As healthcare delivery, technology, and patient expectations rapidly evolve, the work of medical educators has never been more complex—or more important. Today’s educators must not only master vast clinical content, but also design effective Teaching Strategies, lead curriculum reform, foster Student Engagement, support learner wellbeing, and continuously invest in their own Professional Development.

This guide explores the top challenges faced by medical educators and offers practical, evidence-informed solutions you can apply in undergraduate, graduate, and continuing Medical Education and Healthcare Training settings.

1. Keeping Pace with Medical Advancements and Educational Innovation

The volume of medical knowledge is doubling at an ever-faster rate. Guidelines shift, new therapeutics emerge, and technologies such as AI and point-of-care ultrasound change what “core knowledge” looks like. At the same time, educational science is advancing, with new best practices for curriculum design and assessment.

Challenge: Information Overload and Curricular Obsolescence

Medical educators often feel pulled in multiple directions:

- New clinical evidence and guidelines outdate lectures within months.

- Emerging technologies (AI decision support, telehealth, genomics) demand curricular space.

- Accreditation bodies emphasize competencies—communication, systems-based practice, quality improvement—beyond traditional biomedical content.

Without a system, curricula can quickly become fragmented, inconsistent, or outdated.

Solutions: Strategic Professional Development and Curriculum Governance

1.1 Commit to Ongoing Professional Development

- Structured CME and CPD

- Schedule protected time for Continuing Medical Education (CME) and faculty development.

- Use targeted sources: specialty journals, guideline repositories (e.g., NICE, UpToDate, specialty societies), and Medical Education journals (Academic Medicine, Medical Teacher).

- Education-specific training

- Enroll in medical educator certificate programs or online faculty development courses (AAMC, AMEE, MedEdPORTAL resources).

- Engage in workshops on curriculum design, assessment, and feedback to pair pedagogical skills with clinical expertise.

1.2 Build Collaborative Knowledge Networks

- Local “scholarship in education” groups

- Form peer groups to review new guidelines, discuss evidence-based Teaching Strategies, and co-develop educational materials.

- Rotate responsibility for periodically summarizing key updates in your specialty and sharing them at faculty meetings.

- Use “educational champions”

- Identify faculty leads for specific domains (e.g., ultrasound, telemedicine, patient safety) who track developments and advise on integrating them into the curriculum.

1.3 Design Flexible, Competency-Based Curricula

- Competency-first approach

- Start with core competencies (clinical reasoning, communication, professionalism, systems-based care) and link content updates to those competencies.

- Use frameworks like ACGME milestones, CanMEDS, or national competency frameworks as anchors.

- Modular content design

- Create shorter, modular content (e.g., micro-lectures, case-based sessions) that can be updated quickly without overhauling entire courses.

- Curriculum mapping

- Map learning objectives to sessions and assessments. Curriculum management software can highlight redundancy and gaps and show where new content (e.g., AI in radiology) can fit.

2. Enhancing Student Engagement in a Changing Learning Culture

Today’s learners are digital natives with instant access to vast resources. Yet attention is fragmented, and many still default to passive note-taking and last-minute cramming, despite evidence favoring active learning for durable understanding and clinical reasoning.

Challenge: Moving Beyond the Passive Lecture

Medical educators are pressured to “cover” large volumes of content. Students may resist active learning, believing lectures are more efficient or “high-yield.” This tension can hinder deep learning and critical thinking.

Solutions: Active Learning, Tech-Enhanced Instruction, and Feedback Culture

2.1 Implement Evidence-Based Active Learning Strategies

- Case- and Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

- Use authentic clinical cases that mirror exam and real-world complexity.

- Have students generate differential diagnoses, identify data gaps, and propose management plans.

- Assign roles: team leader, scribe, “evidence officer” to look up and vet guidelines.

- Flipped Classroom Models

- Assign short pre-class content (10–15 minute videos, key readings, podcasts).

- Use in-class time for application: case discussions, role-plays, OSCE-style stations, or debates (e.g., “Treat vs. Watchful Waiting”).

