The myth that “a waitlist is basically a rejection” is statistically wrong.

For many U.S. medical schools, 20–60% of the eventual class comes from the waitlist. The data are uneven and school‑specific, but the pattern is clear: after May 15, admissions becomes a numbers game dominated by yield, movement, and timing.

This article dissects that game.

We will quantify realistic waitlist movement, focus on what happens after May 15 (the AAMC “Plan to Enroll” deadline), and translate aggregate data into approximate probabilities so you can assess your own chances with something better than wishful thinking.

1. The structural math of waitlists

At its core, waitlist movement is driven by three numbers for each school:

- Class size (C) – Target number of matriculants

- Total offers extended (O) – Acceptances sent out by the school

- Yield (Y) – Proportion of offers that turn into matriculants

The basic relationship is:

Y = C / O

Rearranged:

O = C / Y

The waitlist exists because schools do not know their actual yield in advance. They run an initial estimate of how many acceptances they can send out before May 15 without overshooting their class size, then use the waitlist to correct in real time as students commit elsewhere.

Typical numbers from AAMC data

From AAMC’s Table A-1 and historical admissions surveys:

- A common class size:

- Many MD schools: 120–170

- Larger publics: 180–260

- Typical offers per seat: 1.4–2.0

- Typical yield: 50–70% (private) vs 60–80%+ (in‑state publics)

So for a school with:

- Class size C = 150

- Yield Y = 0.60

Estimated offers needed:

- O ≈ 150 / 0.60 = 250

If the school sends 220 offers before May 15 and expects ~60–70% of those to stick, they will likely be short. The gap between who matriculates off the early offers and the class target is where waitlist movement comes from.

How many students are on a typical waitlist?

Schools rarely publish exact waitlist sizes, but reports from applicants, advisors, and the handful of public disclosures suggest:

- Small, selective private MD: 100–250 on the waitlist

- Large public MD: 200–600 on the waitlist

- Some DO schools: 200–800 total (with rolling movement)

So the raw percentages:

- If 40 people come off a 200‑person waitlist → 20% “gross” movement

- If 40 come off an 800‑person waitlist → 5% “gross” movement

But those numbers do not equal your probability, because:

- Many students hold multiple waitlists

- Some students decline immediately when called

- Higher‑ranked candidates are called first

- Some lists are tiered or partially pre‑ranked

Still, those percentages give a rough ceiling.

2. What actually happens after May 15?

May 15 (for AMCAS MD schools) is the first major inflection point.

By that date, applicants are expected to:

- Hold at most one MD acceptance in AMCAS (though they may still be on multiple waitlists)

- Select “Plan to Enroll” at their top MD school (not binding on its own)

Why this date matters: It forces attrition. Anyone holding 2–3 acceptances must release them, and all released seats become potential waitlist movement.

