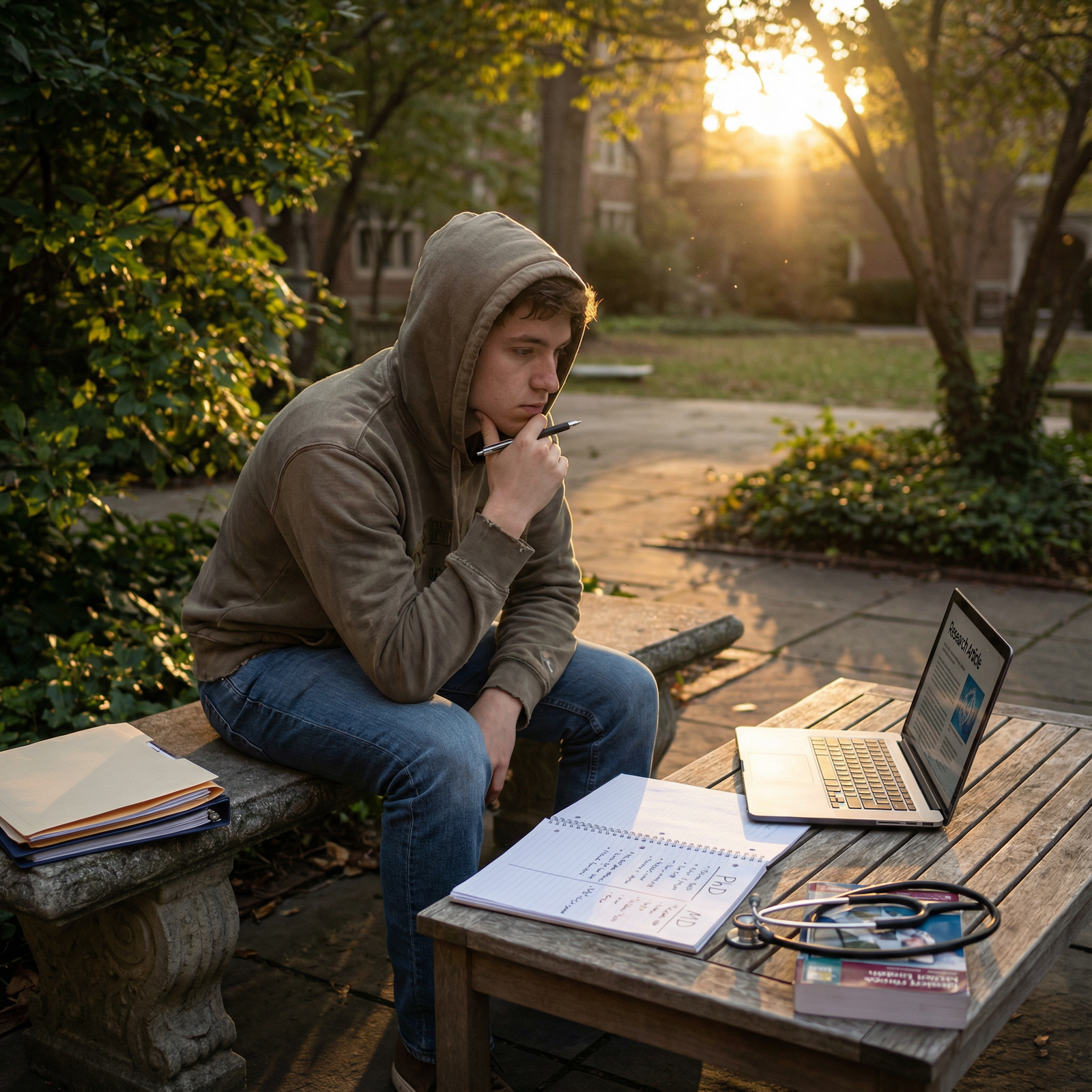

When you’re passionate about healthcare or the life sciences, one of the most important career decisions you’ll make is whether to pursue a PhD or an MD. Both are prestigious, both are demanding, and both can position you to impact patient care and scientific discovery—but in very different ways.

This guide breaks down the PhD vs. MD choice in practical, residency-applicant–friendly terms: training structure, lifestyle, funding, salary, and long‑term career outcomes in healthcare careers and life sciences. The goal is not to tell you which path is “better,” but to help you make a confident, informed career decision that fits who you are and the work you want to do.

