Entering Medical School Without Panic: A Practical Guide to Facing the Challenges Ahead

Transforming anxiety into readiness is one of the most important transitions you’ll make as you start Medical School. Years of effort have gone into reaching this point, but the reality of starting can still feel overwhelming. The volume of content, the pace, and the emotional weight of training to become a physician are unlike anything most students have previously experienced.

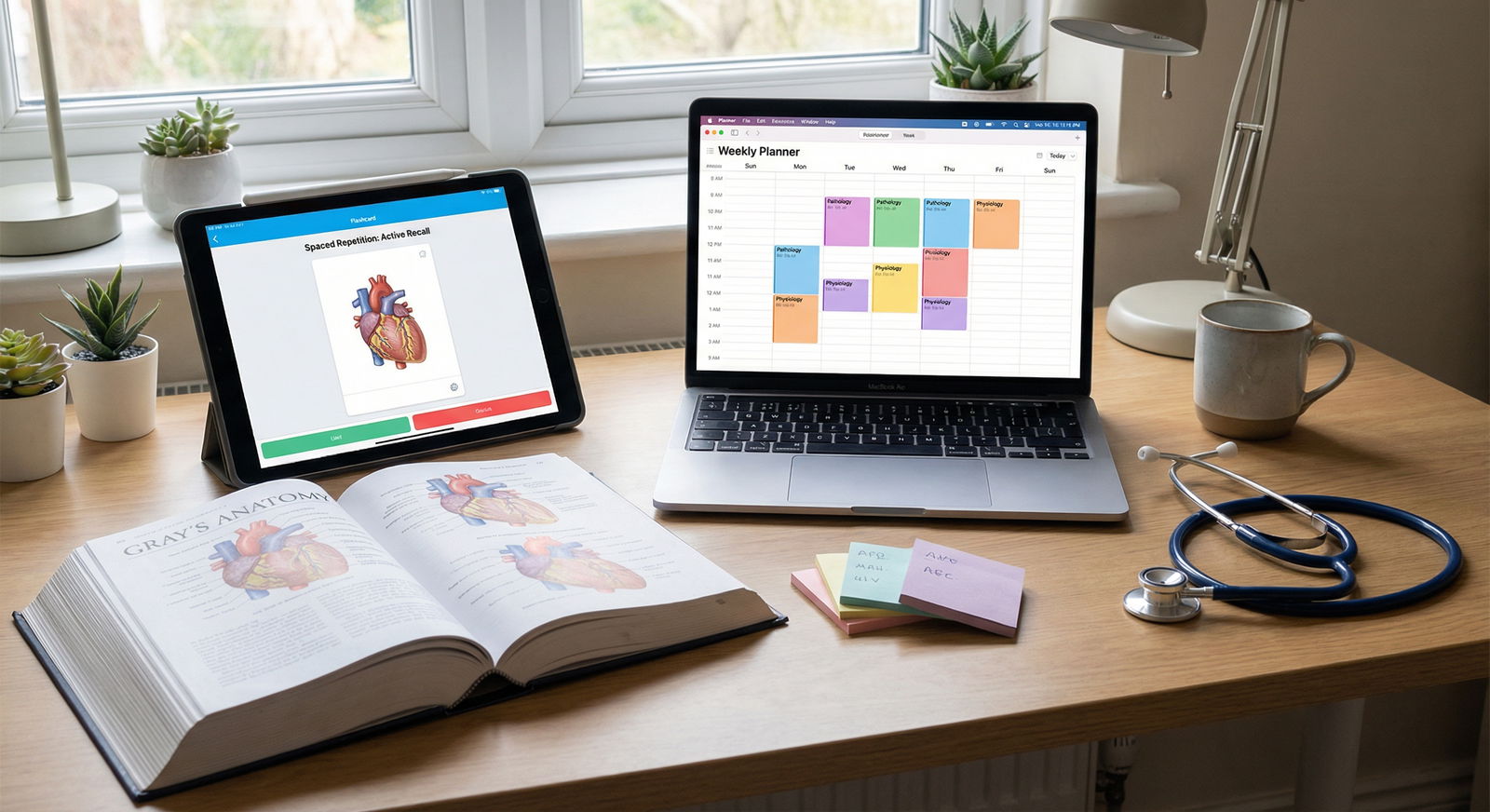

This guide is designed for incoming and early Medical School students who want concrete Study Tips, realistic expectations, and strategies for Time Management and Mental Health. The goal is not to eliminate stress—that’s impossible—but to give you structure, tools, and Student Resources so you can move from panic to preparation with intention and confidence.