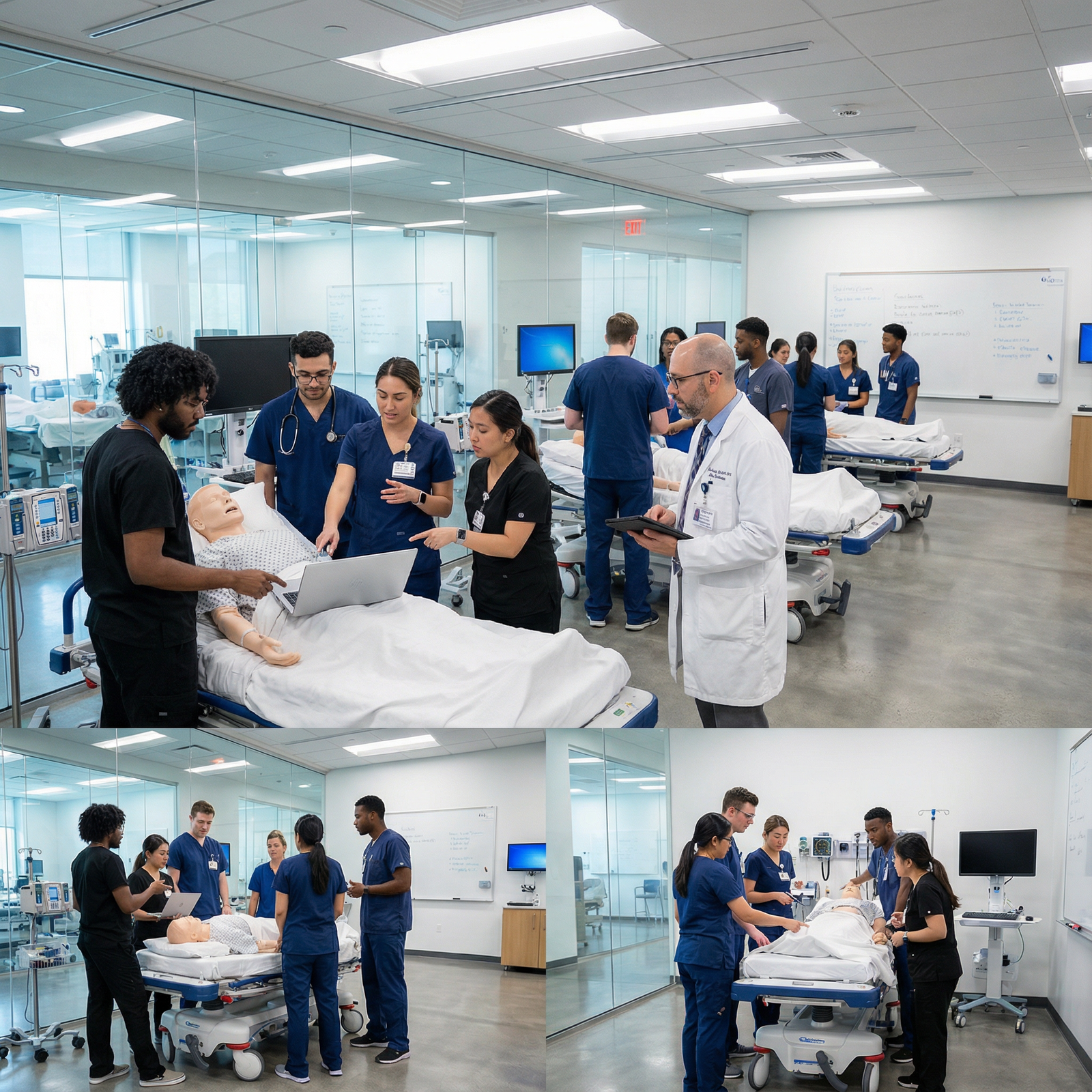

- Simulation-Based Education

- Integrate low- and high-fidelity simulations for resuscitation, communication with families, and interprofessional teamwork.