Understanding the Foundations: What a PhD and MD Really Mean

What Is a PhD in the Life Sciences?

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) is a research doctorate that prepares you to generate new knowledge. In the life sciences and health-related fields, that often means advancing our understanding of disease mechanisms, developing new diagnostics or therapies, or improving healthcare delivery and policy.

Typical duration: 3–7 years, depending on country, field, and project progress.

Common life science PhD fields include:

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Biochemistry

- Pharmacology

- Immunology

- Neuroscience

- Epidemiology and Public Health

- Biomedical Engineering

- Health Policy and Outcomes Research

Core Features of Life Science PhD Programs

Research-Centered Training

Your primary job is to answer a novel scientific question. You’ll design experiments, collect data, analyze results, and interpret what they mean for your field.Original Dissertation

You must complete and defend a dissertation based on your original research. This is the main requirement for earning the degree.Mentored Apprenticeship Model

You work closely with a principal investigator (PI) and research group. Your training is highly shaped by your advisor’s mentorship, lab culture, and funding stability.Funding & Stipend

Many life science PhD programs in the U.S. and Europe provide tuition waivers and a modest stipend in exchange for your research and/or teaching. You are paid like a trainee employee rather than paying tuition out of pocket.Typical Settings

- Universities and medical schools

- Research institutes (e.g., NIH intramural programs, Max Planck Institutes)

- Joint university–industry or engineering programs

Who Thrives in a PhD?

A PhD is usually a better fit if you:

- Feel energized by open-ended questions and uncertainty

- Enjoy deep focus, technical work, and troubleshooting in the lab or at a computer

- Care about contributing to knowledge more than being on the clinical front line

- Are comfortable with delayed, less predictable financial payoff

- Want flexibility to work in academia, industry, policy, or data science

What Is an MD?

A Doctor of Medicine (MD) is a professional doctorate that prepares you to diagnose, treat, and prevent disease in patients. The training is built around clinical reasoning, communication, and hands-on patient care in real-world healthcare systems.

Typical duration:

- 4 years of medical school, then

- 3–7+ years of residency, plus optional fellowship (1–3 years) for subspecialization.

Core Features of MD Programs

Clinical Focus

The central question is: “How do I take care of this person in front of me?” You learn to gather histories, perform physical exams, interpret tests, and make treatment decisions.Structured Curriculum

- Pre-clinical years: Foundational sciences (anatomy, physiology, pathology, pharmacology) plus early clinical exposure.

- Clinical years: Core clerkships in internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, OB/GYN, psychiatry, family medicine, and more.

Residency Training

After graduation, you match into a specialty (e.g., internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, emergency medicine). Residency is an intensive apprenticeship in delivering safe, effective patient care while gradually assuming responsibility.Licensure & Board Exams

MDs must pass high-stakes exams (e.g., USMLE/COMLEX in the U.S., MCCQE in Canada) and meet training requirements to obtain full practice licensure.Tuition & Debt

In many countries (especially the U.S.), medical students pay substantial tuition and often graduate with significant educational debt, later offset by higher earning potential as attending physicians.

Who Thrives in an MD?

An MD is usually a better fit if you:

- Want to interact with patients daily and impact individuals directly

- Like fast-paced, team-based environments (clinics, hospitals, ORs)

- Are comfortable with high-stakes decisions and acute crises

- Value a clearer financial trajectory and higher long-term earning potential

- Are prepared for long hours and less flexibility during training

Training, Structure, and Daily Life: PhD vs. MD

Program Structure and Duration

| Aspect | PhD in Life Sciences | MD (Medicine) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Duration | 3–7 years (typical) | 4 years med school + 3–7 years residency (+ fellowship) |

| Primary Focus | Research and theory | Clinical practice, diagnosis, and patient care |

| Core Activities | Experiments, data analysis, writing papers | History/physical exams, procedures, decision-making |

| Final Requirement | Dissertation and defense | Clinical rotations, licensing exams, completion of residency |

| Clinical Exposure | Limited (unless clinical or translational PhD) | Extensive (clerkships, residency, on-call responsibilities) |

PhD training is relatively unstructured compared to medical school. You have milestones (coursework, qualifying exams, proposal, dissertation), but your day-to-day schedule is self-managed, shaped by your experiments, meetings, and deadlines.

