Introduction: Nanotechnology as a Catalyst for Drug Delivery Innovation

Nanotechnology is rapidly reshaping how clinicians and scientists think about treating disease. By engineering materials at the scale of atoms and molecules, it is now possible to design smarter drug delivery systems that can seek out specific tissues, release their payloads in a controlled manner, and dramatically improve drug bioavailability. For medical students, residents, and early-career clinicians, understanding these Healthcare Innovations is increasingly important—not just for exams and research, but for informed, ethical practice in a field that is changing quickly.

From Targeted Therapies in oncology to RNA-based treatments and long-acting depot formulations for chronic disease, nanotechnology sits at the intersection of pharmacology, biomedical engineering, and clinical medicine. This article explores the science behind nanotechnology in drug delivery, highlights key clinical applications, and discusses the safety, ethical, and regulatory questions that future physicians will need to navigate.

Nanotechnology Fundamentals: Working at the Nanoscale

Nanotechnology refers to the design, manipulation, and application of materials and devices with at least one dimension between 1 and 100 nanometers (nm). At this scale, materials often behave differently than they do in bulk form because of:

- Extremely high surface area–to–volume ratios

- Quantum effects that alter optical, electrical, or magnetic properties

- Changes in solubility, reactivity, and mechanical strength

To appreciate the scale: a nanometer is one-billionth of a meter; a typical human hair is about 80,000–100,000 nm wide. Yet within this tiny space, we can package drugs, targeting ligands, imaging agents, and sensors into a single engineered particle.

Why Nanoscale Matters for Drug Delivery

For drug delivery, nanoscale engineering offers several major advantages:

- Enhanced drug solubility: Poorly water-soluble drugs can be formulated as nanocrystals or loaded into nanocarriers, improving dissolution and absorption.

- Improved stability: Labile drugs such as peptides, proteins, and nucleic acids can be protected from enzymatic degradation.

- Cell and tissue targeting: Nanoparticles can be functionalized with antibodies, peptides, or small molecules that selectively bind receptors overexpressed on diseased cells.

- Controlled and sustained release: Carrier composition can be engineered to release drugs over hours, days, or even months.

- Multifunctionality: A single nanoparticle can integrate therapy and diagnostics (“theranostics”), enabling real-time monitoring of treatment.

