Understanding “Malignant” Programs in Pediatrics-Psychiatry

For a DO graduate pursuing Pediatrics-Psychiatry or triple board training, the residency match is already a niche, competitive path. That reality can make it tempting to accept any offer that seems close to what you want. But in no specialty is it worth sacrificing your well-being in a malignant residency program.

A “malignant” program isn’t simply busy or demanding. Every residency is hard. Malignant means chronically unsafe, disrespectful, or exploitative in a way that undermines your training, mental health, and future career. For a DO graduate in pediatrics-psychiatry—often entering programs historically built around MD pipelines—it’s especially important to recognize toxic program signs early.

This article will walk you through:

- What “malignant” means in the context of pediatrics-psychiatry and triple board

- How to interpret residency red flags as a DO graduate

- Specific warning signs during the osteopathic residency match process, interviews, and post-interview contact

- How pediatrics-psychiatry and triple board programs can be uniquely vulnerable to toxicity

- Practical steps to vet programs and protect yourself

What Makes a Residency Program “Malignant”?

A malignant residency program is one where systemic behaviors, culture, and leadership patterns consistently harm residents. It’s not about one difficult rotation or one gruff attending. Malignancy is about repeated, predictable dysfunction.

Common features include:

- Chronic disregard for duty hour rules and safety

- Punitive or retaliatory behavior toward residents

- Hostility toward raising concerns or asking for help

- Persistent psychological mistreatment (bullying, shaming, gaslighting)

- Systematic blocking of career development (letters, electives, research)

These can occur in any specialty, but pediatrics-psychiatry and triple board programs have a few unique risk points:

- Cross-department politics: You’re training across pediatrics, psychiatry, and often child psychiatry. If departments don’t communicate well, residents get caught in the middle.

- Role confusion: Are you primarily “peds,” “psych,” or “triple board”? If the program hasn’t answered that clearly, residents may be pulled in different directions with conflicting expectations.

- Smaller program size: Many peds psych and triple board tracks are tiny. In a small cohort, one malignant leader or one toxic senior can impact your entire experience.

- High emotional load: You’re dealing with children and families in crisis; the work is emotionally heavy. Malignant programs add unnecessary psychological harm.

A demanding program with strong education, supportive leadership, and a clear structure is not malignant. The problem is when intensity is paired with disrespect, chaos, or exploitation.

Global Red Flags for Any Residency (With Peds-Psych Examples)

Before we drill down into specialty-specific issues, it helps to recognize global residency red flags. These are problematic across all programs, including pediatrics-psychiatry and triple board.

1. Chronic Violation of Duty Hours and Safety

If current residents bluntly say, “We’re always over 80 hours but just don’t log it,” you should pause.

Signs to watch for:

- Residents casually mentioning 24+ hour calls plus clinic the next day.

- “We’re expected to come in post-call for ‘important’ teaching or meetings.”

- Explicit pressure to falsify duty hour logs (“If you log that, we’ll get in trouble.”)

- No system for back-up when someone is sick or on leave.

Peds-psych example: During a child psychiatry rotation, you’re told to round on pediatric inpatients early, then cover consult-liaison psych through the afternoon, and still run an evening family group therapy—frequently turning into 14–16 hour days without acknowledgment or relief.

Programs can be busy, especially in acute seasons (RSV in peds, winter psych admissions), but the difference in a malignant residency program is that leadership normalizes chronic overwork and discourages reporting.

2. Culture of Fear, Shame, or Retaliation

A toxic program often runs on fear. Residents are afraid to call in sick, to admit they don’t know something, or to ask for help.

Red flags:

- Residents mention people who “got on the PD’s bad side and never recovered.”

- Public humiliation in conferences (“grilling,” “pimping” that becomes personal).

- Retaliation after reporting concerns to GME or HR (worse schedules, poor evaluations).

- Residents whispering or looking over their shoulder when talking to you.

In pediatrics-psychiatry, this can be obscured by language about “resilience” or “toughness” in caring for complex kids and families. A malignant program may weaponize wellness rhetoric: “If you were more resilient, you wouldn’t complain about these hours.”

3. Poor Transparency and Vague Answers

If you ask direct questions and consistently get vague, evasive, or contradictory answers, treat that as a warning.

