Most students are unprepared for how much inpatient oncology volunteering feels like real clinical work—especially the grief, emotional exhaustion, and constant pressure to "be there" for patients.

Let me be explicit: this is not just “getting hours” for your application. Inpatient oncology will confront you with dying patients, burned-out staff, families in crisis, and your own limits. If you do it thoughtfully, though, it can also be one of the most professionally shaping experiences you have before or during medical school.

You want to help. You also want to protect your own mental health and avoid crossing lines you do not yet fully understand. That tension—between empathy and boundaries, between presence and overinvolvement—is the core skill set of inpatient oncology volunteering.

(See also: Clinical Volunteering in Palliative Care: Communication Skills You’ll Gain for more on emotional support strategies.)

Let me break that down specifically.

1. What Inpatient Oncology Volunteering Actually Looks Like

Forget the brochure language. The real day-to-day is more concrete and far more emotionally loaded.

Typical inpatient oncology volunteer settings:

- Academic cancer centers (e.g., MD Anderson, Dana-Farber, Memorial Sloan Kettering)

- Oncology floors of large teaching hospitals

- Bone marrow transplant units

- Pediatric oncology inpatient units

Common responsibilities (depending on institution and your level):

- Patient support

- Sitting with patients who are alone, especially at night or after bad news

- Talking, reading, playing games, watching TV with them

- Comfort rounding (offering blankets, water, books, art supplies)

- Family support

- Escorting family members to waiting areas

- Getting coffee or water for caregivers during long chemo infusions

- Orienting new visitors to the unit (restrooms, cafeteria, quiet places)

- Staff support

- Stocking supplies, putting together chemo kits or comfort carts

- Running small errands to reduce nurse and tech workload

- Program-based support

- Art/music activities, journaling sessions, story-recording projects

- End-of-life legacy building (memory boxes, recorded messages)

Notice what is missing: you are not doing medical tasks. No vitals, no medication handling, no clinical decision-making. Your domain is presence, logistics, and emotional support within strict boundaries.

The emotional load is not in the tasks; it is in the context: recurrent hospitalizations, chemo complications, conversations about prognosis, patients who will not leave the hospital alive. You are stepping into the middle of those stories.

2. Understanding the Emotional Landscape: Grief, Ambiguous Loss, and Moral Distress

Volunteering in inpatient oncology is not just “sad”. It produces specific emotional patterns that are predictable—and manageable—if you understand what is happening.

2.1 Types of grief you will encounter

Anticipatory grief

Family members and sometimes patients grieving before death occurs. You might see:- Spouses sitting quietly, staring at monitors

- Parents asking “How much time?” repeatedly to different staff

- Patients talking about “when I am gone” long before hospice is official

Acute grief after death or bad news

You may be present right after:- A code that does not succeed

- A scan that shows major progression

- A decision to stop curative therapy and move to comfort care

Disenfranchised grief (yours)

Your grief is real, but:- You are “just the volunteer”

- You do not go to the funeral

- Staff may change the subject quickly and move to the next admission

Feeling like your sadness is not fully legitimate is common.

Cumulative/compound grief

You do not just grieve one patient. You carry small pieces of many:- The young parent with metastatic disease

- The teenager transplant patient who never engrafted

- The older patient who reminded you of a grandparent

Over months, this accumulates unless you learn intentional processing.

2.2 Ambiguous loss and unresolved endings

In inpatient oncology you often do not get closure:

- You come back after a week and the room is empty.

- The patient is “discharged,” but nobody says whether it was to rehab, home, or hospice.

- You grow close to a long-term inpatient; they disappear from the census overnight.

This is ambiguous loss—a loss without clear markers, funerals, or goodbye rituals. Many volunteers underestimate how disorienting this feels over time.

A practical strategy: keep a simple, de-identified reflection log (no names, no room numbers, just initials or descriptors and your feelings). Write down:

- “Middle-aged woman on BMT unit, loved crosswords, room empty this week. I feel…” This is not for applications; it is to help your brain register and process endings.

2.3 Moral distress for volunteers

Moral distress is the discomfort you feel when:

- You perceive that the care plan may be prolonging suffering, but you have zero authority.

- You hear a patient say “I do not want more chemo” and then see them scheduled for another cycle.

- A family appears in denial while the patient is clearly dying.

