Introduction: Understanding Medical School Prerequisites and How to Plan for Them

The path to Medical School starts years before you submit your primary application. What you choose to study, how you spend your time outside the classroom, and the way you prepare for the MCAT all determine whether you are a competitive applicant.

Medical School prerequisites are more than just boxes to check. They are designed to ensure you have the scientific foundation, academic discipline, and real-world insight needed to succeed in a demanding medical curriculum and, ultimately, in clinical practice.

This guide breaks down the top 10 prerequisites for Medical School—including coursework, MCAT Preparation, Clinical Experience, and key Application Tips—so you can plan your premed and Medical School preparation strategically. Whether you’re early in college or preparing to apply this cycle, you’ll find concrete steps and examples to help you build a strong, cohesive application.

1. Building a Strong Academic Foundation for Medical School

A strong academic record is one of the most visible indicators that you can handle the rigor of Medical School. Admissions committees carefully review your GPA trends, course difficulty, and performance in core science classes.

Target GPA and Academic Competitiveness

While there is no universal cutoff, many allopathic (MD) schools view a 3.5+ overall GPA and 3.5+ science GPA (BCPM: Biology, Chemistry, Physics, Math) as competitive. Osteopathic (DO) schools may have slightly more flexibility, but the trend is similar: higher is better, and upward grade trends are valued.

If your GPA is lower:

- Prioritize recent, sustained academic improvement, especially in upper-level sciences.

- Consider taking additional post-bacc or upper-division coursework to demonstrate readiness.

- Avoid overloading with too many difficult courses in one semester if it risks your GPA.

Key Academic Areas to Strengthen

A strong premed academic profile typically includes:

- Natural Sciences

- General Biology (with labs)

- General and Organic Chemistry (with labs)

- Physics (with labs)

- Mathematics

- Statistics is increasingly important, especially for evidence-based medicine and research.

- Some schools still appreciate or require Calculus.

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Psychology, Sociology, Ethics, Philosophy, and Communication courses help develop critical thinking and understanding of patient behavior and social determinants of health.

Strategic Course Planning

- Balance challenging science courses with GPA-protecting electives that you genuinely enjoy.

- Avoid withdrawing repeatedly or frequently changing majors without a clear narrative—admissions committees may question your consistency.

- Use academic advising and premed advisors early to help map out prerequisites and avoid scheduling conflicts.

