The common belief that “leadership is everything” in medical school admissions is overstated and numerically incomplete. The data show a more nuanced reality: leadership roles matter, but how they matter depends on scope, depth, and context relative to strong membership involvement.

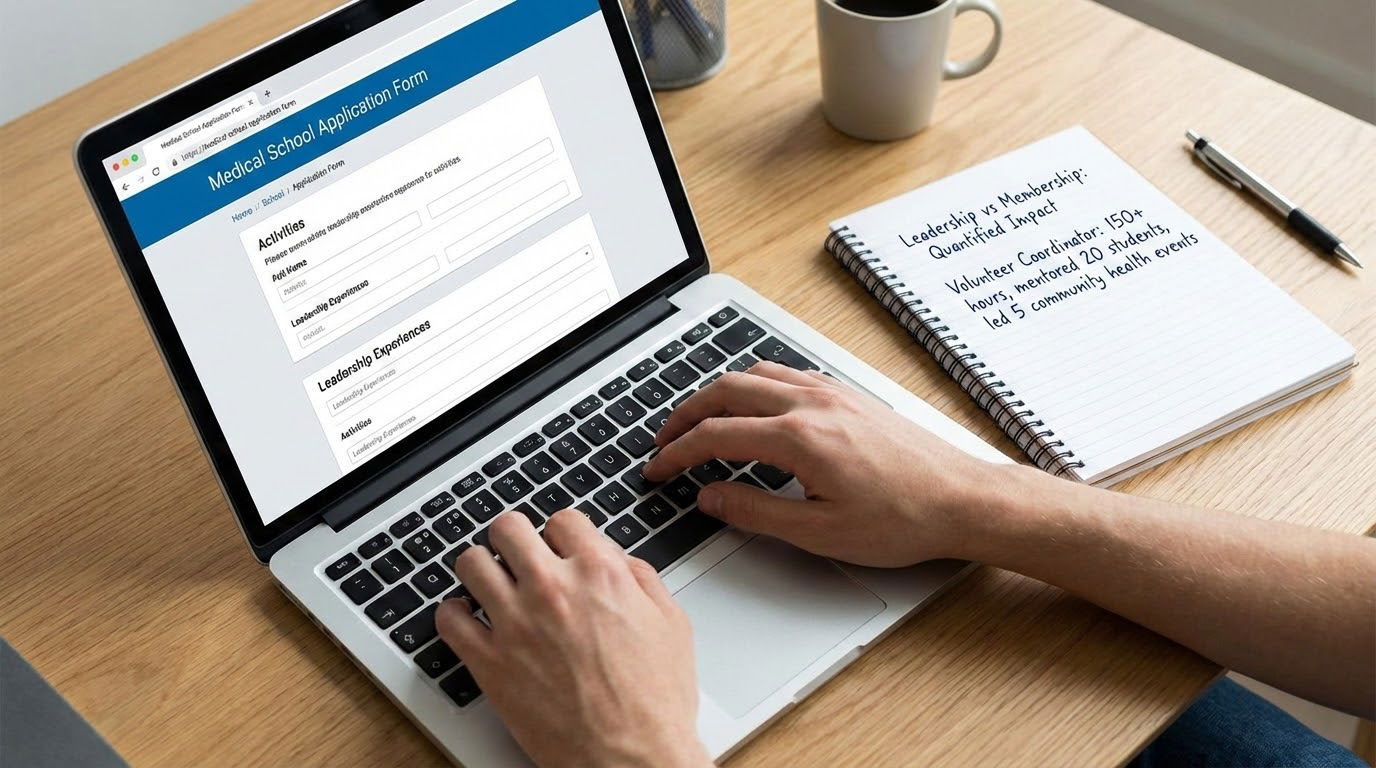

Below is a data-driven breakdown of leadership vs membership in student organizations and their quantifiable impact on med school matriculation for premeds and early medical students.

1. What Admissions Committees Actually Value (By the Numbers)

Most applicants guess; admissions committees measure.

