outreach with addiction medicine team Medical student engaging in [harm reduction](https://residencyadvisor.com/resources/clinical-volunteering/clinical-volunteeri](https://cdn.residencyadvisor.com/images/articles_v3/v3_CLINICAL_VOLUNTEERING_clinical_volunteering_in_addiction_medicine_harm_r-step1-medical-student-engaging-in-harm-reducti-2989.png)

Most premeds and early medical students get addiction medicine wrong: they think it is either glamorous “intervention” work or emotionally crushing detox shifts. It is neither. The real entry point is harm reduction.

If you want meaningful, clinically relevant volunteering in addiction medicine before residency, you do it through structured harm reduction work and clearly defined student roles—not by trying to “save” people or practicing outside your lane.

Let me break this down specifically.

Why Addiction Medicine and Harm Reduction Belong in Your Clinical Volunteering

Clinical volunteering in addiction medicine does several things at once:

- Exposes you to complex, high-stakes clinical decision-making (overdose, withdrawal, comorbidities)

- Forces you to confront bias and stigma head‑on

- Builds concrete skills that transfer to any specialty: motivational interviewing, trauma‑informed care, interprofessional teamwork

Harm reduction is the most realistic and ethical way for premeds and early medical students to plug into this field. You do not need prescribing power to:

- Educate about overdose recognition and response

- Distribute naloxone under a standing order

- Offer safer‑use counseling under supervision

- Connect patients to treatment, housing, or social services

- Help collect and interpret program data that shapes policy

Done right, this volunteering is not “shadowing plus sympathy.” It is structured, clinically adjacent work with outcomes you can actually measure: reversals, referrals, retention in care.

Core Harm Reduction Principles You Must Actually Understand

Before any clinical volunteering in addiction medicine, you should be able to articulate harm reduction in concrete, clinically grounded terms. Not as a slogan.

At minimum, internalize these pillars:

Any Positive Change

Harm reduction does not demand abstinence as the entry ticket. A patient who moves from injecting alone to using with someone who has naloxone has made a clinically meaningful change with survival impact.Non‑judgmental, non‑coercive services

You do not withhold care if a person continues using. You do not tie access to syringes or naloxone to a promise to “cut back.”Drug use exists on a continuum of risk

Your role is not to sort “good” vs “bad” behavior. Your role is to identify:- Higher overdose risk patterns (using alone, mixing sedatives, recent release from jail)

- Higher infectious risk patterns (shared syringes, reusing equipment, lack of sterile water) and then reduce those risks one step at a time.

Respect for autonomy and lived expertise

People who use drugs are not passive recipients of your benevolence. They are experts in what they have tried, what has failed, and what matters to them.Public health framing

Every naloxone kit, every sterile syringe, every HIV/HCV test is not just an individual intervention; it is a population‑level one. This is very different than the “I cured their addiction” fantasy new volunteers sometimes bring.

If you cannot explain why distributing sterile syringes lowers HIV incidence without increasing drug use rates (the data is extremely clear), you are not yet ready for front‑line harm reduction conversations.

Types of Clinical Volunteering Settings in Addiction Medicine

Not all “addiction volunteering” looks the same. The setting dictates both what you will see and what you are allowed to do.

1. Hospital‑Based Addiction Consult Services

Found at larger academic centers (e.g., Boston Medical Center, UCSF, University of Washington).

What these teams do:

- See inpatients with substance use disorders for:

- Initiation of buprenorphine or methadone

- Management of withdrawal (alcohol, opioids, benzodiazepines)

- Discharge planning with linkage to outpatient treatment or harm reduction

- Provide recommendations to primary teams on:

- Pain control in opioid‑tolerant patients

- Antibiotic duration for endocarditis in people who inject drugs

- Management after overdose

Student roles typically:

- Shadowing consults and daily rounds

- Sitting in on family meetings or goals‑of‑care discussions

- Helping with follow‑up calls to clinics or community programs

- Observing (and eventually practicing) brief motivational interviewing under supervision

Clinical exposure:

- Endocarditis, osteomyelitis, soft tissue infections

- Complicated withdrawal courses

- Patients cycling in and out of the hospital with recurrent overdoses

This is “high acuity, high complexity” exposure, but student autonomy is limited. You are embedded in a medical team more than in a classic harm reduction environment.

