Understanding the Landscape: Why This Choice Matters for IMGs in ENT

For an international medical graduate (IMG) entering or completing an ENT residency, choosing between academic medicine and private practice will shape almost every aspect of your professional life. It influences not only your day‑to‑day schedule, but also your visa strategy, income trajectory, research opportunities, geographic flexibility, and long‑term satisfaction.

Otolaryngology is a relatively small, competitive specialty. The otolaryngology match is challenging for IMGs, and those who succeed often have strong research backgrounds, advanced degrees, or prior clinical experience abroad. That same background can make an academic medicine career very appealing—but private practice may offer faster financial stability and broader autonomy. This IMG residency guide focuses specifically on weighing academic vs private practice in ENT for international graduates, especially in the post‑residency and job market phase.

In this article, you’ll learn:

- How academic and private ENT practices differ in structure, culture, and expectations

- Unique considerations for IMGs (including visas, sponsorship, and promotion)

- Financial and lifestyle implications, with realistic examples

- How to choose a career path in medicine that matches your goals and personality

- Practical steps to keep both options open during residency and fellowship

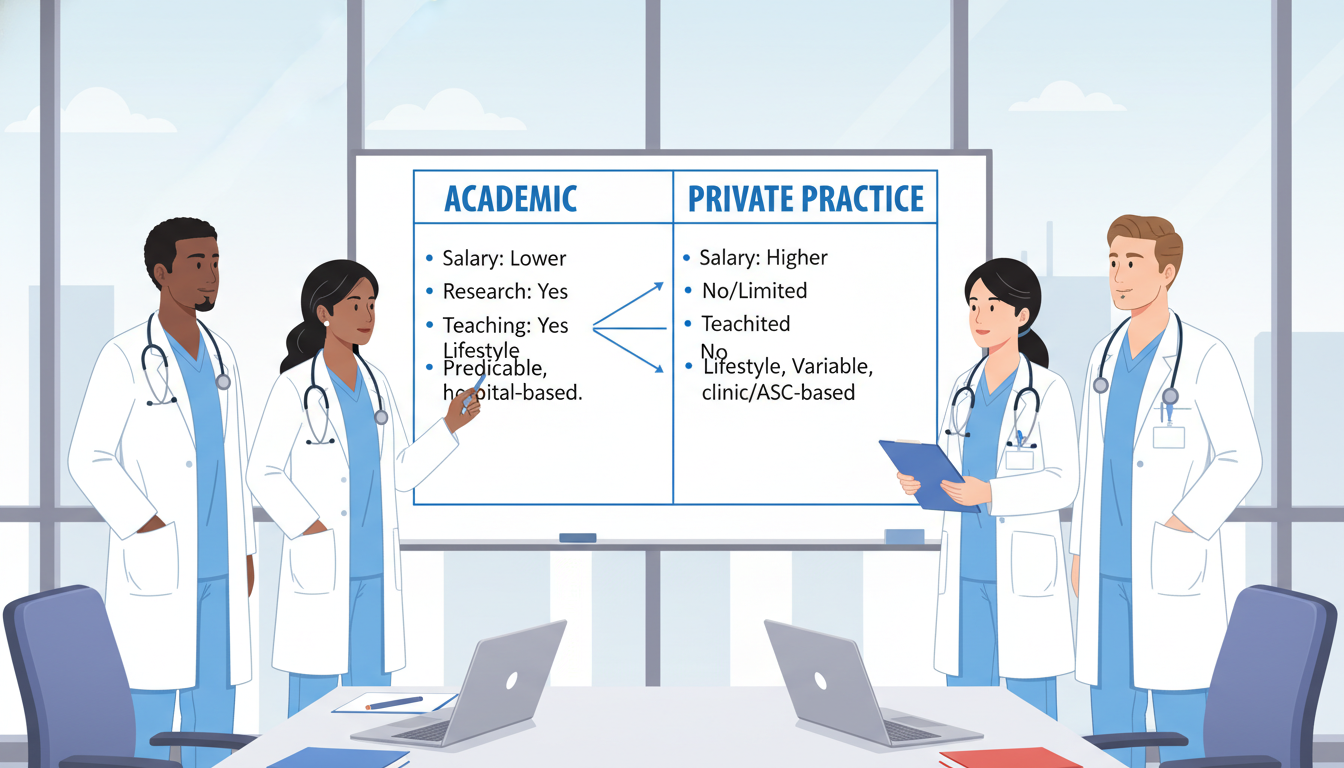

Defining Academic vs Private Practice in Otolaryngology

Before comparing, it’s critical to define what “academic medicine” and “private practice” actually mean in ENT—because in today’s environment, the lines are often blurred.

