Introduction: Why Residency Work Hours Matter More Than Ever

Residency training is the bridge between medical school and independent practice—a period defined by intense clinical exposure, rapid learning, and profound responsibility. It is also a time when many physicians experience the longest and most demanding work hours of their careers.

The structure of residency work hours directly affects:

- Resident well-being and mental health

- The quality and safety of patient care

- The culture and sustainability of the medical workforce

- Long-term career satisfaction and risk of burnout

The central question—Are current residency work hours sustainable?—is no longer only about whether residents can “tough it out.” It is now deeply tied to evidence on sleep deprivation, medical errors, professional development, and the future of medical education.

This article examines the history of residency work hours, current regulations, real-world resident experience, and the arguments on both sides of the debate. It then explores emerging reforms and practical strategies that residency applicants and current trainees can use to navigate work hours more safely and sustainably.

From 120-Hour Weeks to Duty-Hour Reform: How We Got Here

Understanding today’s debate about Residency Training work hours requires a look back at how the system evolved.

The Traditional Model: Endless Hours, Limited Protections

For most of the 20th century, residency training was built on an apprenticeship model:

- Residents routinely worked 100–120+ hours per week

- 36-hour in-house calls were common, often with minimal supervision

- There were no formal national limits on Work Hours or mandatory rest periods

This culture was justified by several beliefs:

- Medicine requires total immersion

- Fatigue “toughens” trainees and builds resilience

- Continuity of care is more important than sleep

- Long hours equal commitment and professionalism

However, mounting evidence and several high-profile cases challenged these assumptions. One landmark event was the Libby Zion case in the 1980s, which brought national attention to resident fatigue, supervision, and Patient Safety in teaching hospitals. This case helped catalyze reforms in New York State and influenced national conversations about duty hours.

ACGME Duty-Hour Reform: The 2003 Turning Point

In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented national duty-hour standards across all accredited residency programs. Major elements included:

- 80-hour work-week limit, averaged over 4 weeks

- Maximum 24 consecutive hours of in-house clinical duties, with up to 4 additional hours for transitions of care and educational activities

- 1 day off in 7, averaged over 4 weeks

- In-house call no more frequently than every 3rd night

- Required supervision structures and fatigue mitigation strategies

These rules were intended to address fatigue-related errors, improve resident wellness, and standardize training environments.

Subsequent Adjustments and Ongoing Controversy

In 2011, stricter limits were introduced for first-year residents (interns), capping continuous duty at 16 hours. However, based on mixed evidence and strong feedback from programs and residents, the ACGME later revised these rules in 2017:

- Interns could again work up to 24 hours of continuous clinical work, with 4 additional hours for care transitions

- Emphasis shifted from rigid shift limits toward flexible scheduling, education about fatigue, and program-level monitoring of resident outcomes

Today, while the 80-hour limit remains, the debate has shifted from “Should we limit hours?” to “What is the right balance between education, safety, and well-being—and how do we achieve it in practice?”

The Current Landscape: Regulations vs. Reality in Residency Training

What the ACGME Duty-Hour Standards Actually Require

Across most specialties, the ACGME duty-hour rules specify:

- 80 hours per week maximum, averaged over four weeks

- Minimum 1 day in 7 free from clinical responsibilities, averaged over four weeks

- Maximum 24 hours of in-house clinical duty, with up to 4 additional hours for documentation and handing off patients

- Adequate rest between shifts, often interpreted as ~10 hours off after in-house call

- In-house call typically no more than every third night, when averaged

Programs must also:

- Track duty hours and investigate violations

- Educate residents and faculty on fatigue risks

- Ensure appropriate supervision at all levels of training

On paper, the system is designed to limit the most extreme schedules of the past while preserving sufficient clinical exposure.