2. Office‑Based Opioid Treatment (OBOT) and Addiction Clinics

Usually primary care or behavioral health clinics offering:

- Buprenorphine or methadone prescribing

- Naltrexone, disulfiram, or other addiction pharmacotherapy

- Integrated mental health and social work support

Student roles:

- Rooming patients, vitals, and structured screening (PHQ‑9, GAD‑7, AUDIT, DAST)

- Observing physician visits, especially initiation or adjustment of medications

- Participating in case conferences with addiction psychiatrists, social workers, and nurses

- Helping with registry management (tracking no‑shows, lapses in treatment, urine tox trends)

You see longitudinal recovery trajectories instead of just crises. This is where you learn how chronic and relapsing these conditions really are.

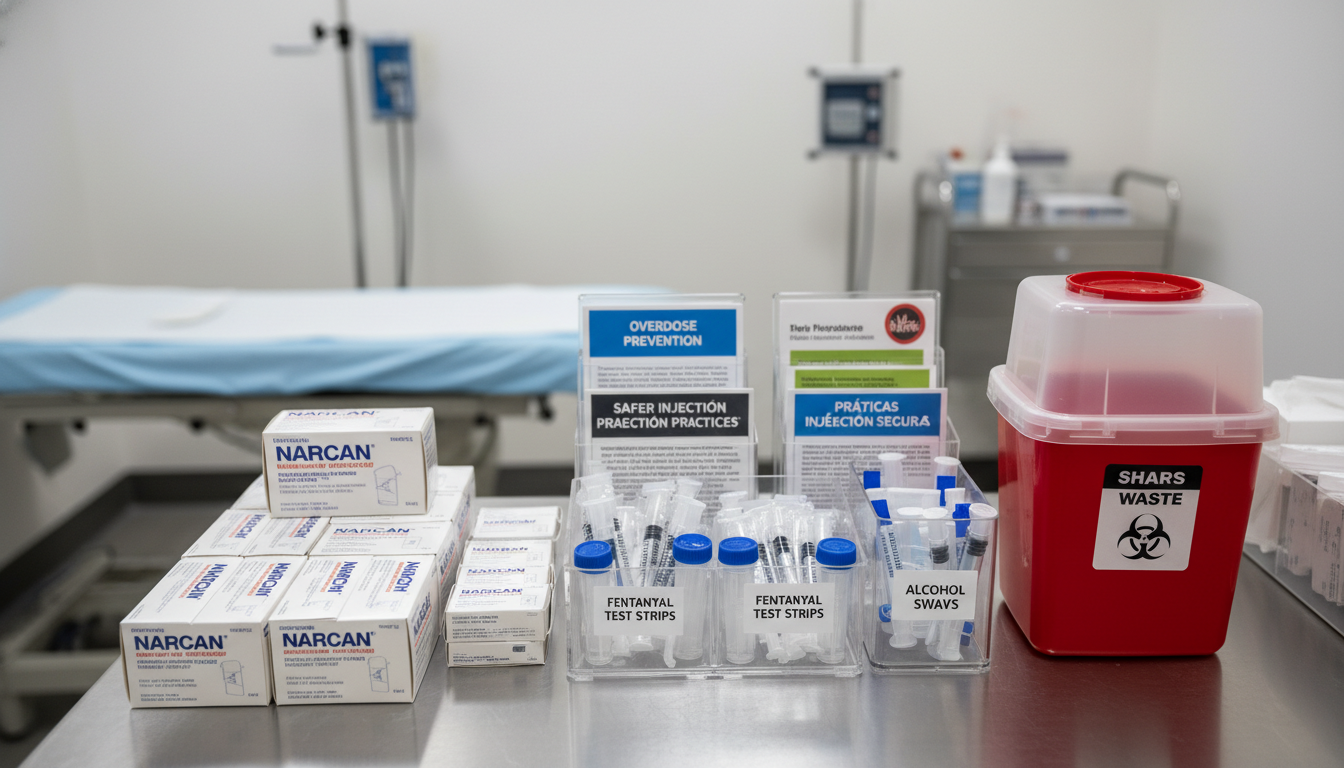

3. Community Harm Reduction Programs

Examples:

- Syringe services programs (SSPs)

- Naloxone distribution projects

- Mobile outreach vans

- Drop‑in centers integrated into shelters or community organizations

These are usually the most accessible for premeds and early medical students and the most aligned with pure harm reduction.