Volunteers sit at the bedside and hear raw, unfiltered comments from patients. You then watch staff execute complex, ethically loaded treatment plans without having full context. That mismatch breeds distress.

Key point: It is not your job to resolve ethical questions.

Your job is:

- To listen without promising things you cannot control.

- To bring concerns to the nurse or volunteer coordinator when something feels unsafe or clearly out of line.

- To accept that many decisions involve medical, prognostic, and family dynamics you cannot see.

3. Burnout and Compassion Fatigue: How They Show Up In Volunteers

You will not be immune to burnout just because you are “only” a volunteer. In high-intensity units, volunteers can burn out faster because they lack formal training and structured debriefing.

3.1 Recognizing early signs

Watch for these patterns over weeks—not just after one rough shift:

Emotional signs

- Numbness or “flatness” with patients

- Irritability with minor unit issues

- Dread the night before your shift

- Feeling guilty when you do not feel sad

Cognitive signs

- Persistent thoughts about specific patients during class or at home

- Difficulty concentrating after tough cases

- Thinking in all-or-nothing terms: “If I cannot really change outcomes, what is the point?”

Behavioral signs

- Frequently canceling shifts or shortening them

- Staying extra long “because they need me” (often a red flag for boundary problems)

- Increasing emotional distance: avoiding certain rooms because they are “too intense”

If several of these cluster for 3–4 weeks, you are not “just tired.” You are drifting into burnout or compassion fatigue.

3.2 Why premeds and medical students are at particular risk

There are specific vulnerability factors in your stage:

Performance pressure

You might think: “I need strong letters. I cannot admit this is too much.”Identity fusion with medicine

The role of “future doctor” becomes central to your self-worth. Suffering patients feel like a test of whether you are cut out for this.Limited coping skills for death

Many premeds have never seen a death up close. In oncology you may see multiple in one month.Lack of peer understanding

Your classmates studying MCAT or anatomy may not relate when you say, “I ate lunch after sitting with a dying adolescent for 2 hours this morning.”

Burnout is not a moral failure. It is a predictable occupational hazard in high-acuity environments. Serious clinicians treat it like bloodborne pathogens: identify, mitigate, and create structural protections.

4. Boundaries: The Single Most Underrated Skill in Oncology Volunteering

If I had to choose one non-clinical competency that distinguishes sustainable oncology volunteers from those who flame out, it would be boundary setting. Not “walls.” Boundaries.

4.1 Emotional boundaries: what they look like in practice

Boundaries are not about caring less. They are about caring within a realistic scope.

Examples of healthy emotional boundaries:

You can sit with a crying patient, offer tissues, listen attentively, but you do not promise:

- “I will be here every day.”

- “I will stay with you as long as you need tonight.”

- “I will talk to the doctors and fix this.”

You acknowledge your emotional reactions privately:

- “That conversation about leaving kids behind hit me hard,” but you do not unload those feelings on the patient or family.

You remember:

Their crisis is not your crisis, even if you are deeply moved by it.

Practical behaviors that reinforce emotional boundaries:

Use the volunteer role title intentionally:

“As a volunteer, I am here to sit with you and keep you company. I cannot answer medical questions, but I can help you get your nurse.”Time-box your emotional exposure:

If a room is consistently very heavy for you, ask the coordinator for a rotation that includes some lighter tasks (supply restocking, comfort cart) in between.

4.2 Time and availability boundaries

Your time is finite. Oncology units often feel like bottomless wells of need.

You must define:

- Maximum shift length you can handle emotionally (e.g., 3 vs 4 hours)

- Frequency per week that is sustainable with your academic load

- Non-negotiable no-volunteering times (e.g., week before major exams)

Red flags you are violating time boundaries:

- Staying 1–2 hours past your scheduled end “because this family really needs me”

- Agreeing to extra shifts every time someone cancels

- Feeling resentment toward the unit or patients for “taking” your time

A professional approach:

You end on time, but with structure:

“I need to go in five minutes, but I can ask the nurse if a chaplain, social worker, or another volunteer is available later today.”You say “no” to extra shifts with a neutral rationale:

“I am at my limit for this month with classes. I can pick up more next semester.”

4.3 Relational boundaries: self-disclosure and attachment

Patients often ask personal questions or invite you into their lives.

You must be clear on three zones of information:

Always appropriate (with discretion)

- First name, role: “I am Alex, a volunteer.”

