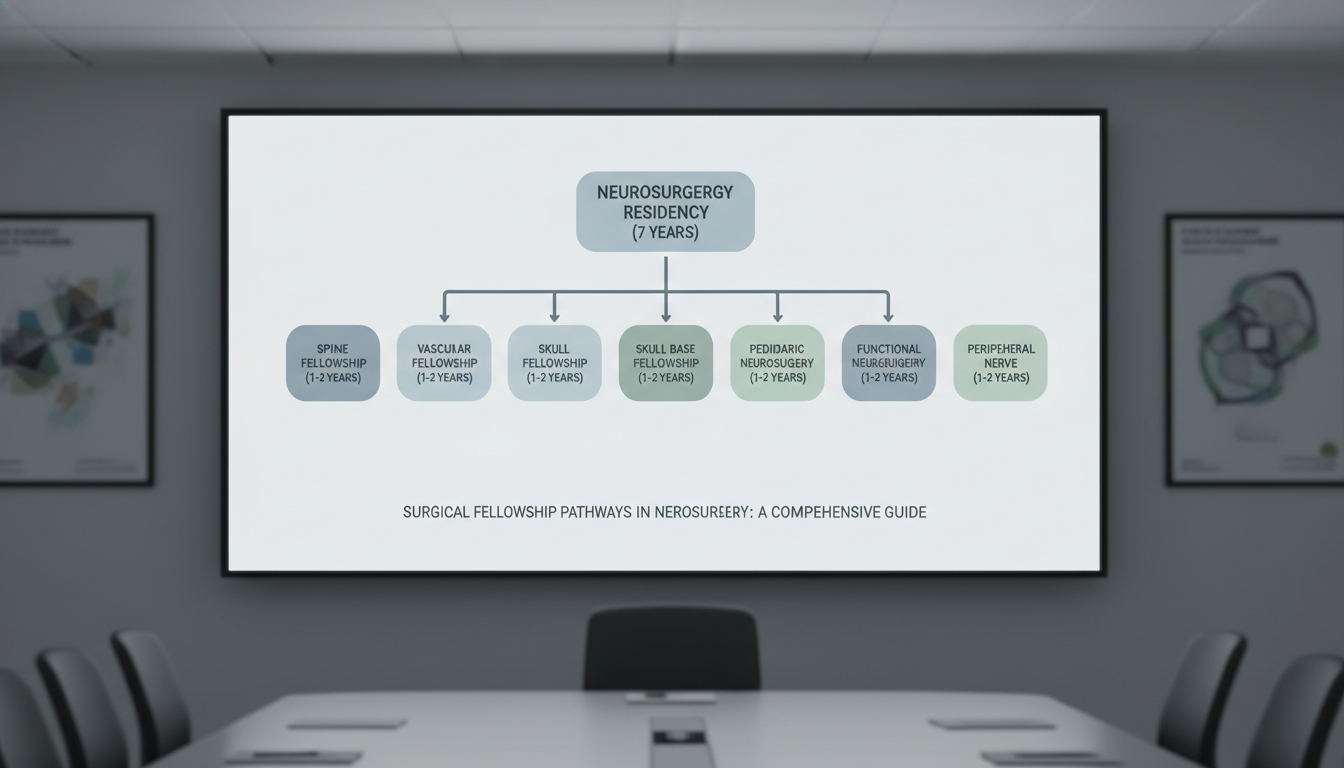

Understanding Surgical Fellowship Pathways in Neurosurgery

Neurosurgery residency is one of the longest and most demanding training pathways in medicine. Yet for many residents, completion of a neurosurgery residency is not the end of formal training. Subspecialty surgical fellowship pathways have become increasingly common, both to gain advanced operative skills and to remain competitive in academic and high-volume practice settings.

For neurosurgery residents interested in a brain surgery residency track with a strong subspecialty focus, understanding how surgical fellowships fit into training and career development is essential. This guide provides a comprehensive overview of neurosurgical fellowship pathways, timelines, subspecialty options, application strategies, and practical advice to help you plan your next steps.

1. Why Pursue a Surgical Fellowship After Neurosurgery Residency?

Neurosurgery residency is already a rigorous 7-year brain surgery residency (in most U.S. programs), so it is reasonable to ask: “Do I really need more training?” The answer depends on your career goals, case exposure, and target practice setting.