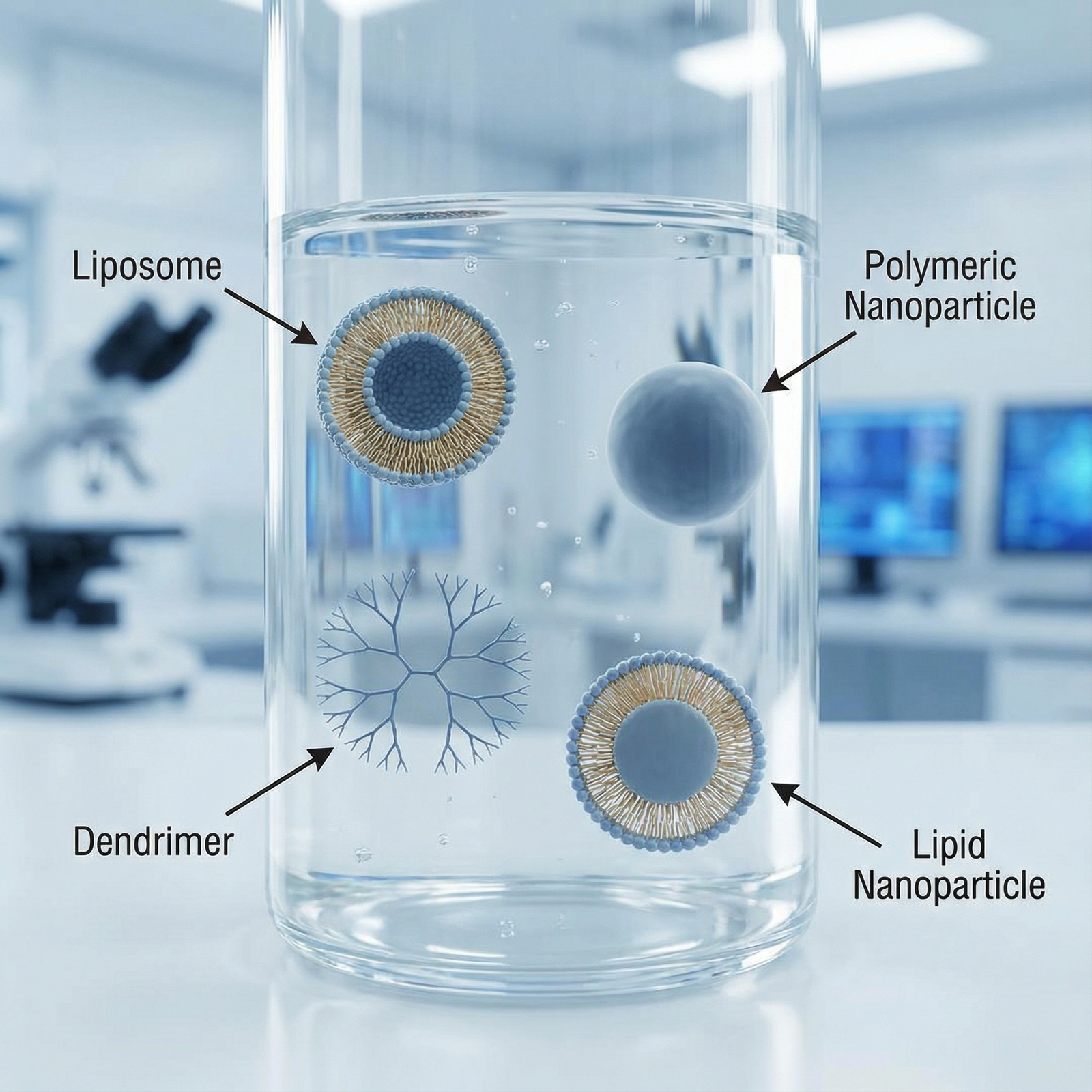

Key Types of Nanomaterials in Drug Delivery

Several classes of nanomaterials are widely studied and increasingly used in clinical practice:

Nanoparticles (polymeric or inorganic):

Solid colloidal particles (often 10–200 nm) made from biodegradable polymers (e.g., PLGA), metals (e.g., gold), or silica. These can carry hydrophobic or hydrophilic drugs.Nanocapsules:

Core–shell structures where the drug is confined to a cavity surrounded by a polymer or lipid membrane, useful for protecting unstable drugs.Nanospheres:

Matrix systems in which the drug is uniformly dispersed throughout a solid polymeric core, enabling sustained and controlled release.Liposomes:

Spherical vesicles consisting of one or more phospholipid bilayers. They can encapsulate hydrophilic drugs in their aqueous core and hydrophobic drugs in their lipid bilayer. Long-circulating (PEGylated) liposomes are already used clinically (e.g., liposomal doxorubicin).Dendrimers:

Highly branched, tree-like macromolecules with a central core and multiple functional end groups. Their precise structure allows for controlled drug loading and surface modification for targeting.Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs):

Solid or semi-solid lipid-based particles used prominently for nucleic acid delivery (e.g., mRNA vaccines), offering protection and efficient cellular uptake.

Understanding these platforms—and their pros and cons—helps clinicians interpret emerging literature and evaluate which technologies are most appropriate for particular clinical problems.

Core Advantages: How Nanotechnology Transforms Drug Delivery

Targeted Drug Delivery and Precision Therapy

Traditional systemic therapies often distribute drugs throughout the body, leading to:

- Non-specific exposure of healthy tissues

- Dose-limiting toxicity

- Suboptimal drug concentrations at the target site

Nanotechnology enables targeted drug delivery, where carriers are engineered to preferentially accumulate at the disease site.

Passive vs Active Targeting

Passive targeting:

Relies on physiological differences such as the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumors, where leaky vasculature allows nanoparticles (typically 50–200 nm) to accumulate more than in normal tissue.Active targeting:

Involves decorating nanoparticle surfaces with ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides, folate) that bind specific receptors overexpressed on target cells, improving cellular uptake.

Case Study: Nanotechnology in Cancer Treatment

Oncology remains the flagship area for nanotechnology in drug delivery:

Albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel):

Paclitaxel is bound to albumin nanoparticles (~130 nm), improving solubility and tumor penetration while avoiding the need for toxic solvents. Clinically approved for breast, lung, and pancreatic cancers.Liposome-based chemotherapy:

PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin prolongs circulation time and reduces cardiotoxicity by altering tissue distribution compared to free doxorubicin.Experimental tumor-targeted nanoparticles:

Albumin or polymer-based nanoparticles are being developed to selectively bind tumor markers such as HER2, EGFR, or integrins, amplifying drug concentration at the tumor while sparing healthy tissues.