- General educational status: “I am a premed / medical student.”

- Very broad hobbies: “I like running and reading.”

Usually inappropriate

- Social media handles

- Phone numbers or personal email

- Detailed romantic or family issues

- Specific political or religious opinions tied to prognosis (“I believe you’ll be healed if…”)

Situational and delicate

- Shared illness history of a family member

- Shared faith background

- Personal experiences with death

Ask yourself:

- “Am I sharing this to help the patient, or to relieve my own discomfort / gain closeness?”

- “Would I be comfortable with the attending physician hearing exactly what I said?”

4.4 Post-discharge or post-death contact

Generally:

- Do not initiate or accept ongoing contact (texts, social media friendships) with patients or families.

- Do not attend funerals unless your institution’s policy explicitly allows it and you discuss it with your coordinator.

This feels harsh to many volunteers, especially when a deep connection existed. The rationale is:

- Power dynamics: even as a student, you represent the institution.

- Professional identity: physicians cannot maintain close ongoing personal relationships with former patients.

- Emotional protection: repeated goodbyes and grieving at a personal level accelerate burnout.

If a family offers an invitation or asks for your contact:

- “I have really valued our conversations. Hospital policy and my role as a volunteer mean I cannot stay in touch after you leave, but I will be thinking of you.”

5. Concrete Coping Strategies During and After Shifts

Abstract advice does not hold up at 2 a.m. when you just sat with someone who knows they are dying. You need tactics.

5.1 During the shift: in-the-moment tools

Grounding while in the room

- Box breathing: inhale 4 seconds, hold 4, exhale 4, hold 4 (repeat privately).

- Physical anchor: press your feet into the floor, notice the chair supporting you.

- Micro-phrases in your head:

“I am here. I am listening. I do not have to fix this.”