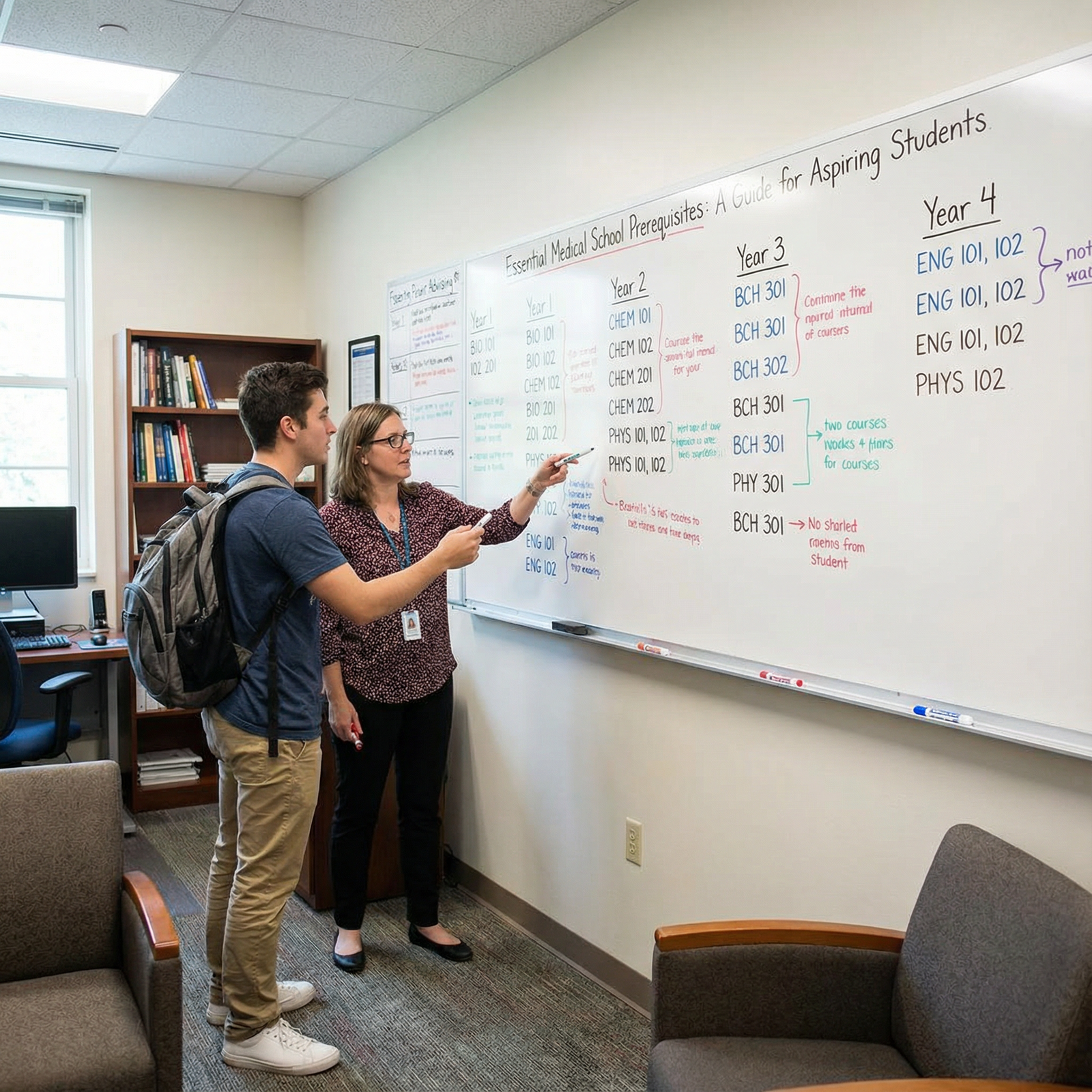

2. Meeting Formal Prerequisite Coursework Requirements

Every Medical School sets its own prerequisite rules, but most share a common core of required or strongly recommended courses. Understanding and planning for these early in your undergraduate career is essential.

Common Required or Recommended Premed Courses

Typical prerequisites for Medical School include:

Biology (with lab)

Usually 2 semesters of introductory biology with labs.- Topics: cell biology, genetics, evolution, physiology, ecology.

- Consider upper-level biology (e.g., physiology, microbiology) for added depth.

General (Inorganic) Chemistry (with lab)

Typically 2 semesters with labs.- Foundation for Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry.

Organic Chemistry (with lab)

Often 2 semesters, though some schools accept 1 semester plus Biochemistry.- Fundamental for understanding molecular interactions, drugs, and metabolism.

Physics (with lab)

Usually 1 full year (2 semesters).- Either algebra-based or calculus-based, depending on your major and school.

Biochemistry

Increasingly a required course rather than just recommended.- Often a single semester; crucial for MCAT and Medical School curricula.

English / Writing-Intensive Courses

Typically 1–2 semesters focusing on writing, analysis, and communication.- Demonstrates your ability to communicate clearly—critical in clinical practice.

Some schools may also require or strongly recommend:

- Psychology and Sociology (aligned with MCAT content)

- Statistics or Biostatistics

- Genetics, Anatomy, or Physiology

- Humanities or ethics courses (medical humanities, bioethics)

How to Verify School-Specific Requirements

Because requirements vary, you should:

- Check each Medical School’s admissions website.

- Use centralized resources (e.g., MSAR for MD schools, Choose DO Explorer for DO schools).

- Plan at least 1–2 years ahead to fit all courses in before you apply.

Course Selection and Load Management

- Avoid clustering Physics, Organic Chemistry, and Biochemistry all in one semester if possible.

- Consider taking one of your tougher prerequisites in the summer if it helps you focus—just ensure the institution is accredited and accepted by your target schools.

- If you are a non-traditional student or career-changer, a formal post-bacc program can help structure your prerequisites.

