Recognizing the Signs of Burnout in Residency: Are You at Risk?

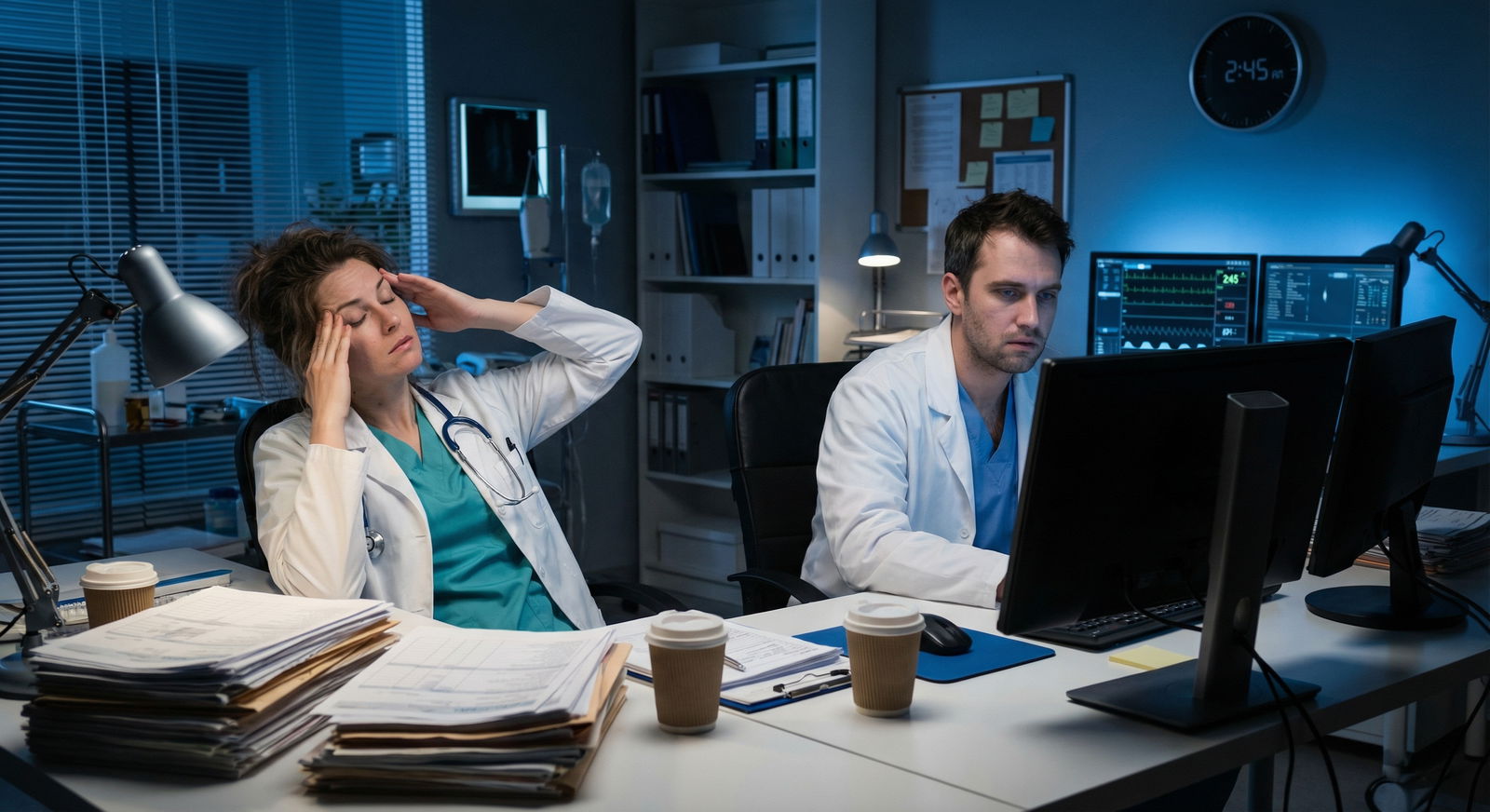

Burnout is no longer a distant, abstract concept in healthcare—it’s an everyday reality for many medical students, residents, and attending physicians. Residency, in particular, combines long hours, high expectations, emotional intensity, and steep learning curves. Under these conditions, burnout can develop gradually and silently until it profoundly affects your mental health, clinical performance, and personal life.

