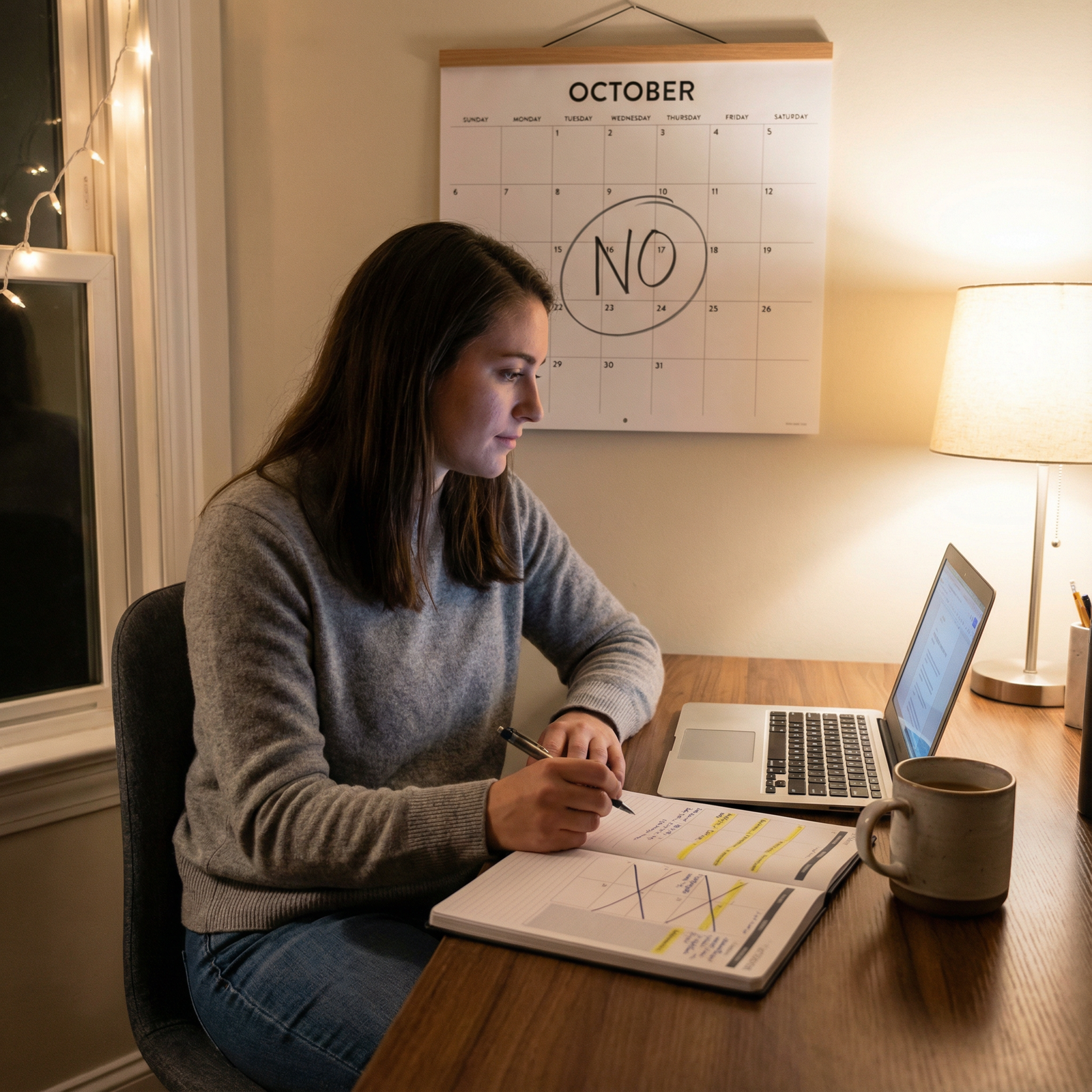

Introduction: Why Learning to Say “No” Is a Core Residency Skill

Residency is a high-stakes blend of long hours, intense clinical responsibility, constant learning, and the pressure to build a competitive CV. You’re expected to be a compassionate clinician, a diligent student, an emerging researcher, and, somehow, a functioning human with a personal life.

In this environment, your capacity to say “no” is as essential as your ability to interpret an EKG or manage sepsis. Protecting your time is not selfish; it is a cornerstone of safe patient care, sustainable professional growth, and long-term burnout prevention.

Yet most residents struggle with this:

- You don’t want to disappoint attendings or program leadership.

- You worry saying no might harm your reputation or evaluations.

- You fear missing out on opportunities that could help your future career.