1.1 Common Reasons to Pursue a Fellowship

1. Subspecialty surgical expertise

Many modern neurosurgeons aim to focus their practice on a specific surgery subspecialty:

- Complex spine and deformity

- Vascular and endovascular neurosurgery

- Skull base and tumor surgery

- Pediatric neurosurgery

- Functional and epilepsy surgery

- Peripheral nerve

- Neuro-oncology and surgical oncology fellowship–type training

Fellowships provide high-volume exposure, advanced techniques, and refinement of microsurgical skills beyond what most residents achieve.

2. Academic and research career development

If you’re pursuing an academic career, fellowships can offer:

- Protected research time in a focused area (e.g., brain tumor biology, neuroimaging, device innovation)

- Advanced training in clinical trial design and outcomes research

- Mentorship from established subspecialty leaders

- Opportunities to build an early publication record in a niche domain

3. Competitiveness in the job market

In many regions and large centers, fellowship training is becoming the expectation rather than the exception for:

- Academic neurosurgery positions

- Complex subspecialty practices (e.g., skull base, endovascular)

- Leadership-track roles in multidisciplinary centers (comprehensive spine centers, cancer centers, epilepsy centers)

Community practices may be more flexible, but even there, fellowship training can differentiate you.

4. Confidence and autonomy

Extra focused training offers:

- Higher case volumes in complex procedures (e.g., aneurysm clipping, endoscopic skull base, complex deformity reconstruction)

- Gradual increase in operative autonomy with a second layer of supervision

- Improved comfort with high-risk decision-making and complication management

1.2 Situations Where Fellowship Might Be Less Critical

While fellowship pathways are valuable, they are not mandatory for everyone:

- You trained at a very high-volume program with robust exposure and graduated with strong operative numbers in your area of interest.

- You plan to practice as a general neurosurgeon in a community setting with a broad case mix.

- You wish to enter practice sooner due to personal, financial, or geographic considerations.

- Your chosen practice does not demand subspecialty certification (e.g., some general neurosurgery positions).

Still, even in these situations, a short fellowship (1 year) can refine skills and broaden your options later.

2. Overview of Major Neurosurgical Surgical Fellowship Pathways

Most neurosurgical fellowships are 1–2 years in length and focus on a single surgery subspecialty. Below is an overview of common pathways, typical structures, and how they align with different career goals.

2.1 Spine and Complex Spine Fellowship

Focus: Complex spinal reconstruction, deformity, revision surgery, spine oncology, and advanced minimally invasive spine.

Typical training elements:

- Adult deformity correction (scoliosis, kyphosis, sagittal balance)

- Revision spine surgery and management of failed back surgery

- Spinal oncology (intramedullary and extramedullary tumors, metastases)

- Advanced techniques: MIS TLIF/LLIF/ALIF, robotics, navigation, osteotomies

- Interdisciplinary collaboration with orthopedic spine, pain, and rehab

Best suited for:

- Residents who want a practice dominated by spine surgery

- Those seeking leadership roles in spine centers or multidisciplinary spine programs

- Residents whose residency spine volume was limited or unbalanced

2.2 Vascular and Endovascular Neurosurgery Fellowship

Focus: Cerebrovascular surgery and/or endovascular interventions. Some pathways are open vascular; others are dual-trained (open + endovascular).

Typical training elements:

- Open cerebrovascular: aneurysm clipping, AVM resection, bypass surgery, vascular malformations

- Endovascular: coiling, flow diversion, thrombectomy, stenting

- Stroke call and participation in comprehensive stroke center care

- Diagnostic angiography and advanced neuroimaging

Best suited for:

- Residents interested in stroke, aneurysms, vascular malformations, and critical care

- Those comfortable with high-risk, time-sensitive interventions

- Trainees considering academic roles in comprehensive stroke programs

Note: Endovascular pathways may involve interventional neuroradiology-type training, often with formal accreditation requirements and structured case logs.

2.3 Skull Base and Neuro-Oncology / Brain Tumor Fellowships

Focus: Complex skull base approaches and brain tumor surgery (including a “surgical oncology fellowship” flavor within neurosurgery).

Typical training elements:

- Microsurgical skull base approaches (transpetrosal, far lateral, extended approaches)

- Endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery and pituitary surgery

- Multidisciplinary tumor boards (neuro-oncology, radiation oncology, ENT)

- Advanced tumor resection techniques: fluorescence-guided surgery, awake mapping, intraoperative MRI/ultrasound

- Research in glioma, metastases, meningiomas, skull base tumors

Best suited for:

- Residents aiming for high-volume brain tumor and skull base practices

- Those targeting positions in NCI-designated cancer centers or academic tumor programs

- Applicants interested in clinical trials, translational research, or neuro-oncology leadership

This is commonly the closest neurosurgical equivalent to a surgical oncology fellowship, though it is often labeled “neuro-oncology” or “skull base” rather than oncology per se.

