How to Tackle Red Flags in Residency Applications: Navigating Your Bumps and Bruises

Residency Applications are stressful for everyone, but for applicants with perceived “red flags,” the process can feel especially daunting. Whether you’re worried about a low Step score, a gap in training, or a program dismissal, it’s important to remember: many residents and attendings practicing today matched successfully despite serious bumps in their application.

This guide walks you through what counts as a red flag, how programs think about them, and practical Application Strategy steps to address them in ERAS, letters, and interviews—while still presenting yourself as a strong, resilient, and self-aware candidate.

What Are Red Flags in Residency Applications?

In the context of Medical Education and Career Development, a “red flag” is any feature of your application that may raise concern about your readiness, professionalism, reliability, or long-term success in residency.

Program directors differ in how much weight they assign to each issue, but common Red Flags include:

Gaps in Education or Training

- Unexplained time away from medical school or clinical activity

- Long periods without clinical exposure or work

Low Academic Performance

- Failing or very low scores on USMLE/COMLEX

- Failed courses or clerkships

- Repeated years of medical school

Changing Specialties or Unclear Career Direction

- Applying to a new specialty after investing heavily in another

- ERAS application that seems inconsistent with your new specialty choice

Inconsistent Work or Clinical History

- Short-term, fragmented positions

- Multiple observerships or externships without progression

Negative Evaluations or References

- Poor narrative comments in MSPE or clerkship evaluations

- Letters of recommendation that are lukewarm or subtly negative

Professionalism, Conduct, or Academic Integrity Issues

- Remediation for professionalism concerns

- Honor code violations, plagiarism, or disciplinary actions

Incomplete or Disorganized Applications

- Missing documents, late submissions, sloppy errors

- Unexplained omissions (e.g., missing attempts at licensing exams)

Withdrawals, Leaves of Absence, or Dismissals

- Leaving a prior residency program

- Dismissal or non-renewal of contract

- Prolonged leaves without context

Not every imperfection is a red flag. A single mid-range exam score, one average rotation, or a minor delay rarely disqualifies you. Red flags become most concerning when they:

- Suggest patterns (repeated failures, repeated professionalism issues)

- Are unexplained or poorly addressed

- Conflict with the specialty’s core demands (e.g., poor interpersonal skills for psychiatry, repeated professionalism issues for any specialty)

The first step is honest self-assessment: identify the potential red flags in your file so you can address them deliberately instead of hoping programs won’t notice.

General Principles for Managing Red Flags

Before diving into specific situations, it helps to understand how program directors often think about risk and mitigation.

How Programs View Red Flags

Program leadership typically asks:

What actually happened?

Is the problem academic, professional, personal, or logistical?Is this a one-time event or a pattern?

A single failed Step exam with later strong performance is very different from repeated failures.Has the applicant clearly learned and grown?

Can you demonstrate insight, maturity, and concrete changes in behavior or strategy?What objective evidence shows improvement?

Better grades, strong recent clinical evaluations, improved exam performance, consistent work, and strong letters help mitigate concerns.Can this risk harm patients, the team, or the program?

Red flags tied to professionalism, integrity, or patient safety are usually more serious than purely academic issues.

Your job is to help programs answer these questions clearly and positively.

Core Strategies That Apply to Almost All Red Flags

Be honest, but concise.

Trying to hide or distort facts usually backfires. Brief, factual explanations plus a focus on growth are usually best.Take responsibility where appropriate.

Avoid blaming others or sounding defensive. Own your part, then show what you changed.Shift the focus to your recovery and resilience.

Highlight actions you took afterward: tutoring, counseling, improved study strategies, additional clinical experiences, etc.Use multiple parts of your application to reinforce your narrative.

