Introduction: Why Educator Skills Matter in Modern Medical Education

Medical education is no longer just about delivering lectures or supervising ward rounds. It is a complex, rapidly evolving discipline where clinician-educators shape how future physicians think, communicate, and practice. As healthcare systems become more interdisciplinary, technology-driven, and patient-centered, the expectations placed on medical educators have expanded dramatically.

For aspiring medical educators—whether you are a medical student, resident, fellow, or early-career clinician—developing strong educator skills is now a core professional competency. You are not just teaching facts; you are helping learners develop clinical reasoning, professional identity, cultural competency, and habits of lifelong learning.

This comprehensive guide expands on the essential skills needed to succeed in medical education, with a focus on practical, real-world strategies you can start using immediately in academic, clinical, and simulation settings.

1. Mastering Effective Communication in Medical Education

Communication is the foundation of all successful teaching strategies. In medical education, it extends beyond explaining pathophysiology. It includes how you frame uncertainty, respond to errors, give feedback, and create psychological safety in learning environments.

1.1 Core Components of Effective Educator Communication

Clarity and structure

- Use plain language first, then add technical detail as needed.

- Chunk information into small, digestible segments (e.g., “3 key points,” “2 takeaways”).

- Summarize at the end of a teaching moment: “So the key points about sepsis in this patient are…”

Active listening

- Ask open-ended questions: “What’s your current understanding of this topic?”

- Allow silence; give learners time to think before jumping in.

- Reflect back what you hear: “So you’re worried that you’ll miss a subtle finding on exam—let’s walk through how to approach that.”

Non-verbal communication

- Maintain eye contact with all learners, not just the most vocal.

- Sit or stand at eye level with students when feasible to reduce hierarchy.

- Use open posture and nodding to signal encouragement and attentiveness.

1.2 Teaching Communication in the Clinical Environment

Clinical settings, especially on rounds or in the OR, can be high-pressure environments where communication breaks down easily.

Practical strategies:

- Use “teachable moments” on rounds

- After seeing a patient with new atrial fibrillation, pause briefly:

“In 60 seconds, what are the three big considerations when you see new-onset AF in the hospital?”

- After seeing a patient with new atrial fibrillation, pause briefly:

- Name your teaching

- Signal clearly when you’re switching from clinical decision-making to teaching:

“I’m going to step into teaching mode for 2 minutes to break down the approach to chest pain.”

- Signal clearly when you’re switching from clinical decision-making to teaching:

- Adapt to learner level

- Ask: “Are you comfortable if I pitch this explanation at a PGY-1 level and then build up?”

1.3 Communication Pitfalls to Avoid

- Using excessive jargon with early learners.

- Asking only “pimp-style,” high-pressure questions without explanation.

- Providing vague feedback like “good job” without specifics.

- Dominating the conversation and not checking for understanding.

Developing precision, empathy, and structure in your communication will significantly enhance your effectiveness as a medical educator.

2. Building Strong Pedagogical Competency and Teaching Strategies

Clinical expertise is necessary but not sufficient to be a great medical educator. You also need pedagogical competency—an understanding of how people learn, how to design teaching sessions, and how to choose appropriate teaching strategies for different goals and settings.

2.1 Fundamentals of Adult Learning in Medical Education

Most medical learners are adults or young adults, and adult learning theory (andragogy) offers useful principles:

- Adults are self-directed and want to know why they are learning something.

- They bring prior experience that can be used as a foundation.

- They are problem-centered, preferring practical, case-based learning.

- Motivation often increases when learning is clearly relevant to their goals.

Actionable tip: At the beginning of a session, briefly state:

- What you’re going to cover,

- Why it matters to their level of training,

- How it connects to their clinical responsibilities.

2.2 Key Teaching Strategies for Medical Educators

A strong educator skill set includes the ability to choose and mix strategies:

Lectures and interactive talks

- Still valuable for foundational concepts when done well.

- Use short didactic bursts (10–15 minutes) followed by questions or mini-cases.

- Incorporate polling tools (e.g., Poll Everywhere) to check understanding.

Small group discussions

- Ideal for developing reasoning, communication, and teamwork.

- Assign roles (case presenter, scribe, discussant) to keep everyone engaged.

- Use structured frameworks (e.g., SNAPPS, PICO, SOAP) to guide discussion.

Case-based and problem-based learning

- Present realistic clinical scenarios with progressive data disclosure.

- Encourage learners to generate differential diagnoses, management plans, and next steps.