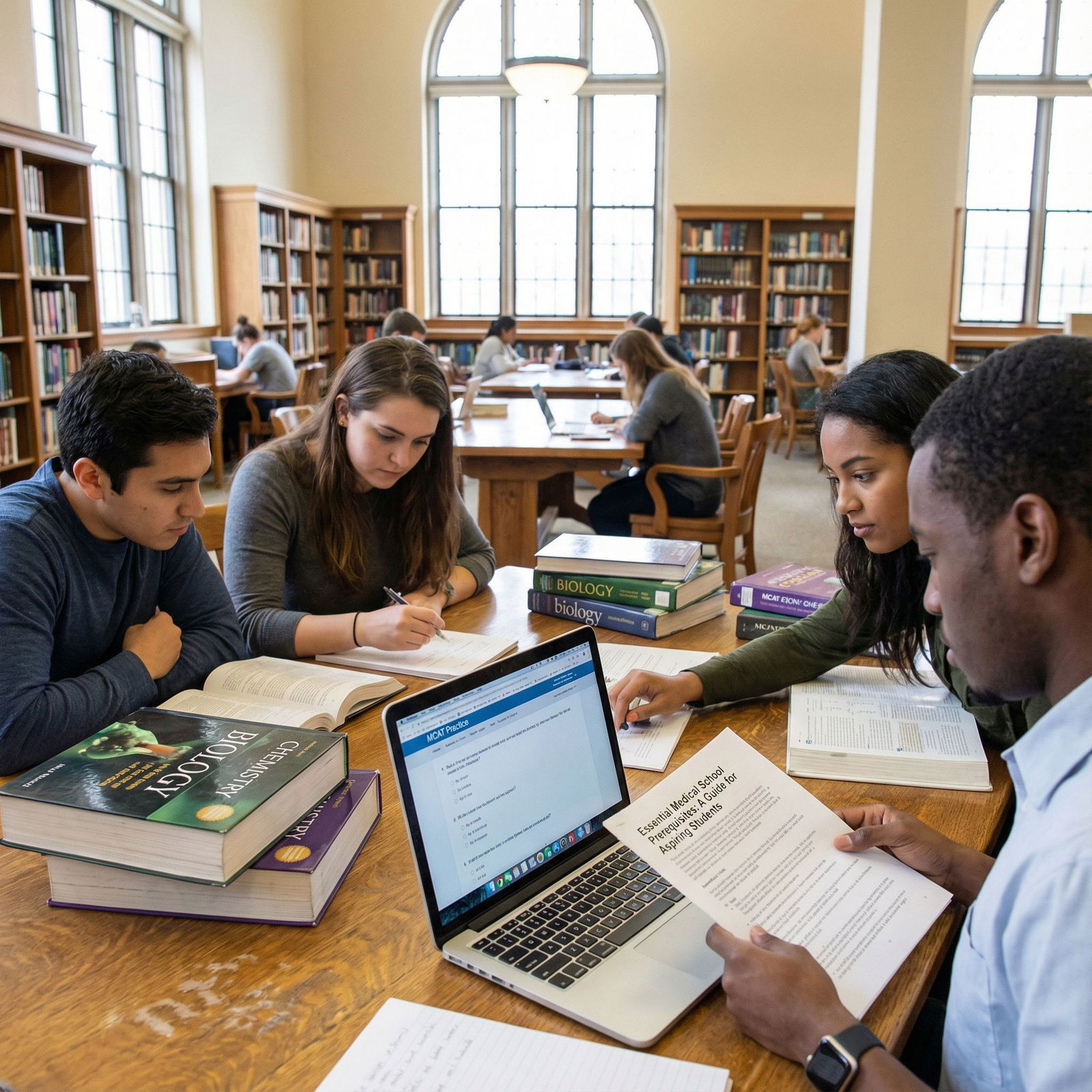

3. MCAT Preparation: Strategy, Timing, and Score Goals

The Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) is a critical standardized exam that assesses your readiness for Medical School. It covers scientific knowledge, reasoning, and understanding of psychological and social contexts of health.

