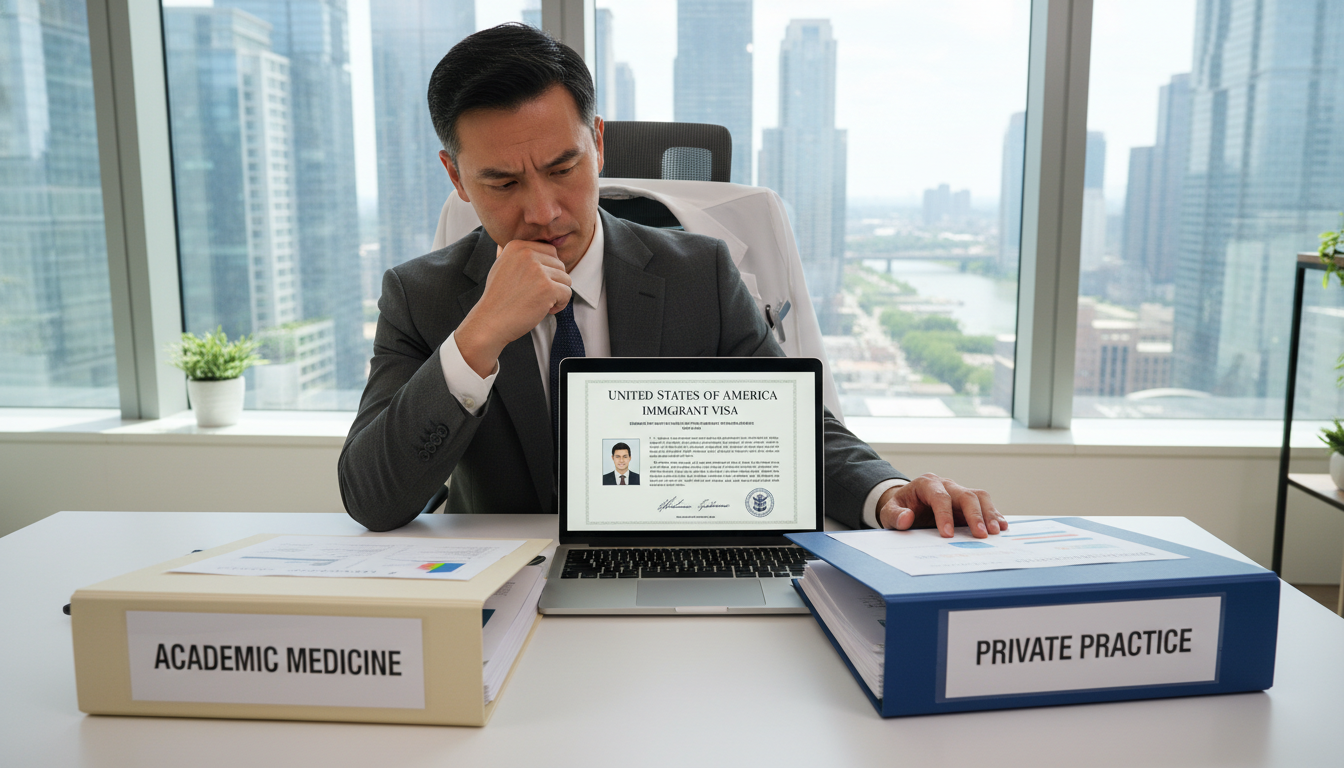

Choosing between an academic medicine career and private practice is one of the most consequential decisions you will make as a non-US citizen IMG pursuing cardiothoracic surgery in the United States. Beyond lifestyle and income, your decision affects your visa strategy, fellowship opportunities, research trajectory, and long‑term prospects in heart surgery training and practice.

This article breaks down the realities—financial, professional, and immigration‑related—of academic vs private practice cardiothoracic surgery for a foreign national medical graduate. The goal is to help you approach “choosing career path medicine” with clarity, not guesswork.