Timeline of waitlist movement

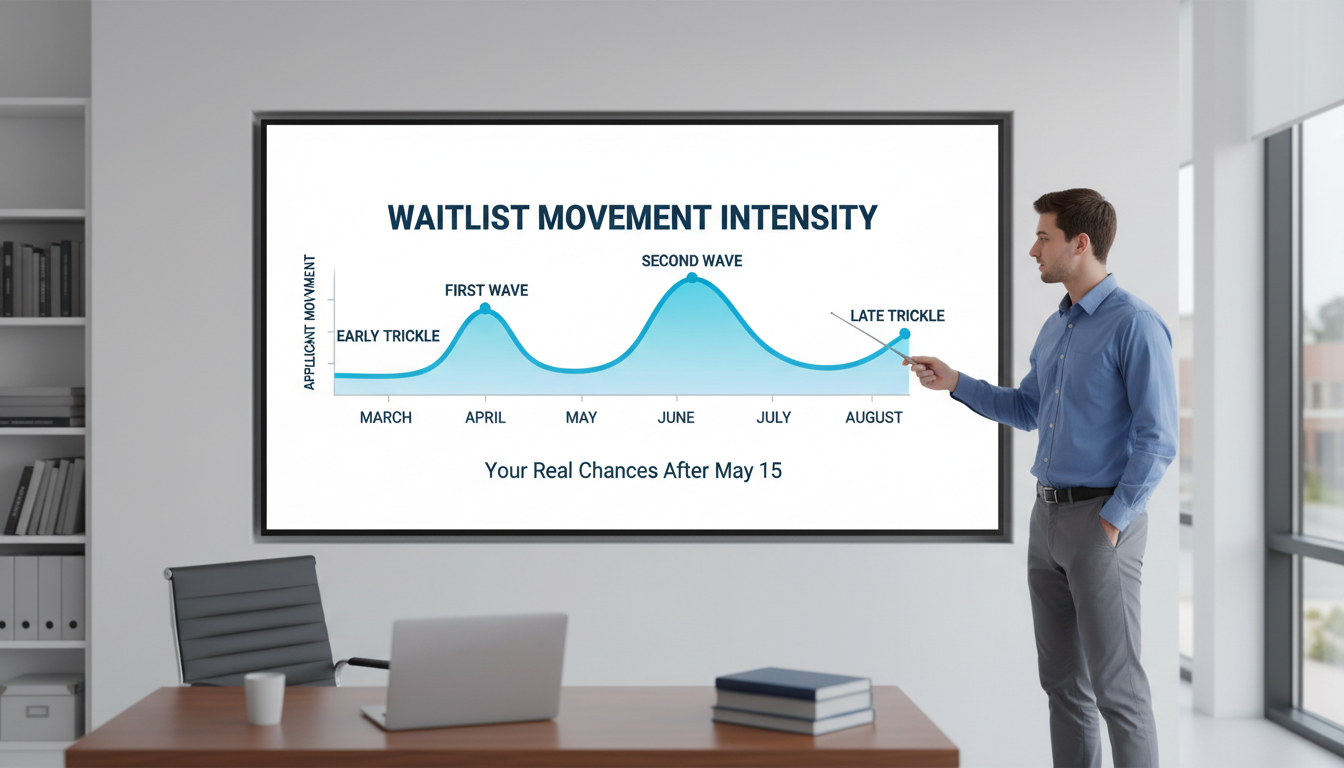

Using aggregated anecdotes, advisor surveys, and reported movement patterns, the curve for many MD schools looks like this:

Early trickle – March to early May

- A few top‑tier, high‑priority waitlisted applicants may get calls even before May 15, especially at schools protecting yield or filling specific mission fits.

- Volume is low. For many schools, under 10% of total waitlist movement happens before May 15.

First wave – May 15 to early June

- Applicants release extra acceptances → schools see real numbers.

- Admissions offices identify seat deficits and begin cycling through waitlist tiers.

- For many schools, 30–60% of waitlist movement occurs in this 3–4 week window.

Second wave – mid‑June to mid‑July

- Late financial aid decisions, last‑minute re‑applications, and off‑cycle withdrawals drive another wave.

- Another 30–40% of movement often lands here.

Late trickle – late July to start of orientation

- A few students withdraw for personal, financial, or visa reasons.

- Movement becomes sporadic: single‑digit numbers at most schools.

- DO schools and some MD programs with later start dates may still move a nontrivial number here.

By August, for the vast majority of MD schools, >90–95% of the class is locked.

3. Quantifying “your real chances” by school type

The question everyone cares about is not “how many move,” but:

“Given 1 waitlist offer at School X, what is the approximate probability that I matriculate there?”

There is no uniform answer, but we can outline realistic ranges by school type, using composite data and common patterns.