MCAT Structure and Content

The MCAT is divided into four sections:

- Chemical and Physical Foundations of Biological Systems (Chem/Phys)

- Critical Analysis and Reasoning Skills (CARS)

- Biological and Biochemical Foundations of Living Systems (Bio/Biochem)

- Psychological, Social, and Biological Foundations of Behavior (Psych/Soc)

Scoring ranges from 472–528, with 500 as the center. Many competitive MD programs see successful applicants with 510+, while DO schools often accept a slightly wider range, though higher is still advantageous.

When to Take the MCAT

- Take the MCAT only when fully prepared, ideally after completing:

- General Biology, General Chemistry, Organic Chemistry, Physics, and Biochemistry.

- At least introductory Psychology and Sociology recommended.

- Aim for an exam date that allows you to receive your score before submitting or finalizing your school list (e.g., test by April–May for the June–July application submission period).

Effective MCAT Preparation Strategies

- Timeline:

- Most students study for 3–6 months, 10–25 hours per week, depending on schedule and baseline.

- Study Resources:

- Official AAMC materials (practice exams, question packs).

- Comprehensive MCAT prep books or online courses.

- Question banks and full-length practice exams.

- Approach:

- Start with a diagnostic test to identify strengths and weaknesses.

- Build a study schedule with specific daily or weekly goals.

- Incorporate active learning (flashcards, practice questions) rather than only reading.

- Take multiple full-length practice exams under realistic testing conditions.

Retaking the MCAT

If your score is below your target:

- Reflect honestly: was it content gaps, testing strategies, or test anxiety?

- Wait to retake only when you have a significantly improved plan and enough study time.

- Multiple attempts are allowed, but each score remains visible, so having a clear improvement strategy is essential.

4. Gaining Meaningful Clinical Experience

Clinical Experience is one of the most important Medical School prerequisites that cannot be replaced by coursework alone. It demonstrates that you understand the realities of patient care and confirms your commitment to a career in medicine.

Types of Valuable Clinical Experiences

Hospital or Clinic Volunteering

- Roles may include assisting at the front desk, escorting patients, helping with non-clinical tasks.

- Shows long-term engagement and commitment to patient-centered environments.

Physician Shadowing

- Observing physicians in various specialties (e.g., primary care, surgery, pediatrics).

- Focus on active observation—note how physicians communicate, manage time, discuss risks and benefits.

Clinical Employment

- Roles such as scribe, medical assistant, EMT, CNA, or phlebotomist.

- Provides deeper, hands-on exposure and often richer examples for your personal statement and interviews.

Hospice, Nursing Home, or Community Health Center Work

- Highlights compassion, cultural competence, and interest in underserved populations.

How Much Clinical Experience Is Enough?

There is no fixed number, but many successful applicants accumulate:

- At least 100–150 hours of direct clinical exposure as a minimum.

- More competitive candidates frequently have several hundred hours, especially if gained consistently over time.

Quality and reflection matter more than sheer quantity:

- Be able to articulate what you learned, how it impacted your view of medicine, and how it shaped your future goals.

- Diversity of settings (e.g., inpatient, outpatient, rural/urban) can be an asset.

Making the Most of Your Clinical Experience

- Keep a journal after shifts: key moments, patient interactions, ethical dilemmas, and personal reactions.

- Ask supervisors for ongoing feedback and, eventually, letters of recommendation if appropriate.

- Use these experiences to test your motivation—do you still want to be a physician after seeing the challenges?

5. Research Experience and Scientific Inquiry

While research is not mandatory for every Medical School, it has become an important component of a competitive application, especially for academic or research-intensive programs.

Why Research Matters for Premeds

- Demonstrates your ability to think critically, analyze data, and handle complex problems.

- Shows comfort with the scientific method, hypothesis testing, and evidence-based reasoning.

- For students interested in MD/PhD or academic medicine, it is essential.

Types of Research for Premeds

- Basic Science Research

- Laboratory-based projects in biology, chemistry, neuroscience, etc.

- Clinical Research

- Involves patient data, clinical trials, chart reviews, or outcomes studies.

- Public Health or Social Science Research

- Examines population health, disparities, health policy, or behavioral health.

Getting Involved in Research

- Approach professors after class or email faculty whose work interests you.

- Join structured summer research programs (e.g., SURF, NIH programs).