2.4 Pediatric Neurosurgery Fellowship

Focus: Comprehensive neurosurgical care for infants, children, and adolescents.

Typical training elements:

- Congenital anomalies: myelomeningocele, Chiari malformations, craniosynostosis

- Hydrocephalus management: shunting, endoscopic third ventriculostomy

- Pediatric brain and spinal tumors

- Pediatric epilepsy and functional procedures

- Trauma and critical care in pediatric populations

Best suited for:

- Residents passionate about long-term relationships with patients and families

- Those comfortable with family-centered decision-making and pediatric physiology

- Applicants targeting children’s hospitals and academic pediatric centers

Many pediatric neurosurgery fellowships have structured accreditation and board requirements.

2.5 Functional, Epilepsy, and Stereotactic Fellowship

Focus: Neuromodulation, movement disorders, epilepsy surgery, and stereotactic procedures.

Typical training elements:

- Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) for movement disorders and emerging indications

- Epilepsy surgery: temporal lobectomy, lesionectomy, stereo-EEG, RNS implantation

- Pain procedures: spinal cord stimulation, intrathecal pumps (in some programs)

- Image-guided and minimally invasive functional procedures (e.g., MR-guided focused ultrasound)

Best suited for:

- Residents interested in technology-intensive, multidisciplinary care

- Those drawn to long-term patient management with neurologists and neuropsychologists

- Candidates targeting academic epilepsy centers and movement disorder programs

2.6 Peripheral Nerve Fellowship

Focus: Surgical management of peripheral nerve injuries, entrapments, and tumors.

Typical training elements:

- Brachial plexus reconstruction and nerve transfers

- Entrapment neuropathies (carpal tunnel, cubital tunnel, etc.)

- Peripheral nerve tumors and plexus pathology

- Microsurgical nerve repair and grafting techniques

Best suited for:

- Residents who enjoy intricate microsurgery and reconstruction

- Those aiming for a niche practice within larger centers or combined ortho/plastic/neuro settings

2.7 Additional and Emerging Pathways

Some fellows pursue more specialized or combined tracks:

- Neurocritical Care (for neurosurgeons who want an ICU-based practice component)

- Spine Oncology / Complex Oncologic Spine Surgery (intersection of spine surgery and oncology)

- Innovation and Device Development (neurotechnology, neuromodulation, robotics)

- Global Neurosurgery (short- or long-term training with an emphasis on international neurosurgical care)

These can be stand-alone fellowships or combined with more traditional subspecialty training.

3. Timing, Structure, and Length of Neurosurgical Fellowships

Understanding when and how fellowships fit into your neurosurgery residency is critical for planning applications and career decisions.

3.1 When Do Neurosurgery Residents Apply?

Most residents start thinking seriously about fellowship in:

- PGY-4 / PGY-5: Clarifying subspecialty goals, building research portfolio, seeking mentorship

- PGY-5 / PGY-6: Actively applying and interviewing for fellowship positions

- PGY-7 (Chief Year): Finalizing contracts and planning transition

The specific timing can vary by subspecialty and region:

- Highly competitive fellowships (e.g., top vascular, skull base, endovascular) often recruit earlier.

- Some fellowships use formal match processes; others rely on direct applications and networking.

3.2 Length and Structure

Typical structures:

- 1-year clinical fellowship (most common)

- Intensive operative exposure

- Some research opportunities

- 2-year fellowship

- Year 1: Research or mixed research/clinical

- Year 2: Heavy clinical volume and operative cases

- Combined fellowships

- Example: 1 year of spine + 1 year of deformity or oncology focus

- Example: 1 year of open vascular + 1 year of endovascular

In certain regions, especially outside the U.S., training structures and titles may differ (e.g., “clinical attachment,” “senior registrar,” or “post-CCT fellowship”).

3.3 Accreditation and Certification Considerations

Important factors:

- Society-based accreditation: Some fellowships are recognized by neurosurgical societies (e.g., AANS/CNS sections, EANS).

- Pediatric neurosurgery and neurocritical care may have more formalized certification requirements.

- Endovascular training often follows structured pathways recognized by radiology and neurology organizations.