- Debrief systematically, focusing on clinical reasoning, communication, and human factors, not just technical skills.

2.2 Leverage Educational Technology Strategically

- Audience response systems

- Use tools (Poll Everywhere, Mentimeter, Kahoot) to check understanding in real time, normalize uncertainty, and keep attention high.

- Pose challenging questions that require explanation, not just recall.

- Learning management systems (LMS)

- Provide structured learning paths, curated resources, and discussion boards for asynchronous engagement.

- Use analytics (completion rates, quiz performance) to identify struggling learners early.

- Virtual and augmented reality

- Consider VR/AR for anatomy, procedural training, and rare clinical scenarios. This is particularly valuable when clinical case-mix is limited.

2.3 Build a Robust Feedback and Reflection Culture

- Frequent low-stakes feedback

- Use brief “one-minute preceptor” techniques in clinic:

- Get a commitment (“What do you think is going on?”)

- Probe for supporting evidence

- Teach a general principle

- Reinforce what was done well

- Correct errors with specific suggestions

- Use brief “one-minute preceptor” techniques in clinic:

- Peer and self-assessment

- Incorporate structured peer review in presentations, simulations, and small-group work.

- Use reflection prompts: “What is one thing you would do differently next time and why?”

- Transparent expectations

- Share explicit rubrics and example work products (e.g., exemplary H&Ps, progress notes) to clarify what excellence looks like.

3. Balancing Teaching, Clinical Work, Research, and Administration

Most medical educators are clinician-educators who juggle patient care, teaching responsibilities, research or QI, and administrative duties. Without intentional strategies, this workload can lead to chronic stress and burnout—for educators and learners alike.

Challenge: Role Overload and Burnout Risk

Competing demands can result in:

- Reduced time for high-quality teaching preparation.

- Delayed or superficial feedback to learners.

- Decreased scholarly productivity and stalled career progression.

- Emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and decreased job satisfaction.

Solutions: Time Management, Role Clarity, and Personal Sustainability

3.1 Practice Deliberate Time and Project Management

- Prioritize with purpose

- Use the Eisenhower Matrix (urgent vs. important) to identify tasks to do now, schedule, delegate, or drop.

- Protect blocks of time for high-value work (curriculum development, feedback on assessments).

- Batching and templates

- Batch similar tasks (emails, grading, meeting prep) rather than multitasking.

- Use templates for feedback, recommendation letters, and common emails to save time and maintain quality.

- Negotiate protected time

- During annual reviews or contract negotiations, explicitly discuss protected FTE for teaching and educational leadership roles.

- Link your contributions to accreditation standards, learner outcomes, and institutional priorities.

3.2 Delegate and Build Educational Teams

- Task-sharing

- Train junior faculty, fellows, or senior residents to co-teach, facilitate small groups, or manage logistics.

- Partner with administrative coordinators to handle scheduling, room bookings, and documentation.

- Mentorship and sponsorship

- Seek mentors for educational scholarship and career planning.

- Serve as a mentor yourself, gradually handing off responsibility to build capacity in your department.

3.3 Prioritize Personal Wellbeing and Role Modeling

- Self-care as a professional duty

- Schedule regular activities that replenish you: exercise, hobbies, family time.

- Use institutional wellness resources—counseling, peer support groups, faculty assistance programs.

- Set boundaries and model them

- Clarify expectations around email response times and after-hours availability.

- Demonstrate healthy behaviors in front of trainees: taking breaks, using vacation, and seeking help when needed.

4. Teaching Diverse Learners: Learning Styles, Backgrounds, and Needs

Medical classrooms and residency programs are increasingly diverse across culture, language, prior education, and lived experiences. While “learning styles” labels are oversimplified, learners do vary in how they best process and retain information, and in the supports they need to succeed.

Challenge: One-Size-Fits-All Teaching in a Diverse Environment

Diversity enriches learning but also creates challenges:

- Varied comfort with active learning and public participation.

- Differences in clinical exposure, language proficiency, and implicit norms.