MD training is highly structured and standardized, especially in the clinical years and residency. Your schedule, rotations, call shifts, and educational activities are tightly regulated.

Skills You Develop in Each Path

Skill Set of a PhD Graduate

By the time you finish a PhD, you typically have:

Advanced Research Methodology Skills

Designing experiments, choosing appropriate controls, managing variables, and using techniques specific to your field (e.g., CRISPR, imaging, bioinformatics).Quantitative and Analytical Strength

Statistical analysis, coding (R, Python, Matlab), bioinformatics, or big‑data analysis depending on your project.Scientific Writing and Communication

Writing manuscripts, grants, and reviews; presenting at conferences; teaching undergraduates or mentoring junior trainees.Project and Time Management

Coordinating complex research projects with long timelines and multiple collaborators while managing setbacks and failed experiments.Resilience and Problem-Solving

Handling rejected papers, failed experiments, and funding uncertainties while learning to pivot and refine hypotheses.

These skills translate well beyond academia—to biotech, pharma, consulting, health tech, public health, and policy roles.

Skill Set of an MD Physician

By the end of residency, MDs typically excel in:

Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making

Integrating history, physical exam, labs, and imaging to reach diagnoses and management plans, often under time pressure.Interpersonal and Communication Skills

Breaking bad news, discussing prognosis, shared decision-making, and coordinating with other healthcare professionals.Procedural Skills

Depending on specialty, performing everything from suturing and lumbar punctures to colonoscopies, catheterizations, or major operations.Crisis Management and Prioritization

Recognizing and managing acutely ill patients, triaging competing demands in the ED, ward, or ICU.Systems-Based Practice

Navigating insurance, hospital policies, multidisciplinary teams, and quality improvement initiatives.

These competencies are central to clinical healthcare careers, but also transfer to leadership, administration, public health, and health systems innovation.

Career Outcomes: Where Do PhDs and MDs Actually Work?

Typical Career Paths for PhD Holders in Health and Life Sciences

Academic Researcher / Professor

- Conducts independent research, secures grants, teaches medical or graduate students, mentors trainees.

- Can be based in a medical school, basic science department, or research institute.

- Career trajectory: postdoc → assistant professor → associate professor → full professor.

Biotech or Pharmaceutical Scientist

- Works on drug discovery, target validation, clinical biomarkers, or translational research.

- Often more structured hours and higher starting salaries than academia, but less academic freedom.

Clinical or Translational Research Scientist

- Bridges lab science and patient care (e.g., biomarker development, clinical trial design).

- May collaborate closely with MDs and hospitals.

Data Scientist / Bioinformatician

- Uses computational and statistical methods to interpret large biomedical datasets.

- In demand across healthcare tech companies, insurance, and health systems.

Policy, Regulatory, and Consulting Roles

- Works for government agencies (e.g., FDA, CDC, EMA), NGOs, or consulting firms.

- Applies scientific training to health policy, regulation, or strategy.

Science Communication and Education

- Medical writing, scientific journalism, curriculum development, or educational technology.

The common thread: PhD careers are diverse and less linear than MD careers. There is more flexibility to move across sectors but also more variability and uncertainty in trajectories, especially in academia.

Typical Career Paths for MD Physicians

Direct Clinical Practice (Most Common)

- Primary care (family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics)

- Hospital-based specialties (hospitalist, emergency medicine, critical care)

- Surgical specialties (general surgery, orthopedics, neurosurgery, etc.)

- Non-surgical specialties (cardiology, oncology, anesthesiology, radiology, psychiatry)

Academic Medicine

- Combines patient care with teaching and research.

- May run clinical trials, quality improvement projects, or health services research.

Healthcare Administration and Leadership

- Medical director, chief medical officer, hospital or system leadership roles.

- Focus on quality, safety, and strategic planning of healthcare delivery.

Public Health and Policy

- Roles in CDC, WHO, ministries of health, or NGOs.

- Work on population health, outbreak response, health systems strengthening.

Industry and Consulting

- Pharmaceutical and device companies (medical affairs, safety, clinical development).

- Consulting firms focusing on healthcare strategy and operations.

MD careers are often clinically anchored: even if you move into administration or industry, your identity and credibility are grounded in clinical training and experience.