To keep the math grounded, assume:

- You are a typical waitlist candidate (not a clear superstar, not obviously weak)

- You have 1–2 acceptances elsewhere (so you are not desperate, but seriously interested)

- The school uses a ranked or tiered list, not fully random picks

Tier 1: Highly selective private MD (e.g., top 20 USNWR research)

Empirical patterns and occasional disclosures (and advisor networks) suggest:

- Total class size: ~150

- Initial offers: 250–300

- Final offers including waitlist: 300–350

- Approximate yield: 45–55%

- Waitlist size: 150–400

Observed waitlist movement:

- Often 10–40 students matriculate from the waitlist

- Rough estimate: 7–25% of the class from waitlist

If 25 students eventually matriculate off a 250‑person waitlist → raw 10% gross rate.

If 40 off a 400‑person waitlist → again 10%.

Your real odds:

- If you are at the top tier of that waitlist, your probability could be 30–60%

- If you are middle tier, maybe 5–20%

- If you are unranked / generic on a large list, closer to 1–10%

Data‑driven takeaway: At top programs, a waitlist is meaningful, but the base odds for a random person on that list are low, often in the single‑digit percentage range.

Tier 2: Mid‑ranked private MD and many out‑of‑state friendly publics

Pattern:

- Class size: 140–180

- Initial offers: 300–400

- Total offers: 350–500

- Yield: 35–50%

- Waitlist size: 200–600

These schools often compete heavily for applicants admitted to higher‑ranked programs. Their yield is more volatile, and they use the waitlist aggressively.

Observed waitlist contributions:

- Commonly 30–60 students matriculate from the waitlist

- For schools with heavy yield uncertainty, 20–40% of the class may be ex‑waitlist

Example scenario:

- Class size C = 160

- 55 eventual matriculants from waitlist (34% of class)

- Waitlist size WL = 350

Gross waitlist conversion: 55 / 350 ≈ 15.7%

But accounting for:

- Some waitlistees having better options and declining

- Some never answering calls in time or changing plans

The probability that any randomly selected individual on that waitlist ultimately matriculates is in the rough 8–18% band for many such schools.

If you are clearly in the top half of the waitlist (per advisor feedback or communication hints), your odds may be closer to 20–40%. If lower, 5–10% is more typical.

Tier 3: In‑state public MD with strong regional yield

Such schools (e.g., many state flagships) often show:

- Class size: 150–260

- Initial offers: 230–320

- Total offers: 250–350

- Yield: 65–85% in‑state component

- Waitlist size: 200–600

Their applicant pool is more “captive” in‑state, which stabilizes yield.

Observed waitlist movement:

- 10–30 matriculants from waitlist is typical

- In yield‑stable years, under 10% of class from waitlist

- In volatile years (policy or tuition shifts), movement may spike

Example:

- Class size C = 200

- 20 from waitlist → 10% of class

- Waitlist WL = 400

Gross probability: 20 / 400 = 5%

In other words, for many strong in‑state publics, the per‑person odds are often 2–8% if you are just “someone on the list.”

These schools also segment: in‑state vs out‑of‑state waitlists. It is not unusual for:

- In‑state WL: 5–15% eventual matriculation probability

- Out‑of‑state WL: 0–5% (and some years essentially zero movement OOS)

Tier 4: DO schools (AACOMAS)

DO schools have:

- Wider range of class sizes (150–350)

- Historically higher acceptance volume per seat (many apply broadly to both MD and DO)

- Often later decision timelines, with rolling movement into July and even August

Approximate pattern:

- Initial offers per seat: 2.0–3.0

- Yield: 30–55%

- Waitlist size: 200–800+

DO programs can pull substantial numbers off the waitlist as MD acceptances finalize.

Scenario:

- Class size C = 250

- 700 offers throughout cycle

- Yield ≈ 35.7%

- If ~100–140 students eventually come from the waitlist → 40–56% of class

With a waitlist WL = 600, gross probability: 100 / 600 ≈ 16.7%.

At many DO schools, the per‑person probability of matriculating from the waitlist might reasonably sit in the 10–25% range, with substantial variability by year.

