Understanding Your Unique Position as a Non‑US Citizen IMG in Preliminary Medicine

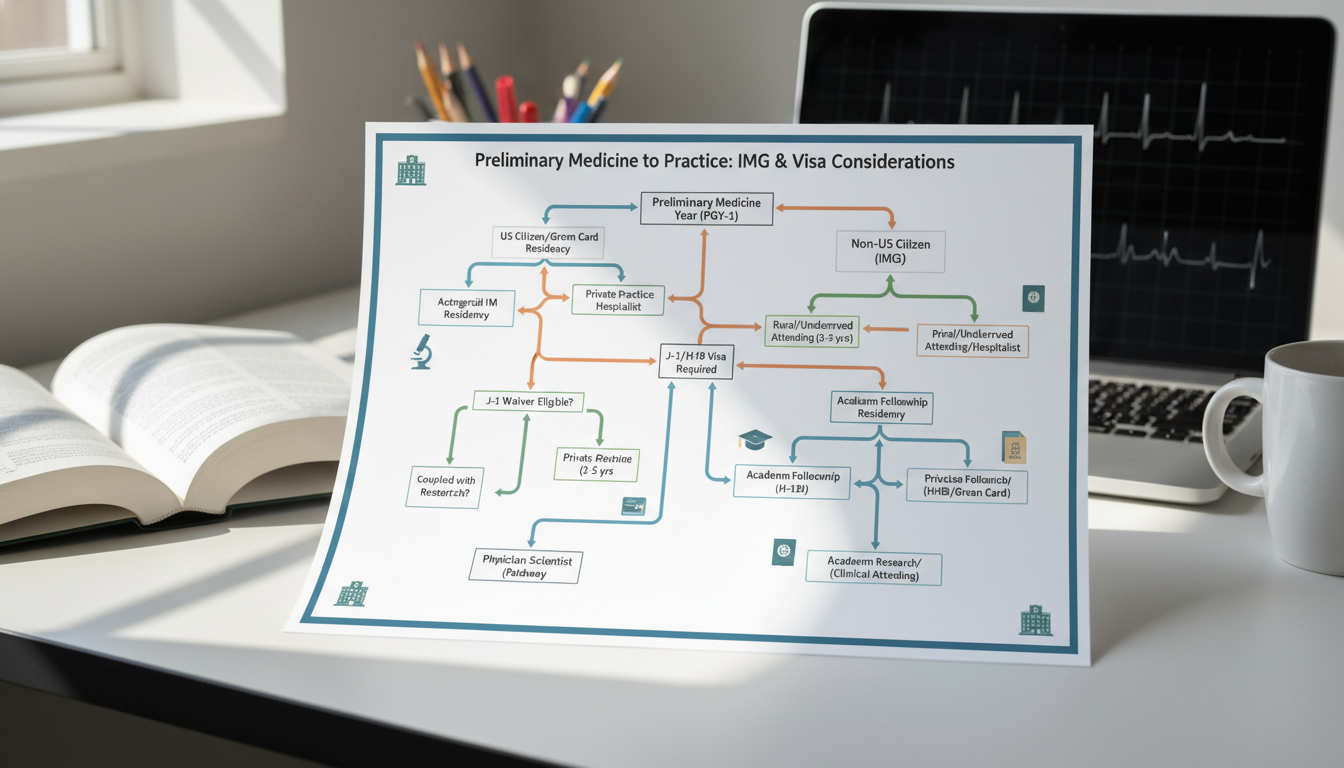

As a non-US citizen IMG completing or considering a preliminary medicine year (prelim IM), you are in a very specific—and often misunderstood—career position. You are not only navigating the usual questions of choosing a career path in medicine, but also dealing with:

- Visa sponsorship and timing

- The temporary nature of a prelim year

- The need to match (or rematch) into a categorical position or advanced specialty

- Limited time to build a CV that supports either academic medicine career goals or a future in private practice

This article focuses on how the academic vs private practice decision applies to you, specifically as a non-US citizen IMG in Preliminary Medicine, and how you can use your prelim year strategically, even before you have a categorical slot secured.

Key themes we will cover:

- What “academic medicine” and “private practice” actually look like in real life

- How visa status and being a foreign national medical graduate influence your options

- Common pathways from prelim IM to long‑term academic or private careers

- Concrete steps during your prelim year to keep both doors open

- How to think about salary, lifestyle, research, teaching, and long‑term stability

Academic Medicine vs Private Practice: What Do They Really Mean?