What Is “Academic” Otolaryngology?

Academic otolaryngology typically refers to positions at:

- University hospitals or medical schools

- Large teaching hospitals with residency or fellowship programs

- Research‑intensive centers (e.g., cancer institutes, children’s hospitals affiliated with universities)

Common features:

- Tripartite mission: Clinical care, teaching, and research

- Faculty titles: Assistant/Associate/Full Professor or Clinical Instructor

- Teaching: Supervising residents and medical students in clinic, OR, and classroom

- Research: Variable expectations—from minimal QI projects to substantial grant‑funded laboratories

- Compensation: Salary‑based, often with incentive components tied to productivity and/or academic achievements

- Infrastructure: Access to multidisciplinary tumor boards, advanced equipment, and subspecialized colleagues

For many IMGs, an academic medicine career feels like a natural extension of their path into the otolaryngology match—especially if their residency “ticket” depended on research or faculty connections.

What Is “Private Practice” in ENT?

Private practice ENT encompasses a wide spectrum of settings:

- Traditional small groups: 2–10 ENT surgeons in community or suburban settings

- Large ENT groups: Multisite practices, sometimes multi‑state, with audiology, allergy, and facial plastics services

- Hospital‑employed models: Technically “private” in the sense of not being a university faculty role, but salary‑based under a hospital or health system

- Solo practice (less common for new grads): One surgeon owning or buying into a clinic

Common features:

- Primary focus: Clinical care and productivity

- Compensation: Largely volume‑ and RVU‑based (work you do = money you earn)

- Teaching/research: Limited; may occur informally or through visiting students but not usually a core duty

- Business component: Varies; from heavy involvement in practice management to mostly clinical work with admin support

- Greater autonomy: Scheduling, case mix, and practice style can be more individualized

Many private practices also collaborate with academic centers, participate in clinical trials, or host rotating students, so “non‑academic” does not always mean “no teaching or research.”

Hybrid Models: The Gray Zone

You may also find hybrid positions that blur traditional boundaries:

- Private practice with academic appointment: You work in a community practice but hold a volunteer or part‑time faculty title, teaching residents a few days per month.

- Academic–affiliated community hospitals: You’re employed by a hospital that hosts residents from a nearby university but is not the main campus.

- Hospital‑employed ENT with minimal research: Technically part of an “academic enterprise” but functionally a high‑volume clinician.

As an international medical graduate, it’s crucial to look beyond the label and carefully examine actual duties, visa sponsorship, promotion tracks, and expectations.

Key Differences: Academic vs Private Practice Through the IMG Lens

1. Clinical Work and Case Mix

Academic ENT

- More complex and tertiary referrals: advanced sinus disease, skull base tumors, complex head and neck cancers, revision surgeries, pediatric airway cases.

- Subspecialization is common: rhinology, otology/neurotology, laryngology, facial plastics, pediatric ENT, head & neck oncologic surgery.

- More time spent supervising learners: teaching in OR may slow cases but can be fulfilling.

Private Practice ENT

- Case mix depends on setting:

- Community practice: ear infections, sinusitis, obstructive sleep apnea, thyroid disease, routine head & neck surgeries, office procedures.

- Large ENT group in urban area: still robust, with some advanced cases but fewer extremely rare conditions.

- More emphasis on efficiency and volume: shorter clinic visits, more procedures in office (e.g., turbinate reduction, balloon sinuplasty).

IMG Consideration:

If your long‑term dream is to become a highly subspecialized academic surgeon, a university‑based case mix often better supports that pathway. If you enjoy a broad range of bread‑and‑butter ENT and want earlier autonomy, private practice might be appealing.

2. Research and Teaching Expectations

Academic Medicine Career

- Research is often part of your job description:

- May range from small retrospective studies to large multi‑center trials or basic science.

- Some institutions expect grant funding (e.g., NIH) for promotion.

- Time is allocated for scholarly work—but in reality, this time may be squeezed by clinical demands.