Understanding the Landscape: Where Cardiothoracic Surgeons Actually Work

Before comparing models, it helps to understand how cardiothoracic surgery is structured in the US and where non-US citizen IMGs most commonly end up.

Broadly, cardiothoracic surgeons practice in three overlapping environments:

Academic Medical Centers (AMCs)

- University-affiliated hospitals

- Robust cardiothoracic surgery residency and fellowship programs

- Heavy emphasis on research, teaching, and complex cases

Private Practice (Traditional or Employed)

- Independent group practices or surgeon-owned groups

- Or employed by private/community hospitals or large health systems

- Focus on high-volume clinical care and procedural work

Hybrid Models

- University-affiliated private groups

- Academic titles with primarily clinical duties

- Community-based programs with some teaching but limited research

As a non-US citizen IMG, you’ll encounter all three; however, visa issues, CV profile, and long-term goals may make certain options more realistic early in your career.

Reality check: For many foreign national medical graduates, the path into the US system almost always begins in academic environments (residency, fellowship), while long‑term practice may end up in a hybrid or private practice setting.

Academic Medicine in Cardiothoracic Surgery: Pros, Cons, and Visa Realities

Academic cardiothoracic surgery is usually based in large university hospitals or major tertiary centers. These are often where cardiothoracic surgery residency and advanced heart surgery training programs are located.

Core Features of Academic Cardiothoracic Surgery

Tripartite mission:

- Clinical care (often complex, high-risk cases)

- Teaching residents, fellows, and students

- Research (basic, translational, clinical, or outcomes)

Case mix

- More complex/referred cases: redo sternotomies, transplant, mechanical circulatory support (LVAD/ECMO), congenital anomalies (in congenital programs), high-risk oncology thoracic surgery.

- Greater exposure to cutting-edge technologies and trials.

Organizational structure

- You’re typically employed by a university, academic health system, or faculty practice plan.

- Rank progression: Assistant Professor → Associate Professor → Full Professor (with different tracks: clinical, research, clinician-educator, etc.).

Advantages of an Academic Medicine Career for Non-US Citizen IMGs

1. Stronger Visa and Sponsorship Infrastructure

Academic institutions are typically the most experienced and reliable in handling J‑1 waivers, H‑1B petitions, and green card sponsorship.

- More likely to sponsor H‑1B for residency, fellowship, and first faculty positions.

- Many already have legal departments or contracted immigration attorneys.

- Better understanding of requirements for a foreign national medical graduate, especially with complex timelines (e.g., moving from J‑1 fellowship to waiver job to permanent residency).

Practical tip: During interviews, explicitly ask:

- “Do you currently employ non-US citizen IMGs on H‑1B or O‑1?”

- “How many of your cardiothoracic faculty are on visas or have recently transitioned off visas?”

Programs used to working with IMGs will answer easily and concretely.

2. Enhanced Research and Academic Profile

If you envision a long-term academic medicine career with:

- NIH grants or major research funding

- Leading clinical trials in heart surgery training and innovation

- Developing new procedures or devices

- Becoming a recognized expert in a niche (e.g., aortic surgery, structural heart, lung transplant)

then academic practice is the most natural platform.

As a non-US citizen IMG, robust academic output is particularly useful for:

- Competing for top fellowships

- Building an O‑1 “extraordinary ability” visa or EB‑1/NIW green card case

- Being seen as a “value-add” in competitive markets

3. Teaching and Mentorship Opportunities

Many IMGs find deep satisfaction in teaching residents and fellows, especially after receiving mentorship from senior surgeons who helped them navigate the system.

Academic roles let you:

- Shape cardiothoracic surgery residency education

- Lead simulation programs or skills labs

- Serve as a visible role model for future non-US citizen IMGs

If you care about “giving back” and system-building, academic environments are inherently better suited.