- Neurodivergent learners, learners with disabilities, and those facing social or financial stressors.

Solutions: Inclusive Teaching, Universal Design, and Peer Learning

4.1 Use Multiple Modalities and Universal Design Principles

- Varied formats in every session

- Combine brief didactics with visuals, interactive questioning, small-group tasks, and practical demonstrations.

- Provide written summaries or key diagrams for visually and textually-oriented learners.

- Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

- Offer multiple means of representation (videos, text, diagrams), expression (written, oral, practical), and engagement (individual and group tasks).

- Provide materials in advance when possible to support learners who need more processing time.

4.2 Intentionally Foster Inclusive Learning Environments

- Set norms early

- Co-create ground rules around respect, participation, and constructive disagreement.

- Encourage “step up, step back”: frequent speakers give space; quieter learners are invited in.

- Culturally responsive teaching

- Acknowledge different communication styles and cultural perspectives on hierarchy, uncertainty, and help-seeking.

- Use diverse patient scenarios that reflect various backgrounds, languages, and social determinants of health.

4.3 Encourage Structured Peer-to-Peer Learning

- Near-peer teaching

- Use senior students or residents as small-group facilitators; they often explain complex topics in relatable ways.

- Near-peer OSCE coaching, skills labs, and review sessions can enhance Student Engagement and normalize struggle.

- Collaborative learning strategies

- Implement jigsaw activities, team-based learning (TBL), and peer instruction where learners teach components to each other.

- Emphasize shared responsibility for group success, not just individual performance.

5. Preventing and Addressing Burnout Among Students and Residents

Burnout, depression, and anxiety are major threats in Medical Education and Healthcare Training. They affect learning, professionalism, and patient care quality and can derail promising careers.

Challenge: High Stress, Hidden Suffering

Medical students and residents face:

- Long hours, sleep deprivation, and emotional exposure to suffering and death.

- High-stakes exams and “hidden curricula” around perfectionism and self-sacrifice.

- Stigma around mental health and fear that help-seeking will affect evaluation.

Solutions: Institutional Wellness, Supportive Culture, and Skills Training

5.1 Build Structured Wellness Programs

- Embedded mental health services

- Advocate for confidential, low-barrier counseling with clinicians not involved in assessment.

- Ensure residents and students can access care without punitive scheduling or stigma.

- Programmatic wellness activities

- Integrate regular wellness workshops on stress management, sleep hygiene, coping with medical errors, and building resilience.

- Use team-based debriefs after distressing cases to normalize emotional responses.

5.2 Create Supportive Mentorship and Coaching Systems

- Formal mentorship programs

- Pair learners with faculty mentors for career guidance and personal support.

- Encourage multiple mentors (clinical, research, wellbeing) to share the load.

- Coaching for performance and growth

- Distinguish coaching (developmental, non-evaluative) from formal evaluation.

- Use coaching to help learners set realistic goals, reflect on progress, and develop self-regulation skills.

5.3 Normalize Self-Care and Help-Seeking

- Curricular integration

- Explicitly teach self-care strategies: boundary setting, efficient studying, time management, and when to say no.

- Incorporate narratives from faculty or senior learners who sought help and recovered.

- Policy-level supports

- Promote duty hour adherence and safe coverage systems when learners are ill or overwhelmed.

- Review the learning environment for bullying, discrimination, or shaming and address problems promptly.

6. Designing Fair, Valid, and Competency-Aligned Assessments

Assessment drives learning. Yet designing assessments that are reliable, fair, and truly reflective of clinical competence is one of the most technically challenging aspects of Medical Education.

Challenge: Misalignment Between Teaching and Testing

Common problems include:

- Exams emphasizing recall rather than clinical reasoning or professionalism.

- Discrepancies between what is taught and what appears on exams.

- Inconsistent direct observation and subjective narrative evaluations in the clinical environment.

Solutions: Constructive Alignment, Multiple Measures, and Assessment Literacy

6.1 Align Outcomes, Teaching, and Assessment

- Constructive alignment

- Define clear learning outcomes (knowledge, skills, attitudes) first.

