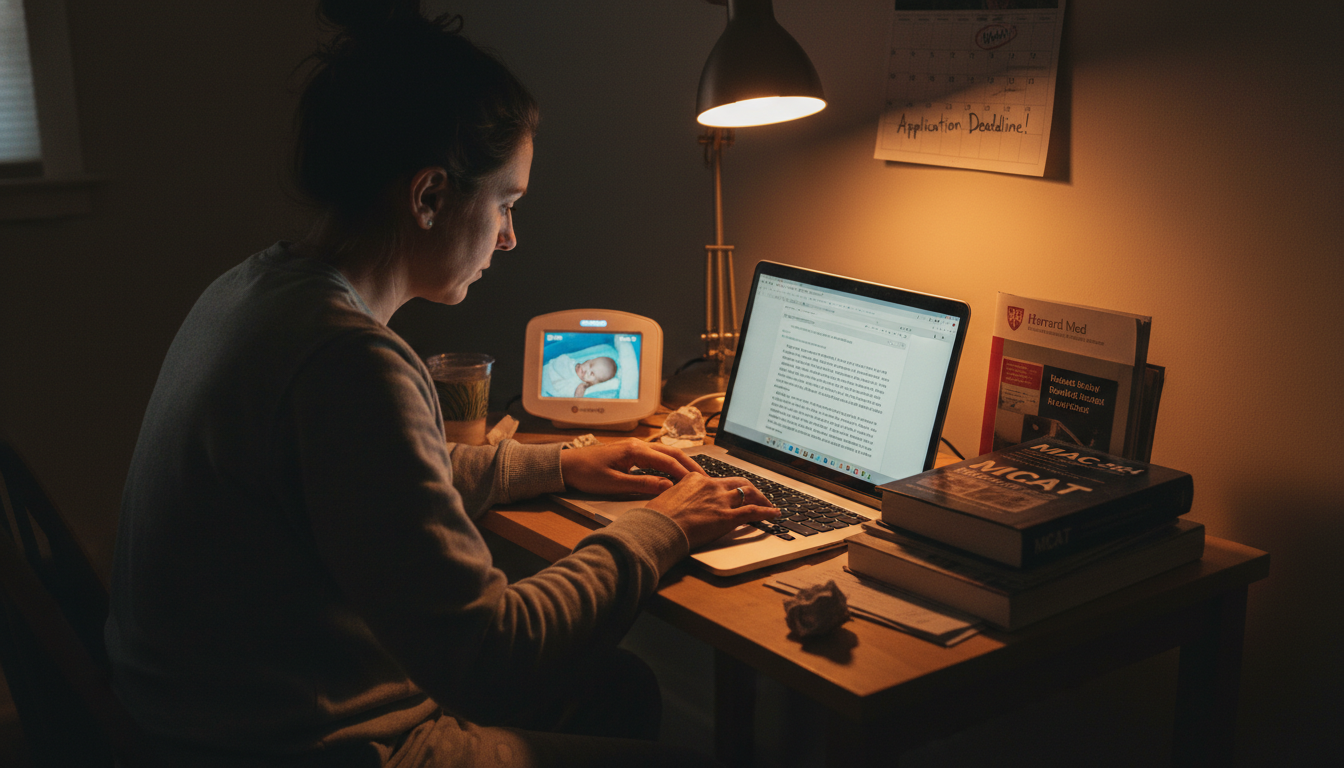

It’s 9:42 p.m. The dishwasher is finally running, the kid’s lunch for tomorrow is packed, your dad’s meds are lined up in the weekly pill box, and you’ve just sat down to work on your personal statement…for the fourth night in a row. You’re exhausted, the house is quiet, and the cursor on your screen is blinking like it’s taunting you.

You’re trying to apply to medical school while being a parent or primary caregiver. You do not have “flexible time” and “protected study hours.” You have nap windows, school pickups, therapy appointments, and middle-of-the-night fevers.

(See also: handling a criminal charge or misdemeanor for more details.)

Here’s the honest situation: you cannot apply like a traditional 20-year-old with no dependents, and you shouldn’t try. You need a different time strategy and a different framing strategy. One that doesn’t pretend you’re in the same situation as everyone else—and one that actually turns your responsibilities into strengths on the application instead of “explanations” or “apologies.”

This is how to do that.

Step 1: Accept That Your Application Timeline Is Different

You might be in one of these situations:

- You had a child in college and your grades dipped for a couple semesters.

- You’re a full-time caregiver for a parent with dementia, and your clinical hours are spotty.

- You’re working nights as a CNA and caring for two kids during the day while chipping away at prerequisites.

- You took “too many” gap years to raise your children and now worry you look “late.”