4. Exposure to Subspecialization and National Leadership

Academic centers tend to support subspecialty development:

- Adult cardiac vs general thoracic vs congenital

- Structural heart, transplant, ECMO, oncologic thoracic

- Outcomes research, quality improvement leadership

They also often facilitate:

- Committee service in major societies (STS, AATS, EACTS)

- Speaking invitations and guideline-writing roles

This exposure can accelerate your profile both in the US and internationally.

Downsides and Trade-Offs of Academic Practice

1. Lower Starting Compensation (On Average)

Compared with many private practice jobs, academic salaries are often lower, especially early on. This can be significant if you have:

- Educational debt (US loans or loans from home country)

- Family to support or dependents abroad

- Expensive urban cost-of-living (e.g., Boston, NYC, SF)

You may have RVU incentives and bonuses, but pure income-maximization is rarely the strongest argument for academics.

2. Heavy Non-Clinical Responsibilities

- Grant writing

- IRB submissions, protocol development

- Lectures, curriculum design, committee work

- Formal evaluation and mentoring

These are intellectually rewarding but time-consuming. You must enjoy or at least tolerate academic “overhead” to thrive.

3. Metrics Beyond RVUs

In many academic roles, your value is measured by publications, teaching evaluations, grants, presentations, and service contributions. If you prefer a simple “work more, earn more” setup, this may feel misaligned.

Private Practice Cardiothoracic Surgery: Structure, Lifestyle, and Income

“Private practice” in US cardiothoracic surgery is more diverse than many applicants realize. It ranges from:

- Small, surgeon-owned groups in community hospitals

- Large multi-specialty practices employing CT surgeons

- Hospital-employed positions that function like private practice in many ways (especially financially and clinically)

Key Features of Private Practice CT Surgery

- Clinical volume and efficiency are prioritized; income usually tied closely to:

- Case numbers

- RVUs

- Call coverage

- Less formal teaching and research unless affiliated with a residency program

- More autonomy with scheduling, staff, and sometimes business decisions

Advantages of Private Practice for Non-US Citizen IMGs

1. Higher Income Potential

Over a career, many private practice surgeons earn substantially more than their academic counterparts. Private practice is particularly attractive if:

- You aim to maximize income after long years of training

- You have significant financial obligations

- You prefer a model where clinical productivity is the primary driver

You may also have:

- Partnership tracks with profit-sharing

- Opportunities for ownership in cardiac cath labs, imaging centers, or surgery centers (depending on legal/regulatory environment)

2. Operational Efficiency and Clinical Focus

If what you enjoy most is operating and patient care:

- Fewer academic meetings

- Less pressure to publish or obtain grants

- Simpler evaluation metrics (RVUs, patient satisfaction, quality metrics)

Many surgeons find private practice more straightforward: “take good care of patients, work hard, be available, and you’ll do well.”

3. Potentially More Geographic Flexibility

Private practice jobs may exist in:

- Smaller cities and rural areas

- Growing suburban regions with aging populations

- Places with less saturated cardiothoracic markets

For some non-US citizen IMGs, these locations are ideal for:

- J‑1 waiver positions (often in medically underserved areas)

- Less competition for cases

- Faster path to being a “senior” surgeon in the community

Challenges of Private Practice for Non-US Citizen IMGs

1. Visa Sponsorship is Less Predictable

This is the single biggest caveat for a foreign national medical graduate considering private practice:

- Smaller groups may have no prior experience with H‑1B, O‑1, or green card processes.

- They may be hesitant to invest money and time in immigration, especially with uncertain timelines.

- J‑1 waiver positions exist but require:

- Eligible location (often underserved or rural)

- Compliance with specific service commitments (typically 3 years)

Not all private practices can or want to navigate these issues.

Practical strategy: If you’re on J‑1:

- Target hospital-employed or large system jobs with an established pattern of J‑1 waivers.

- Confirm in writing (offer letter) that they will sponsor waiver and future status adjustments.

