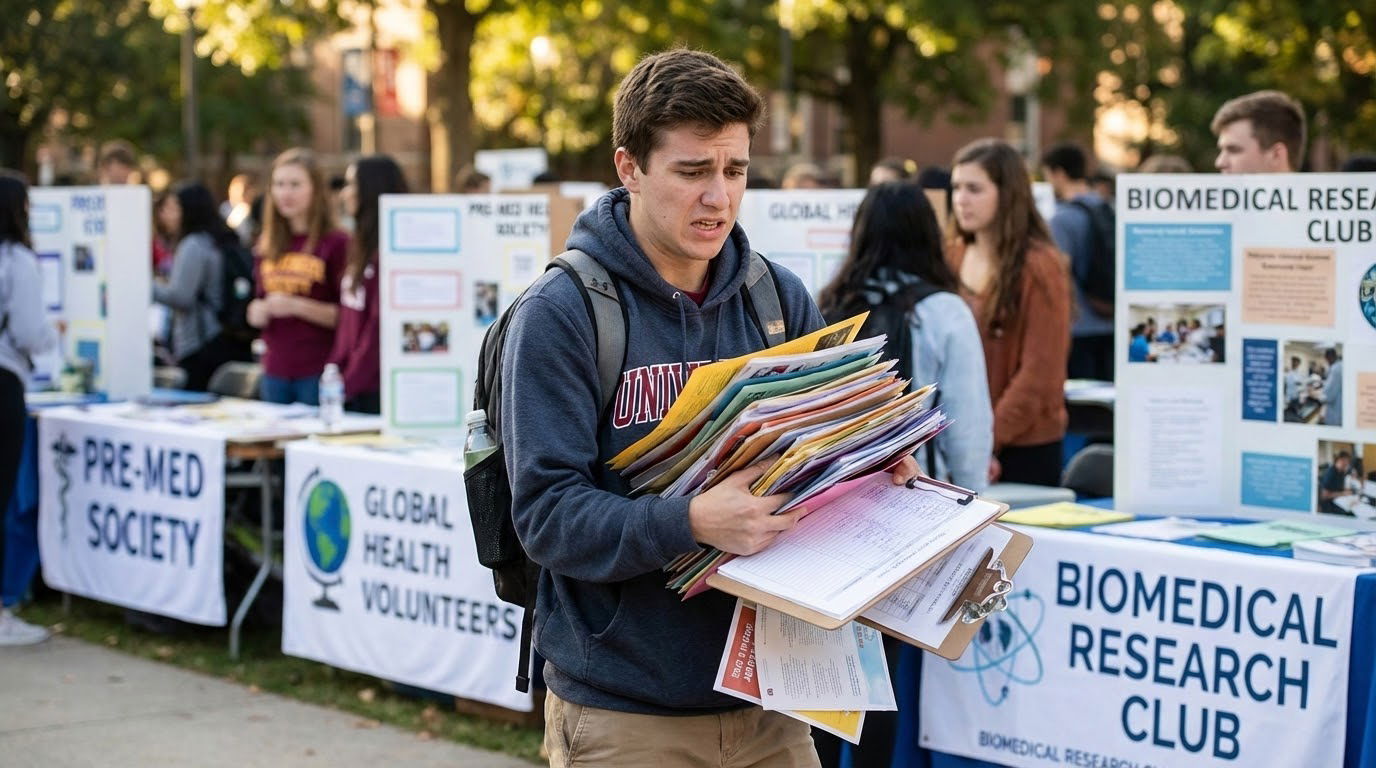

Stop joining every club “because it might look good on my med school application.” That mindset quietly ruins more applications than a low MCAT ever will.

The problem is not that you lack involvement. The problem is that you are drowning in it—and admissions committees can see the chaos clearly on your activities list.

You’re not being rewarded for how many logos you can cram onto your CV. You’re being evaluated on how you think, choose, commit, and grow. Overloading on student organizations is one of the fastest ways to signal the opposite.

Let’s walk through the mistakes that sabotage premeds and early medical students, and what to do instead before you burn yourself out and flatten your story into meaningless bullet points.

(See also: How to Turn Basic SNMA Membership Into High‑Impact Leadership in 6 Months for more details.)