Examples:

- “How often are residents over 80 hours?”

Response: “We’re a very hardworking program; that’s what it takes to be excellent,” with no actual numbers. - “What supports exist for residents struggling with mental health?”

Response: “We’re like a family; we take care of each other,” without describing concrete systems.

For pediatrics-psychiatry, pay particular attention to:

- “How do you handle cross-cover?”

- “What happens when there are disagreements between peds and psych leadership about our duties?”

If no one can answer clearly, the structure may be chaotic—and chaos is a major driver of malignant experiences.

Specialty-Specific Risks in Pediatrics-Psychiatry and Triple Board

For a DO graduate interested in peds psych residency or triple board training, you’re entering a niche intersection between pediatrics and psychiatry. This creates unique structures that can either be beautifully integrated or dangerously fragmented.

1. Confusing Identity and Ownership

Strong programs articulate a clear identity for their combined or triple board residents. Malignant or poorly organized programs often don’t.

Questions to explore:

- “Who is ultimately responsible for us—peds PD, psych PD, or a separate triple board PD?”

- “Who completes our semi-annual evaluations and CCC reviews?”

- “Is there a dedicated combined or triple board program director with protected time?”

Red flags:

- No single person “owns” your training.

- Peds and psych leadership give conflicting expectations.

- You hear, “Honestly, we’re still figuring out what to do with triple board residents.”

This matters for your learning, but also for protection. In a malignant environment, being everyone’s resident and no one’s responsibility leaves you vulnerable to exploitation across services.

2. Imbalanced Rotations and Service Creep

In well-run osteopathic residency match programs for peds-psych/triple board, the curricular plan is respected. In malignant programs, “service creep” slowly erodes that plan.

Indicators:

- You are officially on child psychiatry, but constantly pulled to cover pediatrics ED or ward “because the team is short.”

- Combined residents are routinely used as floaters to plug holes in schedules.

- Required peds or psych educational experiences are cut short or skipped due to service needs.

Ask:

- “Do combined or triple board residents ever get pulled off one rotation to cover another department? How often?”

- “Is there a written policy limiting cross-coverage for combined residents?”

If residents admit that they are “always” the backup when someone calls out, consider this a serious red flag.

3. Training in High-Stakes, High-Intensity Settings Without Support

Pediatrics-psychiatry naturally includes exposure to:

- Child and adolescent inpatient psych

- PICU consults for suicide attempts, abuse, or medical trauma

- Complex neurodevelopmental and behavioral disorders

- Families with intense distress and complicated dynamics

This is part of the work—but malignant programs throw you into these environments without:

- Appropriate supervision (e.g., alone on child psych unit overnight as an intern)

- Backup coverage when things escalate

- Debriefing after difficult cases or deaths

- Reasonable caps on patient loads

Ask:

- “What is the maximum number of patients I’d carry on a child inpatient psych rotation?”

- “When I’m on pediatrics nights and consulted for psych issues, who backs me up?”

- “Do we have structured debriefing after sentinel events (child death, code, severe abuse case)?”

If the answer is essentially “You figure it out—this is how you get strong,” it may signal a malignant culture disguised as toughness.

DO-Specific Concerns: Subtle and Overt Bias

As a DO graduate, you may be entering a historically MD-dominated environment. Many programs are equitable and welcoming, but in a malignant residency program, DO bias can be another layer of toxicity.

1. Explicit or Implicit Devaluation of DO Training

During interviews or resident Q&A, listen for comments that suggest your DO background is “less than.”

Red flags:

- “We’ve never had a DO triple board resident before, but we’re willing to try it.”

- “Our DOs usually have to do a bit more studying to ‘catch up.’”

- Casual jokes equating DO curriculum with being “less rigorous.”

Subtle DO bias may not make a program malignant by itself, but combined with other residency red flags, it can severely affect your training experience and evaluations.

2. Barriers to Competitive Fellowships or Academic Careers

If you’re interested in child psychiatry fellowships, developmental-behavioral peds, or academic roles, the program’s attitude toward DO residents matters.

Ask:

- “What percentage of your DO graduates match into competitive fellowships?”