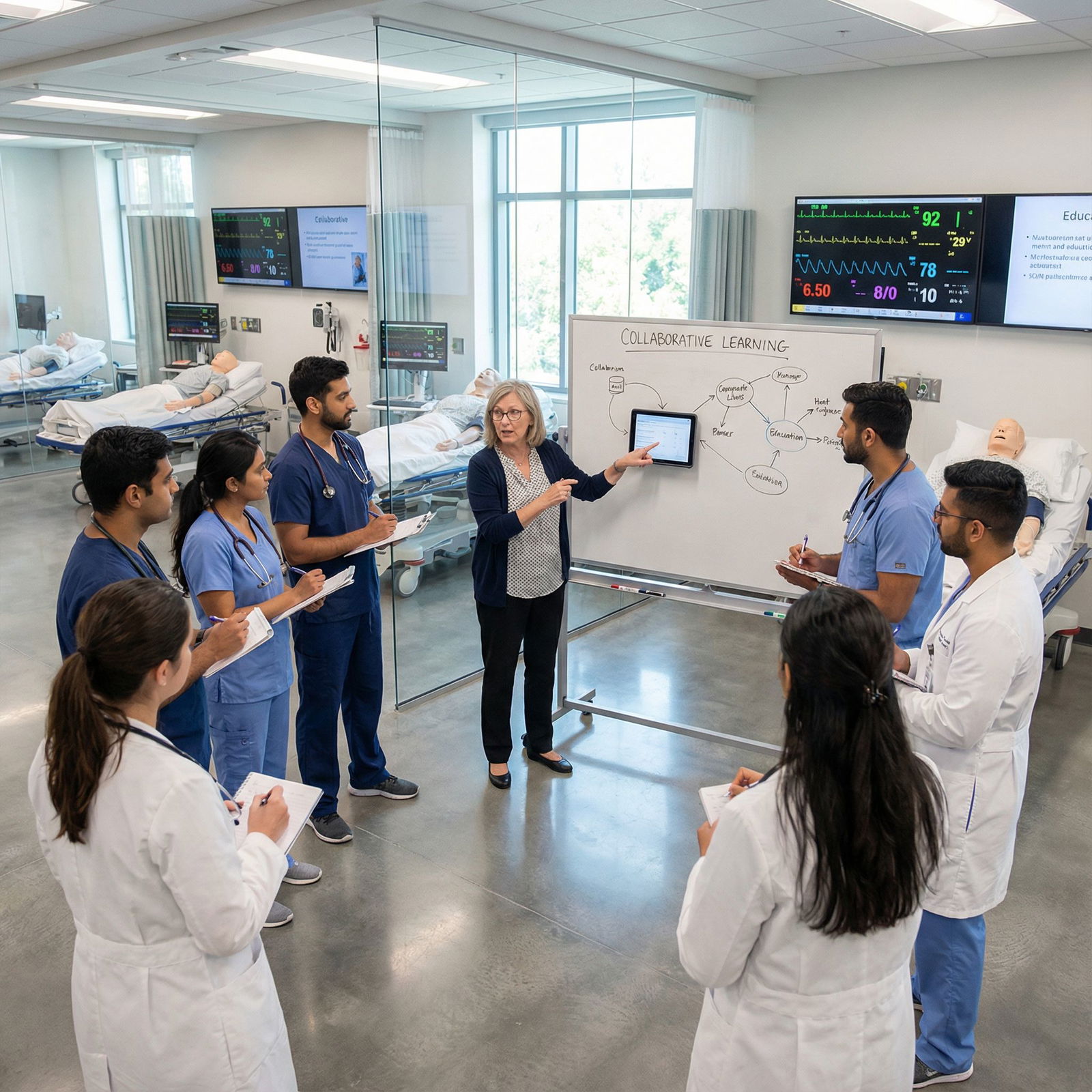

Simulation-based learning

- High-fidelity manikins, standardized patients, or virtual platforms.

- Excellent for procedural skills, communication, and crisis resource management.

- Always include a structured debrief—this is where most learning occurs.

2.3 Designing Educational Sessions with Intention

To enhance your educator skills, practice backward design:

Define learning objectives

- Use action verbs (e.g., “list,” “interpret,” “perform,” “counsel”).

- Example: “By the end of this session, learners will be able to formulate an initial management plan for septic shock.”

Select assessments

- Decide how you will know if objectives are met (questions, OSCEs, reflective writing, direct observation).

