Residency is often described as a marathon run at sprint pace. It’s the bridge between medical school and independent practice, a time when physicians in training shoulder real responsibility for patient care while still learning the craft. At the center of this experience lies one of the most debated issues in modern medical training: residency work volumes and work hours.

Understanding how much residents actually work, how those hours affect physician well-being and patient care, and what can be done to create healthier training environments is essential for anyone considering or currently in residency. This guide takes a deeper, more practical look at residency work hours, beyond the policy language, and into the lived reality.

Understanding Residency Work Volumes and Why They Matter

Residency work volume refers not just to the number of hours you’re in the hospital, but also to the intensity and complexity of the work you do during those hours. Two residents may both work 70 hours a week, yet have dramatically different experiences depending on:

- Patient volume and acuity

- Documentation and administrative burden

- Availability of ancillary staff

- Specialty-specific demands

- Call schedules and night float systems

For residency applicants and current trainees, understanding work volume is crucial for several reasons:

- It shapes your daily life and mental health

- It affects your learning and clinical development

- It influences your sense of professional identity and satisfaction

- It plays a role in career choices and long-term retention in specialties

Residency is designed to be challenging. The goal is to expose you to enough clinical volume and complexity that you graduate competent, confident, and ready for independent practice. The question is where to draw the line between “rigorous training” and “unsafe overwork” that fuels burnout and compromises care.

Historical Context: From 100-Hour Weeks to Duty Hour Reform

For much of the 20th century, residency hours were extreme. It was not uncommon for residents—especially in surgical and internal medicine programs—to work 100–120 hours per week, sometimes going 36 hours or more without sleep. The underlying assumptions were:

- Medicine must be learned by immersion

- Continuity of care is paramount

- Endurance is a marker of dedication and toughness

This model began to face serious scrutiny as research emerged connecting sleep deprivation to cognitive impairment, increased medical errors, motor vehicle accidents, and long-term mental health issues. High-profile patient safety incidents, such as the Libby Zion case in the 1980s, galvanized public and regulatory attention.

In response, regulatory bodies, including the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), implemented formal duty hour standards in 2003, later revised in 2011 and updated again in subsequent years. These reforms marked a major cultural shift: resident well-being and patient safety became explicit priorities, not just assumed byproducts of training.

ACGME Duty Hour Regulations: What the Rules Actually Say

To understand residency work volumes, it’s important to know the current ACGME duty hour framework. Specific details can vary slightly by specialty and year, but core principles are consistent.

Key ACGME Duty Hour Standards

Maximum Weekly Hours

- Residents must not work more than 80 hours per week, averaged over a four-week period, including all in-house call and moonlighting.

In-House Call and Daily Limits

- Maximum of 24 hours of continuous scheduled clinical duties.

- Up to 4 additional hours allowed for transitions of care, education, and documentation, but no new patient admissions during that period.

Time Off Between Shifts

- A minimum of 8 hours off between scheduled duty periods;

- 10 hours off is preferred and often required after extended shifts.

- After 24+ hours of in-house call, residents should have at least 14 hours off, depending on specialty rules.

Days Off

- At least one day free of clinical and educational duties every week, averaged over four weeks (i.e., four days off in a typical four-week block).

Night Float and In-House Night Call

- Programs must ensure that night shifts are structured to prevent cumulative fatigue and to maintain opportunities for education and supervision.

These regulations are designed to create guardrails—but they do not define the entire experience. Within the 80-hour framework, your daily schedule, call structure, and workload intensity can look very different across specialties and institutions.

Variation by Specialty and Training Environment

Even with the same numeric limits, work volume feels different depending on where and what you’re training in:

- High-acuity inpatient specialties (e.g., Internal Medicine, General Surgery, Emergency Medicine, OB/GYN, ICU fellowships) often have intense, unpredictable workloads with frequent nights and weekends.

- Procedure-heavy fields (e.g., Surgery, Orthopedics, Neurosurgery) may pack long operative days with limited downtime.

- More outpatient-focused specialties (e.g., Family Medicine, Psychiatry, Dermatology) may have more structured schedules, though inpatient months and call can still be taxing.

- Large academic centers may leverage fellows, advanced practice providers (APPs), and ancillary staff, reducing some burden. Conversely, they may have higher patient volumes and complexity.

