Most pre‑med advice quietly assumes you do not have a life‑or‑death situation at home. That advice does not apply to you.

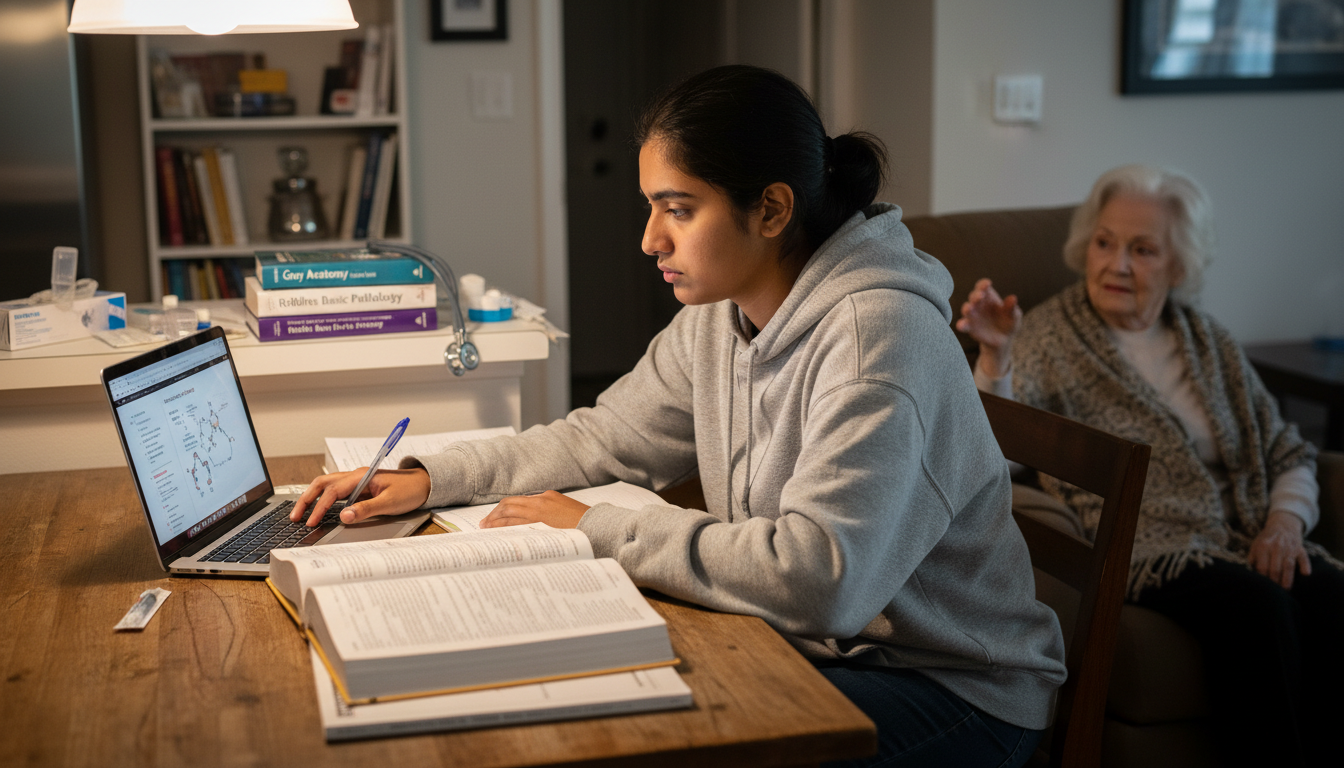

If you’re a pre‑med caring for a parent with cancer, a sibling with disabilities, or a grandparent with dementia, you’re playing this game on “expert mode” while everyone else is on “normal.” You don’t need pep talks. You need tactics that work in this reality: interrupted nights, last‑minute appointments, emotional exhaustion, and grades that cannot tank.

This is the Situation Handler approach: if this is your situation, here is exactly what to do to preserve your GPA and your sanity.

1. Step One: Decide What Actually Matters Right Now

Before schedules, before study hacks, you need a clear decision: What is the priority hierarchy for this season?

For most caregiving pre‑meds, it’s something like:

- Your own physical and mental stability (sleep, health, minimal burnout)

- Essential caregiving tasks that only you can do

- Core academic survival: GPA in key courses, prerequisites, staying enrolled

- MCAT and extras (research, volunteering, leadership) as adjustable, not fixed

Reverse that list and you will break. Not “maybe”. You will.