Understanding the Reality of Medical School Life

Before you can plan effectively, you need a clear picture of what you’re stepping into. Many students intellectually “know” that Medical School will be hard, but the lived experience often feels different than expected.

The Intensity of the Curriculum and Learning Curve

Most Medical Schools follow a pre-clinical → clinical structure (often 2+2 years, though this can vary):

Pre-clinical years (usually Years 1–2):

- Heavy focus on foundational sciences: anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, pharmacology, pathology, microbiology, and more.

- Integration of early clinical skills: history taking, physical exams, communication skills, professionalism.

- Large blocks of lectures, labs, small groups (PBL/CBL), and independent learning.

- Fast pace: what took weeks to cover in college may be done in 1–2 days.

Clinical years (usually Years 3–4):

- Rotations in different specialties (internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, OB/GYN, psychiatry, etc.).

- Long hours on the wards, fluctuating schedules, and learning to function as part of a clinical team.

- Balancing patient care responsibilities with continued exam preparation (shelf exams, boards).

Many students describe the first year as “drinking from a fire hose.” The content is learnable—but not with the same casual approach that might have worked in undergraduate courses. Effective Time Management and active Study Tips become survival skills.

The Mental and Emotional Weight of Training

Medical School is intellectually demanding, but the emotional pressure is just as real:

- Constant evaluation – exams, OSCEs, practicals, clinical evaluations, professionalism check-ins.

- Imposter syndrome – feeling like you don’t belong, or that admissions made a mistake.

- Comparison culture – classmates who seem to understand everything, study all night, or always score higher.

Unchecked, these pressures can erode Mental Health and contribute to burnout, depression, or anxiety. Recognizing this early and treating your well-being as non-negotiable—not optional—is critical.

A Competitive Yet Collaborative Environment

You are now surrounded by high-achieving peers, many of whom were at the top of their previous classes. This can create:

- A sense of competition for grades, honors, research, and residency positions.

- A tendency to overwork to “keep up” or outpace others.

- Pressure to say “yes” to every opportunity to avoid falling behind.

At the same time, many schools emphasize teamwork and collaboration:

- Group learning (PBL/CBL, labs)

- Peer teaching and tutoring

- Student organizations and interest groups

Your job is to find a way to engage with others constructively—supporting and learning from your peers—without tying your self-worth to constant comparison.

Balancing Personal Life, Identity, and Training

You are more than a Medical School student. You may also be:

- A partner, parent, caregiver, or employee

- Someone with religious, cultural, or community commitments

- An athlete, artist, or person with other passions

Balancing personal life and academic responsibilities is an ongoing challenge:

- Social plans may need to be more intentional and scheduled in advance.

- Relationships (romantic or otherwise) may be strained by time constraints and stress.

- Maintaining hobbies can feel “selfish,” even though they support long-term performance and Mental Health.

Surviving first year means accepting that you can’t do everything—but you must protect the relationships and activities that sustain you.

Laying the Foundation: Organizational Systems and Essential Supplies

Once you understand the landscape, the next step is building systems that work for you rather than against you.

Organize Your Physical and Digital Resources

Physical setup:

- Create a primary study space

- Quiet, well-lit, comfortable chair, minimal clutter.

- External monitor and keyboard if you study from a laptop for long periods.

- Essential tools:

- Reliable laptop or tablet (many schools provide lecture notes electronically).

- A few high-quality notebooks or a digital note-taking system (e.g., OneNote, Notability, GoodNotes).

- Comfortable noise-cancelling headphones or earplugs if needed.

Digital organization:

- Centralize course materials:

- Create folders by block/course (e.g., “Foundations,” “Cardio,” “Neuro”).

- Subfolders: “Lectures,” “Labs,” “Practice Questions,” “Notes.”

- Use a calendar system:

- Sync your school calendar (lectures, exams, labs) to Google Calendar or Outlook.

- Color-code class, exams, personal commitments, and clinical skills sessions.

- Task management:

- Use apps like Notion, Trello, Todoist, or simple lists to track:

- Upcoming quizzes/exams

- Assignments

- Long-term goals (board prep, research)

- Use apps like Notion, Trello, Todoist, or simple lists to track:

A clear, visible system reduces decision fatigue and last-minute panic. You don’t want to waste mental energy figuring out what to study every day.