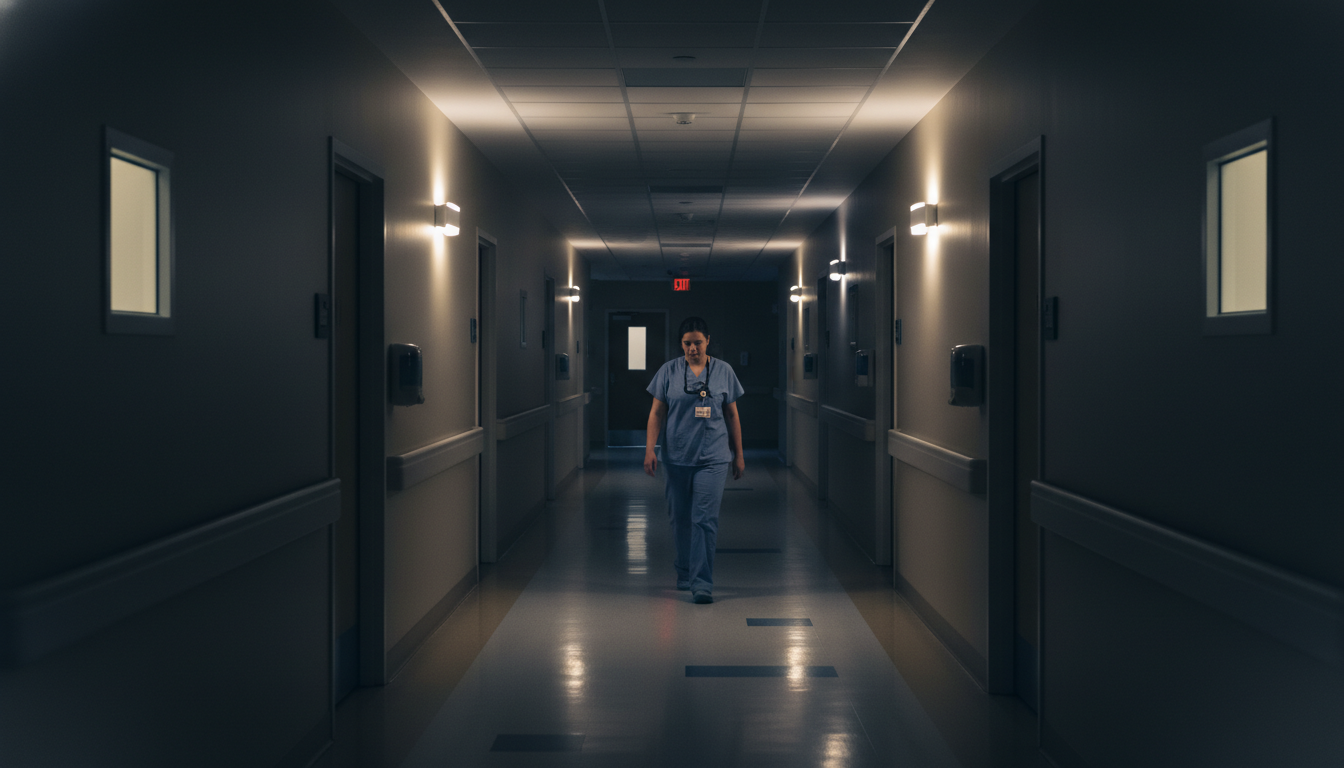

Stepping out strategically You are allowed to say:

- “I am going to step out to get you some water and let your nurse know how you are feeling. I will be back in a few minutes.” Use that 2–3 minutes to:

- Take 5 slow breaths in the hallway.

- Grab water and recenter before re-entering.

Using the team If a conversation becomes overwhelming or crosses into therapy, spirituality, or complex distress:

- Notify the nurse: “Room 412 expressed a lot of sadness and talked about not wanting to be here anymore. Could social work or chaplain see them today?” You are a sensor, not a one-person intervention team.

5.2 Immediately after the shift

Have a consistent post-shift routine. The exact components matter less than the consistency.

Possible structure (30–45 minutes):

Physical decompression

- Walk outside, even just around the block.

- Change out of volunteer attire as soon as possible (signal to your brain that the role is off).

Brief written reflection (5–10 minutes)

- One patient interaction that stuck with you.

- One feeling you noticed (e.g., helplessness, sadness, anger).

- One thing you did that aligned with your values.

Concrete transition ritual

- Music on the way home that is unrelated to medicine.

- A specific snack or tea you only have post-shift.

- If you commute by public transit, deliberately read or listen to something non-medical.

5.3 Longer-term maintenance

Scheduled check-ins with yourself

- Every 4–6 weeks, ask:

- “Is this still sustainable?”

- “Am I learning and showing up in the way I want?”

- “Has my baseline mood changed outside the hospital?”

- Every 4–6 weeks, ask:

Professional support when needed

- University counseling is not only for crises; many students use it to process repeated exposure to death and suffering.

- Some cancer centers have volunteer support groups or debrief sessions. Use them.

Adjusting your role

- It is acceptable to:

- Move from inpatient oncology to a lighter unit for a semester.

- Decrease hours temporarily.

- Shift to more task-based volunteering (e.g., outpatient clinic check-in) if your emotional bandwidth is low.

- It is acceptable to:

Pivoting does not mean you cannot become an oncologist. Many superb oncologists had periods during training when they needed distance.

6. Professionalism and Scope: What You Must Not Do

To be blunt: some premeds and early medical students get themselves into trouble by overreaching in oncology units.

6.1 Never cross into the clinical lane

You must not:

- Interpret scan results, labs, or prognosis.

- Comment on whether treatment is “working” or “worth it.”

- Disagree with the medical plan in front of the patient or family.

If asked directly:

- “Are my labs bad?” → “I do not have the training to interpret labs. Your nurse or doctor can explain them.”

- “Do you think this chemo will cure me?” → “Those kinds of questions are really important for your oncology team. I can help you write them down to ask them.”

6.2 Avoid back-channel communication

Situations to avoid:

- Patients or families asking you to carry messages to the doctor that they have not told staff.

- Asking clinicians for “inside information” to bring back to the patient.

- Sharing your personal theories about why decisions were made.

Proper channel:

- Encourage direct communication:

- “It sounds like you have important questions. Do you want me to help you ask the nurse to page the doctor or social worker?”

- If someone discloses unsafe situations (self-harm, abuse, etc.), you must notify staff immediately, even if they ask you not to.

6.3 Protecting confidentiality beyond HIPAA

You already know not to post identifiable patient info. But subtle leaks matter too.

Unsafe behaviors:

- Discussing specific patient stories with friends or classmates in public spaces.

- Sharing “funny” or “unusual” oncology cases in group chats, even without names.