- Teaching responsibilities:

- Didactic lectures for residents and medical students.

- Supervision in clinic and OR.

- Participation in curriculum development, exams, and mentorship.

Private Practice vs Academic

- Private practice usually has minimal formal research expectations. However:

- Some large groups voluntarily participate in clinical registries or trials.

- You can publish case reports, participate in multi‑center studies, or collaborate with academics.

- Formal teaching is less frequent, although:

- You may host rotators, give occasional lectures, or serve as adjunct faculty.

IMG Consideration:

If your visa pathway, residency match success, or personal interests were built around research, abandoning research entirely might feel like a loss. But be realistic about how much you truly enjoy research vs. how much you did it for the otolaryngology match and residency application. Your honest answer should heavily inform your choice.

3. Compensation and Financial Trajectory

Discussing income is essential for choosing a career path in medicine, particularly for IMGs who may carry international debt or family responsibilities abroad.

Academic ENT Compensation

- Generally lower starting salary than private practice in the same region.

- More stable, salary‑based with defined benefits (retirement, health, CME, sometimes loan assistance).

- May offer:

- Protected time for research/teaching (which indirectly lowers clinical income).

- Incentive bonuses based on RVUs, quality metrics, or academic output.

- Long‑term, some academics maintain moderate income while others (especially high‑volume subspecialists) can be quite competitive—though still often below top private practice earners.

Private Practice ENT Compensation

- Typically higher earning potential, especially after the first few years:

- Initial “guarantee” salary or draw while building a patient base.

- Transition to productivity‑based income or partnership track.

- Partnership in a successful ENT group can significantly increase income through:

- Profit‑sharing from ancillaries (audiology, allergy, imaging, surgery centers).

- Equity in real estate or equipment.

- Risk: income can fluctuate with local market, payer mix, or policy changes.

IMG Consideration (Example)

- Dr. A, an IMG completing an ENT residency, has $300,000 in combined debt and family support obligations.

- Academic offer: $310,000 base + modest bonus, strong research time, H‑1B sponsorship.

- Private practice offer: $400,000 guarantee for 2 years, then partnership track with potential >$600,000, but less experience with visas.

For many IMGs, financial pressure is significant. However, money should be weighed alongside visa stability, family needs, and career satisfaction. Short‑term higher salary may not compensate for long‑term misalignment with your interests.

4. Workload, Lifestyle, and Autonomy

Academic ENT Lifestyle

- Work hours: can be long, especially early on, balancing clinic, OR, research, teaching, and administration.

- Call: often more intensive due to complex cases and trauma at tertiary centers.

- Schedule: may be less flexible, influenced by residency program needs and institutional policies.

- Autonomy: constrained by academic structures; decisions may require committee approval, and changes move slowly.

Private Practice ENT Lifestyle

- Work hours: high initially while building a practice; later can be more controllable.

- Call: varies widely—community hospitals may have lighter call, but you might cover multiple facilities.

- Schedule: more flexible; you can eventually tailor your days, vacation, and even case mix.

- Autonomy: more direct control over:

- How you schedule patients

- Which procedures you offer

- Business decisions (if partner)

IMG Consideration:

As an international medical graduate, you may have fewer geographic options initially due to visa needs—but within those constraints, private practice can still offer significant control once settled. Academic roles may demand more committee work and teaching time, which might affect your ability to travel abroad or support family.

5. Visa, Sponsorship, and Immigration Strategy

For IMGs, immigration issues are often the deciding factor in academic vs private practice.

Academic Centers

- More familiar with visa sponsorship (H‑1B, O‑1) and sometimes even permanent residency sponsorship.

- University‑affiliated jobs may be cap‑exempt H‑1B, which allows more flexibility in timing and lottery issues.

- Some academic hospitals have established processes for:

- Transition from J‑1 waiver to H‑1B

- Green card sponsorship (EB‑1, EB‑2 NIW, etc.).

Private Practice

- Smaller practices may have limited experience with visas; some avoid IMG hires because of perceived complexity.

- Hospital‑employed private roles may offer more robust sponsorship than small independent groups.

- J‑1 waiver positions (e.g., underserved areas) are frequently in non‑academic community sites, not major academic centers.

- Many of these are functionally private practice or hospital‑employed.