Before you decide anything, it helps to be very clear on the definitions. Many applicants use “academic” and “private practice” as labels without understanding the day-to-day work.

Academic Medicine Career: Core Features

In the US, an academic medicine career usually means working primarily in:

- A university hospital or

- A teaching hospital affiliated with a medical school

You are typically employed by:

- A university (e.g., “Assistant Professor of Medicine”)

- A faculty group practice that is linked to a university/teaching hospital

Main components of an academic role:

Clinical care

- You see patients in the hospital (ward/ICU) and/or clinics.

- Case complexity is often higher—tertiary or quaternary referral cases.

- You frequently work with residents and medical students at the bedside.

Teaching

- Teaching on rounds

- Giving noon conferences or small-group sessions

- Supervising medical students and residents in clinic

- Being involved in simulation, OSCEs, or other educational activities

Research and scholarship (varies by institution/track)

- Quality improvement (QI) projects

- Clinical research (chart reviews, prospective studies, trials)

- Education research (curriculum development, teaching methods)

- Publishing papers, writing guidelines, presenting at conferences

Administrative and leadership work

- Committee membership (e.g., residency program committee, QI committee)

- Potential leadership roles (program director, clerkship director, section chief)

Pros of academic medicine:

- Structured environment for teaching and learning

- Easier access to research mentorship, conferences, and academic resources

- Clear academic titles and promotion pathways

- Usually better for those who want to stay connected to training programs

- Stronger institutional experience with J‑1 waiver and H‑1B processes

Cons of academic medicine:

- Typically lower salary than high‑earning private practice roles, especially early on

- More meetings, institutional bureaucracy, and pressure to “publish or perish” at some centers

- Less control over schedule and clinical load in junior positions

- Opportunities can be competitive for a foreign national medical graduate without US-based research or strong letters

Private Practice: Core Features

Private practice can mean many different organizational structures:

- Small independent group (e.g., 5–15 internists)

- Large multi-specialty group (sometimes owned by physicians, sometimes by a hospital)

- Direct employment by a hospital system but with primarily revenue-driven practice

- Concierge or boutique models (less common for newly trained IMGs)

Main components of private practice:

Clinical care as the main focus

- Most of your time is spent seeing patients.

- You might do outpatient primary care, inpatient hospitalist work, or a mix.

- Teaching and research are limited or optional.

Business and productivity orientation

- Productivity measured in RVUs, number of patient visits, or procedures.

- Compensation often tied directly to how much revenue you generate.

- You may or may not be involved in practice management decisions (billing, hiring staff, etc.).

Limited teaching and research

- Some private practitioners teach students or residents occasionally, but it’s not central.

- Research is rare unless you are in a hybrid model or partner with academic institutions.

Pros of private practice:

- Often higher earning potential sooner

- Potential for more control over your practice style and working hours (depending on model)

- Less academic pressure for publications and promotion

- For some, a more predictable, business-like environment

Cons of private practice:

- Less structured support for visas and immigration in many small groups

- Fewer formal opportunities for teaching and research

- You may feel professionally isolated if you enjoy an academic environment

- Business risk (especially in small or independent practices)

How Being a Non‑US Citizen IMG Changes the Equation

As a non-US citizen IMG, your decision is not purely about lifestyle or prestige. Immigration and structural barriers matter enormously. Your preliminary medicine year adds yet another layer.

Visa Considerations: J‑1 vs H‑1B and Waivers

Most foreign national medical graduates are on:

- J‑1 visa (ECFMG sponsored) or

- H‑1B visa (employer sponsored)

Each has implications for academic vs private practice.

If you are on a J‑1 visa

- After residency/fellowship, you must either:

- Return to your home country for 2 years, or

- Obtain a J‑1 waiver job for 3 years in the US (often in underserved areas)

How this links to academic vs private:

Many J‑1 waiver positions are:

- Community-based or rural

- Hospital-employed internal medicine or hospitalist roles

- Sometimes nominally “academic” but with minimal teaching/research

Some academic centers offer J‑1 waiver jobs, especially:

- University-affiliated hospitals in underserved regions

- Hybrid academic/community roles

As a prelim resident, you won’t jump directly from prelim IM to a J‑1 waiver job—you first need a categorical or advanced residency completion. But understanding where waiver jobs exist can inform your strategy:

- Academic path: Choose fellowships/specialties that have known J‑1 waiver opportunities (e.g., hospitalist medicine, some subspecialties in underserved states).