The first mental shift: your path isn’t a problem to conceal. It’s context that needs to be:

- Reflected honestly in how you manage time from now until you submit.

- Framed clearly so committees see resilience, priorities, and judgment—not chaos.

So before time management hacks, pick a realistic application cycle and timeline.

Decide: This Cycle or Next?

Ask yourself three blunt questions:

If nothing in my life changed, could I:

- Consistently study 10–15 hrs/week for the MCAT for several months?

- Put together quality essays, secondaries, and activity descriptions?

- Sustain that workload for 6–9 months without burning out or compromising caregiving safety?

Are there obvious holes:

- Zero recent clinical exposure?

- Prerequisites still in progress?

- MCAT scheduled in a month but you’re scoring 8+ points below your goal on practice exams?

If I wait one year, could I significantly improve:

- MCAT score by 4–8 points?

- GPA trend with another year of strong coursework?

- Clinical/volunteer depth in a setting that fits my caregiving life?

If your honest answers show you’re trying to cram a traditional “full-time premed” timeline into a caregiver life, adjust. Better to apply one year later with:

- A stronger MCAT

- Clear clinical experiences

- A believable story of sustained balance

…than to submit a rushed, weak application that burns money and time you do not have.

Step 2: Design a Schedule That Respects Reality

You’re not building a “study schedule.” You’re building an operational schedule for your household where studying and application work have defined, protected roles.

Map Your Non-Negotiables First

Take a blank weekly template and fill in:

- Caregiving responsibilities:

- School drop-off/pickup

- Bedtime routines

- Therapy sessions, doctor visits

- Bathing, feeding, medications

- Paid work shifts

- Commuting time

- Sleep: don’t pretend you can run on 4 hours indefinitely; pencil in 6.5–8 hours.

Now take what’s left over. That’s your true bandwidth.

Build “Micro-Block” Study Segments

You likely can’t do 4-hour study sessions regularly. So shift to micro-block thinking:

- 25–45 minute study blocks

- Anchored to existing routines:

- During nap time

- Before kids wake up (5:30–7 a.m.)

- During after-school activities (if you can be physically present but mentally studying)

- 9–11 p.m. after bedtime routines

Pick 4–6 micro-blocks per week as sacred: these are your core application hours.

For example:

- Mon/Wed/Fri 5:45–6:30 a.m. – MCAT passage practice

- Tue/Thu 8:45–10:00 p.m. – Personal statement / activities

- Sat 2:00–4:00 p.m. – Full-length review while partner/relative handles kids

That’s ~7–9 focused hours/week. Sustained over months, this is enough.

Decide “Study vs. Application” Phases

If you try to do full MCAT prep and full application writing simultaneously, while caregiving, something will break.

Split into phases when possible:

- Phase 1 (3–4 months): MCAT-focus

- 70–80% of your weekly study blocks = MCAT

- 20–30% = light journaling about experiences, keeping a log of stories, updating CV

- Phase 2 (1–2 months pre-application): Transition

- 50% MCAT (practice tests and review only)

- 50% application writing (personal statement, activities)

- Phase 3 (post-MCAT through secondaries):

- 80–90% application work

- 10–20% maintenance MCAT review (if scores not back yet or retake possible)

If you must overlap more heavily (for example, because of timing), reduce your target MCAT score a bit to something realistic for your context rather than killing yourself chasing a perfect score.

Step 3: Pick Experiences That Work With Your Life, Not Against It

A lot of parents/caregivers burn out trying to force traditional premed experiences (evening ED volunteering, research lab with rigid hours, etc.) into a life that doesn’t accommodate them.

You need clinical and non-clinical experiences that fit your constraints.

Clinical Options for Parents/Caregivers

Aim for roles that:

- Have predictable shifts

- Allow for part-time schedules

- Don’t require long commutes

Some realistic options:

- Medical assistant in a clinic with daytime hours

- Scribe with remote or flexible shifts (tele-scribing can sometimes be done from home)

- CNA positions with consistent daytime schedules

- Hospice volunteering during school hours

- Outpatient specialty clinic volunteering (oncology/primary care/women’s health) with 2–4 hr shifts mid-day

If evenings are impossible due to bedtime routines, don’t fight it. Build a story around your consistent daytime involvement in a clinical setting.

Non-Clinical and Service

You can also build meaningful service into your existing roles:

- Organizing a support group for caregivers at your local community center

- Leading a parenting class or mentorship program

- Volunteering at your child’s school health fair or vaccination clinic

- Serving at food banks during school hours or on alternating weekends

The key isn’t how “fancy” the site is. It’s whether you show:

- Consistency

- Increasing responsibility

- Insight into systems and people

Step 4: Protect Application Quality With “Minimum Viable Yes”

When your life is full, you cannot say yes to everything, and you must ruthlessly protect application quality over quantity.