Understanding what burnout looks like in real time—not just as a textbook definition—is a powerful form of self-care and a critical step in protecting your wellness. This guide will help you:

- Understand what burnout is (and what it isn’t)

- Recognize physical, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral warning signs

- Identify personal and systemic risk factors in residency and healthcare

- Apply practical, realistic strategies to prevent and recover from burnout

- Know when and how to ask for help

This article is written with residency life in mind, but the principles apply to anyone working in healthcare.

What Is Burnout in Healthcare?

Burnout is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an occupational phenomenon resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is not classified as a mental disorder but is closely linked to mental health outcomes such as depression and anxiety.

Burnout has three core dimensions:

1. Emotional Exhaustion

You feel emotionally drained, depleted, and “used up” at the end (or beginning) of the day. For residents, this might look like:

- Dreading sign-out or morning rounds before your shift even starts

- Feeling like you have nothing left to give—to patients, colleagues, or family

- Crying unexpectedly or feeling numb when things go wrong

- Experiencing compassion fatigue when faced with suffering or bad outcomes

2. Depersonalization (Cynicism)

You begin to distance yourself psychologically from your work and patients. Common signs:

- Referring to patients as “the gallbladder in 10” instead of by name

- Making cynical remarks about “difficult” patients or families

- Feeling irritated or resentful when a patient asks questions

- Viewing patients as tasks or problems rather than human beings

Over time, this emotional distancing can erode your sense of purpose in medicine.

3. Reduced Personal Accomplishment

You feel ineffective, incompetent, or that your work doesn’t matter:

- Questioning whether you’re cut out for medicine

- Feeling that no matter how hard you work, you’re never “good enough”

- Minimizing your successes and magnifying your perceived failures

- Believing that your contributions don’t make a difference

In residency, where evaluation is constant and feedback can be inconsistent, this dimension can be especially potent.

Recognizing the Signs and Symptoms of Burnout

Burnout rarely appears overnight. It develops gradually, often masked by the culture of healthcare that normalizes exhaustion. Being able to identify the early signs in yourself and your peers allows for timely intervention and prevention.

1. Physical Signs of Burnout

Residency already challenges sleep and energy, but burnout amplifies these issues and adds new ones.

Chronic Fatigue:

- You wake up tired despite several hours of sleep.

- Days off don’t feel restorative.

- You feel physically heavy, slowed, or “running on fumes.”

Sleep Disturbances:

- Difficulty falling or staying asleep—racing thoughts about patients, notes, or evaluations.

- Frequent early waking with anxiety about the upcoming shift.

- Irregular sleep-wake cycles that never seem to stabilize, even on lighter rotations.

Frequent Illness and Somatic Complaints:

- Recurrent colds, flu-like symptoms, or infections.

- Persistent headaches, migraines, or muscle tension (neck, shoulders, back).

- Gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, diarrhea, constipation, stomach pain) not explained by other conditions.

Changes in Appetite and Energy:

- Skipping meals or overeating, especially high-sugar or high-caffeine foods.

- Reliance on coffee or energy drinks to “function.”

- Noticeable weight changes over a relatively short period.

While these symptoms can have multiple causes, when they cluster with emotional and cognitive changes, burnout should be considered.

2. Emotional Signs of Burnout

The emotional toll of residency is significant even in healthy conditions. Burnout amplifies negative emotional states and erodes your ability to cope.

Detachment, Cynicism, or Emotional Numbing:

- Feeling emotionally flat in situations that previously moved you.

- Using dark humor excessively to cope with difficult cases.

- Seeing patients as “just another admission” rather than individuals.

Irritability and Frustration:

- Snapping at colleagues, nurses, or family over minor issues.

- Feeling constantly “on edge” or easily overwhelmed.

- Interpreting neutral feedback as personal criticism.

Loss of Motivation and Joy:

- Struggling to recall why you went into medicine.

- Feeling dread instead of excitement about procedures or learning opportunities.

- Losing interest in activities and hobbies outside of medicine.