2. Business and Market Pressures

Private practice adds layers of:

- Negotiating contracts with hospitals and payers

- Dealing with changes in reimbursement and referral patterns

- Managing reputational risk in smaller communities

You may need basic comfort with:

- Business concepts (overhead, collections, payer mix)

- Networking with cardiologists, PCPs, and hospital administrators

Some IMGs, especially those without strong local networks, may initially find this environment harder to penetrate.

3. Fewer Built-In Academic Credentials

If you foresee ever wanting to:

- Move back into academia

- Apply for O‑1 or EB‑1 based on “extraordinary ability”

- Become a global thought leader

having limited publications, teaching, and formal academic appointments from a pure private practice role may slow that trajectory—though it doesn’t make it impossible, especially if you remain active in national societies and clinical research collaborations.

Choosing Between Academic and Private Practice: A Framework for Non-US Citizen IMGs

Rather than thinking “academic vs private” as a one-time, binary decision, approach it as a phased career strategy that aligns with:

- Immigration status and constraints

- Professional goals in heart surgery training and beyond

- Family needs and personal values

- Financial and lifestyle priorities

Phase 1: Training and Early Career (Residency + Fellowship + First Job)

As a non-US citizen IMG in cardiothoracic surgery, your early path is heavily influenced by:

- Matching into a strong general surgery residency

- Securing a cardiothoracic surgery residency or integrated program

- Obtaining any additional subspecialty fellowship (e.g., advanced heart failure, structural heart, congenital)

During this phase, academic environments usually dominate because:

- Most training programs are at academic centers.

- Visa sponsorship is more reliable.

- You need cases, mentorship, and credibility more than pure income.

Key decisions early on:

- Are you building a strong academic portfolio (publications, presentations, QI projects)?

- Are you interested in a research year or postdoc (can be very beneficial for O‑1/EB‑1 prospects)?

- How will your visa type (J‑1 vs H‑1B) affect your first job choices?

Phase 2: First 3–7 Years of Practice

This is the stage where many foreign national medical graduates truly decide between an academic medicine career and private practice.

Questions to Ask Yourself

What visa or status am I on now?

- J‑1 waiver job? You are likely in a non-academic or hybrid setting for 3 years.

- H‑1B with academic employer? You may have more flexibility but must plan green card timing carefully.

Which activities energize me?

- Writing papers, leading research, mentoring? → Academic or hybrid.

- High-volume operating, building a community reputation, income-focused? → Private practice or hospital-employed roles.

How important is location and lifestyle?

- Will your family thrive in a small rural town (often J‑1 waiver environment)?

- Or do you strongly prefer major cities with robust schools, communities, and cultural familiarity?

What are my medium-term financial goals?

- Aggressive debt paydown and wealth-building?

- Or willing to trade some income for prestige, research, and teaching?

A Common Hybrid Strategy

Many non-US citizen IMGs follow a hybrid, staged path:

J‑1 waiver or first job in a community/hospital-employed or hybrid setting

- Build case volume and reputation

- Pay off debt and secure green card

Transition to a more academic or desired private practice environment once:

- Immigration is stable (green card or citizenship in progress)

- You have robust experience and bargaining power

- You can afford to “optimize for fit,” not just visas and first available offer

This approach acknowledges that immigration constraints are often the dominant factor early on, but should not lock you permanently into a non-ideal career model.

Practical Career Planning Advice: Contracts, Negotiations, and Long-Term Flexibility

Evaluating an Academic Offer

When considering an academic faculty position, especially your first:

Look for:

- Clear breakdown of expectations:

- Clinical FTE vs research vs teaching

- Call responsibilities and case distribution

- Protected time for research (if promised) and how it’s actually enforced

- Mentorship:

- Is there a senior faculty member committed to your development?

- Will they support your leadership roles in societies and conferences?

Ask explicitly about:

- Visa sponsorship: H‑1B vs O‑1 vs green card timing

- Start-up support for research (funds, coordinators, lab space)

- Promotion criteria: What do they expect by year 3 and year 5?