When evaluating fellowships, ask:

- Is this fellowship formally recognized or accredited by relevant neurosurgical bodies?

- Will this training fulfill credentialing expectations for my desired practice setting?

- How are graduates of this program perceived in the job market?

4. Choosing the Right Neurosurgical Fellowship for Your Career

Selecting a surgical fellowship pathway can feel overwhelming. A systematic approach will help align your choice with your long-term goals.

4.1 Clarify Your Long-Term Career Vision

Ask yourself:

- Do I want an academic or community practice?

- Do I see myself in high-volume subspecialty care or broad general neurosurgery?

- Which cases do I find most satisfying on call and in elective practice?

- How important are research, teaching, and leadership to me?

Examples:

- If you love complex spine, deformity conferences, and biomechanical problem-solving, a spine fellowship makes sense.

- If you thrive in the ICU and acute stroke environment, a vascular/endovascular path may be ideal.

- If you’re drawn to oncology, multidisciplinary tumor boards, and longitudinal patient care, consider a skull base/neuro-oncology or pediatric focus.

4.2 Evaluate Your Residency Training Gaps

Look critically at your case log and exposure:

- Did you have enough high-complexity cases in your area of interest?

- Did you have significant “primary surgeon” experiences or mostly assist roles?

- Are there specific technical skills (e.g., endoscopic skull base, deformity osteotomies, DBS) where you feel underprepared?

A fellowship should complement, not duplicate, your residency. Choose programs with clear added value.

4.3 Assess Fellowship Program Quality

When researching programs, consider:

Case volume and complexity

- How many cases per year will you participate in?

- What proportion will you be primary surgeon vs assistant?

- Are there marquee cases aligned with your goals (e.g., complex aneurysms, giant skull base tumors, pediatric craniofacial)?

Faculty and mentorship

- Are there well-known leaders who can mentor and advocate for you?

- Are faculty approachable and invested in fellows’ success?

- What are the recent fellows doing now (academia vs community, leadership roles)?

Educational environment

- Structured didactics, conferences, and case reviews?

- Opportunities for teaching residents and medical students?

- Simulation labs, cadaver courses, or industry-sponsored training?

Research opportunities

- Is there infrastructure for clinical and translational research?

- Are prior fellows publishing regularly during their fellowship?

- Are there funded projects you can join quickly?

Program culture and workload

- Reasonable call schedule and expectations?

- Support from residents, advanced practitioners, and multidisciplinary staff?

- Alignment with your values around wellness, equity, and teamwork?

4.4 Geographic and Lifestyle Considerations

Practical factors also matter:

- Proximity to family or support systems

- Cost of living and housing availability

- Spouse/partner career opportunities

- Visa requirements (for international applicants)

Because most fellowships are 1–2 years, some applicants tolerate less-than-ideal locations for exceptional training, but this trade-off should be consciously weighed.

5. Application Strategies for Neurosurgery Surgical Fellowships

Applying to neurosurgical fellowships is often more individualized and networking-driven than the neurosurgery residency or brain surgery residency match. Still, there are patterns and best practices.

5.1 Building a Competitive Fellowship Profile

From early residency onward:

- Clinical performance

- Strong operative skills and professionalism

- Positive reputation among attendings in your chosen subspecialty

- Research productivity

- Focused research in your area of interest (e.g., spine outcomes, aneurysm management, tumor genomics)

- First-author papers, abstracts, and presentations at related major meetings

- Networking

- Attend specialty conferences and section meetings (e.g., spine, vascular, tumor sections)

- Introduce yourself to potential fellowship directors and future colleagues

- Leadership and engagement

- Involvement in resident education, QI projects, or national neurosurgical committees

- Mentorship roles with junior residents or students

5.2 Components of the Fellowship Application

Typical components include:

Curriculum Vitae (CV)

- Up-to-date and tailored to highlight subspecialty experiences

- Clear sections for research, presentations, and awards

Personal Statement

- Focused on your subspecialty interest and long-term career goals

- Reflects insight into the field and what you hope to gain from fellowship

- Demonstrates fit with that specific program’s strengths

Letters of Recommendation

- 2–4 letters, ideally from:

- Subspecialty attendings in your area of interest

- Program director or chair

- Collaborators on key research projects

- Letters should describe your operative skills, judgment, work ethic, and collegiality

- 2–4 letters, ideally from:

Case Logs and Metrics

- Some fellowships request case logs to understand your baseline experience.