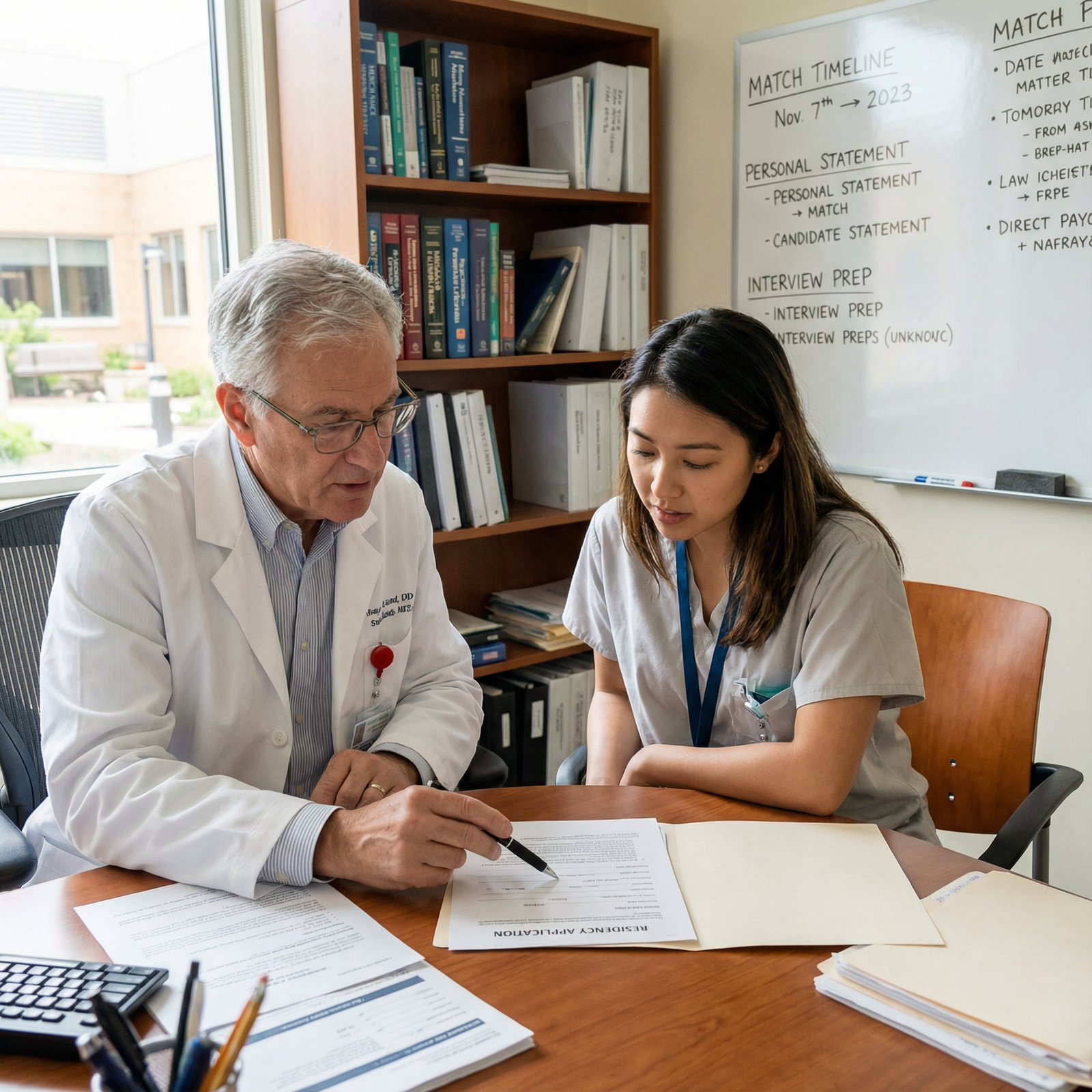

Personal statement, experiences section, MSPE addendum (if applicable), and letters of recommendation should all align to tell a coherent story of growth.Get external feedback early.

Ask a trusted advisor, dean, or mentor to review your application for potential concerns and help craft explanations.

Specific Red Flags and How to Address Them Effectively

1. Gaps in Education or Clinical Activity

Time away from training is not automatically fatal to your application, but unexplained gaps are.