Money, Time, and Lifestyle: Practical Considerations

Financial Landscape: Tuition, Debt, and Salary

Cost of Training

PhD

- Typically: Tuition covered + stipend (especially in STEM/life sciences).

- Stipends range widely (e.g., ~$25,000–$45,000 USD/year in many U.S. programs), often modest for the local cost of living.

- You may graduate with minimal or no additional educational debt, especially if you avoid new consumer debt.

MD

- In many countries, especially the U.S., medical school tuition is high.

- Graduates frequently carry six-figure educational debt.

- Some countries (e.g., many in Europe) have lower or no tuition, but opportunity costs and training intensity still matter.

Earning Potential

Approximate U.S. salary ranges (these are broad estimates, vary by region, sector, and years of experience):

PhD Holders

- Postdoctoral fellow: $55,000–$75,000

- Industry research scientist: $100,000–$160,000

- Academic faculty (tenure-track):

- Assistant professor: $80,000–$150,000

- Full professor (successful, with grants): $150,000–$250,000+

MD Holders

- Resident physician: $60,000–$80,000 (with heavy hours)

- Attending primary care physician: $200,000–$280,000+

- Subspecialist (e.g., cardiology, GI, orthopedics): $300,000–$600,000+, sometimes higher in procedure-intensive specialties.

The MD route usually leads to higher lifetime earnings, but with far more upfront cost, delayed income, and debt. A PhD often offers earlier financial independence (no tuition, earlier stipend) but generally lower ceilings in pure academic tracks.

Work–Life Balance and Lifestyle

During Training

PhD

- Hours can be long (50–70/week), but often with more control: you decide when to run experiments or analyze data.

- Deadlines spike around conferences, paper submissions, and thesis defense.

- Weekends and evenings may be needed for time-sensitive experiments, but overnight call is rare.

MD (Medical School and Residency)

- Pre-clinical years: More predictable but intense study volumes.

- Clinical years and residency:

- Long shifts (often 60–80+ hours/week), nights, weekends, and holidays.

- Less control over schedule; must be present for patient care and team coverage.

- Sleep disruption, emotional intensity, and burnout risk are real considerations.

After Training

PhD Graduates

- Work-life balance varies by sector:

- Industry: often more predictable hours than academia.

- Academia: can be demanding due to grant pressures, but schedules are usually flexible day to day.

- Work-life balance varies by sector:

MD Physicians

- Highly variable by specialty and practice model:

- Some outpatient specialties (e.g., dermatology, certain primary care roles) can offer very good balance.

- Hospital-based and surgical specialties may have more nights, weekends, and call.

- More flexibility later in career to adjust FTE, join group practices, or move to telemedicine/locum roles.

- Highly variable by specialty and practice model:

How to Choose: Aligning PhD vs. MD with Your Goals and Personality

Key Questions to Ask Yourself

Do you want your primary impact to be on individual patients or on systems and knowledge?

- Individual, face-to-face: more MD-aligned.

- Systems, mechanisms, and broad-scale change: often more PhD-aligned.

Which type of uncertainty motivates you more?

- Clinical uncertainty (what diagnosis/therapy is right now for this patient)

- Scientific uncertainty (what does this pathway/protein/dataset really mean?)

What kind of day-to-day activities sound most energizing long term?

- PhD: pipetting, coding, reading papers, writing, analysis, designing experiments.

- MD: talking with patients, doing procedures, collaborating with teams, managing crises.

How do you feel about financial sacrifice and timing?

- Are you willing to accept earlier but lower income (PhD) vs. delayed but higher earnings with debt (MD)?

Can you handle delayed gratification and long projects?

- PhD research often has slow feedback loops.

- Clinical care provides faster feedback: you see immediate impact of decisions.

Real-World Illustrations

Dr. Jane Smith, MD – Pediatrician

Jane chose an MD because she loved working with children and families. During residency, her schedule was grueling—long calls, night shifts, emotionally tough cases. Today, she works in a group pediatric practice, enjoys seeing her patients grow up, and maintains a predictable workweek with shared call. She occasionally collaborates on clinical research projects but remains primarily a clinician.Dr. John Doe, PhD – Cancer Genetics Researcher

John pursued a PhD in molecular biology after realizing he was more fascinated by mechanisms than direct care. His days are filled with lab meetings, experimental design, and data analysis. Grants are competitive and publication timelines can be long, but he finds deep satisfaction in advancing knowledge that may underpin future therapies. He collaborates closely with oncologists in a translational research program.