Hopelessness or Emotional Overload:

- Feeling that nothing will improve, that this pace is “forever.”

- Crying in call rooms, bathrooms, or in your car after shifts.

- Feeling guilty for not “handling it better.”

3. Cognitive Signs of Burnout

Burnout impacts how you think, process information, and make clinical decisions—critical for safe patient care.

Difficulty Concentrating:

- Reading the same paragraph of a note or guideline repeatedly without absorbing it.

- Struggling to follow sign-out or complex discussions during rounds.

- Feeling mentally “foggy” or slow.

Forgetfulness and Errors:

- Missing orders, tests, or follow-ups you would previously have caught.

- Making documentation errors or mis-clicks in the EMR.

- Needing to triple-check simple tasks you once did confidently.

Chronic Procrastination:

- Putting off notes, discharge summaries, or prep for cases until the last minute.

- Feeling paralyzed by your to-do list.

- Avoiding important tasks because they feel overwhelming.

4. Behavioral Signs of Burnout

These are often more visible to others and can be critical signals for colleagues and program leadership.

Social Withdrawal and Isolation:

- Skipping post-call breakfasts, resident gatherings, or simple check-ins.

- Declining invitations from friends or family because you feel “too exhausted.”

- Spending your free time mostly sleeping, scrolling, or zoning out.

Changes in Work Ethic and Performance:

- Noticeable decline in thoroughness or enthusiasm on rounds.

- Increased call-outs, tardiness, or difficulty completing tasks on time.

- Reduced engagement in teaching, conferences, or academic projects.

Unhealthy Coping Behaviors:

- Increased use of alcohol, sleep medications, or other substances to “shut off.”

- Stress eating, chain caffeine use, or other compulsive behaviors.

- Doom-scrolling or binge-watching excessively to avoid thinking about work.

If you recognize yourself in many of these categories, you may be experiencing burnout—or be on the path toward it.

Are You at Risk for Burnout in Residency?

Burnout is multifactorial. It is not a personal failure or a sign of weakness—it is often a understandable response to chronic, unrelenting stress in healthcare settings. Some risk factors are systemic, others personal.

1. Work Environment and System-Level Factors

Healthcare systems and residency structures can strongly influence burnout risk.

High Workload and Demands:

- Long hours, frequent call, and limited control over your schedule.

- High patient volumes, complex cases, and constant multitasking.

- Administrative burdens (documentation, prior authorizations) that feel misaligned with your training goals.

Resource Limitations:

- Inadequate staffing (nursing, ancillary support) leading to more work for residents.

- Limited access to equipment, consultants, or services that delays care and adds frustration.

- Poorly functioning EMR systems that increase clerical burden.

Organizational Culture:

- A culture that glorifies self-neglect, “pushing through,” and chronic overwork.

- Stigma around asking for help or using mental health services.

- Lack of transparent communication or responsiveness from leadership.

2. Personal Characteristics That Can Increase Risk

Certain traits common among medical trainees can paradoxically raise burnout vulnerability.

Perfectionism and High Self-Expectations:

- Feeling devastated by minor mistakes or constructive criticism.

- Difficulty accepting “good enough” when perfection isn’t possible.

- Constant internal pressure to be the “perfect resident.”

People-Pleasing and Over-Responsibility:

- Taking on extra shifts or tasks at the expense of your own wellness.

- Struggling to say “no” when you’re already exhausted.

- Feeling personally responsible for every outcome, even when systemic issues are involved.

Difficulty Setting Boundaries:

- Checking messages and notes long after your shift ends.

- Feeling guilty for taking days off or using vacation time.

- Allowing work to consume nearly all aspects of your identity.

3. Lack of Support and Social Isolation

Humans—and especially healthcare professionals—need connection and shared understanding.

Weak Support Systems at Work:

- Few trusted colleagues to debrief difficult cases with.

- Limited mentorship or role models who model healthy boundaries.

- Competitive, rather than collaborative, training environments.

Limited Support Outside of Work:

- Being geographically distant from friends and family.

- Difficulty maintaining relationships due to schedules and fatigue.

- Feeling like “no one outside medicine understands.”