For residents, appreciating how nanocarriers change a drug’s pharmacokinetic profile—volume of distribution, clearance, and half-life—is essential for understanding both therapeutic benefit and adverse effects.

Controlled and Sustained Drug Release

Another major contribution of nanotechnology is controlled release, where the drug is released at a predetermined rate over time:

- Reduces peak–trough fluctuations

- Minimizes peak-related toxicity

- Improves adherence by reducing dosing frequency

Release can be engineered by modifying:

- Polymer composition (e.g., lactide:glycolide ratio in PLGA)

- Particle size and porosity

- Degradation kinetics (e.g., biodegradable vs non-degradable materials)

- Stimuli-responsiveness (pH, temperature, enzymes, light, or magnetic field)

Example: Biodegradable Polymeric Nanoparticles in Chronic Disease

Biodegradable nanoparticles made from PLGA or similar polymers can:

- Encapsulate drugs for hypertension, diabetes, or psychiatric conditions

- Release them gradually over weeks to months

- Be administered as injections or implantable depots

For example, long-acting antipsychotic formulations use nanostructured delivery systems to maintain steady serum levels, reducing relapse risk in patients with poor oral adherence.

Enhancing Bioavailability of Poorly Soluble Drugs

A significant proportion of new chemical entities are poorly water soluble (Biopharmaceutics Classification System Class II and IV). Nanotechnology offers multiple strategies to improve oral and parenteral bioavailability:

Nanocrystals and nanosuspensions:

Reducing drug particles to the nanometer range increases surface area, enhancing dissolution rate and absorption.Encapsulation in lipid or polymeric carriers:

Improves solubilization in biological fluids and can facilitate lymphatic transport, bypassing first-pass metabolism.

Example: Statins and Nanocrystal Technology

Some statins have limited water solubility and variable absorption. Nanocrystal formulations:

- Increase dissolution in gastrointestinal fluids

- Enhance Cmax and AUC without needing higher doses

- May allow for dose reduction while maintaining therapeutic effect

Similar approaches are being explored for antifungals, anti-HIV drugs, and oncology agents, especially where conventional formulations require high doses or toxic excipients.

Real-World Applications of Nanotechnology in Modern Healthcare

Drug-Loaded Nanoparticles Across Specialties

Drug-loaded nanoparticles have been studied or used in multiple systems:

Oncology:

Nanoparticle formulations of docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cisplatin demonstrate improved tumor targeting and reduced systemic toxicity in preclinical and early clinical studies.- Example: Docetaxel-loaded PLGA nanoparticles in breast cancer models show enhanced tumor uptake and cytotoxicity compared with free docetaxel, potentially enabling lower dosing.

Cardiovascular disease:

Nanoparticles can deliver thrombolytic agents directly to clot sites, reduce bleeding risk, or provide localized delivery of anti-proliferative agents to prevent restenosis after stenting.Infectious diseases:

Nanocarriers for antiretrovirals or antitubercular drugs aim to improve tissue penetration (e.g., into macrophages or the CNS) and reduce dosing frequency.Neurology and psychiatry:

Nanoparticles are being optimized to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB), using targeting ligands or exploiting receptor-mediated transcytosis, for conditions such as glioblastoma, Alzheimer disease, and depression.

For clinicians, the key is recognizing how nanoparticle formulation may change dosing, toxicity, and monitoring requirements compared with conventional drugs.

Gene Therapy and Nucleic Acid Delivery

Delivering nucleic acids (DNA, siRNA, mRNA) safely and efficiently has historically been a major challenge. Nanotechnology has become central to overcoming biological barriers such as:

- Degradation by nucleases

- Poor cellular uptake

- Endosomal entrapment

Lipid-based and polymeric nanocarriers can protect nucleic acids and promote intracellular delivery.

Landmark Example: Lipid Nanoparticles in mRNA Vaccines

The COVID-19 vaccines by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna are now classic examples of nanotechnology-enabled Healthcare Innovations:

The mRNA is encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles that:

- Protect it from degradation

- Facilitate fusion with cell membranes

- Promote endosomal escape and cytoplasmic release

The result: Efficient transient expression of the viral spike protein, robust immune responses, and a scalable, adaptable platform for future vaccines.