Core activities:

- Distributing sterile syringes, cookers, cottons, sterile water, alcohol pads

- Exchanging used injection equipment, managing sharps containers

- Providing naloxone kits and overdose response training

- Fentanyl test strip distribution and interpretation guidance

- HIV/HCV rapid testing and linkage to confirmatory testing/treatment

- Basic wound assessment triage (within scope) and referrals

Student roles:

- Intake and registration, tracking unique client visits

- Assembling and explaining safer‑use kits

- Conducting structured education under supervision

- Helping with point‑of‑care HIV/HCV tests (in some programs, after training)

- Data collection for program evaluation and research

Risk profile:

- More exposure to active use environments

- Less hierarchical than hospitals—but you must be extremely clear about boundaries and scope

4. Overdose Education and Naloxone (OEND) Programs

Often embedded within:

- EDs

- Community health centers

- College campuses

- Public health departments

Student tasks:

- Screening patients or visitors for overdose risk

- Delivering a structured overdose prevention brief intervention:

- Recognizing overdose

- Rescue breathing and naloxone administration

- Calling EMS

- Documenting kit distribution

- Conducting follow‑up calls or surveys where programs track reversals

These are ideal entry points: highly structured, clear scripts, measurable outcomes.

Concrete Roles for Premeds vs Medical Students

Your training level matters. Programs that blur this do you and patients a disservice.

Premedical Students

Premeds should focus on structured, high‑supervision roles:

Overdose Prevention and Naloxone Education (Scripted)

- Use a standardized training script that has been reviewed by clinicians.

- Practice it with staff before speaking to clients.

- Stay within education, not clinical decision‑making.

Harm Reduction Kit Assembly and Explanation

- Prepare injection kits, safer smoking kits, wound care packets.

- When explaining, stick to approved talking points. Example:

- “Using a new sterile syringe each time reduces your risk of HIV and hepatitis C. Here is how to keep equipment separate and labeled.”

Structured Intake or Screening

- Helping collect demographics, basic substance use patterns, overdose history.

- You are not doing diagnostic assessment. You are following a form.

Program Logistics and Data Support

- Maintaining stock levels, documenting kit distribution, entering anonymous visit data.

- Helping with simple data summaries for grants, QI, or presentations.

Observation of Clinical Encounters

- Shadowing addiction medicine physicians, NPs, PAs, social workers.

- De‑identifying any notes you take for learning.

Where premeds must draw the line:

- No independent counseling beyond approved scripts

- No clinical recommendations (“You should start methadone/buprenorphine”)

- No unsupervised wound care or medical advice

- No promises about detox or housing access you cannot keep

Medical Students (Pre‑clinical and Clinical)

Pre‑clinical students can take on more nuanced communication tasks, usually with direct supervision.

Early Medical Students (MS1–MS2):

- Conducting more open‑ended conversations using:

- Motivational interviewing frameworks (OARS: Open questions, Affirmations, Reflective listening, Summaries)

- Trauma‑informed principles (choice, collaboration, safety, empowerment)

- Helping with:

- Targeted history‑taking about substance use in clinic settings

- SDH screening: housing, food insecurity, legal issues

- In some clinics, basic supervised wound assessment

Clinical Students (MS3–MS4):

With attending oversight, you may:

- Perform more complete substance use histories and present them formally

- Participate in diagnosis discussions under supervision

- Assist in:

- Buprenorphine induction visits

- Methadone maintenance follow‑up

- ED‑based initiation of treatment post‑overdose

- Help manage:

- Linkage to care upon discharge

- Coordination with community harm reduction organizations

Still off‑limits:

- Independent prescribing or medication recommendations

- Independent risk stratification without attending review

- “Therapy” not guided by a structured, evidence‑based approach adopted by the team

Harm Reduction Skills You Can Actually Learn and Practice

Vague “communication skills” are not enough. You should pursue specific, operational competencies.

1. Overdose Risk Assessment (Within Your Role)

Not diagnostic; pattern recognition.

Questions you can be trained to ask:

- “Have you ever overdosed before?”

- “Have you seen someone else overdose?”

- “Do you usually use alone or with others?”

- “Do you ever mix opioids with alcohol, benzos, or other sedatives?”

- “Have you recently been in jail, detox, or the hospital?”

You then:

- Flag high‑risk patterns for the clinical team

- Tailor your naloxone education to the risk profile

- Document responses per program policy

2. Delivering Brief, Structured Education

You should be capable of giving a 5‑minute teaching that is:

- Accurate

- Reproducible

- Respectful

Examples:

Opioid Overdose Education Script Elements:

- How to recognize: pinpoint pupils, slowed or stopped breathing, unresponsiveness

- What to do: stimulate, call 911, rescue breathe, give naloxone, stay with them

- What not to do: put them in a cold shower, inject salt water, leave them alone

Safer Injection Basics:

- New sterile equipment every time

- Not sharing cookers, cottons, or water

- Rotating sites, recognizing early infection signs

- Using test shots to gauge potency in a new supply

3. Trauma‑Informed Interactions

You are not a therapist, but your manner matters.