- Smaller community programs may offer closer attending supervision and sometimes lighter call—but may also rely heavily on residents for coverage.

For applicants, this means simply asking “Do you follow ACGME duty hours?” is not enough. You need to understand how those hours feel in real life.

The Reality Behind the Numbers: What Residents Actually Experience

Even with ACGME regulations in place, resident experiences vary widely. Many programs work hard to comply and prioritize well-being. Others struggle due to systemic pressures.

When Policy Meets Practice: Why Hours Can Creep Up

Several recurring themes explain why some residents feel they routinely exceed 70–80 hours or feel overburdened even within the technical limits:

1. Patient Care Demands and Staffing Gaps

Residents are often the backbone of inpatient care. When:

- Patient censuses surge

- Hospitalist or attending coverage is stretched

- There are not enough APPs or ancillary staff

residents may feel pressure to stay late to complete notes, update families, or follow up labs and consults. While attending physicians usually want residents to go home, the reality of unfinished work—and residents’ sense of responsibility to patients—can lead to frequent “staying an extra hour or two,” night after night.

2. Documentation and Administrative Burden

Electronic health records, prior authorizations, discharge summaries, and endless checklists add hours of “invisible work.” Even when clinical tasks are done, charting lingers.

Many residents describe “pajama time”—working on notes from home, which may not always be captured as duty hours, despite technically counting toward work volume.

3. Cultural Norms and Hidden Expectations

Some programs have made genuine cultural shifts, openly encouraging residents to go home when their shift ends and reinforcing duty hour compliance. Others still implicitly value:

- “Face time” as a sign of dedication

- Staying late with the team to show commitment

- Taking extra work without complaint

This culture can quietly pressure residents into extending their workdays, under-reporting hours, or normalizing chronic fatigue.

4. Educational and Research Expectations

Residency is not just service—it’s also education. Conferences, simulations, morbidity and mortality (M&M) rounds, and didactics are critical for learning but often stack onto already busy clinical days.

Add research requirements, QI projects, or leadership roles (chief resident, committee memberships), and you may effectively add several hours per week on top of clinical duties.

5. Differences Across Rotations and PGY Levels

Work volumes can fluctuate dramatically:

- Intern year (PGY-1): Often the most physically demanding, with heavy floor work, cross-cover, and night float.

- Senior years: Less scut work but more responsibility—leading complex codes, family meetings, and supervising interns can add emotional load even if raw hours decrease.

- ICU, ED, and surgical months: Typically front-loaded with high acuity and long shifts.

- Electives or ambulatory blocks: May offer comparatively lighter schedules and recovery time—if protected appropriately.