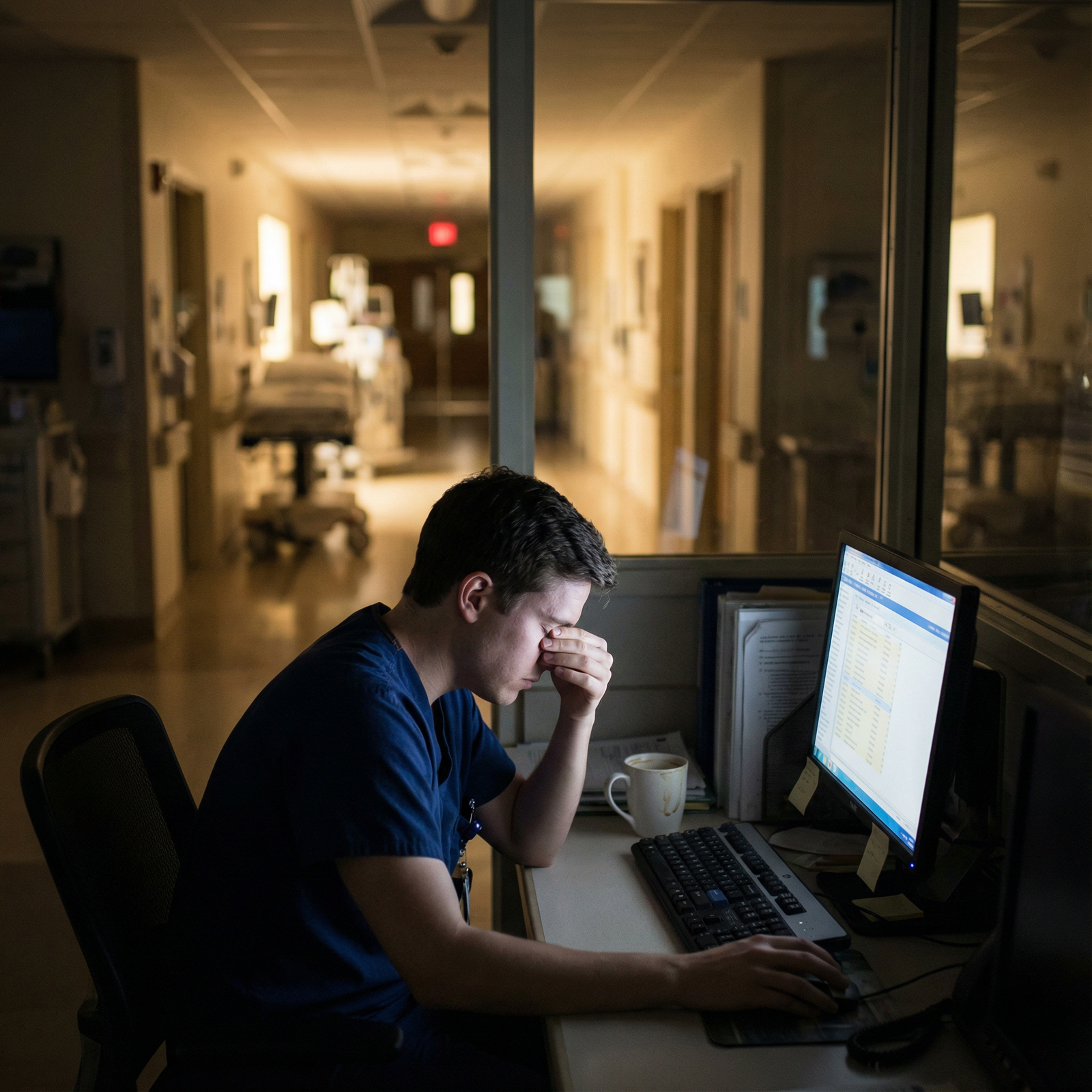

How Duty Hours Feel on the Ground: The Resident Experience

Despite formal limits, the lived experience of residents often feels very different. Many trainees report that:

- 80 hours feels near constant in high-intensity specialties (e.g., surgery, critical care, OB/GYN)

- “Non-clinical” tasks—documentation, orders, EMR inbox, calls—extend hours beyond scheduled shifts

- Pressure to “stay until the work is done” can override theoretical end times

- Underreporting duty hours sometimes occurs due to fear of penalizing the program or being perceived as weak

The impact on residents is multifaceted:

Burnout and Emotional Exhaustion

Burnout among residents remains high, often with reported rates of 40–60% depending on specialty and training year. Contributing factors include:

- Chronic sleep deprivation

- High workload and time pressure

- Emotional burden of caring for critically ill or dying patients

- Limited perceived autonomy and control over schedule

- Documentation and administrative burdens

Burnout is not just about feeling tired; it affects empathy, clinical judgment, and long-term career satisfaction.