Plan teaching activities

- Choose strategies aligned with your objectives (e.g., simulation for procedures, role-play for breaking bad news).

By grounding your teaching strategies in clear objectives, you’ll create more purposeful, efficient, and impactful learning experiences.

3. Embracing Adaptability and Lifelong Learning as a Clinician-Educator

Medical knowledge doubles rapidly, and educational methods evolve alongside healthcare technologies and societal expectations. Thriving as a medical educator requires a commitment to lifelong learning—both clinically and pedagogically—and the flexibility to adapt your teaching accordingly.

3.1 Staying Current in Clinical Practice and Medical Education

Clinical updates

- Regularly review major journals in your specialty.

- Use point-of-care tools (e.g., UpToDate, DynaMed) not only for patient care but as teaching prompts: “Let’s check the latest guideline together.”

- Participate in morbidity and mortality conferences as learning opportunities.

Educational development

- Attend workshops on teaching skills, assessment, curriculum design, and educational scholarship.

- Consider formal training (e.g., certificate in medical education, Masters in Health Professions Education) if you envision a long-term educator track.

Professional organizations

- Join groups such as:

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC)

- American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine (AACOM)

- Specialty-specific education sections (e.g., Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors)

- These often provide teaching resources, webinars, and mentorship for educators.

- Join groups such as:

3.2 Adaptability in Teaching Contexts

Clinical and educational environments can change quickly—COVID-19-era shifts to virtual learning were a powerful example.

Ways to cultivate adaptability:

Flex between formats

- Be comfortable teaching in-person, hybrid, and fully online.

- Modify activities on the fly if time is cut short or clinical demands increase.

Adjust to learner needs

- Quickly assess learner level at the start:

“Tell me what you’ve seen so far with this condition and what you hope to get out of today.” - Adapt depth and pace based on their responses and engagement.

- Quickly assess learner level at the start:

Reflect and refine

- After a session, ask: “What went well? What would I change next time?”

- Seek feedback from learners and colleagues to inform your growth.

Lifelong learning and adaptability are not optional extras; they are core educator skills that allow you to stay relevant and effective throughout your career.

4. Developing Robust Assessment and Evaluation Skills

Assessment is where medical education meets accountability. Effective educators must be able to measure not only knowledge, but also skills, behaviors, and professional attitudes. Done well, assessment is a powerful teaching tool; done poorly, it can undermine motivation and trust.

4.1 Principles of High-Quality Assessment in Medical Education

- Validity: Does the assessment truly measure what you intend (e.g., clinical reasoning vs memorization)?

- Reliability: Are results consistent across learners, raters, and time?

- Fairness: Are assessments transparent, unbiased, and appropriate to the learner’s level?

- Feasibility: Is it realistic in your clinical or educational context?

4.2 Types of Assessment Tools and When to Use Them

Written exams

- Multiple-choice questions (MCQs) for breadth of knowledge.

- Short-answer or essay questions for depth and reasoning.

- Tip: Link every test item to a clear learning objective.

Performance-based assessments

- Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) for history-taking, physical exam, and procedural skills.

- Direct observation tools (e.g., Mini-CEX, Entrustable Professional Activities) for real-time assessment in clinical settings.

Workplace-based assessments

- Chart review, procedure logs, multisource feedback (peers, nurses, patients).

- Assess professionalism, teamwork, and communication.

Formative vs summative

- Formative: low-stakes, frequent, focused on growth and feedback (e.g., feedback after a patient encounter).

- Summative: high-stakes, used for promotion, certification, or progression.

4.3 Giving Effective Feedback: Turning Assessment into Learning

Feedback is one of the most powerful educator skills—and one of the hardest to master.

Effective feedback characteristics:

- Timely: As close to the observed behavior as possible.

- Specific: “Your explanation of risks was clear, but you skipped discussing alternatives.”

- Balanced: Highlight strengths and areas for improvement.

- Actionable: Offer concrete suggestions: “Next time, try starting with the patient’s main concern and then summarizing what you heard.”

Useful models:

Ask-Tell-Ask

- Ask the learner to self-assess.

- Tell your observations and suggestions.

- Ask how they will apply this next time.

Feedback sandwich (used thoughtfully)

- Positive comment → Constructive criticism → Positive reinforcement.

By treating assessment as part of teaching rather than a separate hurdle, you help cultivate a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety.

5. Leadership, Mentorship, and Role Modeling in Academic Medicine

Medical educators are inherently leaders. Whether you are leading a small tutorial, a night float team, or a curriculum committee, you influence culture, standards, and learner well-being. Effective educator skills therefore include leadership, mentorship, and intentional role modeling.

