The emergency department is the most honest, unfiltered classroom a pre‑med can walk into.

Most “clinical experiences” shield you. The ED does not. It exposes your strengths, your limits, your blind spots, and sometimes your fantasies about medicine. If you learn to navigate it correctly as a volunteer, it becomes one of the most valuable pre‑med experiences you can have. If you do not, it becomes a glorified transport job with some trauma stories.

Let me break this down specifically: what you can actually do, what you absolutely cannot do, how to protect yourself, and how to extract maximum skill development and application value from emergency department volunteering.

(See also: Clinical Volunteering in Palliative Care: Communication Skills You’ll Gain for more details.)

What Emergency Department Volunteers Actually Do (And Don’t Do)

The first misconception: “I’ll be helping with procedures and seeing crazy trauma.” No. Not as a pre‑med volunteer.

Emergency departments are tightly regulated environments. The roles are defined very clearly by hospital policy, state law, and liability concerns.

Typical Allowed Roles and Tasks

The exact details vary by hospital, but you will almost always see some version of the following:

-

- Providing warm blankets, socks, water/juice if permitted.

- Offering pillows, adjusting bed positions (if trained and allowed).

- Assisting family members with basic needs (locating restrooms, explaining where vending machines or waiting rooms are).

- Sitting with anxious or lonely patients who are stable and cleared for visitors.

- Bringing phone chargers, magazines, or distraction items when policy allows.

That does not sound glamorous. That is the point. Admissions committees know it is not glamorous and know that you showed up anyway.

-

- Escorting patients in wheelchairs to imaging, discharge areas, or other departments when directed by nursing staff.

- Taking specimens (properly labeled by staff) to the lab or blood bank.

- Running forms, picking up supplies, restocking rooms and carts.

- Returning equipment like portable monitors, wheelchairs, and stretchers.

This is where you learn the physical layout of the hospital, how departments interact, and how time pressure feels in real life.

Environment and Room Turnover

- Wiping down surfaces and stretchers with hospital-approved disinfectants after staff has discharged a patient.

- Restocking gloves, gowns, masks, IV start kits, emesis bags, and other low‑risk consumables.

- Making the bed, changing linens, setting the room for the next patient.

This is not “below” you. Many residents and attendings did the same thing as techs or orderlies. You are learning workflow and infection control principles in real time.

Clerical and Communication Support

- Answering family questions within your scope (“Yes, the bathroom is down the hall,” not “Let me interpret your CT scan”).

- Relaying non‑urgent messages from patients to nurses (“Room 12 is asking for a blanket.”).

- Helping with non‑clinical paperwork: handing out survey forms, guiding visitors to check‑in desks, filing non‑medical forms.

You are a communication bridge, not a medical decision-maker. That distinction must be crystal clear.

Supervised Observation

- Standing in the corner of a room, with explicit permission, during procedures or evaluations.

- Observing the triage process, resuscitation bay activity, or family discussions—again only with permission and when appropriate.

- Shadowing a physician, PA, or NP during slower times if your hospital and volunteer coordinator explicitly allow that dual role.

Observation is one of the highest yield components for your development, but it is usually a privilege you earn by being useful and unobtrusive first.

Hard Lines: What You Never Do as a Volunteer

There are absolute “no‑go” zones. Violating these is how volunteers get removed and programs get shut down.

You do not:

- Take vital signs (BP, HR, temp, O2 sat) unless you are in a formal, licensed role (e.g., CNA, EMT) and the hospital has credentialed you for that.

- Touch any medication. That includes handing a pill cup, drawing up medications, running a PCA pump, or retrieving something from an automated medication dispenser.

- Insert or remove anything from a patient: IVs, catheters, nasogastric tubes, Foley bags, dressings (unless instructed in very controlled, low‑risk circumstances like assisting with tape removal).

- Access or chart in the electronic medical record (EMR) unless the hospital has formally granted that privilege, which is rare for pre‑med volunteers.

- Give medical advice, interpret findings, or discuss diagnoses and prognoses with patients or families.

- Move unstable patients or patients connected to complex equipment on your own.

If you are ever unsure, default to not doing the task and asking a nurse or your volunteer supervisor.

The Real Clinical Exposure: What You Actually Learn

The ED is not about procedures for pre‑meds. It is about pattern recognition, team dynamics, and emotional resilience.