Decide Your “Minimum Viable Application”

Set floor targets that you commit to hitting:

- MCAT: a score that’s competitive for your target school range, not fantasy schools you’d like in another universe

- Experiences:

- 1 solid clinical experience (≥150–300 hours)

- 1–2 service experiences (≥100–150 hours combined)

- 1–2 long-term commitments (research, job, mentoring, etc.)

- Application pieces:

- One carefully revised personal statement that clearly links caregiving to your motivation and capacities

- Activities section that highlights depth, not a random list of one-off and short stints

- Thoughtful school list tailored to your stats, missions, and geography

If something on your plate conflicts with these floors, ask whether it truly needs to continue this year.

Build a “Stop Doing” List

Example items for a premed parent:

- “I will not sign up for new short-term volunteer projects during MCAT prep.”

- “I will not entertain extra shifts at work unless it’s a financial emergency.”

- “I will not be the default planner for every extended family event during secondaries season.”

Say this explicitly to partners, family, even older children if appropriate: “This year, I’m applying to medical school. That means from March–September, I can’t take on extra roles. Here’s what that looks like.”

Step 5: Framing Your Story as a Parent or Caregiver

Now the application framing. You’ve probably heard contradictory advice:

- “Don’t sound like you’re making excuses.”

- “Highlight your caregiving; committees value that.”

- “Don’t make them worry you won’t handle med school.”

- “Show your humanity!”

You need a strategy that does three specific things:

- Explains objective data (gaps, lower GPA early on, delayed timeline) without sounding defensive.

- Converts caregiving into clearly relevant skills.

- Calms their fears about your future bandwidth.

Where to Talk About Parenting/Caregiving

Use these application parts strategically:

Personal Statement

Good for: motivation for medicine, major identity-shaping experiences, long-term caregiving roles.Work & Activities

Good for: specific caregiving roles framed as leadership, service, and complex responsibility.Secondary Essays (Challenges, Adversity, Diversity)

Good for: addressing academic dips, time gaps, and how you’ve learned to manage competing demands.Optional/Additional Info

Good for: short, factual context like “I have been the primary caregiver for my mother with advanced Parkinson’s disease since 2020; my clinical hours increased once I secured additional home support in 2023.”

How to Talk About It Without Sounding Defensive

Use a simple pattern: Context → Impact → Growth → Current Readiness

Example (for a personal statement or adversity essay):

Context:

“In my junior year, my daughter was born at 32 weeks. For several months, my days started in the NICU and ended on my dorm room floor with a statistics textbook open and my phone on the pediatrician’s speed dial.”Impact (brief, factual):

“During that year, my grades dropped and I withdrew from orgo II. I prioritized her medical appointments and early interventions slightly ahead of my coursework.”Growth:

“Navigating that period forced me to learn structured time management, ask for help, and identify what absolutely needed my attention and what did not. Over time, I rebuilt my coursework with a more realistic schedule and earned A’s in my remaining upper-division sciences.”Current Readiness:

“Now, with a stable child-care structure in place and a proven record of strong performance in rigorous courses, I approach medical training with the same deliberate planning I used to manage her early medical needs.”

They see a responsible adult who:

- Faced real constraints

- Made intentional decisions

- Recovered academically

- Has a present-day system that works

Turn Caregiving Into Skills Committees Care About

Do not just say, “Being a parent taught me responsibility.” Everyone says some version of that. Instead, show specifics that map clearly to medicine:

Longitudinal observation of health

“Managing my father’s heart failure at home exposed me to transitions of care, medication reconciliation challenges, and how communication failures between specialists and primary care can lead to harm.”Complex communication

“I learned to translate medical jargon into terms my mother understood, negotiating between her preferences and what the cardiologist recommended.”Prioritization under pressure

“Balancing night shifts, a toddler, and organic chemistry forced me to learn triage: which tasks had to happen now, which could be delegated, and which had to be dropped without guilt.”

When you describe caregiving in activities, treat it like any other significant role:

- Give it a title: “Primary caregiver for grandparent with Alzheimer’s disease”

- Provide hours per week and years

- Describe responsibilities in clinical or quasi-clinical terms when appropriate:

- Coordinated appointments

- Managed medication schedules

- Advocated within healthcare settings

- Monitored symptoms and functional status

- Highlight insights:

- Systemic barriers

- Cultural factors

- End-of-life care decisions

- Insurance/financial complexity

Step 6: Anticipate and Answer Quiet Concerns

Admissions committees may not say this out loud, but they think:

- “Can this person handle the time demands of medical school?”