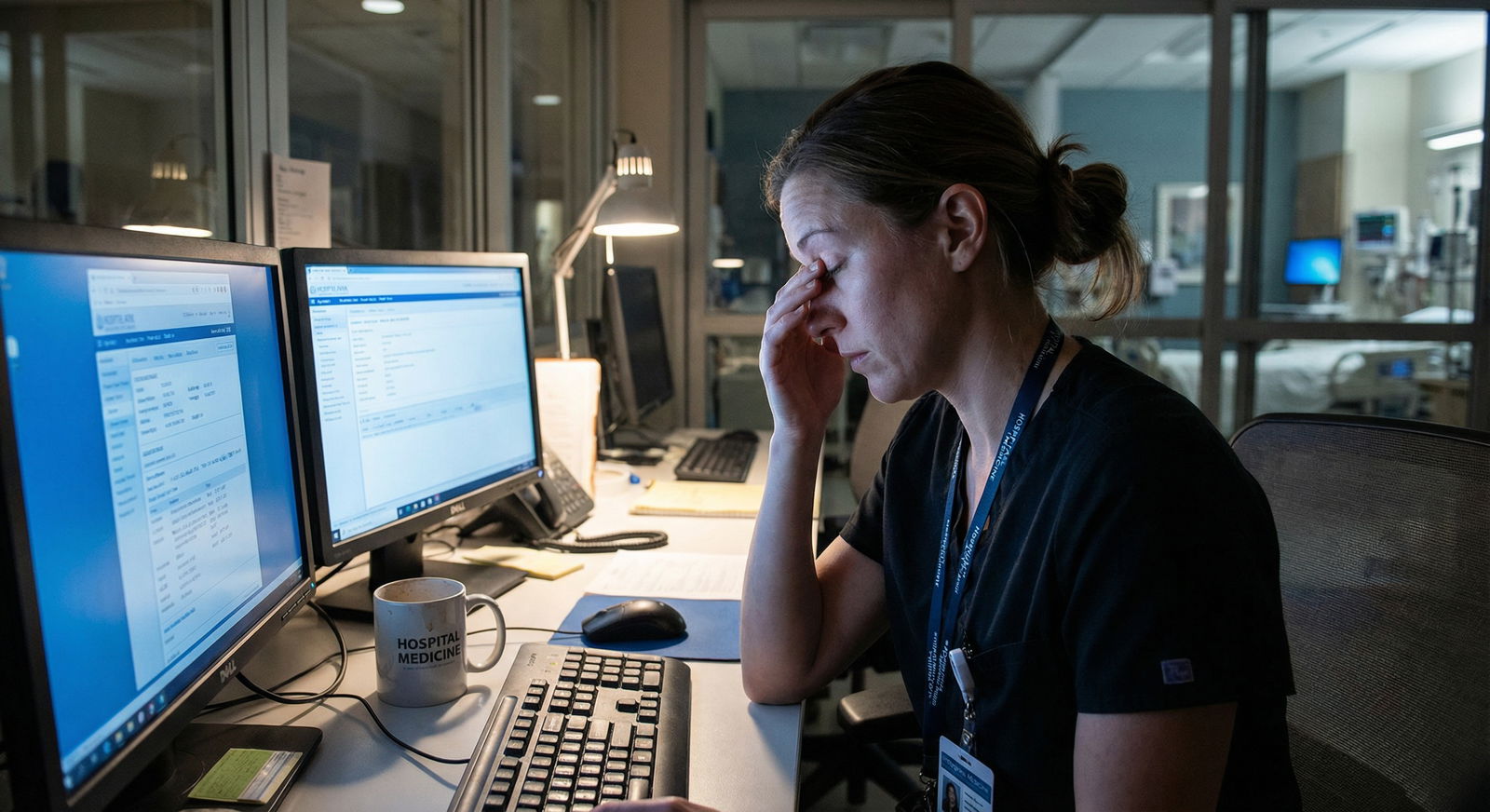

The Impact of High Work Volumes on Resident and Physician Well-Being

Residency is intense by design, but excessive or poorly structured work hours have tangible effects on both residents and patients.

1. Burnout, Moral Injury, and Emotional Exhaustion

Burnout among residents is consistently reported at high rates, often 40–70% depending on specialty and setting. Classic signs include:

- Emotional exhaustion and feeling “used up”

- Depersonalization—cynical or detached attitudes toward patients

- Reduced sense of personal accomplishment

In addition, many trainees experience moral injury, the distress that arises when systemic constraints prevent them from delivering the level of care they know is right—such as discharging patients too early or rushing through visits due to volume.

High work volume is not the only driver of burnout, but it amplifies:

- Emotional load from difficult cases

- Sleep deprivation and cognitive fatigue

- Isolation from support systems outside medicine

2. Cognitive Performance and Patient Safety

Sleep deprivation and prolonged wakefulness have well-documented effects similar to alcohol impairment. Research has linked excessive resident hours and overnight call to:

- Slower reaction times and impaired judgment

- Higher rates of diagnostic and medication errors

- Increased needle-stick injuries and motor vehicle crashes post-call

For residents, this creates a painful paradox: the very intensity meant to build competence can, when excessive, undermine performance and threaten patient safety.

3. Mental Health: Anxiety, Depression, and Suicidality

Multiple studies have documented elevated rates of:

- Depression and depressive symptoms

- Anxiety disorders

- Suicidal ideation and, tragically, completed suicide among physicians in training

Contributing factors include long work hours, lack of sleep, emotional trauma from clinical events, stigma around help-seeking, and limited time to access care. Many residents do not feel safe disclosing mental health struggles, fearing professional repercussions.