Build a “Non‑Negotiable / Negotiable” List

Take 15 minutes and write three columns:

Non‑Negotiable Academics

- Being full‑time vs part‑time? (depends on financial aid and visas)

- Minimum GPA you need to keep scholarships (e.g., 3.3 overall)

- Critical prerequisite courses where you must perform well (Gen Chem, Org Chem, Bio, Physics)

Negotiable Academics

- Number of courses per term

- When you take particularly hard sequences (e.g., not Org Chem + Physics + caregiving crisis in the same term)

- Timing of MCAT (you can push this back a year; med school will still be there)

Negotiable Life Stuff

- Club memberships

- Non‑clinical volunteering

- Social events every weekend

- Extra jobs that are “nice money” but not “keep the lights on”

This is your filter. When a crisis hits—ER visit, chemo reaction, behavioral crisis—you look at that list and decide what to drop without panic. GPA is preserved by planned sacrifices, not by trying to hang onto everything and losing it all.

2. Planning Your Course Load Around an Unpredictable Life

The standard pre‑med timeline assumes stability. You don’t have that. So you design around volatility.

Strategy: Schedule for Maximum Flexibility, Not Maximum Speed

Ask yourself: “If we have a major health event mid‑semester, which classes can survive it?”

Tactics:

- Limit simultaneous “killer” courses.

Don’t take:- Organic Chemistry + Physics + upper‑division Bio lab in one semester

while you’re in the middle of: - A new diagnosis

- Active chemo/immunotherapy

- Rehabilitation phase after stroke or surgery

- Organic Chemistry + Physics + upper‑division Bio lab in one semester

Instead, do:

Organic Chemistry + 2 lighter, more predictable classes (e.g., Psych, Sociology, an online humanities course)

Or Physics + 1 upper‑div Bio + 1 non‑lab class

Front‑load predictable work, back‑load flexible work.

Choose:- Asynchronous online classes when possible

- Professors known to be organized (syllabus posted early, clear calendars)

- Sections with recorded lectures

Intentionally extend your timeline.

Taking 5 years instead of 4 for undergrad is not failure. For caregiving pre‑meds, it’s often the smarter play. A 3.7 over 5 years with strong caregiving narrative is more competitive than a 3.2 in 4 years while white‑knuckling everything.

If your advisor says “Medical schools don’t like extended timelines,” translate that as: “I’m used to cookie‑cutter applicants.” Many adcoms will actually respect a thoughtful, honest reason for a longer path—especially caregiving.

Protecting Yourself With Drop and Withdrawal Tactics

You must know:

- Add/drop deadlines

- Withdrawal deadlines

- What a W means at your institution

- How many W’s start raising questions

Your rule: use a W to protect GPA when needed, but not as a habit.

Example scenario:

- Mid‑term, your mom is hospitalized for complications

- You’re failing Organic II but holding As in Psych and Spanish

- You’re past drop but before W deadline

In this situation:

- Talk to the Org II professor and your advisor right away

- If there is no realistic way to pull the grade up (you’re at 55% mid‑term), and caregiving will continue, take the W

- Protect your overall science GPA and plan to retake when life is more stable

That one W, explained by caregiving in your application, is far better than a string of C’s.

3. Studying in a House Where Interruptions Are Inevitable

You don’t get long, quiet, library days. You get 20 minutes between helping someone to the bathroom, food prep, or monitoring meds.

So we design for interruption‑resistant studying.

Use the “15‑Minute Chunk” Rule

Assume any study block can be cut short. Every chunk should be complete in itself. That means:

- Pre‑define tiny tasks:

- “Review 10 Anki cards from Biochem”

- “Write 3 bullet points summarizing today’s lecture”

- “Work through 2 practice physics problems”

- Keep a running “micro‑tasks” list in your notes app. When you get 10–20 minutes, you already know what to do.

Make Your Notes Crisis‑Proof

You might have to leave mid‑lecture or mid‑chapter. Design your material so you can drop and pick up quickly.

Concrete methods:

One‑page summaries per lecture/chapter.

Even if messy, have:- Key formulas

- Definitions

- 3–5 “if I remember nothing else, remember this” points

Use consistent highlight or margin symbols

- “★” = must know for exam

- “?” = need clarification

- “R” = review again

This way, when your next study moment is at 11:30 pm after everyone’s asleep, you’re not re‑figuring what matters. You just follow your own system.