Build a Weekly Framework Before Classes Start

Instead of reacting week by week, proactively map out your baseline schedule:

- Block out fixed commitments first:

- Mandatory lectures/labs

- Small group sessions

- Clinical skills sessions

- Add self-care and non-negotiables:

- Sleep (aim for 7–8 hours)

- Exercise (3–5 sessions/week, even short ones)

- Meals and grocery time

- Religious or family commitments

- Schedule study blocks:

- 2–4 focused blocks per day (60–90 minutes each).

- Include review time (e.g., 1–2 hours daily for spaced repetition or Anki).

- Leave “buffer zones”:

- Free blocks that can flex for extra studying, rest, or unexpected tasks.

Your schedule will evolve as you learn how long tasks take, but having a framework makes adjustments easier and lowers anxiety.

Studying Smarter: Evidence-Based Medical School Study Tips

Learning in Medical School is different in both quantity and type of information. Passive methods (re-reading, highlighting, listening) are insufficient on their own.

Active Learning as Your Default

Evidence-based strategies that work particularly well in Medical School:

Spaced repetition:

- Revisit material at increasing intervals to strengthen long-term retention.

- Tools: Anki, Quizlet (with scheduled review), or similar spaced repetition platforms.

- Make smaller, high-yield cards (one fact or concept per card).

Retrieval practice:

- Regularly test yourself without looking at notes.

- Use:

- Practice questions (from commercial q-banks or school-provided banks)

- Closed-book recall (e.g., “What are the side effects of this drug?”)

- Whiteboard or scratch paper “brain dumps” of pathways or differentials.

Elaboration and teaching others:

- Explain a concept out loud to a classmate, or to yourself.

- Use Feynman technique: teach it in simple, clear language as if to a non-medical friend.

- Peer teaching groups can double as social support.

Interleaving:

- Mix topics (e.g., cardio physiology questions interspersed with pharm) instead of block-studying only one subject.

- This improves flexible use of knowledge in clinical contexts.

Designing a Sustainable Study Schedule

An example of a typical weekday during the first year might look like:

- Morning:

- 8:00–12:00 – Lectures and/or labs

- Afternoon:

- 1:00–2:00 – Break, lunch, short walk

- 2:00–3:30 – Review same-day lectures using active methods (Anki, practice questions)

- 3:30–3:45 – Short break

- 3:45–5:15 – Work on cumulative review (older topics)

- Evening:

- 5:30–6:30 – Exercise/dinner

- 7:00–8:30 – Light review or group study, if needed

- 8:30 onwards – Wind down, non-academic activities, sleep prep

Key principles:

- Front-load the week: aim to stay on top of lectures early so you’re not buried before an exam.

- Avoid perfectionism: “done and reviewed” beats “perfect but incomplete.”

- Reflect weekly: what worked, what didn’t, and what adjustments you need.

Gradual Exam Preparation (Not Just Pre-Exam Marathons)

Rather than cramming in the final week:

- Start board-style Q-banks once you have basic familiarity with a system (e.g., after a few weeks of cardio).

- Integrate short question blocks (10–20 questions) a few times per week.

- Create a “missed questions” notebook or Anki deck to track recurring weaknesses.

This approach not only strengthens content mastery but also reduces test anxiety by making exams feel like an extension of your normal routine.

People Matter: Mentorship, Peer Support, and Collaboration

You are not expected to figure out Medical School alone. Learning to ask for help early is a strength, not a weakness.

Seeking Guidance and Building a Mentorship Network

Types of mentors and how they can help:

Upperclassmen:

- Practical advice on courses, exams, and which resources are high-yield at your school.

- Tips on balancing boards, extracurriculars, and personal life.

- Strategies for specific faculty expectations or exam formats.

Faculty mentors/advisors:

- Career direction (specialty choice, research opportunities).

- Professional development and letters of recommendation.

- Perspective when dealing with setbacks or failures.

Peer mentors (near-peers):

- Students 1–2 years ahead in structured mentorship programs.

- Easier to access and often more available for day-to-day questions.

How to get started:

- Attend orientation events and mentorship mixers.

- Join interest groups (e.g., internal medicine club, surgery interest group).