- Choose teaching methods and assessment formats deliberately to measure those outcomes.

- Use Bloom’s Taxonomy to ensure a range from recall to analysis, evaluation, and synthesis.

- Blueprinting assessments

- Develop test blueprints that map questions or stations to learning objectives and content domains.

- Periodically review item performance and adjust to avoid overemphasis on minutiae.

6.2 Use Multiple, Complementary Assessment Methods

- Written assessments

- MCQs and SAQs for knowledge and basic clinical reasoning.

- Script concordance tests (SCTs) for uncertainty and judgment.

- Performance-based assessments

- OSCEs and simulation-based assessments for communication, procedural skills, and emergency management.

- Workplace-based assessments (mini-CEX, Direct Observation of Procedural Skills [DOPS], multisource feedback) for real-world performance.

- Longitudinal assessment

- Portfolios that collect reflections, feedback reports, QI projects, and scholarly work over time.

- Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) to make holistic entrustment decisions about readiness for unsupervised practice.

6.3 Improve Faculty Assessment Skills

- Rater training

- Offer regular workshops on using rating scales, avoiding common biases (leniency, halo effect), and writing high-quality narrative feedback.

- Use shared video examples to calibrate across faculty.

- Feedback on assessments

- Provide learners with timely, specific feedback on exams and performance assessments, not just scores.

- Use exam item analysis to identify poorly performing questions and revise them.

7. Bridging the Gap Between Education and Real-World Clinical Practice

One of the most persistent critiques of Medical Education is that learners feel underprepared for the realities of independent practice—systems complexity, interprofessional teamwork, and real-time decision-making under uncertainty.

Challenge: Translating Theory Into Practice

- Classroom content may not match the “messiness” of real clinical environments.

- Learners struggle to integrate guidelines with individual patient values and system constraints.

- Fragmentation between pre-clinical and clinical phases creates silos.

Solutions: Integrative, Longitudinal, and Interprofessional Training

7.1 Early and Longitudinal Clinical Exposure

- Early clinical immersion

- Introduce clinical experiences in the first year: shadowing, patient interviews, OSCEs with standardized patients.

- Use longitudinal clerkships where learners follow patients over time rather than rotating in rigid blocks.

- Authentic clinical tasks

- Allow learners to participate meaningfully: call patients with results under supervision, write orders (cosigned), lead family meetings, or manage handoffs.

7.2 Interprofessional Education (IPE)

- Team-based learning with other professions

- Run joint sessions and simulations with nursing, pharmacy, PT/OT, social work, and other healthcare trainees.

- Focus on communication, role clarity, conflict resolution, and shared mental models.

- Systems and quality improvement projects

- Involve learners in QI and patient safety projects within real clinical units.

- Teach them to use tools like Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles, root cause analysis, and process mapping.

7.3 Continuous Curriculum-Clinical Feedback Loop

- Feedback from frontline clinicians

- Regularly solicit feedback from attending physicians, residents, and allied health staff on learner preparedness and gaps.

- Adjust curriculum to reflect current practice realities (e.g., telehealth workflows, EMR best practices).

- Developing “adaptive experts”

- Emphasize metacognition and life-long learning skills: framing clinical questions, searching literature, appraising evidence, and updating one’s practice.

8. Integrating Sustainability and Resource Stewardship into Medical Education

Healthcare is a major contributor to environmental impact, and resource constraints are a daily reality. Educators now have a responsibility to prepare learners to practice sustainably and steward limited resources wisely.

Challenge: Limited Time and Competing Priorities

Sustainability and planetary health feel essential—but also “one more thing” in an already packed curriculum. Educators may be unsure how to weave these themes into clinical training.

Solutions: Embedding Sustainability, Modeling Stewardship, and Using Digital Tools

8.1 Incorporate Sustainability into Existing Content

- Integrate, don’t just add

- Embed environmental impact and resource stewardship in existing topics: imaging appropriateness, antibiotic use, OR waste reduction, energy consumption.