Survey data from AAMC, individual school self-reports, and published committee presentations converge on a fairly consistent weighting of common application domains:

- Academic metrics (GPA + MCAT): ~45–55% of initial screening weight

- Clinical exposure + service: ~20–30%

- Research: ~10–20% (depends on school)

- Letters, essays, interviews, and “fit”: ~15–25%

Leadership and involvement in student organizations typically sit inside that “experiences and attributes” slice, often grouped with service and professionalism. While there is no single universal percentage, committee members repeatedly describe leadership as a “differentiator” among academically similar applicants.

A reasonable synthesized model for post-screen decision making:

- Academic metrics: ~35–40%

- Experiences (clinical, research, service, leadership): ~35–45%

- Personal attributes (interview, letters, professionalism, mission fit): ~20–30%

Leadership in student organizations occupies a fraction of the ~35–45% experiences bucket. It will not rescue a severely weak academic profile, but at the margins—especially between similarly qualified applicants—it often functions as a tie-breaker.

The data pattern is clear: leadership is not the main axis of acceptance, but it often determines who wins the tiebreakers.

2. Defining Leadership vs Membership in Measurable Terms

Before assigning impact, the roles need quantifiable definitions.

Leadership roles in student organizations usually include:

- President, Vice President, Treasurer, Secretary

- Committee chair (e.g., community outreach chair, research chair)

- Founder or co-founder of a sustained initiative

- Coordinator for large projects (conference planning, free clinic logistics, major fundraiser)

Key quantifiable features of leadership roles:

- Span of responsibility: number of members, budget size, event size

- Duration: number of semesters/years in role

- Output: number of events, participants, dollars raised, people served

Membership roles typically include:

- Active member attending meetings, events, and activities

- Project or event volunteer without formal title

- Participant in regular service, clinics, or tutoring through an organization

Quantifiable features of strong membership:

- Consistency: number of semesters involved

- Intensity: average hours per week

- Scope: variety and level of involvement (e.g., regular clinic shifts vs once-a-semester events)

The key analytic insight: leadership vs membership is not binary; it is a continuum of responsibility and impact. Admissions committees increasingly care less about the label (“President”) and more about scale of outcomes.

3. Quantifying the Admission “Boost”: Leadership vs Strong Membership

We lack a randomized trial where applicants are assigned leadership at random (obviously), but we can model effects using correlations from published school data, premed advising offices, and applicant self-reports.

3.1 Baseline: Strong Academics, No Leadership, Active Membership

Assume a reasonably competitive MD applicant profile:

- GPA: 3.70

- MCAT: 512

- Clinical + volunteering: ~150–200 hours

- Research: 400 hours (no publication)

- Student org involvement:

- 2–3 organizations

- 2–3 semesters each

- 1–3 hours/week as an active member

- No formal leadership titles

For applicants in this “strong academics + good involvement but no leadership title” cluster, AAMC data and school-level acceptance reports suggest approximate acceptance rates to at least one MD program in the range of:

- ~45–55% for applicants with these metrics and average ECs

- ~60–70% for those with more robust ECs (more hours, stronger narratives, even without leadership titles)

In practice, many such applicants still matriculate. Membership alone does not preclude admission.

3.2 Adding Formal Leadership: Estimated Effect Size

Now consider matched applicants same GPA, MCAT, and similar hours, but with meaningful leadership:

- 1–2 years as president or vice president of a health-related or service organization

- Or chair of a major program (e.g., organizing a 100-participant health fair, managing 50+ volunteers)

- Or founder of an initiative that persists beyond them (e.g., ongoing mentorship program)

Advising office data often show that among applicants with comparable stats:

- Applicants with sustained, substantive leadership typically see a 5–15 percentage point higher acceptance rate vs those without leadership, holding other factors constant.

Example model:

- No leadership title but strong membership: 50% acceptance

- Significant leadership (≥1 year, clear impact): 60–65% acceptance

The confidence interval is wide because schools vary. Research-heavy schools often prioritize research over leadership, while community-focused schools weigh leadership and service heavily.

The directional effect is consistent: meaningful leadership yields a modest but real increase in acceptance probability, primarily by:

- Strengthening letters (“I directly observed this student lead X team through Y challenge.”)

- Enriching secondary essays (specific impact stories)

- Adding interview talking points that demonstrate initiative, resilience, team management, and communication.