- Private practice path: Plan for a waiver job in a community or hospital-employed group, often with heavier clinical loads.

If you are on an H‑1B visa

- H‑1B can be more straightforward for long‑term US practice, but:

- Not all programs sponsor H‑1B visas.

- Private practices may be hesitant to sponsor or may lack HR expertise.

- Some academic centers are more experienced with H‑1B policies and cap‑exempt positions.

Most common pattern for H‑1B IMGs:

- H‑1B for categorical residency (and sometimes for fellowship)

- Transition to an academic, hospital-employed, or large group job that continues H‑1B or pursues a green card

- Smaller private practices might be a second step once you have permanent residency

How the Preliminary Medicine Year Specifically Complicates Things

As a prelim IM resident, you:

- Have only one guaranteed year of internal medicine training

- Still need to:

- Transition into a categorical IM position (PGY‑2 or PGY‑1 restart), or

- Enter an advanced specialty that begins after prelim (e.g., Neurology, Anesthesiology, Radiology, etc.)

This influences your academic vs private practice thoughts in several ways:

You are not choosing your final practice type yet.

You are deciding:- What specialty and residency track you can realistically pursue

- Where you can build the kind of CV (clinical, research, teaching) that fits your future goals

Your prelim year is your “audition.”

- Performance, evaluations, and networking will strongly affect your ability to:

- Transfer to categorical IM at your institution

- Secure strong letters for another program or for fellowship

- Academic centers may be more responsive to a prelim resident who shows early academic interest.

- Performance, evaluations, and networking will strongly affect your ability to:

You must think two steps ahead.

- For academic medicine: “Which residency/fellowship will give me the best foundation for research/teaching?”

- For private practice: “Which training pathway leads to in-demand, employable skills in the community (e.g., hospitalist, outpatient primary care, or high‑demand subspecialty)?”

Academic Medicine Pathways for Non‑US Citizen IMGs in Preliminary Medicine

If your long‑term goal is an academic medicine career, you can absolutely get there as a non-US citizen IMG, even starting from a preliminary medicine year—but you must be intentional.

Step 1: Use Your Prelim Year to Build an Academic Profile

Even though it’s just one year, you can still:

Engage in research or QI projects early.

- Ask your program director (PD) or chief resident:

“Are there ongoing projects I can contribute to during my prelim year?” - Focus on feasible work:

- Retrospective chart reviews

- Case reports or case series

- QI initiatives (sepsis order sets, readmission reduction, etc.)

- Target abstracts and posters at local or national meetings.

- Ask your program director (PD) or chief resident:

Demonstrate enthusiasm for teaching.

- Offer to help with:

- Student teaching activities

- Morning reports (presenting cases)

- Informal tutoring of junior students

- Let your faculty know you are interested in teaching as a core career goal.

- Offer to help with:

Network with academic mentors.

- Identify at least two faculty mentors:

- One clinically oriented (e.g., hospitalist, outpatient IM attending)

- One research/academic oriented (e.g., clinician‑investigator, educator)

- Ask them honestly:

- “Given my non-US citizen IMG status and prelim year, how can I maximize chances for categorical or fellowship positions that align with academic medicine?”

- Identify at least two faculty mentors:

Document and showcase your work.

- Maintain an updated CV with:

- Presentations (even local)

- Quality improvement projects

- Teaching activities

- This will strengthen your application for:

- Categorical IM transfer

- Advanced specialties (e.g., Neurology, Radiation Oncology, etc.)

- Future academic jobs

- Maintain an updated CV with:

Step 2: Target Categorical and Fellowship Paths that Fit Academic Career Goals

For most IMGs, academic medicine is more accessible through:

- Internal Medicine (categorical) → academic hospitalist or subspecialist

- Advanced specialty with strong academic culture (e.g., Neurology, Radiology, Anesthesiology, etc.)

During or right after your prelim year:

Apply broadly to categorical or advanced positions in institutions with:

- Active residency/fellowship programs

- Visible research output

- History of hiring IMGs on visas

Choose programs that value teaching and scholarship.