- Ask to start with smaller tasks (data entry, literature review) and work up to larger responsibilities.

Strengthening Your Research Profile

- Aim to stay with a project for at least 6–12 months if possible.

- Seek opportunities to:

- Present at poster sessions or conferences.

- Co-author publications, if available.

- Reflect on what you learned about the research process and its impact on patient care.

6. Letters of Recommendation: Choosing and Cultivating Strong Advocates

Letters of Recommendation (LORs) give admissions committees an external, professional view of your character, work ethic, and academic potential.

Typical Letter Requirements

Many Medical Schools request:

- 2 science faculty letters (e.g., Biology, Chemistry, Physics, or Math).

- 1 non-science letter (e.g., Humanities, Social Sciences, or a mentor).

- Optional or additional:

- A letter from a physician you have shadowed.

- A letter from a research supervisor or principal investigator (PI).

Some schools accept or prefer a committee letter from your undergraduate institution’s pre-health committee instead of multiple individual letters.

How to Choose Recommenders

Ideal recommenders:

- Know you well over time (not just from one semester).

- Can comment specifically on your intellectual curiosity, reliability, communication, and professionalism.

- Have seen you in challenging situations (e.g., advanced courses, research, leadership roles).

Tips for Securing Strong Letters

- Build relationships early: attend office hours, participate in class, ask questions.

- Approach potential writers 2–3 months in advance of your deadlines.

- Provide:

- Your CV or resume

- Draft of your personal statement

- List of schools and their requirements

- Bullet points of key qualities or experiences you hope they’ll highlight

- Politely ask if they can write a “strong, positive letter of recommendation”—this gives them an opening to decline if they cannot.