4. Modeling your personal probability after May 15

To better approximate your own chances, you need to combine three factors:

- School‑level movement patterns

- Your likely position on the waitlist

- You vs the competition’s behavior

4.1 Step 1 – Estimate school‑level movement

Where you can:

- Check historical posts from current students or admissions offices

- Ask your premed advisor if they track how many students matriculate from specific schools’ waitlists

- Look for language from the school:

- “We typically admit a significant number of students from the waitlist” → usually >15–20% of class

- “Only a small number” → often <10% of class

Crude estimate method:

- High‑movement school: assume 30–70 matriculants from waitlist

- Medium‑movement: 15–40

- Low‑movement: 0–15

You can then compute:

Approximate gross rate = (estimated WL matriculants) / (approximate WL size)

Where WL size is a guess:

- Small private MD: 150–300

- Large public MD: 300–600

- DO: 400–800

4.2 Step 2 – Adjust for your likely ranking

Most schools do not tell you where you are on the list, but some signals matter:

- “High priority waitlist” / “upper tier waitlist” / “priority pool” → top half, sometimes top third

- Personalized outreach from Dean or admissions with specific encouragement → usually implies above median position

- Silence + generic template → could be anywhere

As a rule:

- Top third of a moderately sized waitlist: multiplier ~2–3x the gross rate

- Middle third: roughly similar to the gross rate

- Bottom third / unprioritized: 0.3–0.7x the gross rate

Example:

School appears to move ~30 people from a waitlist of 300 → gross = 10%.

- You are explicitly said to be in a “small upper group” → maybe 20–30% personal chance

- You get only generic messaging → likely close to that 10%

- You are on an “alternate” list that sounds secondary → maybe 3–7%

4.3 Step 3 – Account for your own behavior

Your probability of matriculating from a waitlist equals:

P(being offered) × P(you accept when offered)

The second term is often not 100%.

For example:

- If you already hold a strong MD acceptance with lower tuition, and the waitlist school is more expensive and only slightly higher ranked, your personal P(accept) might be 30–50%.

- If the waitlist school is your clear dream (geography, mission, or prestige), P(accept) might be 90–100%.

Some schools know or infer this from:

- Your “Plan to Enroll” choice reported to them after April 30 / May 15

- Your communication and letters of intent

- Pre‑interview statements

Schools are less likely to call waitlisted applicants who:

- Are clearly committed elsewhere (via “Commit to Enroll” at another institution)

- Have signaled lukewarm interest

So if you truly would attend if admitted, your effective probability of matriculating is close to P(being offered). If you are ambivalent, your actual chance of ending up there falls accordingly.

5. What the numbers say about post–May 15 strategy

With probabilities on the table, how should you behave after May 15?

Here is what the data and patterns support, rather than what “feels polite.”

5.1 Expected value of staying on a waitlist

From a decision‑analysis standpoint, consider:

EV = P(mat) × (value of that school to you – value of your current best option) – costs (deposit loss, logistics, stress)

Some realistic values:

- For a top‑tier MD waitlist where your chance might be 5–10% and the school is clearly above your current acceptance, the EV is often strongly positive. Dropping off that list prematurely is rarely rational unless you are certain you prefer your current option.

- For a low‑movement in‑state public MD where your estimated chance is 2–4% and your current acceptance is similar in quality and cost, the EV is marginal.

Since the “cost” of remaining on most waitlists is low (occasional emails, some mental bandwidth), the quantitative case usually favors staying on any list where you would realistically attend if accepted.

5.2 Timing of updates and letters

Empirical questions: do letters of interest or update letters actually change your odds?

Anecdotal and advisor‑collected data suggest:

- At schools that explicitly encourage post‑interview communication, meaningful, concise updates can move you from the middle band to the active consideration band. Think incremental boosts, not miracles.

- At schools that discourage extra communication, the marginal impact is negligible or even negative if overdone.

If we translate that into numbers:

- Suppose your “base” chance is 10%.