This article reframes saying “no” as a skillful, professional behavior—one that supports your time management, wellbeing, and personal development. You’ll learn:

- Why overcommitting is so common and so dangerous in residency

- How to define and protect your priorities

- Concrete scripts and strategies to say “no” clearly and respectfully

- Ways to set boundaries with peers, attendings, and even yourself

- Real-world scenarios and how residents navigated them

- How mastering this art actually accelerates your professional trajectory

The Hidden Cost of Always Saying “Yes”

Overcommitment, Burnout, and the Myth of the “Perfect Resident”

Residency culture often celebrates the “yes” resident—the one who volunteers for every extra shift, joins every committee, signs onto each research project, and says yes to all teaching opportunities.

Underneath that, though, is a dangerous myth:

If you’re not overextended, you’re not committed enough.

Research on physicians and trainees consistently shows that:

- Chronic overwork and lack of control over one’s schedule are major drivers of burnout.

- Burnout is linked to increased medical errors, decreased empathy, and higher rates of depression and suicidal ideation.

- Once you’re burned out, it is much harder to engage meaningfully in learning, research, or leadership.

Consider a PGY-1 on inpatient medicine:

- Scheduled for six 12–14 hour days per week

- Already responsible for 10–15 patients daily

- Studying for in-training exams at night

On top of that, they are asked to:

- Join a quality improvement project

- Mentor medical students formally

- Cover an extra weekend for a co-resident

Each request, in isolation, seems reasonable. Collectively, they’re unsustainable. Saying yes to everything is not a sign of dedication—it’s often a pipeline to exhaustion and decreased performance.

Time as Your Most Valuable Residency Resource

During residency, time is your scarcest and most valuable resource. Money, academic opportunities, and connections can be rebuilt later. Time cannot.

Every “yes” is a “no” to something else:

- Saying yes to an extra research project may be saying no to adequate sleep.

- Saying yes to one more committee may be saying no to consistent board prep.

- Saying yes to frequent extra shifts may be saying no to relationships, hobbies, and basic self-care.

To protect your time, you need to ask yourself regularly:

- What are my top 3 priorities this month? (e.g., mastering inpatient medicine, preparing for Step 3/boards, maintaining my mental health)

- Does this new opportunity or request clearly support those priorities?

- What will I have to give up to take this on?

Skillful residents don’t say no to everything. They say a deliberate yes to what matters most and a respectful no to what does not.

Core Strategies for Saying “No” Without Burning Bridges

1. Get Clear on Your Priorities (Personal and Professional)

You cannot say no effectively if you’re not clear on what you’re protecting.

Define Your Current Season

Residency is not one uniform phase; it has “seasons”:

- Early intern year: surviving the learning curve, basic competence, time management

- Mid-residency: building a CV, research involvement, teaching roles

- Senior years: leadership, chief or fellowship prep, advanced clinical responsibility

Ask yourself:

- Professionally: What are my 1–2 primary goals for the next 3–6 months?

- Examples: “Pass my in-training exam,” “Submit one first-author manuscript,” “Prepare my fellowship application.”

- Personally: What is non-negotiable for my wellbeing?

- Examples: “At least one full day off per week when possible,” “Therapy twice a month,” “3 workouts per week,” “Time with my partner or kids each weekend.”

Write these out. When a request arrives, check it against this list:

“Does saying yes directly move me toward these goals—or does it dilute my limited time and energy?”

If it dilutes, that’s a strong signal you should say no—or at least “not now.”

Create a Priority Map

A practical tool:

- Must-Do: Required clinical work, mandatory educational activities, critical life responsibilities

- High-Value Optional: Select research, leadership, teaching that directly supports your goals

- Low-Value Optional: Committees, projects, social obligations that are nice, but expendable

Your “no” should live mainly in the Low-Value Optional category.

2. Use Respectful, Clear Language to Decline

Saying “no” is not about being evasive or apologetic. It’s about being:

- Honest about your bandwidth

- Respectful of the other person’s needs

- Direct and unambiguous

General Formula for a Professional “No”

You can structure many responses as:

- Appreciation

- Brief, honest rationale (without oversharing)

- Clear decline

- (Optional) Alternative or future openness

Example (research project invitation):

“Thank you so much for thinking of me for this project—it sounds like important work. Right now, I’m fully committed to my current research and my upcoming exam, so I wouldn’t be able to give this the attention it deserves. I’ll have more bandwidth in about six months; if a similar opportunity arises then, I’d be very interested.”

This communicates:

- Respect for the offer

- Professionalism in not overcommitting

- A boundary that is firm but courteous

Scripts for Common Residency Scenarios

Extra Shift Coverage

“I’ve looked at my schedule and I’m already at my safe limit for shifts this month, especially with my upcoming nights and exam studying. I won’t be able to pick up an extra shift, but I hope you’re able to find someone who has more bandwidth.”