Choose Study Modes That Match Your Reality

If you’re:

- Driving to appointments → use audio: recorded lectures, Anki audio, explanations you dictate to yourself

- Sitting in waiting rooms → use flashcards or tablet PDFs; don’t bring your whole backpack

- Doing repetitive caregiving tasks → use low‑cognitive-load review like:

- Listening to MCAT content review

- Repeating pathways or terms out loud (quietly)

(Yes, you might sound strange. It works.)

Your metric is not “perfect.” Your metric is “how much high‑yield contact time with the material can I get this week despite chaos?”

4. Talking to Professors Without Oversharing or Sounding Unreliable

Many caregiving pre‑meds stay silent because they’re afraid of sounding like they’re making excuses. That silence often costs them.

Handled well, disclosure is a tool, not a liability.

When to Say Something Early

Email your professor in week 1 if:

- You’re the primary caregiver

- Your family member’s condition is unstable

- You anticipate possible missed classes or assignments

Sample message you can adapt:

Dear Professor [Name],

My name is [Your Name], and I’m in your [Course & Section]. I wanted to share something that may impact my attendance or timing on a rare occasion this semester. I’m a primary caregiver for a close family member with a serious medical condition.

I’m fully committed to this course and will do everything I can to meet all requirements on time. Very occasionally, there may be urgent situations (hospitalizations, medical emergencies) that I can’t predict. When that happens, I’ll notify you as soon as possible and ask about how best to stay on track.

Could you please let me know your general policies on missed quizzes/exams and whether there are recommended steps I should follow if an emergency occurs?

Thank you for your understanding,

[Your Name]

[Student ID]

You’re not asking for extra credit or special breaks. You’re signaling: “I take this seriously; here is why sometimes I may not be perfect; I want to do this right.”

When a Crisis Actually Hits

As soon as reasonably possible, send a short, specific update:

Dear Professor [Name],

I wanted to let you know that I’m currently dealing with an acute medical emergency with my [relationship], for whom I’m the primary caregiver. I may need to miss [today’s class / this week’s lab / the quiz scheduled for X].

I’m still committed to keeping up with the course. Would it be possible to [make up the quiz / access lecture recordings / discuss options to stay current] once things stabilize, likely by [rough estimate]?

Thank you for your consideration,

[Your Name]

No medical details. No dramatic language. Professional, honest, brief.

Most professors will work with you if you communicate early and follow through.

5. Protecting Your GPA by Being Ruthlessly Strategic

You don’t have the luxury of “oh well, I’ll just do better next time.” You must think like someone managing a fragile vital sign.

Know Your Numbers Every Week

Once a week, sit down with:

- Current grade in each class

- Upcoming major assignments and exams

- Your realistic capacity for the week (e.g., “Dad has two oncology visits and one infusion; I’ll lose ~2 full days”)

Then:

- Assign “red / yellow / green” to classes

- Red = at risk: grade borderline, or major assessment this week

- Yellow = stable but watch

- Green = safe

You always defend your “red” classes first.

Concrete behavior:

- If Org Chem is red and Psych is green, study Org Chem first, even if Psych is more pleasant.

- If you only have 90 minutes of good brainpower today, put 60 into the hardest, most time‑sensitive class and 30 into light review.

Don’t Let Pride Kill Your GPA

Common trap: “I can handle 17 credits like everyone else.” Maybe you could in a perfect world. You don’t live there.

Serious caregiving + STEM load often means:

- 12 credits is healthy

- 14 is pushing it

- 16–18 is self‑sabotage

A 3.8 at 12 credits/semester is more attractive than a 3.1 at 18 credits with burnout. Medical schools never say, “We rejected them because they didn’t take enough credits while caring for a sick parent.”

6. Mental Health: Avoiding the Two Most Dangerous Extremes

Caregiving pre‑meds usually swing between:

- “I must be strong; I don’t need help”

- “I’m drowning; I want to quit everything”

You need a middle path.

Build a Bare‑Minimum Self‑Maintenance Plan

Not luxury. Bare minimum. Define:

Your sleep floor:

“I do not go below X hours of sleep for more than 2 nights in a row unless it’s a true emergency.”

For many people, X should be 6. You decide your number, but make one.One daily mental release valve (~10–20 minutes):

- Walk around the block with headphones

- Quick journaling brain dump

- Short workout or stretching

- Sitting in the car alone after an appointment, doing nothing

This is not optional “self‑care.” It’s maintenance so you do not snap on your loved one, your professor, or yourself.

Use Campus or Community Resources Without Guilt

If your school has:

- Counseling services

- Disability/Accessibility office

- Student support/case management

- Emergency funds or food pantry

You qualify more than most.