- Using vivid, identifying details in application essays (age, diagnosis, family details, hospital name).

Safe alternative:

- Change details enough that the patient is not recognizable, and focus on your internal process:

- “I sat with a patient receiving life-prolonging but non-curative treatment and struggled with my sense of helplessness.”

7. Using This Experience Thoughtfully in Premed and Medical Training

You are not doing this solely for admissions, but it will shape your narrative.

7.1 For premeds: framing on applications and interviews

Admissions committees respond to specific, reflective experiences, not generic oncology sadness.

Strong ways to frame:

Skills:

- “I learned to be present with suffering without overpromising or overstepping my role.”

- “I developed early recognition of my own emotional limits and built routines to sustain myself.”

Concrete examples:

- Describe one conversation where you had to redirect a patient’s medical question.

- Describe a time you recognized your own need to step out, then returned grounded.

Weak framing:

- “It taught me to care about people” (too vague).

- “It showed me that life is short and we should follow our dreams” (more about you than about patients).

7.2 For early medical students: integration with training

If you continue or start inpatient oncology volunteering during pre-clinicals:

Treat it as early clinical exposure to:

- Serious illness conversations

- Interprofessional dynamics

- End-of-life care

Watch staff closely:

- How does a seasoned oncology nurse set boundaries kindly?

- How do attendings respond when families ask for “more chemo” despite poor prognosis?

- How do residents handle visible distress after a bad code?

Then, link what you see to coursework:

- Ethics → futile care, autonomy vs beneficence

- Communication skills → delivering bad news, listening to emotion

- Professionalism → role clarity, humility in the face of uncertainty

These observations will serve you far more than another hour of Anki.

FAQ (Exactly 4 Questions)

1. How long should I volunteer on an inpatient oncology unit to “get enough” experience without burning out?

There is no universal number, but a common sweet spot for premeds is 2–4 hours per week for 6–12 months. That duration allows you to see different disease trajectories, discharges, deaths, family dynamics, and your own reactions across multiple cycles, without overwhelming your schedule. If you find yourself emotionally overloaded, shorten shifts (e.g., 2 instead of 4 hours) before deciding to quit entirely. The moment you notice persistent dread before every shift for more than a month, reassess with your coordinator.

2. Is it normal to cry after a shift—or even in a patient’s room?

Crying after a shift is very common and can be a healthy release. Many volunteers cry in their car, on the bus home, or once they are in a private space. Crying in a patient’s room is more complicated. Brief, quiet tears that you acknowledge (“I am feeling this with you”) can be acceptable, but if your emotion becomes the focus of the interaction, it shifts the burden to the patient or family to comfort you. If you feel tears rising strongly, use a brief exit: “I am going to step out for a moment and get you some water,” then regroup and, if necessary, ask staff for support.

3. How do I know when it is time to step away from oncology volunteering altogether?

Key indicators: your baseline mood outside the hospital is significantly lower for several weeks; you feel numb or cynical toward new admissions; you are using avoidance (skipping shifts, procrastinating on emails) as your main coping strategy; or your academic functioning is clearly impaired. If you recognize these, speak with your volunteer coordinator and, ideally, a counselor. Stepping away, even permanently, does not mean you are unfit for medicine or oncology. It means you are taking your own mental health as seriously as you would want your patients to.

4. Can inpatient oncology volunteering “count” as clinical experience for medical school applications, even if I am not doing any hands-on medical tasks?

Yes. Admissions committees generally consider inpatient oncology volunteering direct clinical exposure if you are consistently interacting with patients and families in a healthcare setting, observing clinical teams, and participating in the rhythm of inpatient care. You do not need to perform procedures for it to be valid clinical experience. When describing it, emphasize patient contact, exposure to serious illness and end-of-life care, your understanding of team roles, and the way you learned to operate within boundaries. That framing makes the clinical value clear, even in a non-procedural role.

Key points:

- Inpatient oncology volunteering exposes you to real grief, ambiguous loss, and moral distress long before you have MD after your name; you must learn to recognize those experiences explicitly.

- Sustainable involvement depends on firm emotional, time, and relational boundaries, plus concrete post-shift coping routines and willingness to adjust your role when needed.

- If you approach this work thoughtfully, it will shape not only your application narrative but your professional identity—teaching you how to sit with suffering without trying to control it, which is central to the practice of medicine.