Examples of gaps:

- A year off between M2 and M3

- Several years between graduation and application (common for IMGs)

- Months without clinical activity after a prior residency or job

How to Tackle:

a. Provide clear, honest context

Use one brief, well-placed explanation rather than multiple scattered references. Depending on the situation, this may go in:

- Your personal statement (1–2 concise sentences)

- The “Additional Information”/“Explain” section in ERAS

- A dean’s letter/MSPE comment, if allowed

Effective framing:

- “During my third year, I took a one-year leave of absence to address a significant family health crisis. During this time, I maintained engagement with medicine through [online coursework, research, part-time clinical work where appropriate]. Returning to school, I was able to…”

- “After graduation, visa and financial constraints required me to work temporarily outside of clinical medicine; during that time, I pursued [research, certifications, observerships] to remain connected to clinical care.”

b. Demonstrate continued engagement with medicine

Programs want proof you are still clinically sharp and committed. Consider:

- Recent observerships, externships, or clinical jobs

- Certification or recertification in BLS/ACLS

- Continuing medical education (CME) activities or online coursework

- Recent research or quality improvement projects

c. Highlight successful re-entry

If you have already returned to training or clinical work:

- Emphasize strong clinical evaluations after the gap

- Ask recent supervisors to explicitly comment on your reliability, clinical performance, and ease of reintegration

2. Low Academic Performance or Exam Scores

Academic struggles are common, especially with the transition to clinical training and high-stakes board exams. Program directors care less about the raw score than about what it predicts and whether you improved.

Common scenarios:

- Failing USMLE Step 1, Step 2 CK, or COMLEX

- Low but passing exam scores compared to your specialty’s norms

- Remediated pre-clinical courses or clerkships

- Repeating a year of medical school

How to Tackle:

a. Show an upward trend

Program directors value trajectory:

- Improved exam performance on later attempts or on subsequent exams

- Strong performance on NBME shelf exams, subject exams, or in-clinic assessments

- Honors or high passes in later clinical rotations

Make these trends explicit in your personal statement or interviews:

“Although I initially struggled with standardized exams and failed Step 1 on my first attempt, I sought guidance from academic support services, adopted a structured study schedule, and worked with a tutor. These changes led to a passing score on my second attempt and a significantly stronger performance on Step 2 CK, where I scored [X], closer to the average for my chosen specialty.”

b. Convert a weakness into a catalyst for growth

Describe what changed:

- Study techniques (active recall, spaced repetition, question banks)

- Time management and prioritization

- Stress management, sleep, and wellness strategies

- Use of institutional resources (learning specialists, tutoring, counseling)

c. Consider additional academic work when appropriate

For applicants with more extensive academic problems, consider:

- A structured research fellowship with strong mentorship and academic output

- A transitional or preliminary year in a less competitive specialty with strong clinical performance

- Post-baccalaureate or graduate coursework (particularly if you’re very early in training, such as pre-med or early MD/DO)

These options should demonstrate capability and consistency, not merely add lines to your CV.

3. Changing Specialties or Appearing Indecisive

Switching specialties is more common than you think. Program directors worry less about the mere change and more about whether you:

- Understand your new specialty deeply

- Can explain your decision clearly and authentically

- Have relevant experiences and letters to support your new direction

How to Tackle:

a. Tell a coherent Career Development story

In your personal statement and interviews, address:

- What initially drew you to the original specialty

- What experiences led you to reconsider

- What concrete exposures convinced you the new specialty is a better fit

- How your skills and interests align with the demands of the new field

Avoid framing your change as simply “I couldn’t match into X, so I chose Y instead.” Instead:

“During my sub-internship in internal medicine, I realized that what I enjoyed most was the continuity of care, longitudinal relationships, and managing chronic diseases in the outpatient setting. Over time, I saw that my strengths in communication and preventive care aligned more with family medicine’s broad scope. After this realization, I pursued additional clinic-based electives and mentorship in family medicine, confirming my decision.”

b. Highlight transferable skills

Show how your previous focus enhances your new path:

- A former surgical applicant to anesthesia: manual dexterity, OR familiarity, acute care mindset

- A former pediatrics applicant to family medicine: child health experience, communication with families

- A former IM applicant to psychiatry: chronic disease management, complex diagnostics, long-term follow-up

c. Align your application materials

Your ERAS experiences, letters, and personal statement should reflect your current specialty choice:

- Secure at least 2–3 letters from attendings in your new specialty

- Adjust your experiences descriptions to highlight skills relevant to the new field

- If you previously applied to another specialty, be ready to explain the transition confidently in interviews

4. Inconsistent Work or Clinical History

A patchwork of short-term positions can sometimes signal instability or difficulty maintaining roles. For many applicants—especially IMGs—this also reflects real constraints (visas, funding, limited opportunities).