You can request:

- Flexible attendance policies

- Priority in scheduling classes around your caregiving hours

- Quiet test environments if your home is chaotic

- Extensions under documented extenuating circumstances

None of this will show up on your transcript as “weakness.” It will show up indirectly as “this student held it together.”

7. Turning Caregiving into a Strength in Your Future Application

You’re not doing this for the narrative. But you will eventually need to explain your path.

Handled correctly, caregiving can:

- Explain lighter course loads or a fifth year

- Contextualize a few W’s or a bad semester

- Demonstrate resilience, empathy, systems‑level understanding of healthcare

What to Track Now for Later

You don’t have to journal every day. Just keep a simple running log (could be Notes app or Google Doc) with:

- Dates of major events (hospitalizations, new diagnoses, surgeries)

- Rough number of hours/week you spend caregiving (transportation, medication management, ADLs—activities of daily living)

- The kinds of tasks you actually do:

- Medication organization and administration

- Communicating with healthcare teams

- Translating information between providers and family

- Assisting with feeding, mobility, hygiene

- Managing insurance, appointments, paperwork

Why this matters:

When you write your personal statement or secondaries, you can be specific instead of vague. Specific builds credibility. Vague sounds like an excuse.

Example later explanation in an application:

During my sophomore and junior years, I served as the primary caregiver for my grandmother after she developed advanced heart failure and later dementia. I coordinated her medications, communicated with her cardiology team, and assisted with daily activities, often spending 25–30 hours per week on her care.

This responsibility required me to extend my graduation timeline and at times reduce my course load, but it also gave me a close, sustained view of chronic disease management and the gaps families face in navigating healthcare.

That’s a story most admissions committees take seriously.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Should I take a leave of absence from school while caregiving is intense?

Possibly. Consider a leave if:

- You’re the only available caregiver, and the situation is truly 24/7

- Your grades are already crashing (multiple C’s/D’s) despite genuine effort

- You feel physically or mentally unsafe continuing as you are

Talk to:

- Academic advising

- Financial aid (to understand loan/aid implications)

- A trusted clinician (for your own health)

A documented leave with a clean break and later strong performance is better than three consecutive semesters of poor grades.

2. Will medical schools hold a lighter course load against me because of caregiving?

In most cases, no—if:

- Your GPA is strong in the courses you do take

- You clearly explain the caregiving context in your application

- You eventually show that you can handle rigorous science coursework when life stabilizes

What worries committees more is poor performance in key prerequisites, not that you took 12 credits instead of 18 during a crisis year. They read your file in context when you give them that context.

3. How do I handle the MCAT timeline as a caregiver?

Treat the MCAT as:

- A long‑range project, not a cram event

- Something to take when you’ve had at least a few relatively stable months to prep

Strategies:

- Plan a 9–12 month low‑intensity study schedule instead of 3–4 brutal months

- Use question banks and spaced repetition that fit into small time blocks

- Be prepared to push your test date once if there’s a major health event

Do not take the MCAT “just to see how I do” when your life is on fire. A weak score still follows you.

4. Should I talk about my caregiving role in my personal statement or secondaries?

Yes, if:

- Caregiving has significantly shaped your path, timeline, or motivation for medicine

- You can describe it with specificity and reflection, not self‑pity

You might:

- Use caregiving as your central narrative in the personal statement, or

- Address it in “challenge,” “diversity,” or “impact of COVID/family responsibilities” secondary prompts

Avoid framing it as “the reason I couldn’t do X.” Instead, frame it as “the experience that taught me Y and required me to make Z decisions.”

5. How do I deal with guilt—feeling like I’m failing both as a caregiver and as a student?

This guilt is common and corrosive. Practical steps:

- Define realistic expectations: What would “doing my best in this season” actually look like in measurable terms? (e.g., 12 credits, B+ or better, 6 hours sleep)

- Talk to at least one neutral professional (counselor, therapist, mentoring dean) about this specific guilt; they can help you adjust expectations

- Remind yourself: Medical schools admit humans with complex lives. They are not looking for people who have never had to choose between two important goods. They are evaluating how you made those choices and what you learned.

You are not failing if you cannot be a full‑time nurse, full‑time student, and full‑time robot. You are navigating impossible trade‑offs as thoughtfully as you can.

Key Takeaways

- You must design your schedule, study habits, and communication around volatility, not perfection.

- Protect your GPA through early communication, strategic course loads, and using withdrawals or extended timelines when needed.

- Caregiving, handled with honesty and specificity, can become one of the most credible strengths in your eventual medical school application—not a hidden shame.