Beyond vaccines, LNPs and other nanocarriers are being explored to deliver:

- siRNA for gene silencing (e.g., in transthyretin amyloidosis)

- CRISPR–Cas9 components for gene editing

- mRNA for protein replacement therapies

Understanding these systems is critical for future clinicians who may counsel patients receiving nanoparticle-based genetic therapies.

Antibody–Drug Conjugates and Nanotechnology

Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) use a monoclonal antibody linked to a cytotoxic payload, targeting specific antigens on tumor cells. While ADCs themselves are not always “nanoparticles” in the traditional sense, nanotechnology influences:

- Linker chemistry (stability in circulation vs release in the tumor microenvironment)

- Payload design and size

- Optimization of pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution

Some emerging platforms combine antibodies with nanoparticle carriers, effectively creating “nano-ADCs” that can deliver multiple drug molecules, imaging agents, or synergistic payloads simultaneously.

Challenges, Safety, and Ethical Considerations in Nanomedicine

Despite the promise, there are significant scientific, practical, and ethical challenges that every healthcare professional should recognize.

Safety, Toxicity, and Long-Term Effects

Key concerns include:

Off-target accumulation:

Nanoparticles can accumulate in the liver, spleen, or other organs, raising questions about chronic exposure and long-term toxicity.Immunogenicity and hypersensitivity:

Some nanomaterials or surface chemistries (e.g., PEG) can trigger immune reactions, from mild infusion reactions to severe anaphylaxis.Degradation products:

Biodegradable polymers eventually break down into monomers (like lactic and glycolic acid). While generally considered safe, local accumulation or unexpected interactions may occur.Crossing biological barriers:

The ability of nanoparticles to cross the BBB or placental barrier could be both therapeutic and harmful if not carefully controlled.

Ethically, introducing new nanotechnologies into patient care requires transparent communication about known risks, knowledge gaps, and realistic expectations of benefit.

Regulatory and Manufacturing Hurdles

Regulatory agencies such as the FDA and EMA are still refining guidance for nanomedicines. Challenges include:

- Defining what constitutes a “nanomedicine” from a regulatory standpoint

- Establishing standardized characterization methods (size, charge, polydispersity, surface chemistry)

- Ensuring reproducible manufacturing at scale with tight quality control

- Managing complex comparability assessments when making changes to manufacturing processes

For residents involved in clinical trials or drug development, familiarity with these issues is valuable, especially when interpreting safety data and informed consent language.

Cost, Access, and Health Equity

Nanotechnology-based drugs can be significantly more expensive than conventional formulations due to:

- Complex synthesis and purification

- Specialized equipment and expertise

- Intellectual property considerations

This raises important questions in medical ethics and health policy:

- Will nanomedicines widen or narrow existing disparities in healthcare access?

- How should clinicians balance cost-effectiveness with potential incremental benefits?

- What obligations do healthcare systems have to ensure equitable access to innovative therapies?

Engaging with these questions is part of responsible Personal Development and Medical Ethics for future physicians.

Public Perception and Professional Education

Misconceptions about “nanobots” or fears about “unknown particles” can influence patient acceptance. On the professional side, many clinicians receive limited formal training in nanotechnology. To bridge this gap:

- Undergraduate medical curricula can integrate basic nanomedicine concepts into pharmacology and therapeutics.

- Residents can seek electives or research experiences in translational nanomedicine.

- Clinicians should stay informed through continuing education, as nanoparticle-based therapies become more common in oncology, infectious disease, and immunology.

Practical Takeaways for Medical Students and Residents

For learners and early-career clinicians, nanotechnology in drug delivery is not just a research curiosity—it is already altering standard of care in several fields.

How to Interpret Nanomedicine Literature

When reading studies involving nanotechnology-based drug delivery, consider:

- What is the carrier? Liposome, polymeric nanoparticle, dendrimer, etc.

- How does it change pharmacokinetics? Half-life, distribution, clearance.

- What is the targeting strategy? Passive vs active targeting, ligands used.

- What endpoints are improved? Efficacy, toxicity profile, adherence, quality of life.