How to Tackle:

a. Connect the dots into a purposeful narrative

In your personal statement or interviews:

- Explain why each position was short-term (e.g., observership limited to 3 months, contract-based research)

- Emphasize what you gained from each setting

- Show a trajectory toward increasing responsibility and stability

b. Emphasize reliability and professionalism

Ask letter writers from these roles to comment explicitly on:

- Your commitment and punctuality

- How you integrated into the team

- Your willingness to take on responsibility within scope

c. Show recent, continuous engagement

Recent, sustained activity (e.g., a one-year research position, a long-term clinical support role) helps balance earlier fragmentation.

5. Negative Evaluations, MSPE Comments, or Letters of Recommendation

Mediocre or negative evaluations can be among the most concerning red flags, especially when they involve:

- Professionalism

- Communication problems

- Team conflict

- Patient safety issues

How to Tackle:

a. Prevent additional problems going forward

If you’re still in training:

- Seek direct feedback early and often

- Ask specific questions: “What can I do differently to better support the team?”

- Demonstrate change across subsequent rotations (on-time notes, following up on tasks, responsiveness to pages)

b. Choose your letter writers strategically

Ask attendings who can genuinely advocate for you and have seen your growth:

- Prefer supervisors who can compare your performance favorably to peers

- Provide them with an updated CV and a summary of your red-flag context and how you’ve improved

- If appropriate, ask them to comment on prior concerns and how you addressed them

c. Be prepared to address issues directly in interviews

If you know there’s a clear negative comment (e.g., MSPE mentioning professionalism remediation), have a practiced, honest, and brief explanation:

- State the issue succinctly.

- Take appropriate responsibility.

- Describe specific steps you took to improve.

- Share evidence of better performance since then.

“In my third-year surgery rotation, I received feedback that I was occasionally late to rounds and slow to complete tasks. I took this seriously, met with my clerkship director, and implemented concrete changes—using earlier alarms, prioritizing tasks more effectively, and checking in regularly with my senior. On subsequent rotations, my evaluations consistently mentioned punctuality, reliability, and improved work efficiency.”

