Clinical volunteering will not rescue a weak academic record.

That sounds harsh, but protecting you from a preventable rejection is more important than protecting anyone’s feelings.

(See also: 10 Clinical Volunteering Mistakes That Quietly Undermine Your Apps for more details.)

Too many premeds and early medical students fall into the same trap: they pour hours into hospital volunteering, clinic work, and community health outreach, then act surprised when schools screen them out in the first 30 seconds because of GPA and MCAT. They confuse “important for growth” with “primary selection metric.” Admissions committees do not.

If you are quietly hoping that:

- 300+ hours of clinical volunteering

- year-round hospital shifts, or

- a “life-changing” global health trip

will compensate for a 3.1 science GPA or a 498 MCAT score, you are building your application on a dangerous illusion.

This is the mistake you must avoid.

The Harsh Reality: Clinical Experience Is Secondary, Not Foundational

You need to internalize one rule: academics are the filter; experiences are the differentiator.

Reverse that in your mind, and you will misallocate years of effort.

Admission committees at MD and DO schools use a predictable order:

Screen by numbers first

- Cumulative GPA

- Science GPA

- MCAT (or relevant standardized exam later in training)

Then evaluate experiences and attributes

- Clinical volunteering and shadowing

- Research

- Non-clinical service

- Leadership, work, life story

Volunteer hours only matter after you have passed the academic gate.

How screening actually works

At many schools, the first pass is done by:

- A software filter, or

- A staff member applying strict cutoffs

Common MD filters:

- cGPA below ~3.2–3.4 → auto-screened out

- sGPA below ~3.1–3.3 → significant concern

- MCAT below ~500–505 → risk at most MD programs (with exceptions)

DO schools may be more flexible, but they still have floors. No number of hours in the emergency department will override a file that never gets to human eyes.

If your application never makes it past the initial numerical filter, your incredible clinical story, letters, and compassion are invisible. That is not “unfair.” It is how schools manage tens of thousands of applications.

Mistake to avoid: Believing that being “passionate” and “experienced with patients” can substitute for being prepared for the academic rigor of medical school. Schools are not just selecting caring people; they are selecting people who will survive 4 brutal academic years plus 3–7 more in residency.

Why Clinical Volunteering Cannot Mask Academic Weakness

You might hear myths like:

- “Admissions committees love to see commitment to service.”

- “If you have a compelling story and lots of clinical hours, GPA won’t matter as much.”

- “Holistic review means they look past numbers.”

These statements have tiny grains of truth wrapped in dangerous misinterpretation.

Holistic review has boundaries

“Holistic” does not mean “ignoring red flags.” It means:

- Among applicants who meet basic academic standards, schools differentiate based on experiences, character, and fit.

- For applicants near the borderline, strong experiences and trends may help convince a committee to take a chance.

But it does not mean:

- 2.8 science GPA + 500 MCAT + 1000 volunteer hours → competitive

- Chronic poor academic performance “redeemed” by a beautiful personal statement about patient care

Clinical hours are not currency that buys back GPA points. They operate on a completely different axis.

Clinical work does not test what medical school demands

Medical school academics do not resemble:

- Walking patients to radiology

- Restocking supplies

- Doing intake vitals

- Translating simple instructions

- Observing procedures from a corner of the room

Those tasks matter ethically and professionally. They do not demonstrate:

- Your ability to master large volumes of complex content

- Your capacity for intense exam preparation

- Your consistency in high-stakes academic settings

Admissions committees know this. Volunteering shows commitment to service and understanding of the clinical environment, not cognitive readiness.

So when your grades and MCAT are weak, and you layer more clinical hours on top without fixing the root problem, you are adding breadth where you urgently need depth and competence.

Common Ways Students Misuse Clinical Volunteering

Let’s dissect the specific patterns that quietly sabotage applicants.