Mental Health and Suicidality

Multiple studies have found that residents experience:

- Higher rates of depression and depressive symptoms than the general population

- Increased risk of anxiety disorders and substance misuse

- Elevated risk of suicidal ideation, particularly during early training years

Stigma, fear of career impact, and time constraints can prevent residents from seeking help, even when resources are available.

Patient Safety Concerns

Fatigue has well-documented effects on cognitive performance, similar in magnitude to being legally intoxicated. In the residency context, this may lead to:

- More frequent medication errors

- Missed or delayed diagnoses

- Poor communication during handoffs

- Reduced ability to recognize subtle clinical deterioration

While research findings are mixed—some studies show improved Patient Safety with shorter shifts, others do not—the concern about fatigue-related errors remains a core part of the work-hour debate.

Are Current Residency Work Hours Sustainable?

The question of sustainability has at least three dimensions: educational quality, resident well-being, and Patient Safety. Stakeholders disagree on how well the current system balances these.

Supporters of the Current Model: Why Long Hours Might Be Necessary

Advocates for maintaining current work-hour limits (and sometimes even for adding flexibility beyond them) emphasize the educational and professional benefits of intense exposure.

1. Clinical Volume and Procedural Competence

Becoming a competent physician requires:

- Repeated exposure to common conditions

- Direct management of serious and uncommon presentations

- Sufficient procedural volume in procedure-heavy fields

Supporters argue that:

- Shorter work weeks may reduce opportunities to see the “natural history” of disease

- Surgical trainees, for example, need high case volumes to meet competency thresholds

- Spending more time in the hospital can compress the learning curve and deepen pattern recognition

2. Continuity of Care and Ownership

Longer shifts and extended time on service allow residents to:

- Admit, diagnose, treat, and follow a patient over several critical days

- See how early decisions impact later outcomes

- Develop a sense of ownership and responsibility for patient care

Some worry that overly fragmented schedules—with frequent handoffs and strict shift limits—may undermine the development of professional identity and continuity of care.

3. Preparing for Real-World Practice

In many settings—especially in community hospitals, rural areas, or under-resourced systems—attendings still work demanding hours. Proponents of current work hours argue:

- Residency should realistically prepare trainees for the pressures of practice

- Learning to manage fatigue and maintain performance under stress is a crucial skill

- Shielding residents too much from long hours may create a mismatch between training and real-world expectations

From this perspective, the current system is demanding but ultimately necessary to produce confident, capable physicians.

Critics of the Current Model: Why the System May Not Be Sustainable

On the other side, critics contend that current duty hours remain too long, too rigid, and insufficiently humane—and that this has serious consequences.

1. Chronic Sleep Deprivation and Health Risks

Sustained 70–80-hour weeks with frequent nights and call shifts contribute to:

- Chronic sleep loss and circadian disruption

- Increased risk of cardiovascular disease, metabolic abnormalities, and impaired immune function

- Higher rates of motor vehicle accidents after overnight or extended shifts

From a public health standpoint, building a system that relies on chronically sleep-deprived physicians is inherently unsustainable.

2. Burnout, Attrition, and Long-Term Workforce Impact

High burnout and poor wellness during training are linked to:

- Increased risk of early career change or leaving clinical practice

- Decreased likelihood of practicing in high-need or underserved areas

- Lower academic productivity and engagement in teaching or research

For a healthcare system already facing workforce shortages in multiple specialties, a training model that burns out physicians early may not be viable.