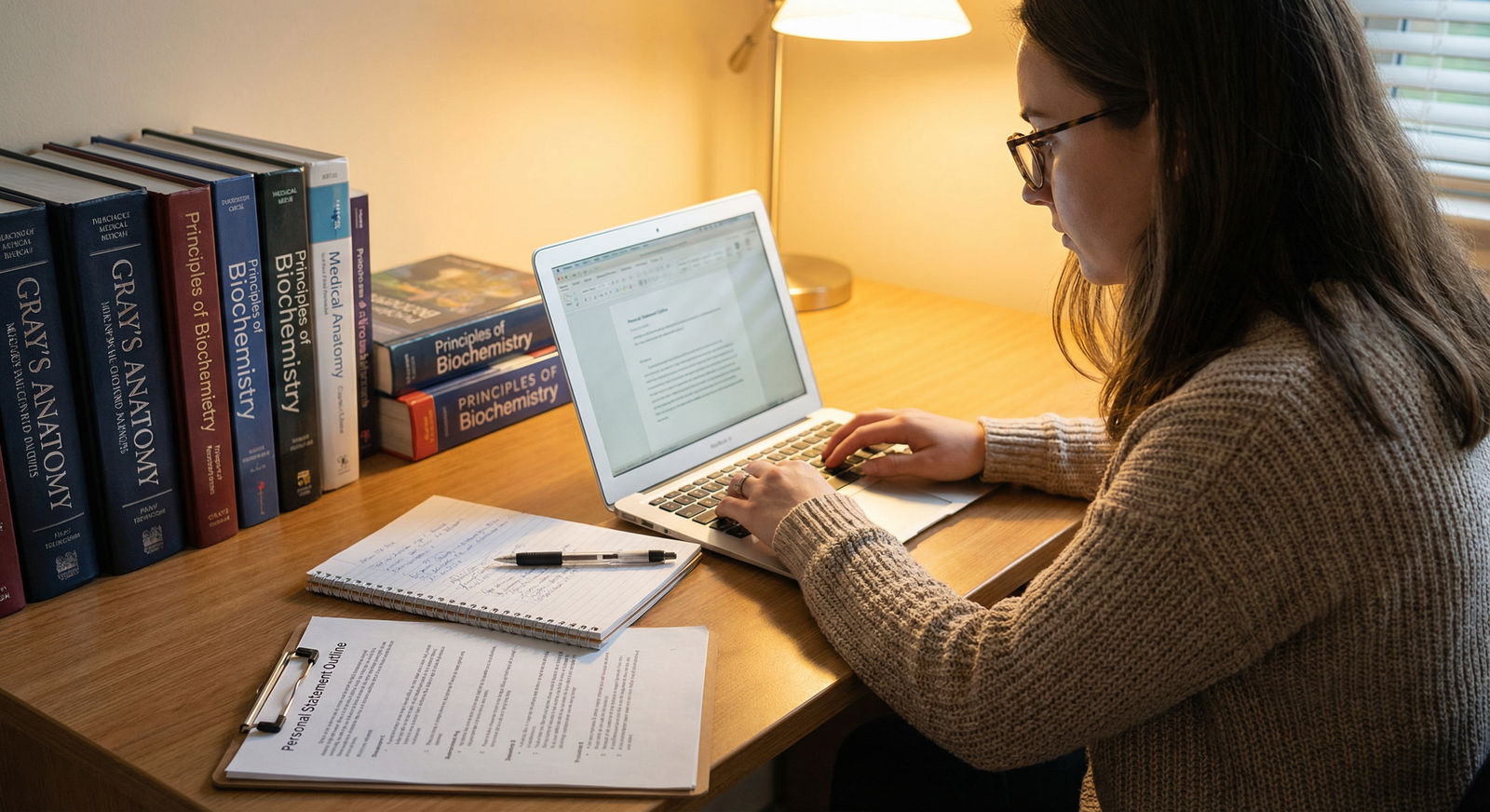

7. Crafting a Compelling Personal Statement and Written Application

Beyond grades and scores, admissions committees want to understand who you are and why you want to become a physician. Your personal statement and written experiences are crucial for conveying this.

Purpose of the Personal Statement

Your personal statement should:

- Explain why medicine, not just why science or helping people.

- Highlight key experiences that shaped your decision (clinical, personal, academic, or service).

- Showcase reflection, maturity, and insight into what a medical career entails.

Strategies for a Strong Personal Statement

- Start early—brainstorm months in advance of your application.

- Focus on specific stories, not a list of accomplishments.

- Show growth over time: how you responded to challenges, what you learned.

- Keep language clear, concise, and professional.

- Have multiple trusted readers review your drafts (advisors, mentors, writing centers).

Other Written Components

- Work and Activities Section (AMCAS/AACOMAS):

- Choose your “most meaningful” experiences strategically.

- Emphasize impact, responsibilities, and reflection, not just job descriptions.

- Secondary Essays:

- Prepare common themes in advance (e.g., diversity, “Why our school?”, dealing with adversity).

- Tailor answers to each school’s mission and values.

8. Extracurricular Activities, Leadership, and Community Service

Your life outside the classroom demonstrates how you manage time, pursue your interests, and contribute to your community—key factors in Medical School admissions decisions.

Types of Valuable Extracurriculars

Community Service (especially non-clinical)

- Tutoring, mentoring, food banks, shelters, outreach to underserved communities.

- Shows compassion, altruism, and long-term commitment.

Leadership Roles

- Positions in student organizations, premed clubs, cultural groups, or sports teams.

- Demonstrates responsibility, initiative, and ability to work with others.

Teaching or Mentoring

- Peer tutoring, teaching assistant roles, youth mentorship.

- Highlights communication skills and patience—qualities essential in physicians.

Hobbies, Athletics, and the Arts

- Sports, music, writing, or creative pursuits.

- Show that you are well-rounded and able to maintain balance.

Making Extracurriculars Count

- Prioritize depth over breadth: long-term involvement in a few major activities is better than a scattered list of short-term ones.

- Seek progression of responsibility: member → officer → leader.

- Reflect on how these experiences have shaped your values and skills—and be ready to discuss them in interviews.

9. Developing Interpersonal Skills and Emotional Intelligence

Modern medicine demands more than clinical knowledge. Physicians must communicate clearly, work on teams, and respond empathetically to patients from diverse backgrounds.

Core Non-Cognitive Competencies

Medical Schools look for:

- Communication skills (verbal and written)

- Empathy and compassion

- Teamwork and collaboration

- Ethical judgment

- Resilience and adaptability

How to Build and Demonstrate These Skills

- Engage in team-based projects (research, group coursework, student organizations).