Exposure to Undifferentiated Complaints

Most outpatient shadowing shows you “polished” medicine: clear chief complaint, charted history, plan already taking shape.

The ED gives you raw data:

- Chest pain that could be reflux, anxiety, pulmonary embolism, STEMI, or an aortic dissection.

- Shortness of breath that could be pneumonia, asthma, heart failure, COPD exacerbation, or anxiety.

- “Altered mental status” without context at 2 AM.

Even as a volunteer, you begin to see how clinicians:

- Rapidly sort patients into “sick” vs “not sick” with just a glance.

- Ask key “red flag” questions.

- Decide what is urgent, what can wait, and what can be discharged safely.

You are not making any decisions. But you are absorbing a mental framework that will pay off in your first year of medical school when you see similar cases in problem‑based learning or OSCEs.

Acute Decision-Making and Priority Shifts

Watch the ED for 4 hours and you will notice:

- A stable ankle sprain being evaluated in detail.

- Suddenly, overhead: “Code Stroke” or “Trauma activation, ETA 5 minutes.”

- The entire team reorients. The room is prepped. Non‑urgent tasks pause.

Your role will be small: maybe moving a chair, clearing a hallway, or staying out of everyone’s way. But if you pay attention, you will see:

- Task delegation: who leads, who documents, who runs medications.

- Closed‑loop communication: “Give 1 mg epinephrine IV push.” – “1 mg epinephrine IV push given.”

- Conflict under pressure, and how experienced teams manage it (or fail to manage it).

These observations are gold for future interviews when you must talk specifically about teamwork, leadership under pressure, or seeing the “messy side” of medicine.

Seeing Health Systems Reality

The ED is where every system problem eventually shows up:

- Patients using the ER as primary care because they lack insurance.

- Boarding patients for 24‑48 hours because there are no inpatient beds.

- Social crises: homelessness, psychiatric emergencies, substance use, intimate partner violence.

You are not just collecting “interesting cases.” You are seeing structural barriers to care in real time.

That matters for your future:

- Personal statements that describe systems-level insight stand out.

- Interview narratives that show you understand burnout, boarding, and safety‑net medicine are far more compelling than “I saw a dramatic trauma.”

Risks: Physical, Ethical, Emotional, and Legal

If you treat ED volunteering like a shadowing shift with a free T‑shirt, you will miss the risk profile entirely.

Physical and Infectious Risks

You will be in a high‑exposure environment. Respiratory infections, GI pathogens, blood and body fluids. Some specifics:

Infection Risk

- COVID‑19, influenza, RSV, TB, C. difficile, norovirus—these circulate constantly.

- Needle sticks and sharps injuries are rare for volunteers (you should never be handling sharps), but body fluid exposure can happen if you are careless.

Mitigation:

- Follow PPE guidelines without exception. That means masks, eye protection when indicated, gloves when contacting anything contaminated.

- Do not enter isolation rooms unless staff explicitly requests it and you are trained on the appropriate precautions.

- Hand hygiene becomes non‑negotiable: foam in, foam out, and handwashing after any contamination.

Environment and Ergonomic Risks

- You will walk thousands of steps per shift. Poor footwear and posture will punish you.

- Moving wheelchairs or beds incorrectly can strain your back.

Solution: athletic/clinical shoes, learn proper body mechanics from nursing staff, and speak up if a transfer seems unsafe for one person.

Emotional and Psychological Risks

You will see distressing things. Common flashpoints:

- Sudden death of relatively young patients.

- Traumatic injuries, sometimes with graphic visual details you can never “unsee.”

- Crying family members in waiting rooms, sometimes wailing in grief.

- Intoxication, agitation, or violent behavior from patients.

Reactions vary:

- Some students feel numb and concern themselves with being “unbothered” or “tough.” That is not resilience. It is avoidance.

- Others experience intrusive imagery afterward, trouble sleeping, or emotional lability.

Practical strategies:

- Debrief with your volunteer coordinator or a trusted staff member after particularly difficult events. Short and focused: “That was a lot; can I ask you one or two questions about what happened?”

- Be honest with yourself. If you notice persistent distress, nightmares, or dread before shifts, contact your program coordinator or counseling services at your institution. This is not weakness; it is the most basic form of self‑monitoring you will need as a clinician.