The Biggest Lie: “More Clubs = Stronger Application”

This is the first trap.

Premeds hear:

- “You need to be well-rounded.”

- “You should be involved on campus.”

- “Join lots of things freshman year and see what sticks.”

So you sign up for:

- Pre-med society

- Red Cross Club

- Habitat for Humanity

- Global Brigades

- Biology Club

- Research journal club

- Three cultural orgs

- Shadowing program

- Hospital volunteering

- Peer mentoring

- Maybe a fraternity/sorority on top

On paper, it looks “busy.” In reality, it usually looks shallow.

How this backfires on your application

When you overload on student orgs, med schools often see:

Thin involvement

- Positions like “member” in 9 organizations with no clear impact.

- 1–2 hours per month sprinkled across random causes.

No coherent story

- Oncology volunteer, marine biology club, business fraternity, dance team, political campaign, and EMT… but nothing really deep or sustained.

- Hard to understand what actually matters to you.

Suspect motivation

- It reads as “I joined every premed-sounding thing I could find.”

- That screams box-checking, not authentic interest.

No leadership that actually means something

- “Co-chair of marketing committee” for a club that barely met.

- Titles without outcomes make committees roll their eyes.

A typical activities section from an over-involved student:

Member – Pre-Med Club

Member – AMSA

Volunteer – Hospital

Member – Global Health Org

Member – Red Cross Club

Member – Biology Club

Member – Neuroscience Society

Member – Cultural Org

Member – Public Health Interest Group

If you think that looks “impressive,” you’re already in dangerous territory.

Because here’s the truth: a single, well-developed, 3-year commitment with clear growth, reflection, and impact can carry more weight than 10 random memberships with no depth.

The Real Cost: Burnout, Mediocre Performance, and Vague Stories

The biggest danger isn’t just how it looks. It’s what it does to your life.

Mistake 1: Sacrificing your GPA for meaningless meetings

Common pattern:

- You attend 4 club meetings a week.

- You say yes to every event: blood drives, bake sales, guest lectures, tabling.

- You sign up for subcommittees because “leadership.”

Then:

- You’re behind on Anki/cards, readings, and problem sets.

- Your exam prep starts late every cycle.

- You’re perpetually tired.

Med schools will absolutely choose the student with:

- Fewer clubs

- A 3.8 with strong science grades

over the student with:

- 10 clubs

- A 3.3–3.4 pulled down by chronic overcommitment

You cannot “leadership your way out” of a damaged GPA.

Mistake 2: No time for genuine reflection

Overscheduled students often:

- Jump from one meeting to another.

- Rush from volunteer shifts straight into group projects.

- Have no mental margin to process what they’re experiencing.

Then, when it’s time for:

- Personal statement

- Work & Activities descriptions

- Secondary essays

They realize all their “experiences” blur together. Nothing stands out. They remember tasks, not transformation.

Reflection needs time and mental space. If your calendar has zero white space, your application will sound like a calendar—not a human.

Mistake 3: Doing everything at the “surface level”

A dangerous pattern looks like this:

- You attend a global health club meeting: discuss “health disparities.”

- You volunteer once at a health fair: hand out pamphlets.

- You do a one-week spring break medical mission: take photos, shadow loosely.

Then you write:

“I’m passionate about global health and serving the underserved.”

Admissions readers can tell when your “passion” is built on 12 total hours and an Instagram slideshow.

Depth comes from:

- Long-term involvement

- Increasing responsibility

- Real relationships with mentors and communities

Busy comes from signing up. Depth comes from staying.

How Admissions Committees Actually Read Your Activities

Do not make the mistake of assuming they skim and count.

Experienced readers:

- Scan for duration (how long)

- Note intensity (hours/week)

- Look for progression (growth over time)

- Identify themes (what you really care about)

- Watch for credibility (does this all hang together?)

What makes them suspicious?

Red flags they see constantly:

Endless laundry list of “member” roles

- 8–15 organizations, no one activity over 1–2 hours/week, little leadership.

Leadership titles without context

- “President,” “Director,” “Founder” — but small, inactive, or one-semester groups.

- Or 3–4 simultaneous “president” roles (they know that’s usually impossible to do well).

No anchoring experience

- Nothing clearly stands out as “this is what shaped this applicant.”