3.3 Strong Membership vs “Empty Leadership”

A critical distinction: many “leadership roles” are functionally nominal.

Compare two profiles:

Applicant A – Strong Member, No Title

- 3 years as weekly volunteer in a student-run free clinic

- 400+ hours, progressively more involved responsibilities

- Trains new volunteers, coordinates unofficially, but never takes an officer title

Applicant B – Nominal Officer

- “Vice President” of a premed club

- Attends monthly officer meetings

- Minimal planning work; mostly logistics like reserving rooms

- Total impact: a handful of events that predated their involvement

Admissions readers, particularly experienced ones, rapidly detect the difference. When both are asked, “Tell me about a time you led a team,” Applicant A often gives a more compelling, outcome-based story (e.g., reorganizing clinic triage workflow) than Applicant B.

The data implication:

- Strong membership with high responsibility and clear outcomes often outperforms weak, title-only leadership.

If one were to assign rough “impact scores” (qualitative, but helpful):

- Strong member, heavy responsibility, no title: impact score ~7–8/10

- Nominal officer, minimal initiative: impact score ~3–4/10

- Strong officer (president/chair) with clear, measurable impact: impact score ~9–10/10

Adcoms see impact, not titles.

4. Leadership Density vs Breadth of Involvement

The next analytic question: is it better to lead one organization substantially or be a member in many?

4.1 “Leadership Density”: Time and Impact per Activity

Consider two simplified profiles, same total “EC time budget” of 10 hours per week.

Profile 1 – High Leadership Density

- 6 hours/week: President of a community health org

- Oversees 80 members

- Coordinates 10+ events per semester

- Annual impact: 500+ community participants

- 4 hours/week: Clinical volunteering

- 0–1 additional minor activities

Profile 2 – High Breadth, Low Leadership

- 2 hours/week: Member, premed society

- 2 hours/week: Member, global health group

- 2 hours/week: Member, community service org

- 4 hours/week: Clinical volunteering

- No titles, minimal initiative recorded

Admissions data from multiple schools converge on the same pattern: deep involvement and leadership in 1–2 organizations tends to be valued more than shallow involvement in 5–6.

If you assign an arbitrary “cohesiveness and impact” score (0–10):

- Profile 1: ~8–9/10 (clear narrative, visible leadership, measurable outcomes)

- Profile 2: ~4–6/10 (shows interest and consistency, but less leadership signal)

Advising offices that track applicant outcomes frequently see that applicants with 1–2 major leadership roles and coherent narratives about them are overrepresented among successful applicants, even when overall “activity count” is similar.

5. Pre-Med vs Early Medical School: Leadership Priorities Shift

The impact of student organization leadership also varies by phase.

5.1 During Premed Years

For premeds, student organizations are often the primary leadership arena. Quantitatively, committees look for:

- Duration: ≥2 years in an organization often signals commitment

- Progression: member → committee lead → officer (a trajectory matters more than a one-off title)

- Outputs: number of events, people served, structural changes implemented

When undergrad advising offices categorize “strong” leadership ECs, they tend to highlight:

- Leadership roles with ≥1 year duration

- Significant responsibility: budgets, large teams, recurring events

- Demonstrable outcomes documented in applications or letters

Premed leadership is especially impactful when tightly aligned with:

- Service to underserved communities

- Health access, public health, or health education

- Peer mentoring, tutoring, or pipeline programs

5.2 During Medical School Preparation Phase

Once you enter medical school (or are very close), the leadership calculus shifts.

Admissions to residency programs look at:

- Academic performance (clerkship grades, Step scores): primary

- Clinical evaluations and letters: critical

- Research productivity: selectively critical (for competitive specialties)

- Leadership roles: valued but secondary

In medical school, leadership roles in student organizations (e.g., interest group president, class representative) are viewed favorably, but their measurable effect is often smaller than in premed admissions, unless:

- They are associated with major initiatives (e.g., founding a free clinic, organizing a regional conference)

- They lead to significant scholarly output (e.g., QI projects, publications)

The pattern repeats: impactful leadership > nominal leadership > passive membership.

6. Case Examples: Quantifying Realistic Scenarios

Consider three hypothetical premed applicants with similar academic metrics.