4. Work-Life Integration and Relationships

Extended and irregular work hours strain personal relationships and life outside medicine:

- Difficulty maintaining partnerships and friendships

- Missed family events, holidays, and milestones

- Disrupted exercise, nutrition, and hobbies

Over time, this can foster resentment, isolation, and feeling that life is being “on hold” during training. These experiences often shape long-term career decisions, including specialty choice and whether to remain in clinical practice.

Addressing Residency Work Volume Challenges: What Can Be Done

Improving residency work hours and volumes requires action at multiple levels: individual, program, institutional, and regulatory. While residents cannot change everything, there are meaningful levers for change.

1. Strengthening Policy, Oversight, and Resident Advocacy

Know Your Rights and the Rules

Residents should be familiar with:

- ACGME duty hour standards

- Program-specific policies (e.g., moonlighting rules, call caps)

- Processes for reporting violations (anonymously if needed)

Understanding the rules gives you a foundation for constructive advocacy.

Engage in Program and Institutional Governance

Practical ways to influence change:

- Serve on residency program committees or GMEC (Graduate Medical Education Committee)

- Participate in ACGME surveys thoughtfully and honestly

- Provide concrete feedback during program evaluations and retreats

Residents often have more influence than they realize when they speak collectively and offer specific, data-driven suggestions.

2. Shifting Culture: From Endurance to Sustainable Excellence

Cultural change is slow but possible. Programs can promote healthier norms by:

- Explicitly stating that well-being and safety are core values, not afterthoughts

- Modeling appropriate behavior—attendings leaving on time, taking PTO, seeking help when needed

- Normalizing conversations about burnout, therapy, and mental health support

- Celebrating clinical excellence without glorifying overwork (“I stayed 36 hours and…”)

Residents can contribute by supporting colleagues who need time off, avoiding “badge of honor” narratives around extreme hours, and checking on each other after difficult rotations or events.

3. Improving Staffing, Workflow, and Support Systems

Concrete structural changes can significantly reduce unnecessary workload:

- Utilizing APPs and ancillary staff for routine tasks (medication reconciliation, discharges, certain consults)

- Streamlining documentation with templates, dictation tools, and smart phrases

- Improving discharge planning and case management to prevent last-minute crises

- Re-designing handoffs to be more efficient and safer, reducing duplication of work

Residents can help identify bottlenecks and low-yield tasks that add hours without adding educational value, then propose alternatives.

4. Building Feedback Loops and Data-Driven Improvement

Programs that take duty hours seriously tend to:

- Track work hours transparently and review them regularly

- Use anonymous surveys and town halls to gather resident input

- Perform “workload audits” on high-intensity rotations

- Adjust schedules, caps, and staffing in response to data

Residents can contribute by accurately logging hours, even when it feels uncomfortable. Under-reporting hours may feel like “helping the program,” but it hides problems that need to be addressed.

Practical Strategies for Residents to Cope with High Work Volumes

While systemic reform is essential, residents also need realistic strategies for surviving—and ideally growing—within the current system.

Time Management and Efficiency on the Wards

- Standardize your workflow: Develop checklists for prerounds, notes, and discharges. Consistency saves cognitive effort.

- Prioritize ruthlessly: Focus on tasks that impact patient safety first (vitals, critical labs, acute changes), then documentation and “nice-to-haves.”

- Maximize team-based care: Delegate appropriately to medical students, nurses, and ancillary staff; clarify roles during morning huddles.

- Batch tasks: Group pages, orders, and chart reviews when possible to minimize task-switching.

Protecting Sleep and Recovery

- Use sleep hygiene strategies on nights off: dark room, consistent routine, limit screens before bed.

- On night float or call months, protect post-call time aggressively; avoid “just a few more notes” eating into recovery.

- Nap strategically when possible during overnight shifts (with attending/team permission and safe coverage).

Safeguarding Mental Health and Relationships

- Identify at least one trusted colleague or mentor you can be honest with about struggles.

- Use available resources: employee assistance programs, resident wellness centers, therapy benefits.

- Schedule intentional connection with family/friends on lighter days—even short check-ins can help combat isolation.

- Set boundaries where possible around days off and vacations; treat them as non-negotiable recovery periods.

Planning for the Long Game

- Remember that residency is time-limited; identify the rotations and years likely to be most intense and plan accordingly (housing, partner expectations, childcare if applicable).