Committee or Task Force Invitation

“I appreciate being included. At this time, I’m focusing my non-clinical time on board prep and one major QI project. I wouldn’t be able to participate consistently, so I’ll have to decline.”

“Can you just quickly…” from a colleague

“I’m in the middle of finishing notes and discharges that need to be done before sign-out, so I can’t take that on right now. Have you tried asking X or checked if it can wait until tomorrow?”

3. Set and Communicate Clear Boundaries

Boundaries are not walls; they are expectations about what you can realistically do without harming yourself or your work.

Boundary Types in Residency

- Time Boundaries: Protected studying time, sleep, therapy appointments, religious observances, family events where possible.

- Task Boundaries: Types or volumes of extra duties you will or will not take on.

- Communication Boundaries: How and when you are reachable outside of clinical duties.

Examples of Healthy, Explicit Boundaries

- “I’ve committed evenings after 8 pm to studying and sleep when I’m not on call, so I’m not able to attend meetings scheduled later than that.”

- “I can help with this QI project, but I can only commit one hour per week for the next two months.”

- “I can precept students during my outpatient days, but I can’t take on additional teaching responsibilities on weekends.”

Notice that these are specific, predictable, and communicated upfront. People can work around clear boundaries; they struggle with vague ones.

4. Practice Assertiveness: The Middle Ground Between Passive and Aggressive

Assertiveness means you:

- Respect your own needs and limitations

- Respect others’ needs and positions

- Communicate clearly and calmly

It is a learned skill—and practicing it early in your career supports lifelong professional growth.

Role-Play and Rehearsal

If you’re conflict-avoidant, saying “no” may feel intensely uncomfortable at first. Rehearse with:

- A co-resident you trust

- A mentor

- A partner or close friend

Practice saying:

- “I can’t take that on right now.”

- “I need to say no to this opportunity, but I appreciate being considered.”

- “That doesn’t fit with my current priorities, so I’ll have to decline.”

The more you say the words out loud, the easier it is to use them when it matters.

Using “I” Statements

When declining, use “I” language to own your decision:

- “I don’t have the capacity to do this well right now.”

- “I need to protect my time for X.”

- “I’m not able to commit to that this month.”

This is assertive and harder to argue with than:

- “You’re asking too much”

- “Nobody could do that”

- “That’s unrealistic”

5. Protecting Downtime as a Clinical Priority

Downtime in residency is not a luxury—it is a clinical safety measure. Sleep, rest, and time away are associated with:

- Reduced errors

- Better decision-making

- Improved emotional regulation and empathy

Create Non-Negotiable Recovery Time

Even with an unpredictable schedule, you can:

- Block one recurring “off” activity (e.g., Sunday dinner, weekly phone call with family, a class, therapy).

- Protect post-night-shift sleep as strictly as you would a patient’s treatment plan.

- Designate certain evenings as “no extra work” unless there is a true emergency.

Then, when requests come in:

“That’s my only protected recovery time this week, so I won’t be able to join. Thank you for the invite.”

Having these blocks pre-decided makes saying “no” easier—you’re defending an existing commitment, not inventing a reason.

6. Transparency and Collaboration With Your Team

Residents sometimes fear that being open about their limits will be seen as weakness. In reality, honest communication is a marker of maturity and professionalism.

How to Discuss Workload With Supervisors

Before you’re overwhelmed, schedule brief check-ins with your attending or program director:

“I want to make sure I’m balancing my clinical work with my other responsibilities and avoiding overcommitting. Here’s what I’m currently involved in—does this look sustainable from your perspective?”

When a new request comes from leadership:

“That opportunity sounds valuable. Here are the non-clinical responsibilities I have right now (research, teaching, committees). Do you think it makes sense for me to add this, or should I step back from something else first?”

This shifts the conversation from “I can’t handle it” to “Let’s make a strategic plan.”

Normalizing Asking for Help

If your workload becomes unsafe or unsustainable:

“I’m noticing that my current patient load plus extra duties is impacting my ability to care for patients the way I’d like to. Can we discuss redistributing some tasks or scaling back optional roles for now?”

This is not failing; it is safeguarding patients and yourself.

Real-World Case Examples: Saying “No” in Action

Case 1: The Overwhelmed Intern Who Rebuilt Her Schedule

Emily, a first-year intern, began residency like many high-achievers: she said yes to everything. Within the first three months she:

- Joined two research projects

- Signed up for a residency wellness committee

- Agreed to mentor two medical students

- Regularly covered extra shifts “to be a team player”

By month four, her symptoms included:

- Persistent fatigue despite sleep

- Irritability and detachment from patients

- Declining in-training exam scores

- Loss of interest in activities she previously enjoyed

With guidance from a senior resident, Emily:

- Listed all of her commitments on paper.