5.1 Leadership Skills for Medical Educators

Vision and alignment

- Articulate clear expectations for learners at the start of a rotation or course.

- Align your teaching and assessment with institutional goals and competencies.

Team management

- Create a respectful environment where questions and uncertainty are welcomed.

- Delegate responsibilities (e.g., having a senior resident teach a junior) to build leadership in others.

Conflict resolution

- Address issues early, whether between team members or between learners and supervisors.

- Use calm, private conversations to clarify expectations and perspectives.

5.2 Mentorship: Supporting Career and Personal Growth

Mentorship is a cornerstone of medical education and professional development.

Ways to be an effective mentor:

Clarify the relationship

- Agree on goals: “Are you mainly looking for help with research, career planning, or teaching skills?”

- Discuss how often you will meet and preferred modes of communication.

Advocate and sponsor

- Recommend mentees for presentations, committees, or leadership roles.

- Provide guidance on CVs, personal statements, and fellowship applications.

Model work-life integration

- Share realistic strategies you use to manage workload, stress, and personal commitments.

You can also participate in structured mentorship programs that pair junior faculty or residents with experienced educators, fostering a supportive and growth-oriented academic culture.

5.3 Role Modeling Professionalism and Lifelong Learning

Learners are always observing you—how you interact with patients, respond to uncertainty, admit mistakes, and handle stress.

Powerful ways to role model:

- Thinking aloud during clinical reasoning, including your doubts.

- Demonstrating respect for all team members, regardless of role.

- Owning and correcting your own errors, showing how to learn from them.

- Making your own lifelong learning visible (e.g., briefly sharing a recent article you changed your practice based on).

6. Leveraging Technological Proficiency in Modern Medical Education

Technology is now inseparable from both healthcare delivery and medical education. Effective educator skills include the ability to assess when and how digital tools enhance learning—and when they distract from it.

6.1 Core Educational Technologies for Medical Educators

Learning Management Systems (LMS)

- Platforms like Canvas, Blackboard, or Moodle.

- Use them to post resources, track assignments, run quizzes, and host discussion boards.

Digital simulation tools

- Virtual reality platforms and computer-based simulators for procedures and anatomy.

- Case-based simulation software for decision-making and teamwork.

Telehealth and virtual care

- Teach learners how to conduct virtual visits, including “webside manner.”

- Use screen sharing to demonstrate how to review labs or imaging with patients.

6.2 Integrating Technology into Teaching Strategies

Blended learning

- Provide brief pre-recorded microlectures or readings before in-person sessions.

- Use face-to-face time for discussion, clarification, and application.

Interactive tools

- Polling apps, online whiteboards, and breakout rooms for active participation.

- Digital quizzes for rapid formative assessment during or after sessions.

Digital professionalism

- Teach and model appropriate use of electronic health records.

- Address confidentiality, social media professionalism, and patient privacy.

Technology should serve educational goals, not the other way around. Regularly evaluate whether a tool is improving engagement and understanding or merely adding complexity.

7. Cultivating Cultural Competency and Inclusive Teaching Practices

Cultural competency is critical in both patient care and medical education. As an educator, you influence how learners understand and respond to diversity in patients, colleagues, and communities. Inclusive teaching is now recognized as a core educator skill.

7.1 Elements of Cultural Competency in Medical Education

Self-awareness

- Reflect on your own biases, assumptions, and cultural background.

- Be open about what you don’t know and model curiosity rather than judgment.

Knowledge of diversity in health and illness

- Address how culture, race, ethnicity, language, gender identity, sexual orientation, disability, and socioeconomic status affect health and healthcare access.

- Integrate this content across the curriculum, not just in one “diversity” lecture.

Skills in cross-cultural communication

- Teach learners to ask about patients’ beliefs, values, and preferences.

- Normalize the use of professional interpreters and teach how to work with them.

7.2 Practical Strategies for Inclusive Teaching

Inclusive curriculum design

- Use case examples that feature diverse patient populations and non-stereotyped roles.

- Avoid always framing certain groups only in the context of disease or disparity.

Equitable classroom practices

- Invite contributions from quieter learners explicitly.

- Set ground rules for respectful discussion of sensitive topics.

- Address microaggressions or biased comments promptly and professionally.

Assessment equity

- Review assessment tools for cultural and linguistic bias.

- Ensure all learners have equitable access to resources, mentorship, and opportunities.