4. Role Fit and Professional Misalignment

When your daily work feels disconnected from your values, burnout risk rises.

Role Ambiguity:

- Unclear expectations about your responsibilities or autonomy.

- Conflicting messages from different attendings or services.

- Uncertainty about how you’re really performing.

Misalignment with Values or Goals:

- Feeling pressured into a specialty, practice style, or career path that doesn’t fit.

- Ethical distress (e.g., resource limitations or systemic inequities) without space to process it.

- Lack of opportunities for the aspects of medicine you care about (teaching, research, advocacy).

Knowing your risk profile doesn’t doom you to burnout. It helps you identify where to focus your efforts for prevention and where to ask for help or systemic change.

Strategies for Burnout Prevention and Recovery

Burnout requires both individual-level and system-level solutions. While you may not be able to change your rotation schedule or EMR, there are strategies you can realistically implement—even in residency—to protect your wellness and mental health.

1. Foundational Self-Care Practices (That Actually Fit Residency)

Self-care in healthcare cannot just be “take a bubble bath” advice. Effective self-care is intentional, realistic, and sustainable.

A. Microbreaks and Reset Moments

- Take 30–60 second pauses between patients or tasks: one deep breath with a slow exhale, a shoulder roll, standing up and stretching.

- Use built-in moments (waiting for labs to load, elevator rides) to consciously relax your jaw, drop your shoulders, and breathe.

- Step outside for a minute or two of sunlight and fresh air when possible.

B. Exercise in Flexible Forms

- Short, 10–15 minute workouts can help more than waiting for a “perfect” workout:

- A brisk walk around the block post-call.

- Simple body-weight exercises (squats, push-ups, planks) at home.

- Aim for consistency over intensity—2–3 times per week is better than sporadic all-or-nothing bursts.

C. Sleep Hygiene—Even With Call

- Protect your post-call sleep as non-negotiable whenever possible.

- Use a sleep mask, earplugs, or white noise apps to maximize quality.

- Limit caffeine late in the day; try to taper before bed.

- On night float, maintain as consistent a schedule as possible, even on days off.

D. Supporting Nutrition Under Constraints

- Keep simple, high-protein, portable snacks on hand (nuts, yogurt, cheese sticks, protein bars).

- Pack at least one “real” meal when you can to avoid vending machine dinners.

- Hydrate—keep a refillable water bottle in your workroom or coat pocket.

2. Protecting Work–Life Boundaries

You cannot pour from an empty cup. Boundaries are not selfish; they are a professional necessity.

Define “off-duty” times:

- Commit to not checking work email or EMR outside of designated times, unless on call.

- Turn off non-urgent notifications on your phone when home.

Use Your Time Off Intentionally:

- Plan at least one meaningful, non-medical activity on days off (walk with a friend, hobby, meal out).

- Protect vacation time; avoid using it solely to catch up on documentation or research.

Communicate Boundaries Clearly and Respectfully:

- Practice phrases like, “I can help with that after I finish X critical task,” or “I’m at capacity right now—can we prioritize together?”

- When needed, involve chiefs or program leadership in workload discussions.

3. Building Connection and Seeking Support

Community is a powerful antidote to burnout.

Peer Support:

- Debrief challenging cases informally with trusted co-residents.

- Normalize conversations about burnout in resident groups—“How are you really doing?”

- Consider peer-led wellness initiatives (case debriefs, reflection rounds).

Mentorship:

- Seek out attendings or senior residents who model sustainable careers.

- Ask how they handled burnout risk during their training.

- Use mentorship meetings not just for research and career talk, but also for wellness strategies.

Professional Mental Health Resources:

- Use employee assistance programs (EAPs), resident wellness offices, or institution-provided counseling.

- If confidentiality is a concern, explore external therapists familiar with healthcare culture.

- Therapy is a proactive tool for mental health, not just a crisis measure.

4. Reassessing Your Role, Goals, and Expectations

Burnout can sometimes be a signal that part of your path needs realignment, not that you’re failing.

Identify Major Stressors You Can Influence:

- Keep a simple log for a week: what repeatedly drains you vs. what restores you?

- Discuss potential changes with your chief residents or program director (schedule adjustments, research load, committee roles).