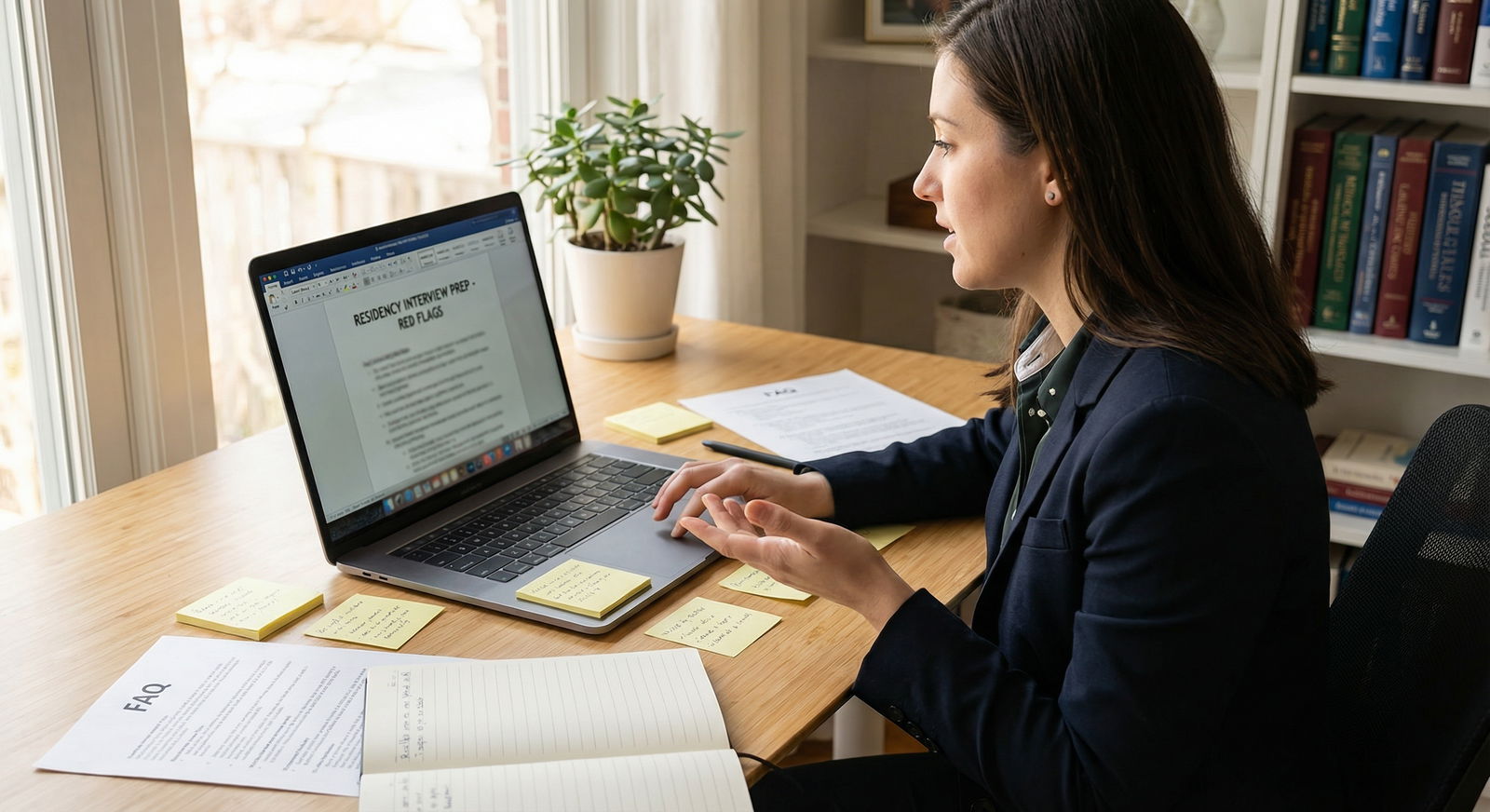

6. Incomplete, Late, or Disorganized Applications

Programs receive hundreds to thousands of Residency Applications; disorganized submissions suggest you may struggle with the logistics of residency itself.

How to Tackle (and prevent):

Start early with a detailed timeline.

Map deadlines for ERAS, letters, personal statement drafts, MSPE release, and supplemental applications.Use checklists and project management tools.

Spreadsheets, task apps, or simple paper planners can all work—choose what you’ll actually use.Have multiple reviewers.

Ask a mentor, advisor, or trusted peer to:- Check for omissions, typos, and inconsistencies

- Confirm that your red-flag explanations are clear and professional

Submit early in the season whenever possible.

Especially important if you have red flags—programs are more likely to take a chance earlier before interview slots fill.

If you have a history of missing deadlines (e.g., late coursework, incomplete prior applications), emphasize recent evidence of better organizational skills—such as timely research deliverables or leadership roles.

7. Withdrawals, Leaves, or Dismissals from a Prior Program

This is among the most serious categories of red flags but not insurmountable if managed correctly and honestly.

How to Tackle:

a. Be transparent and factual

You must disclose prior residency training and reasons for leaving truthfully. Failure to do so can jeopardize licensure later.

In your explanation (written and verbal):

- Briefly describe the circumstances: academic, performance-related, personal, or program-related

- Avoid disparaging individuals or programs

- Focus on your growth, insight, and current stability

b. Strengthen your application post-event

Programs will look particularly closely at what you did after the dismissal or withdrawal:

- Clinical work under supervision with strong evaluations

- Additional coursework or exam improvements

- Therapy or counseling if personal or mental health issues were involved

- Clear support from new supervisors stating you are ready for training

c. Get guidance from institutional leaders

Speak with:

- Your former program director (if possible)

- A dean or GME office

- A physician mentor experienced with remediation and re-entry

They can help you:

- Decide which programs/specialties are realistic

- Craft an appropriate explanation

- Identify colleagues willing to advocate for you

Crafting a Strong, Cohesive Narrative Despite Red Flags

Ultimately, programs are not just evaluating your past—they are assessing your future performance and potential.