Neither path is “easier”—they are hard in different ways. Your fit depends on where you derive meaning, how you handle stress, and what kinds of problems you want to solve.

What About Combined MD/PhD Programs?

Combined MD/PhD (or similar dual-degree) programs are designed for those who want to be physician-scientists—people who both see patients and run substantial research programs.

- Duration: Typically 7–9 years total (integrated).

- Funding: Many programs (e.g., MSTP in the U.S.) provide tuition remission and a stipend, reducing debt burden.

- Career Outcomes: Faculty positions at academic medical centers, leading translational research, clinical trials, or health services research while practicing clinically.

MD/PhD is not the best path just to “keep options open”—it is a long, demanding commitment best suited for those who are genuinely passionate about doing both research and patient care at a high level.

FAQs: Common Questions About PhD vs. MD for Healthcare Careers

1. Can I pursue both a PhD and an MD, and is it worth it?

Yes. MD/PhD programs and sequential training (doing one degree after the other) are both possible.

- It may be worth it if you:

- Feel strongly committed to clinical practice and high-level research

- Envision a career in academic medicine leading a lab, running trials, or shaping translational science

- It may not be worth it if you:

- Mainly want to practice clinically (most MDs can participate in clinical research without a PhD)

- Mainly want to be a full-time scientist (you generally don’t need an MD to do high-quality lab or data science research)

The added years of training (often 3–5 extra) should be justified by a clear long-term career vision as a physician-scientist.

2. Which is harder to get into: PhD or MD?

It depends on country, institution, and field, but generally:

- MD admissions (especially in the U.S.) are often more competitive on traditional academic metrics (GPA, MCAT, overall acceptance rate).

- PhD admissions may be more variable and field-specific; strong research experience, letters from PIs, and fit with potential advisors are crucial.

Think less about “which is harder” and more about “which is a better fit for my interests and strengths,” then build a targeted application profile accordingly.

3. Can PhD holders work in clinical settings or directly with patients?

Generally, PhD holders without a medical license cannot independently practice medicine or prescribe treatments, but they can:

- Conduct clinical or translational research in hospitals and clinics

- Serve as clinical trial coordinators, biostatisticians, or outcomes researchers

- Work in psychology or allied health (with additional licensure in some countries, e.g., clinical psychology PhD)

- Contribute to patient education materials, guidelines, and policy

If your primary goal is direct patient care, you typically need an MD (or DO, or another clinical degree like PA, NP, PT, etc., depending on scope).

4. Is a PhD “worth it” if I don’t want to stay in academia?

Yes, a PhD can absolutely be “worth it” outside academia—but value depends on clarity of goals and skill development:

- Many PhDs build satisfying careers in biotech, pharma, consulting, government, data science, and health tech.

- During training, deliberately cultivate transferable skills (coding, statistics, project management, communication) and seek internships or collaborations beyond your PI’s lab.

- Be realistic about the job market: tenure-track roles are limited, but industry and alternative research careers are robust for candidates with strong skills and adaptability.

5. If I’m still undecided, what should I do during undergrad or early medical school?

Use your remaining time to test both worlds in low-risk ways:

- Shadow clinicians in different specialties to see real clinical practice.

- Join a research lab (ideally in a medical or life sciences department) and stay long enough to experience the realities of research (not just the exciting parts).

- Take electives in public health, biostats, or health policy to see if you enjoy quantitative population-level thinking.

- Talk to residents, attending physicians, PhD students, postdocs, and physician-scientists about their day-to-day realities and career satisfaction.

- Reflect honestly on whether your best days are spent with people in clinical settings or with data/experiments/ideas.

Document your experiences in a journal or note app. Patterns will emerge over time that can clarify your career decision.

By understanding how PhD and MD paths differ in training, lifestyle, and long-term opportunities, you position yourself to choose a route that aligns with your strengths and values—whether that means treating patients at the bedside, pushing the frontiers of biomedical knowledge, or ultimately blending both as a physician-scientist.

Whichever path you choose, intentional exploration and honest self-assessment now will pay dividends throughout your career in healthcare and the life sciences.