Evaluating a Private Practice or Hospital-Employed Offer

For private practice, especially as a non-US citizen IMG:

Look for:

- Type of compensation: salary, RVU-based, or hybrid

- Partnership track: timeline, buy-in, and transparency of financials

- Case volume and referral base (talk to cardiologists in the system if possible)

- Call load and backup coverage

Visa/immigration red flags:

- “We’ve never sponsored anyone before, but our lawyer says it should be fine”

- Vague promises about J‑1 waiver or green card without written commitments

- Reluctance to connect you with the hospital’s immigration office or prior IMG hires

Non-negotiable for J‑1 IMGs:

Confirm that the position qualifies for a J‑1 waiver (Conrad 30, VA, ARC, HHS, etc.) before you commit.

Maintaining Long-Term Flexibility

Regardless of path, protect your future options:

Maintain some academic footprint, even in private practice:

- Participate in quality improvement projects

- Present at regional or national meetings

- Co-author clinical or outcomes papers

- Obtain adjunct academic appointments if possible

Network actively in STS, AATS, and other societies:

- Attend annual meetings

- Join committees or interest groups

- Present cases or posters, even if from community practice

This ensures that if you wish to switch from private practice to academia—or the reverse—your CV tells a coherent story of ongoing engagement and growth.

FAQs: Academic vs Private Practice for Non-US Citizen IMG in Cardiothoracic Surgery

1. Is it harder for a non-US citizen IMG to get a job in academic or private practice cardiothoracic surgery?

It depends more on visa status, networking, and timing than strictly on academic vs private. That said:

First job: Academic and large hospital-employed roles are often more accessible because they:

- Have established experience with IMGs and visas

- Value your academic track record from residency/fellowship

Later career: Once you have a green card or citizenship and solid experience, private practice options broaden significantly.

2. If I start in private practice, can I move into academic medicine later?

Yes, but it’s easier if you maintain academic engagement:

- Keep some publications or QI work going

- Remain active in professional societies

- Seek adjunct faculty appointments or teaching roles at nearby residency programs

An academic move is most plausible if your private practice experience includes:

- High case volume

- Specialized skills (e.g., TAVR, aortic surgery, transplant/ECMO, advanced thoracic oncology)

- Evidence of clinical excellence and leadership

3. Which path is better for obtaining a green card: academic or private practice?

Both can work, but the implementation differs:

Academic centers:

- Often use EB‑2 PERM, EB‑1B (outstanding professor/researcher), or even support EB‑1 or NIW strategies for highly productive surgeons.

- Have structured processes and immigration offices.

Private practice / hospital-employed:

- Commonly use EB‑2 PERM pathways, but processes can be slower or less familiar.

- Requires careful coordination with the employer and sometimes external attorneys.

For many non-US citizen IMGs, initial academic employment simplifies the early immigration steps, especially if you’re targeting EB‑1/O‑1.

4. What if my main goal is to become a high-volume, technically excellent surgeon and I don’t care much about research?

In that case, either:

- Clinical-track academic roles (with minimal research expectations), or

- Hospital-employed or private practice jobs in busy centers

could fit well.

Your decision may then hinge on:

- Visa practicality (which employer can actually sponsor and support you)

- Location and lifestyle

- Income expectations

Even if you’re not research-focused, consider small academic activities—teaching, quality projects, or case reports—for flexibility and immigration benefits.

For a non-US citizen IMG in cardiothoracic surgery, the choice between academic medicine and private practice is less about “picking the right team” on day one and more about strategically sequencing your training, first job, and long-term moves.

Anchor your decisions in three pillars: immigration realities, professional fulfillment, and personal/family priorities. If you regularly reassess these over time, you can build a career that is both sustainable and deeply rewarding—whether in an academic heart center, a thriving private practice, or a hybrid of both.