- Are there unique adverse events? Infusion reactions, organ-specific accumulation.

This structured approach will help you critically appraise claims about “revolutionary” nano-formulations.

Clinical Scenarios Where Nanotechnology Matters

Examples of real or emerging scenarios:

- Choosing between conventional vs liposomal doxorubicin in a patient with high cardiac risk.

- Explaining to a patient how an mRNA vaccine uses lipid nanoparticles and addressing safety concerns.

- Considering long-acting injectable nanoparticle formulations for patients with severe adherence challenges.

- Participating in a tumor board where clinical trial options include nanoparticle-based chemotherapeutics.

Having a conceptual framework for how nanotechnology impacts drug behavior will support better shared decision-making.

Ethical Practice in the Era of Nanomedicine

Clinicians should strive to:

- Provide balanced, evidence-based counseling about benefits and uncertainties.

- Respect patient autonomy, especially when data are still evolving.

- Advocate for equitable access to clinically meaningful innovations.

- Reflect on potential biases (e.g., favoring “high-tech” options without sufficient incremental benefit).

Aligning technologically advanced care with core medical ethics—beneficence, nonmaleficence, justice, and respect for persons—is essential.

FAQs: Nanotechnology and Drug Delivery in Clinical Practice

1. What is nanotechnology in medicine, and how is it different from traditional pharmacology?

Nanotechnology in medicine involves designing and using materials and devices at the nanoscale (1–100 nm) to improve diagnosis, drug delivery, and therapy. Unlike traditional pharmacology, which largely relies on the chemical properties of drugs themselves, nanomedicine adds a sophisticated delivery vehicle that can:

- Protect the drug from degradation

- Modify distribution in the body

- Enable targeting to specific cells or tissues

- Control release over time

This can transform a known drug’s safety and efficacy profile without changing its active molecule.

2. How does nanotechnology specifically improve drug delivery and bioavailability?

Nanotechnology improves drug delivery and bioavailability through several mechanisms:

- Solubility enhancement: Nanocrystals or encapsulation increase dissolution of poorly soluble drugs.

- Protection from metabolism: Encapsulation shields labile drugs (e.g., peptides, mRNA) from enzymatic degradation.

- Targeting: Surface ligands guide nanoparticles to diseased cells or tissues, increasing local concentration.

- Controlled release: Engineered matrices release drugs slowly, maintaining therapeutic levels and reducing dosing frequency.

Collectively, these features can lower required doses, reduce adverse effects, and improve therapeutic outcomes.

3. What are the main risks or safety concerns associated with nanotechnology-based therapies?

Key safety concerns include:

- Organ accumulation and long-term toxicity, especially in the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes.

- Immune reactions, such as hypersensitivity to nanoparticle components (e.g., lipids, PEG).

- Unexpected off-target effects, especially for carriers capable of crossing barriers like the BBB.

- Limited long-term data for many newer platforms, making post-marketing surveillance crucial.

Clinicians should be vigilant for unique patterns of toxicity and report adverse events through appropriate pharmacovigilance systems.

4. Which nanotechnology-based therapies are already in routine clinical use?

Several nanotechnology-enabled therapies are now standard or widely used, including:

- Liposome-based chemotherapies, such as pegylated liposomal doxorubicin.

- Albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel) for various cancers.

- Lipid nanoparticle mRNA vaccines (e.g., Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines).

- siRNA therapies delivered via lipid nanoparticles for conditions like hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis.

More are in late-stage clinical trials, particularly in oncology, infectious diseases, and rare genetic disorders.

5. How can medical students and residents build competence in nanomedicine and drug delivery innovations?

Practical steps include:

- Integrating nanomedicine topics into self-directed learning in pharmacology and oncology.

- Joining research projects that involve drug delivery systems, gene therapy, or biomaterials.

- Attending seminars or conferences focused on nanotechnology and Healthcare Innovations.

- Practicing evidence-based appraisal of nanomedicine trials in journal clubs.

- Engaging in discussions about cost, access, and ethics surrounding advanced therapeutics.

By combining scientific understanding with ethical reflection, future clinicians can help ensure that nanotechnology in drug delivery is used wisely, safely, and equitably.

Nanotechnology is not just shaping the future of drug delivery—it is already altering current practice. For those training in medicine today, literacy in these emerging technologies will be a key component of competent, patient-centered care in the decades ahead.