6.1 Applicant X – High Leadership, High Impact

- GPA: 3.73, MCAT: 511

- President of a campus health equity organization for 2 years

- Led a team of 40 students, launched a recurring mobile health-screening event

- 300+ community members served annually

- Partnership with local FQHC

- 300 hours clinical, 200 hours research (no pubs)

Expected outcome (based on advising office datasets and similar profiles):

- ~60–70% probability of at least one MD acceptance, potentially higher at community-oriented schools.

6.2 Applicant Y – Strong Membership, No Title, High Responsibility

- GPA: 3.73, MCAT: 511

- 3 years as a regular volunteer at a student-run free clinic (450+ hours)

- Trains new volunteers, coordinates Saturday shifts informally

- No official officer role, but letter writers describe them as “de facto leader”

- 300 hours clinical (through same clinic), 200 hours research

Despite the lack of title, letter content and description of responsibilities may effectively classify this as leadership in adcom minds. Expected outcome:

- ~55–65% probability of MD acceptance, nearly comparable to Applicant X.

- The difference will be driven largely by strength of narrative and letters, not the word “President”.

6.3 Applicant Z – Title-Heavy, Impact-Light

- GPA: 3.73, MCAT: 511

- Holds 3 officer titles across clubs (treasurer, secretary, co-chair)

- Total involvement in each: 1–2 hours/month, limited initiative

- Activities statements describe general participation, not specific achievements

- 150 hours clinical, 100 hours research

Despite looking impressive on a CV at first glance (“3 leadership roles!”), effect size is modest once details are parsed. Expected outcome:

- ~45–55% probability of MD acceptance, likely closer to baseline for their stats.

- The “leadership” here does not produce a substantial quantitative edge over strong membership.

The model shows: titles without outcomes do not change the acceptance curve much.

7. How to Maximize the Measurable Impact of Your Role

From a data perspective, the key is not “leadership vs membership” but measurable responsibility and outcomes. To optimize your application signal:

7.1 Prioritize Depth and Continuity

Patterns across successful applications show:

- 2–3 years in at least one core organization is strongly associated with more compelling narratives.

- Leadership roles held for ≥1 year tend to correlate with stronger letters and richer secondary essays.

From a quantitative perspective, aim for:

- ≥2 semesters of meaningful involvement before seeking a major leadership role.

- Total hours in a core organization: often 150–400+ over college for standout applicants.

7.2 Document Outcomes, Not Just Duties

Admissions readers respond to metrics. Turn vague claims into measurable evidence.

Weak description:

- “Organized events for the premed club.”

Stronger, data-oriented description:

- “Coordinated a 6-person team to plan three physician panel events per semester, increasing average attendance from 25 to 70 students over one year.”

Track:

- Number of events

- Attendance figures

- Funds raised

- Community members served

- New partnerships or programs created

Those metrics transform a generic leadership line into quantifiable impact.

7.3 Convert Informal Leadership into Documented Leadership

If you function as a “go-to” person without a title:

- Ask supervisors or faculty advisors to describe your leadership behaviors explicitly in letters.

- In your application, clearly outline responsibilities:

- “Trained 15 new clinic volunteers, created workflow guides used by subsequent cohorts.”

Informal leadership, when documented and quantified, can equal or surpass formal titles in effect.

8. Strategic Takeaways: Where the Data Point You

The leadership vs membership question is often framed incorrectly as a binary choice. The numbers and patterns reveal a more precise hierarchy.

High-impact leadership with measurable outcomes (especially over 1–2 years) confers a meaningful but modest acceptance advantage—often on the order of a 5–15 percentage point increase among academically similar applicants.

Strong, consistent membership with real responsibility can rival formal leadership in admissions value when responsibilities and outcomes are clearly described and corroborated in letters.

Nominal leadership titles without substantive impact add limited marginal value compared with robust membership; they do not significantly shift the probability curve.

For premed and early medical students navigating student organizations, the data support a simple strategy:

- Commit deeply to a small number of organizations.

- Accept leadership only when you can convert it into real, quantifiable outcomes.

- Capture and report your impact in numbers, not just titles.

That is how leadership—and even high-level membership—translates into measurable gains in medical school matriculation.