- Ranked them according to what directly advanced her core goals (clinical competence, exam success, and basic mental health).

- Met with her program director and research mentor to renegotiate roles.

She ended up:

- Staying on one research project and stepping away from the other.

- Pausing her wellness committee involvement for a year.

- Limiting extra shift coverage to no more than one per month.

Within two months, Emily noticed improved mood, better test performance, and more engaged patient interactions. Saying “no” allowed her to be fully present for the “yeses” that mattered.

Case 2: The Senior Resident Who Protected Exam Prep

Jake, a second-year resident with fellowship aspirations, was entering a critical period of board exam study. At the same time, co-residents invited him into a recurring weekly study group for a separate certification, plus a large QI project.

He recognized that:

- His exam prep was time-sensitive and central to his long-term goals.

- Adding weekly fixed commitments would fragment his time further.

Jake responded:

“I really appreciate you thinking of me, and I agree these are important activities. Right now, my priority is focused, protected time for board prep. I won’t be able to commit to a recurring weekly group or a large new QI project. If there’s a way I can contribute in a very limited, flexible capacity later—like reviewing data or helping with a write-up after my exam—I’d be open to that.”

Outcome:

- His colleagues respected his clarity and still valued his contribution later.

- He passed his boards comfortably, strengthening his fellowship application.

- He maintained relationships by being honest instead of overpromising and disappearing.

How Saying “No” Supports Long-Term Professional Growth

It can feel like declining opportunities will hurt your career, but in reality:

- Selective participation leads to deeper involvement and stronger output in a few key areas.

- Leaders value trainees who know their limits and deliver reliably on what they accept.

- Fellowship and job applications favor quality over quantity—sustained impact on projects, not a scattered list of brief, superficial roles.

Strategic “no’s” create space for:

- Focused, high-quality research or QI work

- Intentional mentorship relationships

- Consistent study habits and exam success

- Sustainable engagement in leadership roles later in residency

In other words, saying no is itself a form of professional development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Won’t saying “no” make me look lazy or uncommitted as a resident?

Not if you do it thoughtfully and respectfully. When you:

- Explain your current obligations honestly

- Emphasize your desire to deliver quality work, not just collect roles

- Continue to show up fully for the commitments you already have

…most attendings and program leadership will see you as self-aware and professional, not lazy. Inconsistent performance and unmet promises are far more damaging to your reputation than an occasional, well-reasoned “no.”

2. How can I start practicing saying “no” if I’m naturally a people-pleaser?

Start small and low-stakes:

- Practice declining minor social invitations when you need rest.

- Rehearse simple phrases aloud: “I can’t take that on right now,” “That doesn’t fit with my current priorities,” “I won’t be able to commit to that.”

- Role-play scenarios with co-residents or mentors.

Over time, you’ll discover that most people accept your no without drama—and the anxiety around it decreases. Think of it as building a new procedural skill: awkward at first, smoother with repetition.

3. What if saying “no” causes tension with peers or seniors?

Conflict is possible, especially in stressed teams. You can reduce friction by:

- Being timely and direct—don’t say “maybe” when you mean “no.”

- Explaining your rationale briefly, not defensively:

“I’m maxed out with my current patients and exam prep, so I can’t take that on safely.”

- Offering what you can do, if appropriate:

“I can’t join the full project, but I can review the survey draft once.”

If tension persists, seek support from a chief resident, mentor, or program director. Boundary-setting is a normal part of professional life, and you should not be punished for protecting your wellbeing and patient safety.

4. Can saying “no” actually advance my career in the long run?

Yes. Strategic “no’s” help you:

- Concentrate your efforts on a smaller number of meaningful, high-quality projects.

- Avoid burnout that can derail your training or lead to leaves of absence.

- Build a reputation as someone who delivers reliably on what they accept.

- Reserve energy for major milestones: boards, fellowship applications, capstone projects.

Program directors and future employers often prefer a resident who led one impactful QI project and published one solid paper—while remaining clinically strong and stable—over someone with a long list of briefly held, low-impact roles.

5. How do I cope with guilt after saying “no”?

Guilt is common, especially for those drawn to caregiving professions. To manage it:

- Remind yourself that you cannot care for others if you are depleted.

- Reframe your “no” as a yes to high-quality patient care, safety, and longevity in your career.

- Reflect on past times you overcommitted and how that affected your wellbeing and performance.

- Talk with peers or a therapist; many residents share this struggle, and normalizing it can help.

Over time, as you see the benefits—better focus, reduced burnout, improved learning—the guilt usually softens and is replaced by confidence in your boundaries.

Saying “no” as a resident is not a character flaw—it is a critical, learnable skill. When you align your yeses with your deepest priorities and use your noes to protect your time, energy, and mental health, you build a foundation for a sustainable, meaningful medical career.