- Work in roles that require customer service or interpersonal engagement (e.g., patient-facing jobs, tutoring, resident assistant).

- Seek constructive feedback from mentors and supervisors.

- Practice active listening during clinical and volunteer interactions:

- Maintain eye contact, summarize what others say, ask clarifying questions.

- Reflect on emotionally challenging situations and how you responded.

These competencies often come through in interviews, letters of recommendation, and your descriptions of activities, so be intentional about developing them.

10. Diversity of Background, Perspectives, and Experiences

The healthcare system serves a diverse population, and Medical Schools aim to train physicians who reflect and can effectively care for that diversity.

What “Diversity” Can Mean in Medical School Admissions

Diversity is broad and may include:

- Socioeconomic background

- Race, ethnicity, culture, language

- Geographic upbringing (rural, urban, international)

- Educational path (first-generation college student, non-traditional applicant)

- Life experiences (military service, caregiving responsibilities, significant adversity)

- Unique skills or perspectives (global health exposure, advocacy work, entrepreneurship)

How to Highlight Your Unique Perspective

- Reflect on how your background has shaped your values, resilience, communication style, and interest in medicine.

- Use secondary essays and diversity prompts to:

- Describe specific experiences that changed your understanding of health or equity.

- Explain how you will contribute to your Medical School community and future patients.

- Be authentic—don’t force a narrative. Every applicant has a story worth telling, even if it doesn’t fit a traditional mold.

Putting It All Together: Strategic Application Tips for Premeds

To navigate all these prerequisites effectively, think strategically and longitudinally:

- Start planning in your first or second year of college, even if your path changes.

- Regularly meet with a premed advisor to review your course plan, Clinical Experience, and timeline.

- Track all experiences (dates, hours, supervisors, reflections) in a simple document or spreadsheet.

- Build a balanced profile that includes:

- Solid academics and MCAT Preparation

- Sustained Clinical Experience and community service

- At least some exposure to research or scholarly work

- Leadership and evidence of strong interpersonal skills

FAQs: Medical School Prerequisites and Preparation

Q1: How important is GPA compared to the MCAT for Medical School admissions?

Both are critical, but they serve slightly different purposes. GPA reflects long-term academic performance and consistency, while the MCAT is a standardized snapshot of your readiness across key content areas. A strong MCAT can sometimes help offset a slightly lower GPA (or vice versa), but significant weaknesses in either can limit your options. Aim to be competitive in both, and use trends (e.g., strong upward GPA, MCAT improvement) to your advantage.

Q2: Do all Medical Schools require the same prerequisite courses?

No. While many schools share a common core (Biology, Chemistry, Physics, English, often Biochemistry), specific requirements vary. Some schools emphasize competencies over strict course lists, while others have detailed credit and lab requirements. Always review each school’s website or official admissions guide early and confirm you will meet their standards before applying.

Q3: Is research experience necessary for Medical School applications?

Research is not strictly required at all schools, but it is highly beneficial, especially for MD programs and research-oriented institutions. It demonstrates analytical thinking, exposure to the scientific process, and comfort with evidence-based reasoning. If you are aiming for MD/PhD or academic medicine, substantial research experience is expected.

Q4: How much Clinical Experience do I need before applying?

There is no strict hour requirement, but most successful applicants have at least 100–150 hours of meaningful Clinical Experience, and many have several hundred. What matters most is that you:

- Have firsthand exposure to patient care and physician roles.

- Can clearly explain how these experiences influenced your decision to pursue medicine.

- Show consistency and commitment over time.

Q5: Can extracurricular activities and leadership roles really impact my Medical School application?

Yes. Admissions committees want to see that you are more than your grades and test scores. Sustained involvement in extracurricular activities, leadership positions, service, and hobbies:

- Demonstrates time management and resilience.

- Highlights your ability to work with others and contribute to a community.

- Provides rich experiences you can draw on in essays and interviews.

Preparing for Medical School is a multi-year, multi-dimensional process. By intentionally meeting these top prerequisites—academics, MCAT Preparation, Clinical and research experience, strong letters, compelling personal narrative, and personal growth—you set yourself up not only for a successful application but also for a fulfilling, sustainable career in medicine.