- Use clinical cases that require balancing patient benefit, cost, and environmental impact.

- Teach high-value care

- Introduce frameworks for “Choosing Wisely” and high-value care alongside clinical reasoning.

- Discuss the carbon footprint and cost of unnecessary tests and treatments.

8.2 Practice Resource-Conscious Teaching

- Digital-first materials

- Prefer digital handouts, e-modules, and online portfolios over printed materials.

- Use virtual cases and simulations where physical resources are limited.

- Shared resources across programs

- Collaborate regionally or nationally to share curricula, assessment tools, and simulation scenarios, reducing duplication of effort.

8.3 Role Modeling Sustainable Professional Behavior

- Visible changes

- Reduce waste in skills labs and simulation centers where safe and feasible.

- Demonstrate efficient use of investigations and consultations in clinical care.

- Reflective discussions

- Encourage learners to reflect on the ethics of resource use and environmental impact as part of professionalism and systems-based practice.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Medical Educators

1. What core skills are most important for a successful career in medical education?

Key skills include:

- Clinical excellence and credibility in your field.

- Educational design and Teaching Strategies: curriculum development, assessment design, feedback delivery.

- Communication and facilitation: guiding discussions, handling challenging learner behaviors, and promoting Student Engagement.

- Leadership and change management: championing innovation, building consensus, and aligning educational initiatives with institutional goals.

- Reflective practice and Professional Development: regularly assessing your own teaching, seeking feedback, and engaging in scholarly Medical Education.

2. How can I stay updated with best practices in medical education and assessment?

Consider a layered approach:

- Read key journals: Academic Medicine, Medical Education, Medical Teacher, Advances in Health Sciences Education.

- Join professional organizations: AMEE, AAMC, regional GME/UME associations.

- Attend conferences and webinars focused on Medical Education and Healthcare Training.

- Use curated online resources: MedEdPORTAL, AAMC MedEdCONNECT, specialty society education sections.

- Engage in local faculty development workshops and communities of practice at your institution.

3. What are some high-yield, practical teaching strategies I can implement immediately?

You can start with:

- Brief “pause-and-question” moments in any lecture every 10–15 minutes to ask a clinical reasoning question or mini-case.

- Think–pair–share: give learners a question, let them think individually, discuss with a partner, then share with the group.

- One-minute preceptor technique during clinical encounters for rapid, structured teaching and feedback.

- Exit tickets: ask learners to submit one “muddiest point” at the end of a session to guide your next teaching.

4. How can I better support struggling learners without lowering standards?

- Early identification: use regular formative assessments and observation to detect difficulties early.

- Structured learning plans: co-create targeted remediation plans with clear goals, timelines, and support (e.g., skills labs, tutoring, coaching).

- Collaboration: involve program directors, learning specialists, and mental health professionals when needed.

- Documentation and transparency: keep clear records of concerns, interventions, and outcomes while treating learners with empathy and respect.

- Maintain standards: focus on supporting learners to meet existing competencies, not on lowering expectations.

5. How do I build a scholarly portfolio in medical education?

- Start small but systematic: turn innovations (new curricula, assessment tools, feedback methods) into scholarship by evaluating them.

- Use established frameworks: adopt models like Kern’s six-step curriculum design or Kirkpatrick’s evaluation framework when planning projects.

- Collect data: pre/post surveys, performance metrics, qualitative feedback.

- Disseminate: present at education conferences, submit to MedEdPORTAL or education journals, and track all outputs in a teaching portfolio.

- Seek mentorship: collaborate with experienced education scholars who can guide study design, IRB processes, and publication strategy.

Medical educators today work at the intersection of clinical excellence, educational science, and human development. By intentionally addressing these core challenges—staying current, engaging learners, balancing roles, embracing diversity, preventing burnout, improving assessment, aligning education with practice, and integrating sustainability—you can create transformative learning environments that prepare the next generation of healthcare professionals for a complex, rapidly evolving world.