- Send a brief, respectful email asking for a 20–30 minute meeting to ask about their path and advice.

Smart Use of Study Groups and Collaboration

Study groups can be powerful—if used correctly.

When study groups help:

- Clarifying difficult concepts through discussion.

- Practicing clinical reasoning or case-based questions.

- Teaching and reinforcing each other’s understanding.

- Providing accountability and social support.

When to be cautious:

- Group devolves into venting or socializing when you need focused study.

- Time is spent rewriting notes together instead of doing questions or active recall.

- You leave more confused or anxious than when you arrived.

Tips for effective group study:

- Keep groups small (3–5 people).

- Set an agenda and time limit (e.g., 6–8 PM, cardio path questions only).

- Use questions, cases, or whiteboard sessions, not just reading slides together.

- Solo study is still essential; use groups to supplement, not replace it.

Protecting Your Mental Health and Well-Being

High performance in Medical School is impossible to sustain without protecting your Mental Health. Burnout is common but not inevitable if you plan proactively.

Recognizing Early Signs of Strain

Watch for:

- Persistent difficulty sleeping, even when exhausted.

- Loss of interest in previously enjoyable activities.

- Feeling numb, detached, or chronically irritable.

- Significant changes in appetite, energy, or concentration.

- Thoughts like “I’ll never catch up,” “I don’t belong here,” or “Everyone else is fine but me.”

These are signals—not character flaws. Respond early rather than waiting for a crisis.

Building a Wellness Routine That Actually Fits Medical School

Core practices that are realistic and effective:

Sleep as a priority, not a luxury:

- Aim for 7–8 hours most nights.

- Maintain a consistent sleep-wake time when possible.

- Avoid all-night study sessions; they usually harm long-term retention and performance.

Exercise as stress management:

- 20–30 minutes, 3–5 times per week:

- Walks between lectures

- Short strength workouts

- Yoga or stretching at home

- Think of this as “brain maintenance,” not optional fitness.

- 20–30 minutes, 3–5 times per week:

Mindfulness and grounding:

- 5–10 minutes a day of:

- Breathing exercises

- Guided meditation apps

- Brief body scans or grounding techniques before exams

- Helps reduce anxiety and improve focus.

- 5–10 minutes a day of:

Scheduled non-academic time:

- Weekly blocks for family, friends, hobbies, or faith practices.

- Treat these appointments with the same respect as lectures.

Using Available Student Resources Without Hesitation

Almost every Medical School provides:

- Student counseling or psychotherapy services

- Crisis support contacts

- Wellness offices or deans

- Peer support or affinity groups (e.g., for first-generation students, underrepresented students, parents in medicine)

Reaching out does not jeopardize your standing in school. In fact, appropriately documented support can sometimes lead to accommodations that help you perform at your best (extra test time, reduced load after a crisis, etc.).

Mastering Time Management and Mindset for Long-Term Success

Beyond day-to-day studying, surviving Medical School requires a sustainable approach to your time and your thoughts.

Time Management Strategies That Work in Medical School

A few practical tools and approaches:

The “Big 3” daily rule:

- Identify your top three academic priorities for the day.

- Finish these before less important tasks (e.g., inbox, social media, deep-cleaning your notes).

Time blocking:

- Assign tasks to specific time windows, not endlessly expanding to-do lists.

- Include mini-deadlines (e.g., “Finish anatomy review by 4 PM”).

Batching similar tasks:

- Do all emails at once.

- Group Anki reviews into set blocks.

- Batch administrative tasks (forms, scheduling, financial aid) into a weekly block.

Learning to say “no”:

- You cannot join every club, every research project, and every social event.

- A useful test: “Will this matter in 1–2 years for my growth or well-being?”

- Politely decline or delay opportunities that don’t align with your current bandwidth.

Embracing a Growth Mindset and Learning from Setbacks

You will miss questions. You might underperform on an exam. You may feel “behind” at times. None of these mean you are not cut out for medicine.

A growth mindset approach:

View failures as data, not verdicts:

- After a poor exam:

- What content was weak?

- Did I rely too much on passive studying?

- Was my sleep/exercise inadequate that week?

- Create an adjustment plan; do not just “try harder” in the same way.

- After a poor exam:

Actively seek and use feedback:

- Ask faculty, mentors, or peers:

- “What’s one thing I could do differently next time?”

- Use OSCE or clinical feedback sessions as a roadmap, not a criticism.