- Set boundaries. If your hospital allows you to step out of a room that is particularly triggering (e.g., pediatric codes), know that this is acceptable as a volunteer. Tell staff you are stepping out for a moment; do not disappear silently.

Ethical and Privacy Risks

HIPAA is not a theoretical concept in the ED. It is tested constantly.

You must:

- Never discuss identifiable patient information outside the clinical area, especially in elevators, cafeterias, or public transit.

- Never share cases on social media, even if you anonymize them. Small details can be identifiable.

- Never access, photograph, or record anything in the ED environment on your personal device.

Crossing these lines can get you expelled from the program and may have professional consequences. Hospitals have zero tolerance here, especially in the age of viral posts.

Legal and Scope Risks

Your legal protection as a volunteer is tied directly to staying within your defined role.

- Do not “help” with tasks you are not trained and cleared for, even if a stressed resident suggests it. A common example: “Can you help me hold this patient while I insert this line?” If physical restraint is involved, that is risky and should be staff‑only.

- If a patient or family asks you for medical advice, your script should be automatic: “I am a volunteer, not a medical professional. I can ask your nurse or doctor to come speak with you.”

If an incident occurs (fall, injury, complaint), notify your supervisor immediately and document what occurred according to hospital policy. Do not attempt to “fix” it yourself.

How to Actually Build Skills as a Pre‑Med in the ED

You are not there just to be “around medicine.” You are there to practice concrete pre‑professional skills that admissions committees value.

Skill 1: Clinical Communication with Non‑Clinicians

Your main interactions will be with patients and families, not with physicians. That is in your favor.

Focus on developing:

Plain‑Language Explanations of Non‑Medical Processes

- “The nurse is with another patient right now; I will let them know you are waiting.”

- “The doctor may be waiting on lab results before coming back to talk with you. That can take a bit of time.”

- “I do not have access to your test results, but I can find a staff member who might be able to update you.”

You are learning to be clear, honest, and calm without overpromising.

Listening Under Stress

- Patients may repeat the same question multiple times.

- Families will vent frustration about wait times, perceived neglect, or previous experiences.

Your task is not to argue or defend. It is to listen, validate their frustration without agreeing to inaccurate statements, and connect them with staff.

Boundary Setting in Conversation

- If a patient starts asking, “What would you do? Do you think this is serious?” you redirect:

- “I really am not qualified to answer that. I want to make sure your doctor or nurse explains that part.”

- If a patient starts asking, “What would you do? Do you think this is serious?” you redirect:

You are building a foundation for the exact skills used in OSCEs and later in residency: empathic yet boundaried communication.

Skill 2: Situational Awareness and Anticipation

Good ED volunteers anticipate needs. This is a trainable skill.

Concrete examples:

- Before a trauma activation, staff may want:

- Clear hallways.

- An empty, clean stretcher.

- Extra blankets ready.

- Gloves and gowns stocked outside the room.

If you learn your department’s patterns, you can quietly set these up without being asked. Over time, nurses will trust you more, which often increases your observational opportunities.

Pay attention to:

- Which rooms are used for which kinds of patients (isolation rooms, resus bays, psych holds).

- Where key supplies are kept and how often they run low.

- When routine bottlenecks occur (shift change, radiology delays).

Situational awareness is one of the most underrated skills in early medical training. Start practicing it now.

Skill 3: Emotional Regulation and Professional Demeanor

Most pre‑meds are used to academic stress, not acute emotional stress.

Use ED shifts to consciously practice:

- Neutral facial expressions during distressing situations (without appearing cold).

- Speaking slowly and with measured tone when others are agitated.

- Simple grounding techniques for yourself after intense events: a brief walk, deep breathing, deliberate handwashing as a reset routine.

One meta‑skill: learn to ask for feedback in a professional way. For example, after a few weeks, ask a nurse you work with often:

“Is there anything I could be doing differently as a volunteer that would make things easier for you or the patients?”

You will get responses like “Speak a little louder when you call for help” or “Always announce yourself before entering curtain spaces.” These are not trivial details; they are professional polish.

Choosing an ED Volunteer Program and Setting Expectations

Not all ED volunteering experiences are equal. The same title on a resume can mean completely different day‑to‑day realities.