Indicators:- Regular resident conferences, journal clubs

- Protected academic time for residents

- Faculty with published work who welcome student/resident co‑authors

Think about subspecialty fellowship early (if aiming academic).

- Cardiology, Pulmonology/Critical Care, Hematology/Oncology, Gastroenterology, Infectious Diseases, Nephrology, etc.

- Fellowship plus academic focus (e.g., outcomes research, epidemiology, medical education) can create strong academic roles later.

Step 3: Long-Term Academic Job Planning as a Non‑US Citizen

Once in categorical residency or fellowship:

- Leverage visa-savvy institutions.

- Target academic centers with:

- GME offices familiar with J‑1 waiver positions (if J‑1)

- H‑1B and green card sponsorship track records (if H‑1B)

- Target academic centers with:

- Craft a niche.

- QI leader, educator (resident clinic director, simulation expert), or subspecialist with research focus.

- Having a niche makes you more attractive as faculty, regardless of IMG status.

Example pathway:

Non-US citizen IMG → Prelim IM year at community teaching hospital → Transfers into categorical IM at a university-affiliated program → Completes QI projects and publishes a few case reports → Matched into Pulmonary/Critical Care fellowship at large academic center → Takes academic hospitalist/ICU role with appointment as Assistant Professor → Later promoted while obtaining J‑1 waiver in a university-affiliated underserved region.

Private Practice vs Academic: Practical Differences That Matter to You

When choosing a career path in medicine, especially as a foreign national medical graduate, you should look at concrete realities, not just titles.

1. Salary and Financial Trajectory

Academic medicine:

- Base salary is typically lower than high-productivity private practice.

- You may receive:

- Academic stipends

- Extra pay for call or procedures

- Compensation for administrative roles

- Academic environments may support loan repayment programs (less relevant if trained abroad but may apply if you have US loans).

Private practice:

- More likely to offer:

- Higher starting salary or income potential

- Productivity bonuses

- Partnership tracks (in some groups)

- You may, however, face:

- Variable income based on productivity

- Less transparency initially about billing and overhead

- More likely to offer:

For non-US citizen IMGs, a high early salary may be less important than:

- Visa stability

- First job security

- Whether the employer has experience with IMG hires

2. Lifestyle and Workload

Academic medicine:

- Variable; some academic hospitalist jobs are intense (nights/weekends, high acuity).

- May have more predictable schedules if you are in a defined service (e.g., 7‑on 7‑off).

- Teaching and conferences can lengthen the day but also add professional fulfillment.

Private practice:

- Workload depends on:

- Outpatient vs inpatient emphasis

- Call responsibilities

- Practice size (larger groups may share call more widely).

- Busy private clinics may schedule short visit times (e.g., 15 minutes per patient) to maximize productivity.

- Workload depends on:

As a non-US citizen IMG, you also need to consider:

- Ability to travel home (vacation flexibility)

- Childcare/support structure if relocating to smaller communities

- Burnout risk if you feel disconnected from academic or peer support

3. Professional Identity and Growth

Academic:

- Clear identity as “educator,” “researcher,” or “subspecialist.”

- Regular exposure to new evidence, conferences, and trainees.

- Promotion ladder: Assistant → Associate → Full Professor (with varying expectations).

Private practice:

- Identity is more clinical and business-focused: “My patients, my practice”.

- Growth is measured in:

- Patient panel size

- Partnership

- Leadership roles in hospital committees or networks

Many IMGs find hybrid roles that blur these lines:

- Hospital-employed positions with some resident teaching

- Community-based practices that host students from nearby schools

- Academic-affiliated groups that function like private practice clinically

Thinking too rigidly (academic vs private as a binary) can be limiting; recognize that there is a spectrum.

Strategic Recommendations for Prelim IM Non‑US Citizen IMGs

Below are tailored, actionable steps so you can keep both academic medicine career and private practice options open while navigating the unique constraints of a preliminary medicine year.

1. Clarify Your Long-Term Priorities (Even if They Change)

Ask yourself:

- Do I get more satisfaction from:

- Teaching and discussing complex cases?

- Running an efficient clinic and building long-term patient relationships?

- Do I want:

- A heavily research-oriented career?

- Primarily clinical practice with some teaching?

- A purely clinical, business-focused practice?

Rank your values in order (e.g., visa security, teaching, salary, geography, family needs). This will guide decisions.