No sustained contact with vulnerable populations

- Tons of premed and academic clubs but minimal real clinical exposure or community work.

Overlapping timelines that defy realism

- Full-time coursework, heavy research, 15 hours/week of scribing, 10 hours/week of volunteering, multiple leadership positions — for years straight.

- They’ve been around; they know when hours are inflated.

What they actually want to see

They are far more impressed by:

1–3 anchor experiences that:

- Span multiple years

- Show increased responsibility or leadership

- Have clear outcomes you can describe

- Clearly shaped your understanding of medicine

A coherent narrative where:

- Your choices make sense together

- Your activities map onto your stated interests and values

- There is evidence of follow-through, not just initial enthusiasm

This is where joining every club kills you: it scatters your story into a pile of disconnected fragments.

Premeds vs. Early Med Students: Different Stage, Same Trap

Student org overload does not stop once you get into medical school. It just changes its costume.

For premeds

Common premed org mistakes:

- Joining every pre-health or medical mission club in sight.

- Being “on the email list” for 12 orgs and counting that as involvement.

- Taking on 3–4 officer roles junior/senior year to “make up for lost time.”

What that leads to:

- Sleep debt and rushing assignments.

- Mediocre MCAT prep because you’re “so busy.”

- Leadership that looks performative, not impactful.

For early medical students (M1/M2)

New environment, same trap:

- You feel pressure to:

- Run the interest group for your chosen specialty

- Join multiple specialty interest groups “just in case”

- Be on the class council

- Help plan the white coat ceremony, orientation, charity gala, etc.

Risks:

- Falling behind in anatomy or path because you “had to” attend 3 meetings and plan a lunch talk.

- Building a CV that says “I was on 7 committees” but can’t point to a single sustained project.

- Burning out before clerkships even start.

Med schools and residency programs are not impressed by:

“Member, Surgery Interest Group

Member, Pediatrics Interest Group

Member, Internal Medicine Interest Group

Member, EM Interest Group

Member, Cardiology Interest Group”

They’re impressed by:

“Co-leader, Student-Run Free Clinic – 2.5 years

Organized weekend coverage schedule, implemented new referral tracking system, expanded volunteer base from 45 to 80 students.”

One of those took showing up repeatedly and solving real problems. The other took five sign-up sheets and some free pizza.

The “Selective Yes” Strategy: How Many Orgs Is Too Many?

There’s no magic number. But there are clear danger zones.

A safer guideline for premeds

For most students, a sustainable structure looks like:

One core clinical/community experience

- Example: Hospital volunteering, hospice work, free clinic, EMT, crisis hotline.

- 2–4 hours/week, ideally for 1–3+ years.

One major campus or community commitment

- Example: Significant role in a cultural org, tutoring program, mentoring initiative, student government, or research project.

- This is often where leadership lives.

Optional smaller interests (1–3 light commitments)

- Example: Intramural sport, music group, religious org, hobby club.

- Low time, high enjoyment, minimal obligations.

Beyond that, every additional organization should be treated as suspicious until you prove it:

- Does it align with your values or long-term interests?

- Can you realistically show up consistently for at least a year?

- Will it add something distinct to your story, not just another line?

If the honest answer is “probably not,” skip it.

A safer guideline for early med students

For M1/M2:

School always comes first

- Your #1 “activity” is mastering the content so you can safely care for patients.

- Failing courses to be “super involved” is a catastrophic trade.

Choose:

- 1–2 student orgs you actually care about

- 1 meaningful project or leadership role (not in year 1 if stress is high)

Avoid:

- Joining a specialty interest group just because you might apply in that specialty.

- Multiple high-demand leadership roles simultaneously.

Residency programs care about:

- Grades/board performance

- Clinical performance

- LORs

- A small number of serious commitments

They don’t hand out interviews for “most lunch talks attended.”

The Dangerous Illusion of “Leadership Titles”

One of the most damaging misconceptions: “I need as many leadership titles as possible.”

Here’s how students torpedo themselves:

- They collect titles: president, vice president, chair, coordinator.

- They stretch themselves thin across 4–5 orgs.

- They do the bare minimum in each, or rely on others to cover for their absence.

- At application time, they list all the titles and hope the volume looks impressive.