- A strong update at a place that welcomes them might nudge that to 12–15%.

- Multiple generic emails probably do not move the needle at all.

The data‑analyst view: treat letters of intent / interest as small multipliers on existing probability, not game‑changers that transform a 1% chance into 50%.

5.3 Managing cross‑school dependencies

There is strong interdependence: your acceptance at one school can drive someone else’s waitlist movement at another.

Example chain:

- You are waitlisted at School A and accepted at School B.

- On June 5, School A calls you.

- You accept.

- You then release School B.

- School B now calls someone on its waitlist on June 6.

This cascade means that movement is not fixed; it propagates as applicants shift. You cannot directly manipulate the network, but you can:

- Communicate honestly with schools about your intentions

- Release seats promptly when you know you will not attend

Ethically, that is the right behavior. Systemically, it slightly increases total waitlist movement across the ecosystem.

6. Concrete numerical scenarios

To anchor this in specifics, consider three simplified but realistic scenarios.

Scenario A – Mid‑ranked private MD, moderate WL

- Class size: 160

- Estimated total matriculants from WL: 45

- Estimated WL size: 300

- Your advisor says you are “in the upper half”

Gross rate: 45 / 300 = 15%

You are in upper half → multiplier ~1.5–2.0 → estimated personal P(offer) = 22–30%

You would strongly prefer this school to your current acceptance → P(accept if offered) ≈ 95%

Your P(matriculate) ≈ 0.22–0.30 × 0.95 → ≈ 21–29%

Interpretation: Your odds are materially real. You should behave as if this is a live option well into June.

Scenario B – Highly ranked research MD, deep WL

- Class size: 150

- Estimated WL matriculants: 20

- Estimated WL size: 350

- No signals about your rank; generic communications only

Gross rate: 20 / 350 ≈ 5.7%

Unknown position; assume you are typical → P(offer) ≈ 3–8%

You would absolutely attend if admitted → P(accept) ≈ 100%

P(matriculate) ≈ 3–8%

Interpretation: Emotionally difficult, statistically low. It is still rational to remain on the list, but you should make life and housing plans based on your current acceptance.

Scenario C – DO school, high movement

- Class size: 240

- Estimated WL matriculants: 90

- Estimated WL size: 600

- You are told you are on the “priority list”

Gross rate: 90 / 600 = 15%

Priority subset, maybe top 40% → multiplier 1.5–2.0 → P(offer) ≈ 22–30%

You prefer this DO school slightly to an MD school where you are accepted only if scholarship comes through; otherwise you might stay MD. Your P(accept if offered) is ~60–80%.

So P(matriculate) ≈ (0.22–0.30) × (0.60–0.80) ≈ 13–24%

Interpretation: Realistic possibility. You should track financial aid timing; your personal decision thresholds will matter as much as the school’s behavior.

7. The data‑driven bottom line

Stripped of anecdotes and emotions, the numbers around waitlist movement point to three core conclusions:

Waitlists are statistically meaningful, but not generous.

For many MD programs, 10–30% of the class arrives from the waitlist, but that often translates to single‑digit to low double‑digit probabilities for any given individual, especially at highly selective schools.Your true odds hinge on school type and your tier.

Mid‑tier private MD and many DO schools can offer 15–30%+ realistic chances for a well‑positioned waitlist candidate. Yield‑stable in‑state publics and top‑ranked privates often imply 2–10% for a generic waitlistee, unless you know you are near the top.Action matters at the margins, not the core.

You cannot turn a 3% chance into 80% with letters or clever strategy. You can, however, reasonably nudge your odds upward, align your behavior with your preferences, and make rational decisions based on approximate probabilities rather than pure hope.

If you hold a waitlist spot after May 15, you are not “basically rejected.” You are in a low‑to‑moderate probability queue in a system driven by yield math, cross‑school dependencies, and timing. Understanding that math lets you plan your summer, your finances, and your mindset with clarity rather than superstition.