2. Maximize Your Prelim Year Visibility and Performance

- Be reliable and hardworking; your reputation travels quickly.

- Communicate your career interests to:

- Program Director

- Associate PDs

- Key faculty

- Proactively ask:

- “Are there categorical slots that might open?”

- “Would you be open to supporting me with a strong letter if I apply for categorical/advanced positions?”

Even if you’re unsure about academic vs private in the future, you still want the strongest possible training foundation now.

3. Build a CV That Serves Both Paths

Activities during prelim IM that help both academic and private careers:

- Strong clinical evaluations and letters – essential everywhere

- Quality improvement – highly valued in both academic and private hospitals

- Teaching experiences – show leadership and communication skills

- Participation in hospital committees – demonstrates professionalism and systems thinking

You don’t need a full research portfolio to succeed in private practice, but having one never hurts; it broadens your options.

4. Understand the Market You Will Enter

Look at job ads and talk to senior residents/fellows:

- Which specialties are hiring IMGs with visas in academic settings?

- Which geographic areas are IMG‑friendly for private practice or hospitalist roles?

- Are there J‑1 waiver or H‑1B-friendly employers that align with your goals?

Resources:

- State health departments with J‑1 waiver program lists

- Institutional GME or international office

- Senior IMGs at your institution who have recently transitioned to jobs

5. Avoid Common Pitfalls for Non‑US Citizen IMGs in Prelim IM

Assuming prelim IM alone guarantees future opportunities.

- You must actively pursue categorical/advanced positions.

Ignoring visa timelines.

- Track when your visa expires and what transitions are required.

Not asking for help early.

- PDs, faculty mentors, and GME offices can be powerful allies if they understand your situation.

Thinking you must “choose forever” now.

- Many physicians evolve:

- Academic → hybrid community/academic → private practice

- Private → later academic appointments (especially clinically focused roles)

- Many physicians evolve:

Your first few years are about building core training, reputation, and immigration stability. The fine-tuning of academic vs private practice can happen later.

FAQs: Academic vs Private Practice for Non‑US Citizen IMGs in Preliminary Medicine

1. Can I go directly into private practice after a preliminary medicine year?

No. A preliminary medicine year alone does not qualify you for independent internal medicine practice in the US. You must:

- Complete a categorical residency in internal medicine (usually 3 years total), or

- Complete another full residency or advanced specialty that leads to board eligibility.

After that, you can pursue private practice or hospital-employed roles, depending on your visa and specialty.

2. Is academic medicine harder to enter as a foreign national medical graduate?

It can be more competitive, especially at top-tier research institutions, because:

- They may prefer strong research portfolios and US training.

- Some departments may be cautious about visa sponsorship.

However, many academic centers are very IMG-friendly, especially in internal medicine and its subspecialties. If you:

- Perform well clinically

- Build some academic output (QI, case reports, small studies)

- Secure strong letters and mentors

you can absolutely enter and thrive in academic medicine as a non-US citizen IMG.

3. Which path is better for my visa situation: academic or private practice?

There is no universal answer; it depends on your visa type and geography.

- On J‑1:

- Many J‑1 waiver jobs are in community or hospitalist roles (which may feel more like private practice or community academic), but some academic centers in underserved areas also offer waiver positions.

- On H‑1B:

- Large academic centers and hospital systems are often more comfortable sponsoring H‑1B and green cards.

- Smaller private practices may be less experienced but can still be an option if they have good immigration counsel.

Practical strategy:

Focus on training at institutions with proven visa support, then decide on academic vs private once you have board eligibility.

4. I’m still unsure between academic and private practice. What should I do during my prelim year?

Keep your options open:

- Excel clinically and build a strong reputation.

- Participate in at least one academic project (QI, case report, small study).

- Get involved in some teaching, even if informal.

- Talk to:

- Academic hospitalists and subspecialists

- Community hospitalists and private practitioners linked to your hospital

Use your prelim year as a career observation and networking period. What you like and dislike about various attendings’ careers will guide your own choice later.

As a non-US citizen IMG in Preliminary Medicine, you are navigating one of the most complex intersections of training, immigration, and career decision-making. You do not need to perfectly define your future academic vs private practice identity today. What you do need is to be deliberate: maximize your prelim year, understand your visa landscape, cultivate mentors, and keep both doors open until your experience and opportunities clearly point the way forward.