IMG Strategy Tip

If you are on a J‑1 visa, you will almost certainly need a J‑1 waiver job, which is often:

- In a rural or underserved area

- Frequently not a major academic center

- Sometimes a hybrid or hospital‑employed community ENT position

For IMGs on H‑1B or O‑1, academic pathways may feel more straightforward due to institutional experience. When evaluating offers, directly ask:

- Does the employer currently sponsor H‑1B/O‑1 for surgeons?

- Do they support green card applications? On what timeline?

- Have they previously employed IMGs in ENT or other surgical specialties?

Immigration security may outweigh other factors, especially early in your career.

6. Promotion, Prestige, and Long‑Term Career Growth

Academic Promotion Path

- Formal ranks: Instructor → Assistant Professor → Associate Professor → Professor.

- Criteria vary but often consider:

- Publications, grants, presentations

- Teaching evaluations

- Clinical excellence and leadership roles

- Titles and promotion can be important if you aspire to:

- Department chair roles

- National society leadership

- International research collaborations

Private Practice Advancement

- Promotions are more business‑oriented:

- Associate → Partner → Senior Partner

- Leadership roles like medical director, managing partner, or group president.

- Prestige is driven by:

- Regional reputation, patient outcomes, referral network

- Contributions to professional societies and community.

IMG Perspective:

In some cultures, academic titles carry immense prestige and may be valued by family or future plans to return home. For others, financial stability and lifestyle carry more weight. Consider your long‑term goals, including whether you might eventually:

- Move back to your home country and take an academic post

- Apply for leadership positions in international ENT societies

- Transition into administration, industry, or policy (often easier from academic roles)

How to Decide: A Structured Approach for IMGs in ENT

Step 1: Clarify Your Core Priorities

Ask yourself, in order of importance:

- Immigration security – What visa do I have now, and what pathway do I need?

- Financial needs – Do I have major loans or family obligations? Do I need rapid income growth?

- Professional identity – Am I more excited by teaching and research, or by high‑efficiency clinical practice?

- Geographic factors – Where can I legally work? Where does my family want to live?

- Lifestyle preferences – Do I prefer structured environments or entrepreneurial ones? How do I feel about business management?

Write these priorities down. When comparing specific job offers, score each one against your personal priorities rather than abstract notions of “academic vs private practice.”

Step 2: Evaluate Real‑World Job Descriptions, Not Labels

An IMG residency guide often emphasizes that job titles can be misleading. For each opportunity:

- Ask about:

- Expected annual RVUs or case volume

- Protected time for research and teaching (if academic)

- Call frequency and scope

- Support staff and resources (APPs, scribes, research coordinators)

- Visa and green card processes

- Request to:

- Speak with current IMGs in the department or practice

- Observe a clinic or OR day if possible

- See a sample workweek schedule

You might find an “academic” job that is 95% clinical with minimal research—and a “private” job that offers collaborative projects with academic colleagues.

Step 3: Consider Your Time Horizon

Think in phases:

- Early phase (first 3–5 years):

- Immigration status stabilization

- Loan repayment and financial foundation

- Skill consolidation and subspecialty development

- Mid‑career (5–15 years):

- Leadership roles, academic promotion or partnership

- Family needs (schools, spouse career)

- Geographic stability

- Late career:

- Flexibility, partial retirement options

- Desire for legacy (education, research, community impact)

Your first job doesn’t have to be your forever job. Some IMGs:

- Start in a J‑1 waiver community/hospital‑employed role → Once stable and with green card, move into academic ENT.

- Start academic → Later transition to private practice or industry for lifestyle or financial reasons.

Step 4: Keep Both Doors Open During Residency/Fellowship

To maintain flexibility between academic and private paths:

- Build an academic portfolio:

- Engage in research (at least a few solid publications).

- Present at national ENT meetings.

- Develop teaching skills and request formal feedback.

- Develop clinical efficiency and autonomy:

- Learn practice‑building basics: scheduling, coding, RVUs, clinic management.

- Ask mentors about “real world” ENT outside academia.

- Network with both academic and private ENT surgeons:

- Attend local ENT society meetings.

- Seek shadowing experiences during elective time.

- Ask grads from your program about their job satisfaction.

This approach ensures that when you finally choose academic vs private practice, you’re pulled toward one path by authentic interest rather than pushed by a lack of options.