- Ask faculty, mentors, or peers:

Normalize the struggle:

- Most physicians can recount times they barely passed an exam, failed a test, or questioned their abilities.

- Remind yourself: growth in medicine is non-linear, and resilience is built over time.

High-Yield External Student Resources to Consider

Your school will provide core materials, but many students also benefit from external resources. These should support—not replace—your required coursework.

Online Courses and Video Platforms

Foundational science reinforcement:

- Khan Academy, Coursera, edX: Useful for reviewing physiology, biochemistry, statistics.

- Choose targeted modules relevant to your current block.

Medical Education Platforms:

- Osmosis, Lecturio, Boards & Beyond, Sketchy, Pathoma:

- Great for visual learners and for integrating concepts.

- Use these selectively alongside your curriculum, not as endless passive viewing.

- Osmosis, Lecturio, Boards & Beyond, Sketchy, Pathoma:

Books, Question Banks, and Study Guides

High-yield reference books:

- “First Aid for the USMLE Step 1” (even if your school is pass/fail, this can serve as an organized content outline).

- “Rapid Review Pathology” or similar for later systems blocks.

Question banks:

- School-provided or commercial q-banks (e.g., UWorld, AMBOSS for later stages).

- Start light and increase usage as your foundation strengthens.

Less Formal but Helpful: Podcasts, Blogs, and Social Media

Medical education podcasts:

- Board review, clinical reasoning, specialty overviews.

- Useful during commutes or workouts.

Blogs and student narratives:

- Help normalize your experiences and provide realistic stories of struggle and success.

Social media (with caution):

- Can provide community and tips.

- Avoid constant comparison; remember people often share highlights, not full context.

Use these tools intentionally, not as procrastination disguised as productivity.

Frequently Asked Questions: Surviving First Year and Beyond

1. What is the biggest challenge in Medical School?

For most students, the biggest challenge is managing the combination of:

- Heavy academic workload

- Emotional ups and downs

- Time pressure and fatigue

- Pressure to perform and plan for residency

It’s not usually one exam or course, but the cumulative demand over time. A structured system, realistic expectations, and early attention to Mental Health make these challenges manageable.

2. How can I manage my time more effectively during the first year?

Effective Time Management in Medical School includes:

- Using a digital calendar and planner to map out classes, exams, and study blocks.

- Prioritizing 2–3 key tasks per day instead of unrealistic to-do lists.

- Building in daily review (e.g., Anki, practice questions) rather than relying on last-minute cramming.

- Protecting sleep and exercise time as part of your schedule, not afterthoughts.

- Regularly reflecting (weekly) to adjust your approach if something isn’t working.

3. What Mental Health resources are typically available to Medical Students?

Most Medical Schools provide:

- Free or low-cost counseling and psychological services

- Crisis lines and on-call support for urgent issues

- Wellness or student affairs offices dedicated to Student Resources

- Support or affinity groups for specific communities (e.g., first-generation, LGBTQ+, underrepresented in medicine)

You can usually learn about these during orientation, via your student handbook, or on the school website. Reaching out early, even for “minor” concerns, can prevent bigger problems later.

4. Is it better to study alone or in groups in Medical School?

Both approaches are valuable, and the ideal balance depends on your learning style:

- Study alone for:

- Initial content absorption

- Focused Anki or question bank sessions

- Deep concentration tasks

- Study in groups for:

- Clarifying difficult concepts

- Practicing clinical reasoning and oral explanations

- Accountability and social support

Many students use a hybrid model: most of the week solo, with 1–2 structured group sessions for questions and discussion.

5. What is the best way to stay organized and reduce panic across the semester?

To stay organized and move from panic to prepared:

- Set up clear digital and physical organization systems before courses intensify.

- Maintain a weekly overview of deadlines, exams, and major tasks.

- Use checklists and time blocking so you always know your next action.

- Do small, consistent review sessions instead of large, last-minute study marathons.

- Regularly reassess your systems and adjust—organization is a dynamic process, not a one-time setup.

Entering Medical School is a major transition, and feeling anxious at the start is completely normal. With practical Study Tips, intentional Time Management, and a commitment to your Mental Health, you can navigate the rigor of this phase and emerge not only as a competent future physician, but as a more resilient and self-aware person. You do not have to be perfect; you only need to keep learning, adjusting, and moving forward.