Key Questions to Ask Before You Commit

When you interview or apply for a hospital ED volunteer role, ask:

- “What are the typical tasks ED volunteers perform on a shift?”

- “How much direct patient interaction should I expect?”

- “Are volunteers allowed in patient rooms? Under what circumstances?”

- “Are there opportunities to observe procedures or resuscitations, and if so, how is that handled?”

- “What is the minimum time commitment, and can shifts be scheduled consistently (e.g., same day each week)?”

Red flags:

- Vague answers like “You will just help wherever needed.”

- No mention of training or orientation.

- No clear staff point‑person (charge nurse, volunteer coordinator).

Programs that know what they are doing will describe specific expectations and boundaries.

Time Commitment: What Actually Looks Serious on Applications

Admissions committees care more about consistency than volume alone.

Typical baseline expectations that look credible:

- One 3–4‑hour shift per week, sustained for at least 6–12 months.

- Modest seasonal breaks for exams or vacations are fine, but disappearing for months and reappearing just before application season is not.

If you can commit 150–200+ hours over a year or two, you can credibly discuss longitudinal insight: how the ED changes seasonally, patterns you saw repeatedly, and your own personal growth.

Integrating ED Volunteering with Other Clinical Experiences

ED experience is powerful, but it is not the only clinical exposure you should have.

Strategically, ED volunteering pairs well with:

- Primary care shadowing – shows you see both acute and longitudinal care.

- Inpatient medicine volunteering (on a ward) – illustrates understanding of admission flow and chronic illness management.

- Free clinic or community health – demonstrates awareness of outpatient safety‑net care and social determinants of health.

When you apply, this allows you to say something like:

“In the emergency department I saw the acute consequences of uncontrolled diabetes; in primary care and community clinics I saw the upstream failures that led there.”

That is the level of integration that distinguishes a mature applicant from one who just “collected hours.”

How to Reflect and Write About ED Volunteering

Experience without reflection is just noise. You will be competing with thousands of applicants who also “volunteered in the ER.”