By intentionally integrating cultural competency into your teaching strategies, you help prepare learners to deliver equitable, patient-centered care in a diverse society.

Conclusion: Charting Your Path as a Medical Educator

Becoming an effective medical educator requires far more than clinical expertise. It involves cultivating a broad suite of educator skills:

- Clear, empathetic communication that promotes understanding and psychological safety.

- Solid pedagogical competency and flexible teaching strategies tailored to learner level and context.

- Commitment to lifelong learning and adaptability in both clinical practice and educational methods.

- Thoughtful assessment and feedback that guide growth rather than just judge performance.

- Strong leadership and mentorship, with intentional role modeling of professionalism and curiosity.

- Strategic technological proficiency to enhance, not overshadow, learning.

- Deep cultural competency and inclusive teaching to prepare learners for diverse patient populations.

Whether you are just beginning to teach peers on the wards or aspiring to a career in academic medicine, you can start developing these skills now. Seek out teaching opportunities, ask for feedback, connect with experienced educators, and remain curious—not only about medicine, but also about how people learn.

Over time, your impact will extend far beyond individual encounters: you will shape how entire generations of clinicians think, practice, and care for patients.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Becoming a Medical Educator

1. What qualifications are typically needed to become a medical educator?

Most physician-educators hold an MD or DO (or equivalent international degree) and have completed residency training in a clinical specialty. However, meaningful involvement in medical education can begin much earlier.

Additional qualifications that strengthen an educator career path include:

- Teaching certificates from your institution’s faculty development programs.

- Formal training in medical education (e.g., Masters in Health Professions Education).

- Evidence of teaching excellence (evaluations, teaching awards, peer observations).

- Educational scholarship (curriculum development, education research, or published teaching tools).

Non-physician professionals (e.g., PhD scientists, advanced practice providers, pharmacists) also play major roles in medical education, often with discipline-specific degrees plus education-focused training.

2. How can I gain teaching experience if I’m still a student or resident?

There are many entry points into medical education even during training:

- Tutor junior students or peers in pre-clinical or clerkship courses.

- Lead review sessions, anatomy labs, or OSCE practice sessions.

- Volunteer to present at morning report, journal club, or case conferences.

- Collaborate with faculty on curriculum development projects.

- Serve as a teaching assistant or small-group facilitator if your school offers these roles.

- Join education committees, interest groups, or education tracks within your program.

Document these activities on your CV under “Teaching Experience” and seek feedback to continually refine your skills.

3. Are there certifications or formal pathways specifically for medical educators?

Yes. Depending on your region and institution, potential options include:

- Institutional faculty development certificates in teaching and learning.

- National or regional Academy of Medical Educators membership or certification.

- Specialty-specific educator tracks (e.g., clinician-educator pathways in internal medicine, pediatrics, surgery).

- Graduate programs such as:

- Master of Education (MEd) with a focus on health professions.

- Master of Health Professions Education (MHPE).

- Certificate programs in curriculum design, assessment, or simulation.

These credentials can enhance your skills, provide mentorship, and strengthen your competitiveness for academic positions.

4. What role does feedback play in effective medical education?

Feedback is central to learning and professional growth in medicine. Its key roles include:

- Helping learners understand their current performance relative to expectations.

- Identifying specific strengths to build upon and areas needing improvement.

- Guiding the development of individualized learning plans.

- Reinforcing a culture of continuous improvement and openness to critique.

As an educator, aim to provide frequent, specific, behavior-focused feedback, ideally based on direct observation. Encourage learners to seek feedback proactively and to reflect on how they will incorporate it into future practice.

5. How can I start integrating technology into my teaching without feeling overwhelmed?

Begin with small, purposeful steps:

- Use your institution’s LMS to organize materials and share key resources.

- Incorporate one interactive element into a lecture (e.g., a polling question, a short quiz).

- Try a brief pre-recorded microlecture that learners watch before an in-person case discussion.

- Collaborate with tech-savvy colleagues or your school’s instructional design team.

- Evaluate each new tool by asking: “Does this clearly improve learner engagement, assessment, or accessibility?”

Over time, you can expand your toolkit to include simulation, virtual patients, or advanced analytics—always guided by sound educational principles, not by technology for its own sake.

By intentionally cultivating these educator skills and teaching strategies, you position yourself to play a meaningful, lasting role in medical education—shaping not only competent clinicians, but also compassionate, reflective, and culturally competent professionals committed to lifelong learning.