3. Questionable Impact on Education Quality

Critics challenge the assumption that more hours always equal better training:

- Fatigued residents may learn less efficiently and retain less information

- Time spent on low-yield tasks (e.g., duplicative documentation) may not add meaningful educational value

- Intentional, supervised learning in more focused blocks might produce better outcomes than sheer volume

The key question is not just “How many hours?” but “How are those hours used?”

4. Evolving Expectations and Generational Shifts

Today’s trainees increasingly value:

- Work-life integration

- Mental health and psychological safety

- Flexible career paths and varied practice settings

A system designed around 20th-century assumptions about total sacrifice may not align with the values of 21st-century physicians, threatening recruitment and retention in demanding specialties.

Rethinking the Future: Paths Toward More Sustainable Residency Work Hours

The conversation is shifting from simple hour-counting to designing a more humane, evidence-informed training environment. Several strategies and reforms are emerging.

Structural and Scheduling Reforms

1. Smarter Shift Design

Instead of uniformly long shifts:

- Use shorter night shifts (e.g., 12–16 hours) where feasible

- Rotate nights in more predictable blocks to reduce circadian disruption

- Avoid “quick turnarounds” (e.g., late call followed by an early morning clinic)

Programs can experiment with:

- Night-float systems that concentrate overnight coverage in dedicated teams

- Caps on admissions per shift to limit intensity, not just duration

- Protected “golden weekends” or scheduled wellness days to allow recovery

2. Task Redistribution and Team-Based Care

Not all tasks require a physician:

- Shift certain administrative duties to scribes, care coordinators, or other team members

- Use advanced practice providers (NPs, PAs) to share service workload

- Leverage multidisciplinary teams so residents can focus more on higher-order decision-making and learning

This reduces the time residents spend on low-yield tasks and preserves energy for critical thinking, teaching, and reflection.

Cultural and Educational Shifts

3. Normalizing Help-Seeking and Saying “I’m Tired”

A sustainable system requires a culture change:

- Faculty and senior residents modeling the behavior of taking breaks, handing off safely, and acknowledging limits

- Explicitly teaching and valuing fatigue management, self-monitoring, and peer support

- De-stigmatizing the use of counseling, mental health resources, and wellness services

Programs can integrate:

- Regular check-ins with program leadership or mentors

- Anonymous reporting mechanisms for unsafe workloads

- Wellness curricula that address stress management, boundary-setting, and resilience (beyond superficial wellness talks)

4. Competency-Based, Not Time-Based, Training

Moving toward competency-based medical education (CBME) could:

- Focus more on demonstrated skills and outcomes rather than hours logged

- Allow some residents to graduate earlier if they reach required competencies

- Encourage targeted, high-yield learning rather than simply extending time on service

While full CBME implementation is complex, incremental moves in this direction can help shift the focus from endurance to mastery.

Technology, Innovation, and Patient Safety

5. Leveraging Technology to Reduce Burden

Thoughtfully implemented technology can support both wellness and Patient Safety:

- Decision support tools for drug dosing, interactions, and guideline-based care

- AI-assisted documentation to streamline notes and reduce charting time

- Telehealth options for certain follow-up visits, reducing in-person workload

- Better EMR design with fewer clicks and more intuitive interfaces

The goal is not to replace clinical reasoning, but to free residents from low-value tasks and help focus their cognitive energy where it matters most.

6. Data-Driven Pilot Programs

Several studies and pilot projects have compared:

- Standard duty-hour models vs. more flexible, longer-shift models

- Traditional call vs. night float

- Different scheduling patterns across specialties

Programs can:

- Participate in or initiate pilot duty-hour structures, with robust evaluation of outcomes

- Track not only duty hours but also wellness measures, error rates, exam performance, and patient outcomes

- Involve residents actively in designing and refining schedules

Residents applying to programs can ask about such pilots and how the program responds to data and feedback.

Practical Advice for Current and Future Residents

Even as the system evolves, there are concrete steps you can take to protect your well-being and support Patient Safety during residency.