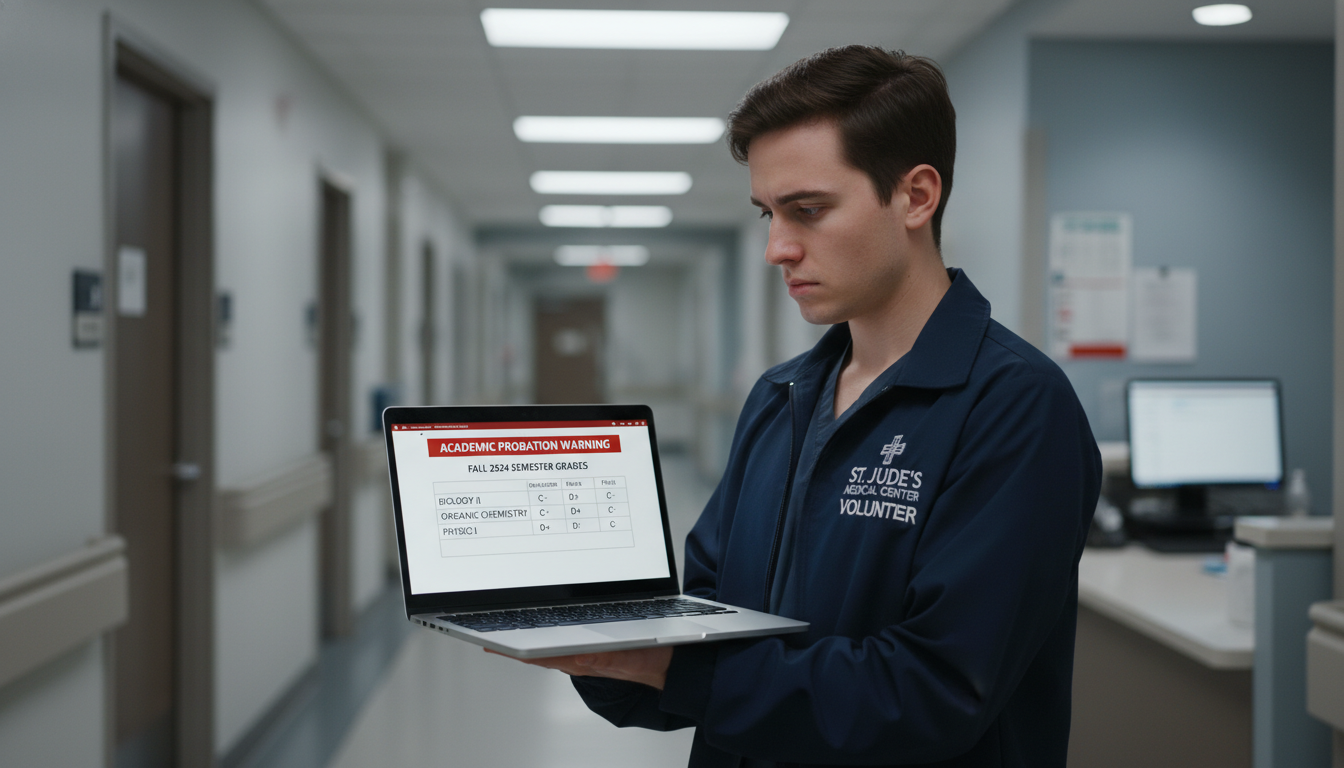

1. Volunteering as procrastination from academics

This might sound familiar:

- Organic chemistry is drowning you. So you say “At least my volunteering will show commitment,” and you keep your 8–10 hour hospital schedule instead of cutting back and finding a tutor.

- You feel guilty dropping shifts because the floor “depends on you,” yet your transcript is slowly collapsing.

Here is the harsh truth:

If your GPA suffers because of volunteering, you are not helping future patients. You are reducing the odds you will ever be in a position to treat them.

Correct approach:

- During difficult semesters, reduce clinical hours to a sustainable minimum (e.g., 2–3 hours per week or a brief pause).

- Use that time for:

- Office hours

- Structured study blocks

- Test-taking practice

- Sleep and recovery, so you are functional

You are not abandoning service. You are preserving your long-term capacity to serve.

2. Trying to “out-volunteer” poor grades

Another classic pattern:

- 3.0–3.2 GPA

- Limited upward trend

- MCAT still pending or borderline

- Yet you are chasing:

- 300–400+ clinical volunteering hours

- Several long-term hospital roles

- Extra weekend clinics

This is magical thinking: “If my file screams ‘service,’ surely someone will take a chance on me.”

Most schools are not looking for “the most hours.” They are looking for:

- Evidence you understand clinical realities

- Sustained involvement over time (not a 4-week binge)

- Reflection and growth

Beyond ~100–150 hours of genuine, engaged clinical exposure, extra time has diminishing returns, especially if:

- Your MCAT remains untested or mediocre

- Your GPA lacks an upward trajectory

- You have not taken (or retaken) key prerequisite courses

Your marginal hour is almost always better spent mastering biochemistry or practicing MCAT CARS than adding another repetitive shift answering call lights.

3. Using clinical work to “explain away” academics in essays

Some students try to spin a narrative like:

“My grades do not reflect my true potential, but my extensive clinical volunteering shows my dedication to patients and my resilience.”

Admissions committees see this framing constantly. They know the script. They are not impressed.