- Reflect periodically on your values and long-term goals: What kind of physician do you want to be? What practice environment will support your well-being after training?

- Use your residency experience to inform—not silence—your preferences about future work hours, call schedules, and practice settings.

The Road Ahead: Rethinking Residency Work Hours and Training Models

The truth about residency work volumes is nuanced. Some key realities coexist:

- Rigorous, high-volume clinical exposure is essential for developing competent, independent physicians.

- Excessive, poorly structured hours harm residents and patients and drive physician burnout and attrition.

- Duty hour regulations have improved conditions compared to 20–30 years ago, but implementation and culture remain uneven.

- Meaningful solutions require both systemic reform and individual coping strategies, along with ongoing research and innovation in medical education.

As discussions about physician well-being and burnout continue to gain prominence, residency work hours will remain central to the conversation. Future directions may include:

- More competency-based training rather than time-based models

- Greater use of simulation to supplement clinical exposure

- Team-based care models that distribute workload more sustainably

- Enhanced support for mental health and well-being embedded into training

For current and future residents, the challenge is to engage with these issues thoughtfully—to advocate for healthier systems while also developing the skills and resilience needed to practice medicine sustainably.

FAQs: Residency Work Hours, Burnout, and Physician Well-Being

1. How strictly are ACGME residency work hour rules enforced, and what happens if they’re violated?

ACGME duty hour rules are taken seriously, especially during accreditation reviews. Programs must track resident hours and report compliance. If violations are frequent or systemic, the ACGME can issue citations, require corrective action plans, or, in severe cases, place programs on probation. Residents can report concerns internally to program leadership or anonymously through ACGME surveys and institutional channels. Accurate reporting is essential—under-reporting hours hides problems that need attention.

2. Are certain specialties consistently more demanding in terms of work hours and volume?

Yes. While experiences vary by institution, certain specialties are typically more time- and intensity-demanding:

- Generally higher: General Surgery, Neurosurgery, Orthopedics, OB/GYN, Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine, some subspecialty fellowships (e.g., critical care).

- Generally more structured or outpatient-focused (though still demanding): Family Medicine, Pediatrics (varies), Psychiatry, Dermatology, Pathology, Radiology.

Remember that within each specialty, individual programs can range from relatively balanced to very intense, so program culture and structure are just as important as the specialty label.

3. What are early warning signs of burnout or declining well-being during residency?

Common early signs include:

- Chronic exhaustion despite sleep opportunities

- Increasing cynicism or detachment from patients and colleagues

- Declining empathy or feeling “numb” to patient suffering

- Difficulty concentrating, forgetfulness, or more frequent mistakes

- Loss of interest in activities you previously enjoyed

- Irritability, anger, or emotional volatility

Recognizing these signs early and reaching out—for peer support, mentorship, or professional help—can prevent progression to more severe burnout or depression.

4. What concrete steps can residents take if they feel their program is ignoring duty hour rules or well-being concerns?

Options include:

- Documenting patterns: keep a private record of hours and specific incidents.

- Speaking with chief residents or trusted faculty mentors for advice.

- Bringing concerns to your program director or GME office with specific examples and proposed solutions.

- Using anonymous reporting channels if available, including ACGME surveys.

If internal efforts fail and patient or resident safety is at risk, residents may consider contacting the ACGME directly. Involving peers and presenting concerns as a group often carries more weight and protects individuals from feeling isolated.

5. How can residency applicants realistically assess work hours and culture during interviews?

Beyond asking, “Do you follow ACGME rules?” consider:

- Asking residents, “What does a typical day look like on your busiest rotation?”

- Asking about average weekly hours on inpatient vs. outpatient rotations.

- Inquiring about “pajama time” and how often residents chart from home.

- Noticing whether residents seem exhausted, guarded, or fairly open and supported.

- Asking, “Can you give an example of a change the program made in response to resident feedback?”

Programs that are transparent, data-driven, and willing to discuss both strengths and challenges are more likely to prioritize resident well-being in practice, not just in marketing materials.

By understanding residency work volumes through both policy and lived experience, future and current trainees can make more informed choices, advocate more effectively, and help shape a training environment that produces excellent physicians without sacrificing their health and humanity.