Revisit Your “Why” in Medicine:

- Reflect on meaningful patient encounters and what drew you to this field.

- Keep a digital or physical “wins file”—thank-you notes, positive feedback, memorable moments.

Adjust Unrealistic Internal Standards:

- Aim for competence and growth, not perfection.

- Recognize that learning curves are steep in residency; mistakes, when constructively addressed, are part of training.

Explore Long-Term Fit:

- If ongoing misalignment persists, talk with trusted mentors about potential specialty shifts, fellowship options, or different practice settings.

5. When Burnout Is Severe: Taking It Seriously

Sometimes, burnout progresses to the point that you cannot safely “push through.”

Red flags include:

- Persistent thoughts of self-harm or that others would be “better off” without you

- Inability to perform basic work or self-care tasks

- Significant substance use escalation

- Severe, unrelenting anxiety, depression, or panic

In these situations:

- Reach out immediately to a mental health professional, crisis hotline, or trusted faculty member.

- Most programs and licensing boards are increasingly supportive of physicians seeking treatment—ask about confidential, non-punitive resources.

- A temporary leave or schedule adjustment, when medically indicated, is a sign of strength and responsibility, not failure.

Frequently Asked Questions About Burnout in Residency

1. What is the difference between normal residency stress and true burnout?

Residency stress is expected and often intermittent—busy weeks, challenging rotations, high-acuity patients. You may feel tired or pressured, but:

- You still have moments of satisfaction or joy.

- Rest days help you recover.

- The stress feels time-limited or rotation-specific.

Burnout is more persistent and pervasive:

- Emotional exhaustion feels constant.

- Cynicism and detachment spread beyond specific rotations.

- You question your value, competence, or your decision to pursue medicine.

- Symptoms persist despite sleep, time off, or rotation changes.

If your distress is enduring and affecting multiple areas of life and functioning, it’s time to consider burnout and seek support.

2. Can burnout affect patient care and my clinical performance?

Yes. Burnout is strongly linked in research to:

- Increased medical errors and near-misses

- Lower patient satisfaction

- Reduced empathy and patient-centered communication

- Higher rates of unprofessional behavior or conflict

This is one reason why addressing burnout is not just about personal wellness; it is a patient safety and quality-of-care issue. Seeking help is an ethical, professional action.

3. How can I talk to my program leadership or supervisor about burnout without being judged?

Prepare for the conversation with:

- Specific examples: “Over the past month, I’ve noticed increased difficulty concentrating and earlier fatigue during call.”

- Impact on work: “I’m concerned this may affect my performance and want to address it proactively.”

- Clear goals: “I’d like to explore options to support my wellness—whether that’s mentorship, schedule modification, or connecting with counseling resources.”

Most program directors now recognize burnout as a serious residency issue. Framing the conversation around patient care, professional development, and safety helps align your needs with program goals.

4. Is burnout reversible once it develops?

Yes. Burnout is highly responsive to targeted interventions, especially when addressed early. Recovery may include:

- Adjusting workload or schedule

- Engaging in therapy or counseling

- Improving sleep, exercise, and nutrition patterns

- Strengthening social support and mentorship

- Reconnecting with meaningful aspects of medicine

Many physicians who have experienced burnout go on to build sustainable, fulfilling careers—often with deeper self-awareness and clearer boundaries.

5. Can anyone in healthcare develop burnout, or are some specialties “immune”?

No specialty or role in healthcare is immune. Burnout has been documented across:

- Residents and fellows in all specialties

- Attending physicians

- Nurses, NPs, PAs, pharmacists, therapists, and other allied health professionals

- Non-clinical healthcare staff and administrators

Risk levels may vary by specialty, setting, and workload, but burnout can affect anyone. Universal prevention strategies and a culture that prioritizes wellness and mental health benefit the entire healthcare team.

Recognizing the signs of burnout is not an admission of failure—it’s an act of professionalism, self-respect, and patient advocacy. By understanding your risk factors, listening to your body and mind, and taking concrete steps toward self-care and support, you can build a career in medicine that is not only impactful, but sustainable and humane.

Your wellness matters as much as the wellness of the patients you serve.