Appropriate use of clinical experience in essays:

- To demonstrate that you understand what medical practice entails

- To show you have observed the physician role realistically

- To illustrate communication skills, empathy, and teamwork

Inappropriate use:

- To distract from academic underperformance

- To suggest that your service proves you will handle rigorous medical science content

- To imply that emotional investment can substitute for mastery of foundational sciences

If you have academic weaknesses, you must show academic correction:

- Postbaccalaureate or SMP with strong performance

- Upward GPA trend with recent As in demanding science courses

- Improved standardized test performance

Anything else sounds like avoidance.

When Clinical Volunteering Actually Helps – And When It Does Not

Clinical experience is still essential. The mistake is thinking it is curative for academic problems. Let us be precise about what it does and does not do.

Clinical volunteering strengthens your application when:

Your academics are already competitive or improving

- GPA within or near typical accepted ranges

- MCAT at or above the 50th percentile for target schools

- Strong recent performance (even if you stumbled early)

Your hours are meaningful and stable

- 2–4 hours per week for 1+ years beats 100 hours in a single summer

- Roles where you actually interact with patients or the care team:

- ED volunteer with patient contact

- Medical assistant / scribe

- Hospice volunteer

- Free clinic intake or health navigator roles

You can articulate impact and reflection

- You can clearly describe:

- What you learned about the physician role

- How it shaped your motivation for medicine

- How it changed your communication style or perspective

- You can clearly describe:

In this situation, clinical volunteering is a powerful complement to a fundamentally solid academic profile.

Clinical volunteering does not rescue you when:

- Your science GPA is chronically low with no sustained recovery

- You repeated core courses multiple times without clear improvement

- Your MCAT is far below your target schools’ 10th percentile

- You have no clear plan for academic remediation

At that point, the hard truth:

You do not need more volunteering. You need evidence of academic resurrection.

How to Prioritize: A Rational Framework for Time Allocation

To avoid the “substitution” trap, you need a brutal but clarifying hierarchy.

Step 1: Stabilize and repair academics

Before expanding volunteering:

Audit your academic status:

- cGPA

- sGPA

- Trends by semester

- Performance in core prerequisites (Gen Chem, O-Chem, Physics, Bio, Biochem)

Identify whether you need:

- Better time management and study methods

- Fewer work/volunteer hours temporarily

- Tutoring or study groups

- Postbacc coursework or an SMP

Decide on a concrete repair plan:

- “Next 3 semesters: 12–14 credits max, intensive focus on upper-level biology, no more than 3–4 hours/week of volunteering.”

- “MCAT attempt delayed by 6 months while I rebuild foundation; I will not add new volunteer roles during this period.”

Step 2: Maintain baseline clinical exposure

You do not need zero clinical experience while fixing grades. You need right-sized exposure:

- 2–3 hours per week (or a short block after finals)

- Enough to confirm your interest in medicine and keep you engaged with patient care

- Flexible roles that allow you to scale back during exams

Think of this as:

- Academics: your primary job

- Clinical: a supporting role that must not threaten the main mission

Step 3: Expand clinical roles only after academic security

Once:

- Your GPA is trending upward

- You have solid recent semesters

- Your MCAT score is competitive or on track

Then you can:

- Add more shifts

- Take on more responsibility (e.g., scribe, MA, health coach)

- Pursue longitudinal roles at free clinics or primary care sites

Now, clinical volunteering becomes value-added rather than an escape hatch.

Special Cases Where Clinical Work and Academics Collide

Some students are not just “volunteers.” They are:

- Full-time CNAs

- Medical assistants

- EMTs

- Translators or community health workers

These roles are admirable. They can also destroy your academic prospects if handled poorly.

The working clinical student trap

Common scenario:

- 25–40 hours per week of clinical employment

- Full course load

- Chronic fatigue → mediocre grades

- Belief: “My work will show them I can handle medical environments and heavy responsibility.”

Reality:

- Many admissions committees respect employment

- But they cannot ignore:

- B/C averages in core science courses

- Repeated withdrawals

- MCAT scores dragged down by burnout

If you must work:

- Consider:

- Fewer credits per term

- A longer path to completion

- Taking heavier science loads during periods of reduced work

- Then clearly explain in your application:

- Your work obligations

- The adjustments you made to protect academic rigor

- How your performance improved once the load was reasonable

The mistake is trying to prove your resilience by overloading yourself into permanent academic mediocrity.

How Admissions Committees Interpret the “Service vs. Scholarship” Imbalance

You may think: “They will see how hard I worked for patients and understand why my grades slipped.”