Practical Examples: Profiles of IMGs in ENT Career Paths

Example 1: Dr. S – Research‑Driven Academic Otolaryngologist

- Background: IMG with PhD in cancer biology, strong publication record.

- Residency: University ENT program; matched largely on research strength.

- Fellowships: Head & Neck Oncology and Microvascular Reconstruction.

- Career choice: Assistant Professor at NCI‑designated cancer center.

Why academic?

- Enjoys designing clinical trials and translational studies.

- Feels fulfilled mentoring residents, especially other IMGs.

- Comfortable with lower salary because spouse has stable income; institution offered cap‑exempt H‑1B and EB‑1 sponsorship.

Challenges:

- Balancing OR time with grant writing.

- Pressure to publish and obtain funding for promotion.

Example 2: Dr. R – Entrepreneurial Private Practice ENT

- Background: IMG with strong clinical performance but modest research.

- Visa: J‑1; required waiver job after residency.

- Job: Hospital‑employed ENT in underserved area, moving to large private group after waiver completion.

Why private?

- Financial goals: support extended family and repay loans quickly.

- Enjoys wide variety of general ENT and office procedures.

- Long‑term aim to become partner and expand services (allergy, audiology).

Challenges:

- Managing business aspects and negotiations.

- Initially limited exposure to complex tertiary cases.

Example 3: Dr. L – Hybrid Academic–Community Otolaryngologist

- Background: IMG with balanced interest in teaching and high‑volume clinical work.

- Job: Community hospital‑based ENT with volunteer faculty appointment at nearby university.

Why hybrid?

- Gets benefits of academic title and teaching residents 1–2 days/month.

- Still enjoys high productivity and income more typical of private practice.

- Hospital is experienced with visa sponsorship, offering stable immigration pathway.

This hybrid model can be especially attractive to IMGs looking for both academic identity and private practice advantages.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. As an IMG, is it harder to get an academic ENT job compared to private practice?

It depends more on your training pedigree, research output, and subspecialty than on your IMG status alone. Many academic ENT departments are enthusiastic about high‑performing IMGs, especially those with strong research backgrounds. However:

- Highly competitive academic positions (e.g., at top‑tier research institutions) often prioritize candidates with substantial scholarly portfolios.

- Some smaller academic centers focus more on clinical productivity and welcome IMGs willing to teach and do modest research.

- Private practices may hesitate if they lack visa experience but are otherwise open to IMGs with solid training and references.

Your best strategy is to cultivate excellence in residency, be transparent about your visa needs, and seek mentors who can advocate for you.

2. Can I move from private practice into academic ENT later?

Yes, but it can be more challenging if you have no recent research or teaching activity. To ease this transition:

- Maintain involvement with teaching (adjunct faculty roles, lectures to residents).

- Continue publishing case reports, reviews, or collaborative studies when possible.

- Stay active in professional ENT societies and present at meetings.

Academic departments hiring mid‑career surgeons often want evidence that you can contribute to education and scholarship, not just clinical volume.

3. How do I judge whether a private practice is IMG‑friendly?

Key signs of an IMG‑friendly private practice:

- Clear, documented experience sponsoring visas for physicians (preferably surgeons).

- Willingness to involve an experienced immigration attorney.

- Transparent partnership track and written explanation of buy‑in, compensation formulas, and expectations.

- Positive feedback from current or former IMG colleagues (ask to speak with them directly).

Be wary of vague answers about visas, unstructured partnership promises, or reluctance to put terms in writing.

4. If I enjoy teaching but not research, is academic ENT still a good choice?

Yes—many institutions have clinician‑educator tracks where promotion is based more on teaching and clinical excellence than grant funding. When interviewing:

- Ask specifically about different promotion tracks and expectations.

- Clarify how teaching contributions are measured and rewarded.

- Explore hybrid or community‑based roles with substantial teaching responsibilities but less research pressure.

Alternatively, a private practice position with a volunteer faculty appointment at a nearby residency program can offer extensive teaching opportunities without heavy research requirements.

Choosing between academic and private practice as an international medical graduate in otolaryngology is not a one‑time, irreversible decision. It is a dynamic process, closely tied to your immigration journey, financial reality, personal values, and evolving interests. By understanding the true differences—beyond labels—and deliberately aligning them with your own priorities, you can build a career in ENT that is not only successful on paper, but deeply satisfying in practice.