- “Will parenting/caregiving pull them away from training?”

- “Is their support system solid enough?”

You need to answer those questions without sounding defensive or providing over-sharing detail.

Demonstrate Time Management With Evidence

Show, don’t promise:

- Recent academic performance while caregiving:

- Strong grades in upper-division courses after your child was born.

- Significant clinical work stacked on top of caregiving:

- “20 hours/week as a medical assistant plus 20 hours/week of child care from 2022–2024.”

- Clear upward trajectory:

- Improved GPA trend each year, especially after your caregiving responsibilities stabilized.

Speak to Support Systems Without a Full Biography

You do not need to spell out all family dynamics, but a concise line or two can be powerful in a secondary or interview:

- “My spouse and I have arranged reliable child care coverage for standard work hours, and we have a local extended family support network.”

- “My siblings and I now share caregiving duties for my mother through a rotating schedule, which has allowed me to increase my clinical hours and will allow full-time commitment to medical training.”

You’re sending one clear signal: “I take this seriously and I have an actual plan.”

Step 7: Surviving Secondaries and Interview Season as a Caregiver

Two of the most chaotic phases during the application year are:

- The secondary essay flood.

- Travel and scheduling for interviews (or long virtual days).

You need a tactical plan before that chaos hits.

Secondaries: Pre-Write and Pre-Allocate

- Start collecting secondary prompts for your target schools months in advance. Student Doctor Network, Reddit, or school-specific websites typically have last year’s prompts.

- Pre-write thoughtful drafts for:

- “Why our school?”

- Adversity/challenge essays

- Diversity essays

- Service/mission fit prompts

Then schedule “secondary weeks”:

- Example: Reserve 2–3 hours on Sat/Sun for 4–6 weeks during peak season.

- Have canned childcare solutions: partner covers, paid backup sitter, or grandparents on standby during that period if possible.

Decide upfront:

- How many schools you realistically can handle secondaries for within 2 weeks of receiving them. If caregiving/time is intense, that might be 15–20, not 35.

Better to answer 15 secondaries well than send 35 rushed, generic essays.

Interviews: Plan Coverage and Communication

For in-person or virtual interviews:

- Tell your partner/family as soon as you get an invite. Don’t wait to see if you can “handle it alone.”

- If arranging daycare or respite care, think of interviews as “medical appointments” that can come up with 2–3 weeks notice.

- For virtual interviews:

- Plan quiet zones: library study rooms, borrowed office, or a friend’s apartment during the workday.

- Have a backup internet option (phone hotspot), especially if your home environment is unpredictable.

In interviews, when parenting/caregiving comes up, keep your answer:

- Confident

- Specific

- Future-facing

Example:

“My daughter is five now and in full-time school, and my partner has structured work hours. We’ve planned for medical school for the past two years, including backup child care options, so that I can commit fully to training.”

You are not apologizing. You are describing an adult plan.

Step 8: When Things Go Off the Rails (Because Sometimes They Will)

There will be weeks when:

- A child is sick all night.

- Your parent is hospitalized.

- Daycare closes.

- You miss a practice exam or an application deadline.

The solution is not to “just push harder.” It’s to have a protocol for disruption.

Build a Disruption Protocol

Write this out somewhere:

What are my absolute priorities this week?

(For example: my child’s health, my upcoming MCAT, my job I cannot lose.)What can be paused without permanent damage?

- One volunteering shift?

- A non-essential social commitment?

- A non-urgent secondary essay for a low-priority school?

How will I adjust my application plan?

- Move the MCAT back one date?

- Email the volunteer coordinator about a temporary pause?

- Drop one or two schools from my list to reduce secondary volume?

Who can I ask for help from, specifically?

- Partner covers bedtime for 2 nights.

- Sibling handles one week of parent visits.

- Friend swaps school pickup duties.

Practice this once or twice before real crises hit. Review your schedule on Sunday nights and ask: “If this week collapsed, what would I protect?”

Key Takeaways

You cannot—and should not—apply like someone without caregiving responsibilities. Build a realistic, micro-blocked schedule that respects your actual life and focuses on a minimum viable quality application, not maximum quantity.

Frame your parenting or caregiving as a source of concrete skills and insight, not an excuse. Use clear patterns: context, impact, growth, and present readiness. Show that you’ve already succeeded academically and clinically while caregiving.

Anticipate the application’s high-pressure phases—MCAT prep, secondaries, interviews—and pre-plan child care, backup support, and realistic school lists. Your goal is not to show that you do everything alone; it’s to show you understand your limits and have a sustainable plan for medical training.