Wrong interpretation.

When academic performance and clinical hours misalign, committees can read it in very different, often unflattering, ways:

- Poor judgment: You took on more than you could handle without protecting your core responsibilities.

- Lack of insight: You did not recognize that foundational science mastery is non-negotiable.

- Questionable readiness: If you could not manage undergrad + volunteering, how will you manage 60–80 hour med student weeks?

You want your application to say:

- “I know what medicine involves.”

- “I can handle intellectual rigor.”

- “I prioritize effectively under pressure.”

Using volunteering as a substitute for academics sends the opposite signals.

Red Flags You Are Making This Exact Mistake

If any of these statements feel uncomfortably accurate, pause now and recalibrate:

- “I do not have time to review lectures or do extra practice problems because of my volunteer shifts.”

- “My GPA is lower than I hoped, but I have amazing clinical experiences to talk about in interviews.”

- “I am applying this cycle despite my stats because I have over 400 hours of clinical volunteering.”

- “I keep saying I will fix my GPA next term, but I also keep adding new roles to my resume.”

Concrete warning signs:

- Two or more science courses below B- while maintaining >5–8 hours per week of clinical work

- No clear upward GPA trend in your last 3–4 semesters

- Planning an application with:

- cGPA < 3.3

- sGPA < 3.2

- Unproven or low MCAT

- But large, impressive-sounding clinical and service hours

If that is you, the problem is not your commitment. The problem is your strategy.

Protect Yourself: A Safer Strategy Moving Forward

To avoid wasting years chasing a fantasy, anchor your planning to these principles:

Academics are the gatekeeper.

Do not let anything—volunteering, work, leadership—consistently undermine course performance and test prep.Clinical exposure is essential but dose-dependent.

You need:- Enough to confirm career fit and inform your essays

- Not so much that it derails your academic trajectory

You fix academic weaknesses with academics, not with stories.

- Postbacc courses

- SMP programs

- Retakes with strong performance

- Improved MCAT after deliberate preparation

Every hour has an opportunity cost.

When your GPA is marginal:- One more ED shift might cost you one more B- in biochemistry

- That trade hurts far more than the extra 4 hours help

Medical schools are filled with people who balanced both. They are not filled with people who chose service instead of scholarship and hoped admissions would “understand.”

Your compassion matters. Just do not let it be the reason you never make it to the white coat.

FAQs

1. If my GPA is low, how many clinical hours do I need to “make up for it”?

You cannot “make up for” low GPA with clinical hours. They solve different problems. For a low GPA, you need:

- A strong upward trend

- Postbacc or SMP grades that are mostly As in rigorous sciences

- A solid MCAT relative to your target schools

Clinical hours should be targeted to demonstrate understanding of medicine, not to compensate for numbers. About 100–150 well-engaged hours are usually sufficient for that purpose. More hours help only after your academics are under control.

2. Can outstanding clinical volunteering help me if I am just below a school’s average stats?

Yes, but only at the margins. If your stats are:

- Slightly below the average but still near or above the 10th percentile for a school,

- And you have a clear upward trend academically,

Then strong, reflective, long-term clinical involvement can make you more compelling compared with similar applicants. It might push a borderline file into the interview pile. It still will not rescue you from being far below a school’s minimum thresholds.

3. Should I stop all volunteering if I am struggling in my classes?

Not usually. A complete stop can backfire if it leaves you disconnected from medicine and unable to speak credibly about clinical realities. Instead:

- Scale down to the smallest sustainable commitment, like 2–3 hours per week or intermittent blocks during academic breaks.

- Inform your coordinator that you are temporarily reducing hours to focus on academics.

Your goal is preservation, not elimination. Protect your grades without severing your link to clinical exposure.

4. How do I explain past over-commitment to clinical volunteering in my application?

You must show that you learned and corrected your approach. For example:

- Briefly acknowledge that earlier in college you overextended with clinical and work commitments.

- Emphasize how this affected your performance and what you changed:

- Reduced hours

- Sought academic support

- Improved your study strategies

- Point to concrete evidence of improvement:

- Strong recent semesters

- Better MCAT performance

- More balanced schedule

The key is to demonstrate growth in judgment. You are not excusing poor performance with volunteering; you are showing that you recognized the mistake and fixed it.

Key points:

- Clinical volunteering cannot substitute for strong academic performance; it only matters after you clear numerical screens.

- Do not let volunteering, no matter how meaningful, consistently undermine grades or MCAT prep.

- Repair academic weaknesses with academic solutions, and use clinical experience as a focused complement—not as a bandage for your transcript.