For Medical Students and Applicants

When evaluating programs, ask:

- How often do residents approach the 80-hour limit, realistically?

- How are schedules structured—night float, traditional call, shift work?

- How does the program monitor and respond to burnout and wellness concerns?

- Are there protected didactics that are reliably honored?

- What is the culture around reporting duty-hour violations?

Speak with current residents off the record if possible. Their insights are often the most accurate reflection of day-to-day life.

For Current Residents

- Set micro-boundaries: Small practices—like taking a 5-minute break to eat or hydrate—are not luxuries; they are safety interventions.

- Use your team: Delegate appropriately, involve nurses and other professionals, and communicate early when you’re overwhelmed.

- Practice efficient workflows: Templates, checklists, and batching tasks (e.g., calling all consults at once) can reclaim crucial time.

- Monitor your limits: If you are too fatigued to be safe, speak up. Use formal channels if necessary. Patient Safety is a shared responsibility.

- Engage with leadership: Participate in residency councils or wellness committees. Residents are often the best source of creative, realistic scheduling solutions.

FAQ: Residency Work Hours, Burnout, and Patient Safety

1. What are the current ACGME regulations on residency work hours?

The ACGME generally limits residents to:

- A maximum of 80 hours per week, averaged over 4 weeks

- No more than 24 consecutive hours of in-house clinical duties, with an additional 4 hours allowed for care transitions and education

- At least 1 day in 7 free of clinical duties, averaged over 4 weeks

- In-house call typically no more frequently than every third night, when averaged

Individual specialties or programs may have additional restrictions or local policies.

2. Do shorter work hours always improve patient safety?

Not necessarily. The relationship between work hours and Patient Safety is complex. While severe sleep deprivation is clearly associated with increased error risk, some studies of reduced hours have shown:

- More handoffs, which can introduce communication errors

- Reduced continuity of care

- Mixed or minimal changes in overall error rates

The safest systems typically combine reasonable duty hours, robust handoff practices, good supervision, and a culture of safety, rather than focusing on hours alone.

3. How can I recognize signs of burnout during residency?

Common signs of burnout include:

- Emotional exhaustion, feeling “drained” most days

- Cynicism or detachment from patients or colleagues

- Reduced sense of accomplishment or growing self-doubt

- Irritability, changes in sleep or appetite, or increased reliance on substances

- Loss of interest in activities you previously enjoyed

If you notice these signs persistently, reach out early—to a mentor, trusted colleague, counselor, or your program’s wellness resources.

4. What should I do if my duty hours consistently exceed ACGME limits?

If your work hours frequently exceed guidelines:

- Accurately log your hours in your program’s tracking system

- Discuss the pattern with your chief residents or program director

- Bring specific examples (e.g., particular rotations or services where limits are consistently exceeded)

- If concerns persist, you can contact your Graduate Medical Education (GME) office or use anonymous reporting mechanisms

- In extreme cases, residents may report to the ACGME directly, though many issues can be addressed at the program or institutional level first

Responsible reporting is not punitive—it is an important part of maintaining safe and sustainable training environments.

5. How can technology realistically improve residency training and reduce burnout?

Technology can support Residency Training when used thoughtfully:

- Clinical decision support can reduce cognitive load for routine dosing and guideline-based decisions

- Voice recognition and AI-assisted documentation can cut down on charting time

- Telehealth can streamline some follow-ups and educational visits

- Better-designed EMRs can reduce redundant clicks and documentation fatigue

However, poorly implemented systems can increase workload and frustration. Effective solutions require collaboration between clinicians, IT teams, and leadership, with continuous feedback from residents.

Residency work hours sit at the intersection of Medical Education, workforce sustainability, and Patient Safety. The current system is an improvement over the unregulated past, but it remains far from perfect. As a future or current resident, your voice—and your well-being—are critical inputs into how residency evolves. Sustainable training is not about doing less; it is about structuring the work so that you can learn deeply, care safely, and still have enough of yourself left to practice medicine for decades to come.