Interviews

- May be in-person or virtual

- Often include case-based discussions, assessment of your technical judgment, and exploration of your research interests

5.3 Interview Preparation and Performance

Key strategies:

Know the program

- Review faculty interests, recent publications, and typical fellow case mix

- Understand what makes the program unique (e.g., endovascular volume, complex deformity referrals)

Articulate your goals

- Be able to explain why this specific surgery subspecialty and why this program

- Connect the fellowship to your envisioned 5–10-year career plan

Discuss your experience honestly

- Be transparent about your current skill level and training gaps

- Emphasize your readiness to learn and capacity for growth

Ask thoughtful questions

- About operative autonomy, mentorship, research expectations, and graduate outcomes

- About how fellows are evaluated and supported

Professionalism and fit

- Programs want colleagues they trust in challenging OR and ICU scenarios

- Demonstrate maturity, humility, and team orientation

6. Transitioning from Fellowship to Practice

Your fellowship is both a capstone to your formal training and a bridge into independent practice. Planning this transition early will smooth your pathway.

6.1 Job Search Timing

Many neurosurgery fellows begin job searching:

- Late in residency or early in fellowship for highly competitive academic posts

- Midway through fellowship for most community and many academic positions

Steps:

- Update your CV and prepare a targeted cover letter

- Connect with mentors at your home and fellowship institutions

- Attend national meetings where hiring groups often recruit

6.2 Position Types After Fellowship

Common pathways:

Academic Subspecialty Surgeon

- High-volume subspecialty practice (e.g., spine, vascular, tumor)

- Expected to publish, teach, and contribute to program development

Hybrid Academic-Community Role

- Some protected time for teaching/research but substantial clinical load

- May be based at academic affiliates or regional campuses

Community Subspecialty or General Neurosurgeon

- Mix of general neurosurgery with varying degrees of subspecialty focus

- Emphasis on access to care, productivity, and local referral networks

6.3 Leveraging Your Fellowship Experience

You can maximize the impact of your surgical fellowship training in several ways:

- Develop a niche

- Within your subspecialty, focus on a particular area (e.g., deformity, endoscopic skull base, pediatric epilepsy) that distinguishes you.

- Build multidisciplinary programs

- Work with neurology, oncology, radiology, and rehab to create centers of excellence.

- Continue research and quality improvement

- Carry forward projects from fellowship, maintain collaboration with your mentors, and expand into your new environment.

- Mentor the next generation

- Use your fresh training experience to guide residents and students interested in similar pathways.

FAQs: Surgical Fellowship Pathways in Neurosurgery

1. Is a fellowship mandatory after neurosurgery residency?

No. Many neurosurgeons enter practice directly after a neurosurgery residency or brain surgery residency, especially into general or community positions. However, fellowship training is increasingly common—and sometimes expected—for highly specialized academic roles, high-complexity surgical practices, and competitive urban markets.

2. How do I decide between multiple subspecialty interests (e.g., spine vs skull base)?

Start by reviewing your operative experiences, rotation evaluations, and what you enjoy during call. Seek honest feedback from mentors in each area. Consider the long-term lifestyle, call patterns, and job markets in each surgery subspecialty. If you still remain undecided, focus on the area where your skills, passion, and available mentorship are strongest.

3. Can I complete more than one neurosurgical fellowship?

Yes, some neurosurgeons complete sequential fellowships (e.g., open cerebrovascular followed by endovascular, or spine followed by a spine oncology-focused surgical fellowship). However, extended training delays entry into practice and may not always provide proportional career advantages. Decide based on clear, added value and your long-term goals.

4. How does a neurosurgical fellowship compare to a surgical oncology fellowship?

A traditional surgical oncology fellowship is usually pursued after general surgery residency and focuses on broad oncologic surgery (GI, breast, sarcoma, etc.). In neurosurgery, analogous oncology-focused pathways include neuro-oncology and skull base/brain tumor fellowships, or spine oncology for metastatic and primary spinal tumors. These fellowships offer oncologic principles within the neurosurgical domain, often in tight collaboration with medical and radiation oncology.

By understanding the structure, options, and strategic value of surgical fellowship pathways in neurosurgery, you can align your post-residency training with the career you envision—whether that is in complex spine reconstruction, advanced brain tumor surgery, pediatric neurosurgery, vascular and endovascular care, or other subspecialty domains. Thoughtful planning, early mentorship, and targeted preparation will position you to make the most of this critical next step.