Admissions readers aren’t grading the number of titles. They’re asking:

- What did you actually do?

- What problem did you solve?

- What changed because you were in this role?

- How did this change you?

A “Leadership” mistake example:

President, Health Outreach Club

Organized weekly meetings and coordinated volunteer activities for premed students interested in community outreach.

It sounds decent at first glance. Then the reader realizes it’s vague and interchangeable with 10,000 other descriptions.

Now compare with focused, deep involvement:

Volunteer → Coordinator → Co-Director, Student-Run Free Clinic

Began as a volunteer intake worker; later created a structured training manual to reduce errors in patient registration. As Co-Director, led a team of 15 volunteers, implemented a new scheduling system to reduce patient wait times by ~20 minutes, and partnered with the social work department to add resource referrals for housing and food insecurity.

One experience, three years, clear progression. That’s what you want.

Do not chase titles. Chase impact. Titles follow impact, not the other way around.

How to Fix Overload Without Nuking Your Application

If you’re reading this and recognizing yourself, do not try to fix it by going from 12 clubs to 0 overnight. That’s another mistake.

Here’s how to unwind the mess strategically.

Step 1: Map your current commitments honestly

Write down:

- Every organization you’re involved in

- Your role (member, officer, chair, etc.)

- Average hours/week (be honest, not aspirational)

- Duration so far (months/years)

- Whether it ties to clinical, community, academic, or personal interests

You’ll probably see:

- 1–2 things you care deeply about

- Several that are “fine, I guess”

- A few you forgot you were even in

Step 2: Rank them by real value, not appearance value

For each activity, ask:

If I invested more here, could this become:

- A leadership opportunity with real impact?

- A source of strong letters of recommendation?

- A deeply meaningful story I could write about?

Does this align with:

- My values?

- My long-term interests in medicine or my community?

Do I actually like being there, or do I just like what it “signals”?

The ones that check all three boxes? Those are your keepers.

Step 3: Identify what to gently exit

You’re looking for:

- Organizations where you’re just a name on a list

- Groups you attended for 1 semester and never really clicked with

- Roles where someone else is basically doing the work

You can step back by:

- Not running for another term.

- Transitioning early if appropriate and giving good notice.

- Staying on email lists but removing the mental pressure to attend.

A respectful exit now is better than:

- Ghosting meetings

- Missing events you committed to

- Underperforming in a visible role

That kind of behavior does get noticed, and occasionally, it does get mentioned to letter writers.

Step 4: Double down on your top 1–3

Now that you’ve made space, consciously:

- Show up consistently.

- Volunteer for meaningful tasks, especially the unglamorous ones.

- Look for real problems you can solve, not just positions you can hold.

- Ask mentors in those spaces how you can grow over time.

Depth looks like:

- Remaining with a hospice organization for 3 years

- Moving from general volunteer → trainer → coordinator

- Implementing a small but real change (better orientation materials, new scheduling workflow)

Shallow looks like:

- 3 different volunteer orgs, 10 hours each, no follow-up

- No idea what really changed because you were there

Red Flags You Should Take Seriously Right Now

If any of these are true for you, treat them as warning lights:

- You’re regularly sacrificing sleep to finish assignments after club events.

- Your grades or MCAT prep are slipping, and your first thought is “I can’t quit [club name], I’m president.”

- You can list 10 orgs instantly, but struggle to describe one experience that truly changed your perspective on medicine.

- You feel guilty saying no, so you say yes to everything.

- You’re anxious that dropping an org will “look bad” on your application.

Med schools will never reject you because you weren’t in enough clubs. They will reject you because:

- Your grades are weak.

- Your activities lack coherence and authenticity.

- Your essays feel generic and superficial.

The over-commitment you think is protecting you is often the exact thing putting you at risk.

Your Next Step (Do This Today)

Open your calendar and your resume right now. Circle the one activity you’d keep if you had to drop everything else.

Then write one paragraph (for yourself, not for an application) answering:

- Why does this matter to me more than the others?

- How have I changed because of this work?

- What could I do in the next 6–12 months to deepen my impact here?

If you can’t answer those questions for any of your organizations, that’s your sign: you’re collecting clubs, not building a story. Start fixing that today, before your application forces you to confront it under pressure.