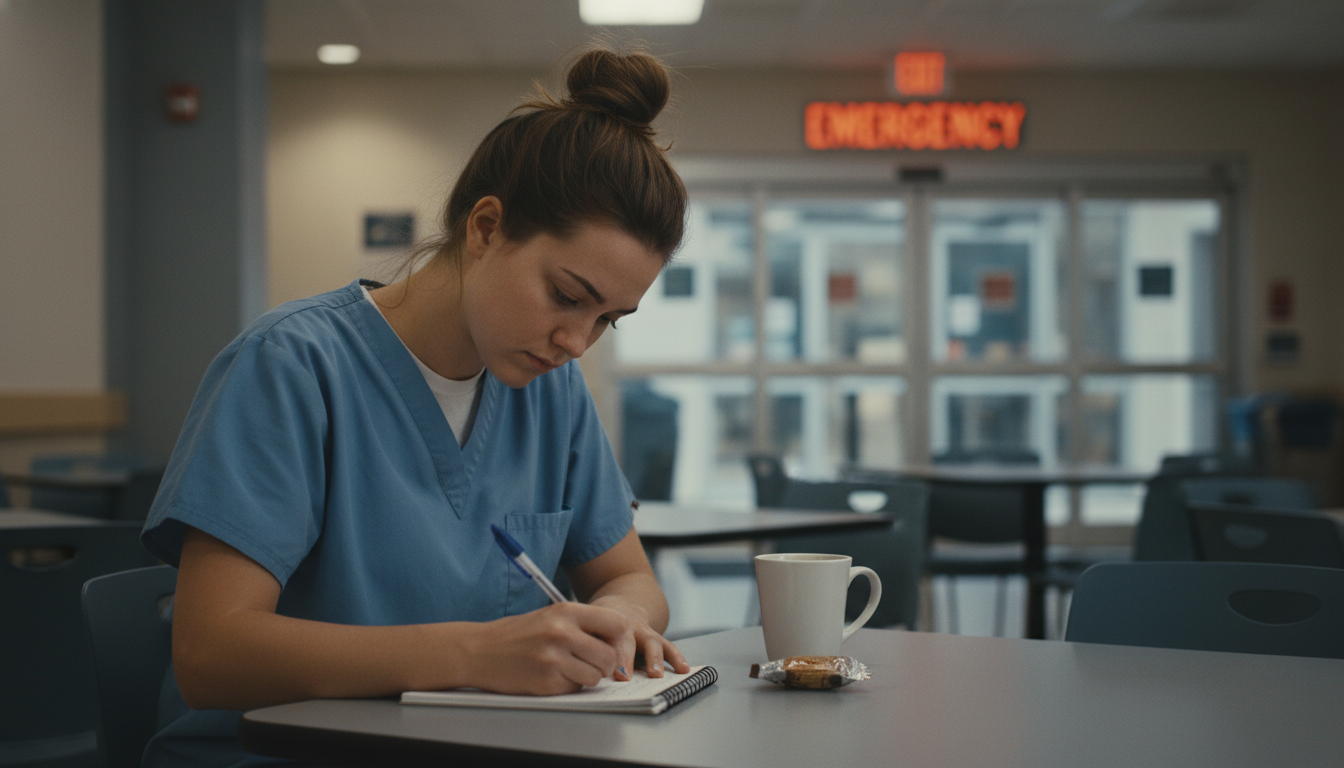

Building a Reflection Habit During the Experience

After each shift, take 5–10 minutes and write down:

- 1–2 memorable patient interactions (fully de‑identified).

- 1 team interaction you observed (good or bad).

- 1 emotion you experienced, especially if it surprised you.

- 1 concrete skill you practiced (even if minor: “introduced myself clearly,” “handled a frustrated family member without escalating”).

Do not wait until application season to remember. Memory will compress everything into “It was busy, I learned a lot.”

You want granular detail like:

“Middle‑aged man with chest pain, anxious, pacing. I was asked to sit with him while waiting for repeat enzymes. He talked mostly about work stress and being the sole provider. I was surprised that what he needed most was someone to help him feel less alone in a hallway stretcher.”

These details become the scaffolding for powerful application content.

Translating Experiences into Application Narratives

When describing ED volunteering in secondaries or at interviews:

Avoid generic statements

- Weak: “I learned the importance of teamwork and communication.”

- Stronger: “During a trauma activation, I watched the attending lead a room of 12 people with clear, closed‑loop commands, while the charge nurse quietly managed room flow and supplies. I recognized that effective care depended less on individual heroics and more on practiced systems.”

Highlight specific skills, not just emotions

- Talk about learning to communicate boundaries with patients.

- Explain how you handled being asked for medical advice you were not qualified to give.

- Describe how you integrated feedback from staff into how you approached new shifts.

Show progression over time

- Early: “I was mostly focused on not being in the way.”

- Later: “I started anticipating room turnover needs, taking initiative on restocking, and nurses began to ask specifically for my help on busy nights.”

Committees are looking for evidence of growth, self‑awareness, and a realistic understanding of clinical work.

When ED Volunteering Might Not Be the Right Fit

Emergency medicine is not for everyone. That is not a problem; it is information.

ED volunteering might be poorly matched for you if:

- You find chaotic, noisy environments overwhelming despite repeated exposure and coping attempts.

- Night or evening shifts severely destabilize your sleep and academic performance.

- Graphic injuries or sudden death cause persistent intrusive thoughts or distress that does not ease with time or support.

- You realize your interests lean strongly toward longitudinal relationships and slower‑paced settings.

If that is you, pivot. Admissions committees do not require ED exposure specifically. They require meaningful, sustained clinical exposure that you can articulate clearly.

Options:

- Inpatient ward volunteering with more predictable rhythms.

- Oncology clinics, where long‑term relationships are central.

- Primary care offices or community health centers.

Choosing not to continue in the ED because it clashes with your temperament is a sign of insight, not weakness. You still gained valuable information about your fit in different clinical environments.

Three Things to Remember

Your scope is narrow on purpose. Respecting that scope is not a limitation; it is the first test of your professionalism and judgment.

The value comes from observation and reflection, not drama. Restocking rooms and bringing blankets, when combined with careful watching and structured reflection, will teach you more about real medicine than one spectacular trauma case.

Consistency beats intensity. A year of steady 3‑hour shifts, with active skill‑building and feedback, is far more impressive and transformative than a brief, high‑volume burst of ED hours done purely for checkbox purposes.