- “Are there any differences in research or letter-writing support for DO vs MD residents?”

- “Have DO graduates successfully pursued academic careers from your program?”

A malignant or biased program may:

- Steer DOs away from competitive fellowships (“Maybe aim lower to be safe.”)

- Undermine DO residents in subtle ways in CCC or summative letters.

If answers are vague or dismissive, be cautious.

Practical Strategies to Spot Malignant Programs Before You Match

You have limited time and data before ranking programs. Here’s how to systematically evaluate for toxic program signs during your osteopathic residency match process.

1. Read Between the Lines on Interview Day

You’re not just interviewing for any pediatrics-psychiatry or triple board slot; you’re screening programs for safety and educational quality.

Questions to ask residents (preferably when faculty are not present):

- “On your toughest rotations, what does a typical week of hours look like?”

- “When someone is struggling (academically or emotionally), how does the program respond?”

- “Have duty hour or wellness concerns ever been brought up to leadership? What happened?”

- “Have residents left the program in the last 3–5 years? Why?”

Red flags in their responses:

- Long pauses, nervous glances, “We can talk about that offline.”

- Overly rehearsed positive answers that feel scripted.

- Residents describing their experience only in terms of survival (“You just have to get through intern year; it gets better.”)

Questions specific to combined/triple board:

- “How does the program protect your educational time when service demands conflict?”

- “Have you ever felt pulled between peds and psych expectations? How was it handled?”

Look for concrete examples, not just “We communicate a lot.”

2. Analyze Program Structure and Documentation

On the program website and in interview materials, review:

- Block schedules: Are peds and psych rotations balanced as advertised?

- Policies: Are there clear, written policies on duty hours, moonlighting, supervision, and leave?

- Triple board governance: Is there a combined or triple board program director? A dedicated track coordinator?

A poorly documented, constantly “in flux” curriculum can signal deeper dysfunction. Flexibility is fine; lack of structure is not.

3. Use External Data—But Interpret Carefully

Tools and data points:

- NRMP, FREIDA, and ACGME program data

- Board pass rates (peds and psych)

- Attrition rates

- Online forums (e.g., Reddit, SDN) and alumni networks

Patterns to examine:

- High attrition (multiple residents leaving or switching programs)

- Repeated probation or ACGME citations, especially around duty hours, supervision, or mistreatment

- Significant drops in board pass rates without clear explanation

Online reports about “malignant residency program” reputations should be taken with caution, but if multiple independent sources consistently describe similar problems (e.g., bullying PD, chronic hours violations), it’s worth paying attention.

4. Trust Your Direct Impressions

Your gut reaction matters. While you should ground decisions in evidence, don’t ignore:

- Feeling dismissed or talked over when you ask substantive questions.

- Leaders making disparaging remarks about residents, other programs, or DO schools.

- An atmosphere of fear or exhaustion you can’t quite articulate—residents avoiding eye contact, joking bitterly about patient safety, or warning you off certain rotations in hushed tones.

You’ll be spending years of your life in this environment. If something feels deeply wrong, treat that as meaningful data.

Protecting Yourself If You Land in a Toxic or Malignant Program

Despite careful screening, some DO graduates still end up in a malignant pediatrics-psychiatry or triple board residency. If that happens, there are steps you can take.

1. Document Objectively

Keep:

- A private, secure log of duty hour violations (dates, shifts, duration).

- Specific incidents of mistreatment, bullying, or unsafe practices:

- Date, time, location

- People involved

- What was said/done

- Impact on patient care or resident safety

Objective documentation is essential if you need to:

- Request support or remediation

- Report conditions to GME, ACGME, or HR

- Explore transfer to another program

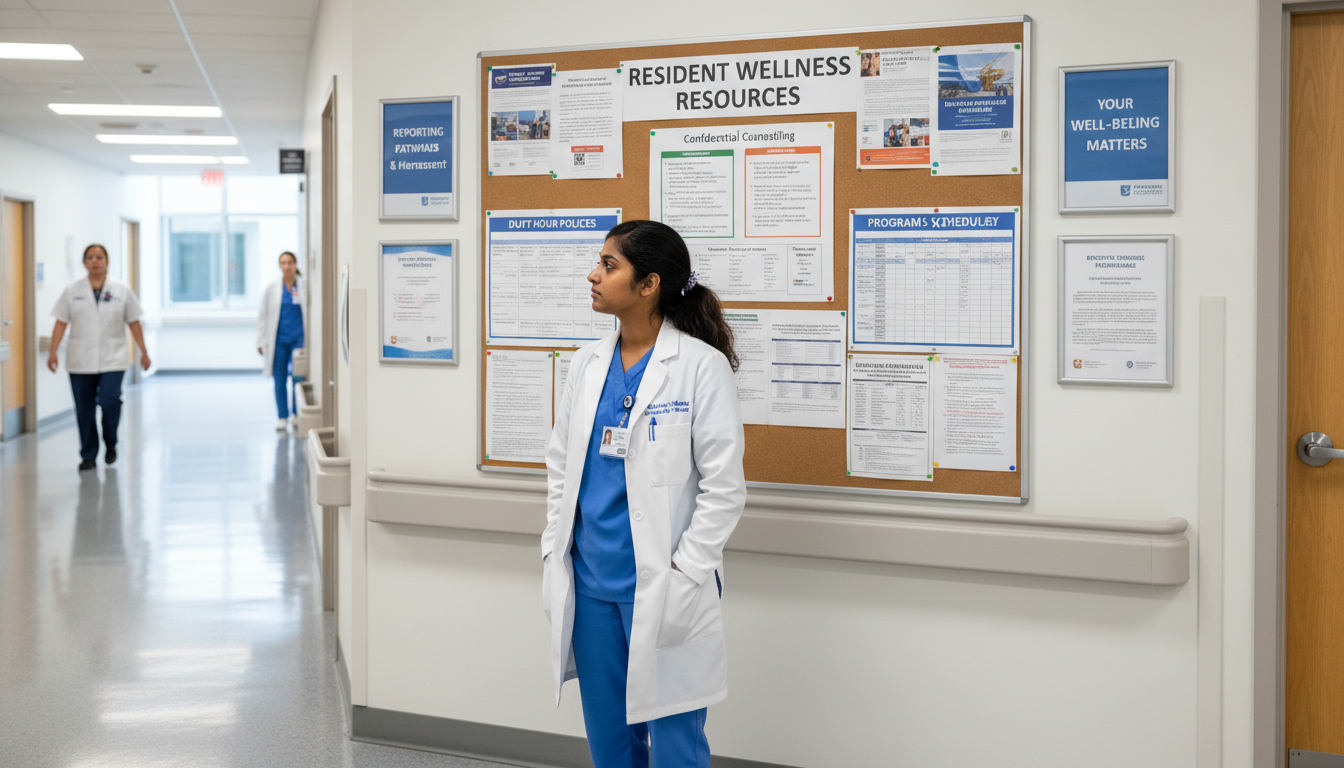

2. Use Internal Support Channels

Options usually include:

- Program director or associate PD (if safe)

- Chief residents

- Designated institutional official (DIO)

- GME office and anonymous reporting systems

- Employee assistance programs (EAP) and mental health services

When describing issues, frame them around patient safety and educational impact, not just personal dissatisfaction. For example:

- “Repeated 28–30 hour shifts without rest are causing cognitive errors on rounds and during admissions.”

- “I’m not receiving required supervision on high-risk child psych consults, which I believe endangers patients and my ability to train safely.”

3. Seek External Mentorship

Especially as a DO graduate, connecting with mentors outside your institution is crucial:

- DO faculty from your medical school who trained in peds, psych, or triple board

- Alumni from your med school now in similar specialties

- National organizations:

- AAP Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics

- AACAP (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry)

- AOA and specialty DO societies

External mentors can:

- Validate whether what you’re experiencing is actually malignant vs “normal hard”

- Advise on navigating internal politics

- Help you explore transfer options or alternative paths

4. Consider Transfer If Necessary

Leaving a program is a serious decision, but staying in a malignant residency program that jeopardizes your health and training can be worse.

If you’re considering transfer:

- Talk confidentially with trusted mentors and your medical school’s dean or advisor.

- Gather your evaluations, procedure logs, and documentation of issues.