Key Components of a Strong Application Narrative

Personal Statement with Purpose

- Mention major red flags briefly if they are central to your story.

- Focus on what you learned and how you changed.

- Link experiences to specific skills relevant to your chosen specialty.

- Avoid a tone of self-pity or defensiveness.

Experiences That Demonstrate Growth

- Highlight leadership, quality improvement, teaching, or research to show initiative.

- Emphasize roles that required reliability and teamwork.

- Write experience descriptions that show impact, not just duties.

Letters That Confirm Your Readiness

- Strong, specialty-specific letters are one of the most powerful antidotes to red flags.

- Target letter writers who:

- Worked with you recently

- Can compare you to peers

- Can specifically attest to areas previously questioned (professionalism, reliability, clinical judgment)

Interview Preparation Focused on Insight and Resilience

- Practice answering: “Tell me about a challenge or setback you’ve faced” and “Can you explain [red flag]?”

- Use the STAR method (Situation, Task, Action, Result) to structure answers.

- Keep explanations short, then pivot: “What I’d really like to highlight is how that experience changed the way I…”

Mentorship and Advising Support

- Engage early with:

- Specialty advisors

- Dean’s office or career services

- Alumni who matched with similar red flags

- They can help you decide:

- Which specialties and programs are realistic

- Whether to apply more broadly or include community programs

- If a transitional year or research year might help

- Engage early with:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Can residency application red flags be completely overcome?

Many can be significantly mitigated, especially when there is a clear pattern of improvement, honest explanation, and strong recent performance. Some issues (e.g., serious professionalism violations or repeated exam failures) will limit options, but even then, applicants often match into less competitive specialties or programs that value their growth and resilience. The key is realistic planning, mentorship, and a well-crafted Application Strategy.

2. Should I always mention red flags in my personal statement?

Not always. Mention red flags in your personal statement when:

- They are central to your story and growth,

- They would otherwise appear unexplained and concerning,

- You can connect them to meaningful changes in behavior or perspective.

If the issue is minor or adequately explained elsewhere (e.g., MSPE or ERAS comment), you may opt not to highlight it in the personal statement. When in doubt, ask a trusted advisor to review.

3. How do I know if a problem in my application is a true red flag or just a minor weakness?

In general, true red flags are:

- Failures (courses, clerkships, licensing exams)

- Leaves, withdrawals, or dismissals

- Professionalism or disciplinary issues

- Long, unexplained gaps in training

- Very late or incomplete applications

Single low grades, average scores, or a less research-heavy CV are usually weaknesses, not red flags. Program directors expect variation. Feedback from advisors, deans, or mentors is invaluable in distinguishing these.

4. What if I get asked directly in an interview about a painful or personal issue (e.g., mental health, family crisis) behind a red flag?

You are not obligated to disclose intimate details. You can:

- Acknowledge that a significant personal challenge occurred,

- Indicate, in general terms, how you addressed it (e.g., seeking appropriate support and treatment),

- Emphasize your current stability and readiness for residency.

Example:

“During that period, I was dealing with a significant personal health issue. I sought appropriate care, followed recommendations, and have been stable and fully functioning for [X] time. The experience taught me the importance of seeking help early and maintaining balance, which I now prioritize.”

5. Are there programs that are more open to applicants with red flags?

Yes. While no program advertises itself this way, community-based programs, smaller programs, and those with strong educational cultures often look for potential and growth rather than perfection. Networking—away rotations, research collaborations, direct contact with program leadership—and strong, honest advocacy from mentors can be especially effective for applicants with red flags.

Handled thoughtfully, red flags in Residency Applications do not have to define your future. By understanding how programs interpret these signals, taking ownership of your story, and demonstrating consistent growth, you can turn your application’s bumps and bruises into evidence of resilience—the kind of quality every residency program needs.