Key behaviors:

- Ask permission: “Is it OK if I ask a few questions about your substance use?”

- Offer choices: “Would you rather go through the pamphlet together or just take it with you?”

- Avoid sudden physical contact.

- Use non‑shaming language:

- “Person who uses drugs” instead of “addict”

- “Return to use” or “lapse” instead of “dirty” or “failed”

4. Basic Motivational Interviewing Elements

You can practice micro‑skills:

- Reflective listening: “It sounds like you are worried about overdosing but not ready to stop using.”

- Amplified reflection (careful with this): “So using alone feels safer to you than using in a group, even though that might increase your risk if something goes wrong.”

- Eliciting change talk: “On a scale from 1 to 10, how concerned are you about overdosing?” followed by “Why not a lower number?”

You are not “doing MI therapy,” but you are integrating its techniques into every conversation.

Physician Roles You Will See Up Close

Understanding the distinct roles physicians play in addiction medicine will help you frame your volunteering and your personal statement narratives intelligently.

Addiction Medicine Physician as Consultant

Typical scenarios:

- Internal medicine or surgery team consults addiction medicine for:

- Severe alcohol withdrawal management

- Initiation or continuation of methadone/buprenorphine inpatient

- Assistance with a patient leaving AMA due to undertreated withdrawal or pain

What you observe:

- Rapid diagnostic framing: differentiating withdrawal from sepsis, toxic ingestion, or delirium

- Balancing safety, symptom control, and misuse risk

- Negotiating with primary teams that may have limited addiction training

Takeaway: This is high‑cognitive, high diplomacy work. Lots of guideline application, risk–benefit calculation, and stigma navigation.

Addiction Physician as Longitudinal Clinician

In OBOT or integrated primary care:

- Following patients every 1–4 weeks early, then spacing out

- Monitoring:

- Cravings

- Use patterns

- Urine drug screens

- Co‑occurring psychiatric disorders

- Managing chronic pain alongside opioid use disorder

- Coordinating with therapists, case managers, legal systems

You will see:

- Long arcs of improvement and relapse

- How small system changes (e.g., reminder calls) alter retention rates

- The emotional labor of maintaining boundaries while staying empathic

Addiction Physician as Public Health Advocate

In harm reduction‑heavy settings, many addiction physicians:

- Work with local health departments on SSPs and OEND

- Contribute to policy analysis: supervised consumption sites, decriminalization, pharmacy naloxone

- Design and interpret program data to shape practice and policy

For a student, this is your window into:

- How a single QI project on naloxone co‑prescribing can change ED overdose rates

- How research questions emerge directly from community program gaps

How to Choose High‑Quality, Ethical Volunteering Opportunities

Do not sign up for the first “addiction volunteering” role you find. Vet programs carefully.

Ask these concrete questions:

Who supervises me?

- Is there an on‑site clinical lead (physician, NP, PA, RN, LCSW)?

- What is their accessibility when complex situations arise?

What exactly is my scope?

- Written role description?

- Clear boundaries about advice, counseling, physical contact, and documentation?

What training is required before I interact with clients?

- Overdose response protocol

- Confidentiality and HIPAA considerations

- Safety procedures for outreach or street‑based work

How do you measure program outcomes?

- Overdose reversals, linkage to treatment, HIV/HCV tests performed, retention in services?

- Evidence that the work is part of an organized public health strategy, not just optics?

What support exists for vicarious trauma and burnout?

- Regular debriefs?

- Access to supervision when you feel overwhelmed?

Programs that cannot answer these with specificity are not good training grounds for serious clinical volunteers.

Practical Steps to Get Started, Phase by Phase

As a Premed

Educate yourself first

- Read clinical, not just popular, sources:

- CDC guidance on syringe services programs

- SAMHSA materials on medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD)

- ASAM (American Society of Addiction Medicine) public resources

- Read clinical, not just popular, sources:

Identify local harm reduction and addiction medicine programs

- University hospital addiction consult or clinic

- County public health SSP or Naloxone program

- FQHCs (Federally Qualified Health Centers) with OBOT

- Reputable community‑based organizations with clinical partners

Present yourself clearly

- Emphasize:

- Reliability with schedule

- Willingness to do unglamorous tasks (data entry, kit assembly, setup/cleanup)

- Respect for boundaries and eagerness to receive feedback

- Emphasize:

Start in structured roles and grow

- Begin with logistics, data, scripted education

- As trust builds, seek more client‑facing roles with supervision

As a Medical Student

Formal electives and rotations

- Addiction medicine consult elective (often 2–4 weeks)

- Outpatient addiction clinic elective

- Public health/harm reduction selective

Longitudinal involvement

- Join or help build a student‑run addiction or harm reduction clinic with real clinical oversight

- Maintain a consistent weekly presence; this matters more than short bursts of intense involvement

Academic integration

- QI or research linked to your volunteering:

- Naloxone distribution outcomes

- Screening implementation in a primary care clinic

- Linkage‑to‑care rates from ED to OBOT

- Present at local or national meetings (ASAM, ADFM, SGIM) when appropriate

- QI or research linked to your volunteering:

Safety, Boundaries, and Emotional Realities

Addiction‑focused clinical volunteering exposes you to:

- Overdose deaths of people you have met

- Relapse after apparent “success”

- Harsh systemic failures: no detox beds, punitive legal environments, homelessness

You must:

- Have clear debrief channels with supervisors.

- Recognize and name your own frustration or grief early.

- Understand that your role is not to “save” people but to:

- Offer tools

- Reduce immediate risk

- Maintain a humane connection, regardless of outcome

Good programs normalize this, not pathologize it.

Summary: The Three Things to Remember

- Harm reduction is not the fringe of addiction medicine; it is the front door. As a premed or medical student, this is where your volunteering should begin.

- Your roles should be specific, structured, and supervised: overdose education, harm reduction kit distribution, basic screening, and observation of addiction clinicians.

- Seek programs that respect boundaries, use data, and integrate clinicians. That is where you will learn real addiction medicine, not just its rhetoric.

FAQ (Exactly 6 Questions)

1. Will clinical volunteering in harm reduction “look bad” to conservative medical schools or residency programs?

No. At reputable institutions, harm reduction work is viewed as serious, systems‑level public health engagement, especially when done through structured programs with clinical supervision. You can frame it in your applications by emphasizing measurable outcomes (number of naloxone kits distributed, overdose reversals, HIV tests performed) and skills gained (motivational interviewing, trauma‑informed care, interdisciplinary teamwork). Programs that view this negatively are usually demonstrating their own knowledge gaps, not exposing a problem with your experience.

2. How do I talk about harm reduction volunteering without sounding like I am condoning drug use?

Focus on outcomes and ethics. You are not endorsing substance use; you are reducing predictable, preventable harms: overdose, HIV, hepatitis C, serious soft tissue infections. Explain that harm reduction is analogous to other standard public health interventions: condoms do not “endorse” sex, seatbelts do not “endorse” car crashes. You work to keep people alive long enough to access treatment if and when they are ready, while preserving dignity and trust.

3. Can I do physical exams or wound care as a premed or early medical student in these settings?

Generally, no—unless you are part of a structured student‑run clinic or outreach team with clear protocols and direct clinical supervision. Even then, your role might be limited to simple tasks like cleaning superficial wounds after formal training. Anything beyond that (incision and drainage, antibiotic decisions, assessing systemic illness) must be done by licensed clinicians. When in doubt, step back and ask the supervising physician or nurse.

4. How do I handle conversations when someone directly asks me for medical advice I am not qualified to give?

Use a consistent, honest script. For example: “I am a volunteer / medical student, not a licensed clinician yet, so I cannot give medical advice. What I can do is connect you with our nurse/doctor or help you get an appointment where you can discuss this in detail.” Do not guess, do not improvise treatments, and do not let discomfort push you into making promises you cannot keep. Your credibility depends on this.

5. Is it safe to volunteer in syringe services or street‑based harm reduction as a student?

With appropriate programs and training, yes. Established SSPs and outreach teams have clear safety protocols: pairing volunteers, avoiding active crime scenes, having de‑escalation plans, and maintaining physical boundaries. You should receive orientation on what to do if you feel unsafe, how to handle aggressive behavior, and how to manage accidental exposures (e.g., needlestick). If a program cannot articulate these policies clearly, reconsider volunteering there.

6. How can I turn my harm reduction volunteering into a strong research or QI project?

Start by asking the program leadership what data they already collect and what problems they want solved. Common project types include: evaluating naloxone distribution’s impact on self‑reported overdose reversals; tracking linkage‑to‑care rates from an ED OEND program to addiction clinics; analyzing missed appointment patterns in MOUD clinics; or implementing and assessing a standardized overdose risk screening tool. Keep the scope narrow, work closely with a clinician mentor, and aim for a concrete deliverable: a poster, a local presentation, or a QI report that the program can actually use.