- Research other pediatrics-psychiatry or triple board options—but also be open to pivoting (e.g., categorical peds or psych) if that protects your long-term career and well-being.

Remember: completing training in a healthy environment is more important than forcing yourself to stay in a toxic combined track at all costs.

Balancing Ambition with Safety in Your Rank List

When finalizing your rank list as a DO graduate targeting peds psych residency or triple board, you’ll juggle multiple priorities:

- Prestige and academic reputation

- Fellowship and career prospects

- Geographic preferences

- Fit with combined training structure

- Culture and wellness

Here’s a simple principle: Do not rank a program you would not be willing to attend. No “reach” is worth serious psychological harm.

A reasonable approach:

- Eliminate clearly malignant or high-risk programs from your list, even if they’re prestigious.

- Prioritize programs with strong culture and clear structure over name recognition alone.

- Consider DO-friendliness as a real factor, especially if you’re interested in academic or subspecialty paths.

- Use your rank list to maximize safety and support first, then optimize for prestige, research, or location.

Residency is finite; your health and career are not. A supportive, non-toxic program will almost always position you better for the long term, whether in child psychiatry, developmental-behavioral pediatrics, or other subspecialties.

FAQs: Malignant Programs in Pediatrics-Psychiatry for DO Graduates

1. How can I tell if a program is “just busy” versus truly malignant?

Busy programs:

- Are upfront about heavy workloads and high patient volumes.

- Have systems to back you up when you’re overwhelmed.

- Encourage honest duty hour reporting and adjust schedules as needed.

- Provide emotional and educational support, even when work is intense.

Malignant programs:

- Normalize chronic overwork and pressure you to under-report hours.

- Respond to concerns with blame or dismissal (“Everyone else can handle it.”).

- Leave you unsupported on high-stakes rotations (e.g., child psych nights, PICU consults).

- Have a pervasive culture of fear, shaming, or retaliation.

The more you see patterns across multiple domains (hours, culture, supervision, leadership), the more likely it’s malignant rather than simply busy.

2. Are smaller pediatrics-psychiatry or triple board programs more likely to be malignant?

Not inherently. Smaller programs can actually be highly supportive and personalized. However, small size carries risks:

- Less redundancy: One toxic leader or senior resident impacts everyone.

- Fewer peers: If you clash with the culture, you may feel isolated.

- Less oversight: Problems may go unnoticed by external bodies longer.

To assess a small program, ask specifically about:

- How conflicts are handled when personalities clash.

- Attrition history (“Has anyone ever left the program?”).

- How leadership ensures resident wellness and safety with limited numbers.

3. As a DO graduate, should I avoid programs that have never taken DO residents before?

Not necessarily—but proceed carefully. A program that has not historically matched DOs can still be excellent and inclusive. Key is how they talk about it:

Positive signs:

- “We haven’t had a DO resident yet, but we’ve actively recruited DO applicants and value osteopathic training.”

- Faculty aware of COMLEX/USMLE equivalencies and DO curriculum.

- Genuine curiosity and respect for your background.

Red flags:

- Surprised comments about your degree (“Oh right, you’re a DO. Do you still do that manipulative stuff?” in a dismissive tone.)

- Ignorance about COMLEX or DO accreditation.

- Statements implying DOs are “a backup plan” for them.

If they’ve never had DOs and you sense bias or reluctance, consider ranking them cautiously or not at all if other concerns are present.

4. What if my dream triple board program shows some red flags but also amazing opportunities?

Few programs are perfect. You may encounter minor concerns even in excellent institutions. Weigh:

- Severity and scope of red flags (one concerning attending vs entire leadership culture).

- Pattern over time (isolated complaint vs repeated reports across years).

- Your personal resilience and support network (will you have mentors, family, or peers to buffer stress?).

If the red flags involve systemic mistreatment, chronic hours violations, or DO bias, treat them seriously—even if research or fellowship opportunities are outstanding. You can often find excellent training and academic pathways in healthier environments; recovering from a malignant program is much harder.

Choosing a pediatrics-psychiatry or triple board residency as a DO graduate is a bold and meaningful path. By recognizing residency red flags, understanding what constitutes a malignant residency program, and trusting both your research and your instincts, you can protect your well-being while building the career you want.