Understanding Research During Residency as a US Citizen IMG in General Surgery

For a US citizen IMG (American studying abroad), research during residency in general surgery is not just an optional enrichment activity—it is often a key factor that shapes your career trajectory, opens doors in competitive fellowships, and helps you stand out in an increasingly academic and data‑driven specialty.

General surgery has a long-standing culture of inquiry: quality improvement initiatives, outcomes research, translational science, and clinical trials all play a central role in advancing patient care. As a resident, you’re at the intersection of clinical practice and academic innovation, which makes residency an ideal time to build your research identity—even if you did not have extensive research experience in medical school.

This article will walk you through:

- Why research during residency matters—especially for a US citizen IMG

- The different forms research can take in general surgery

- How to choose an academic residency track and program culture that fits your goals

- Practical strategies to get started and stay productive as a busy trainee

- How to convert resident research projects into long-term career capital

Throughout, the focus will be on the specific challenges and opportunities faced by an American studying abroad who is now training in the US system.

Why Research During General Surgery Residency Matters for US Citizen IMGs

Standing Out in a Competitive Field

General surgery remains highly competitive, and many residents will eventually pursue fellowships (e.g., surgical oncology, cardiothoracic surgery, minimally invasive surgery, trauma/critical care, colorectal). Fellowship program directors pay close attention to:

- Peer-reviewed publications

- Conference presentations

- Research productivity during residency

- Evidence of sustained academic interest

As a US citizen IMG, you may already feel you had to “prove yourself” to secure a general surgery residency match. Research during residency is a powerful equalizer:

- It demonstrates you can thrive in the same academic environment as US MD/DO graduates.

- It helps to counter any lingering bias about training abroad by showcasing objective academic output.

- It builds a track record that is visible on your CV, ERAS applications for fellowship, and in letters of recommendation.

Strengthening Your Professional Identity

Research is a way to define your niche as a surgeon. During residency you are exposed to:

- Various subspecialties (hepatobiliary, surgical oncology, vascular, trauma, transplant, etc.)

- Diverse patient populations

- Evolving technologies and techniques

Through research, you can begin to answer questions such as:

- Am I drawn to outcomes research (e.g., readmissions, complications, health disparities)?

- Do I enjoy basic or translational lab work (e.g., molecular pathways in cancer)?

- Am I passionate about education research (e.g., simulation, resident performance, wellness)?

- Do I want to focus on quality improvement and systems-based practice?

As an American studying abroad who returns to the US for training, you may bring a unique perspective: global surgery, differences in health systems, and cross-cultural patient care. These can become themes in your resident research projects.

Enhancing Career Flexibility and Leadership Potential

Surgeons who engage in research during residency often:

- Have more options for academic faculty positions after fellowship

- Are competitive for leadership roles (program director, division chief, quality officer)

- Develop skills in data analysis, critical appraisal, and project management that are valuable regardless of practice setting

Even if you plan on a primarily clinical career, early exposure to research helps you critically interpret literature and incorporate evidence-based practices into your operative and perioperative decision-making.

Types of Research Opportunities in General Surgery Residency

Research during residency in general surgery is far broader than “basic science in a lab.” Understanding the spectrum of options will help you choose opportunities that fit your interests, skills, and schedule.

1. Clinical Outcomes Research

This is often the most accessible form of research for residents:

- Uses patient data from electronic medical records, national databases (e.g., NSQIP, NCDB), or institutional registries

- Explores questions like:

- What factors predict postoperative complications in emergency laparotomy?

- Are there disparities in time-to-surgery for colon cancer based on insurance status?

- How do enhanced recovery pathways affect length of stay and readmission?

Why it’s great for US citizen IMGs:

- Can often be started without prior lab experience

- Allows flexible involvement alongside clinical duties

- Builds skills in data analysis and statistics, which are valued in academic surgery

2. Quality Improvement (QI) and Patient Safety Projects

QI projects are often embedded in residency curricula and can double as research if designed rigorously:

- Examples:

- Implementing a new VTE prophylaxis protocol and measuring its impact

- Reducing central line infections in the surgical ICU

- Optimizing pre-op antibiotic timing in emergent cases

Key point: Many QI projects can yield publishable abstracts or manuscripts if you:

- Define clear outcomes

- Use pre- and post-intervention data

- Collaborate with a methodologist or QI expert

For an American studying abroad, QI research can highlight your commitment to systems improvement and patient safety—attributes programs and employers value highly.

3. Basic and Translational Science

Some general surgery departments maintain robust basic science or translational labs (e.g., cancer biology, immunology, tissue engineering). Projects might include:

- Investigating molecular markers for tumor aggressiveness

- Developing animal models of ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Studying biomaterials for hernia repair

Characteristics:

- Typically requires dedicated research time (1–3 “lab years” between PGY-2 and PGY-3/4)

- Produces high-impact, mechanistic insights

- Particularly valuable if you are aiming for a heavily academic residency track and long-term NIH-funded career

As a US citizen IMG, gaining entry into such labs may require:

- Early communication with research faculty

- Clear demonstration of commitment

- Possibly prior lab experience (though motivated beginners can also be trained)

4. Education and Simulation Research

General surgery residencies increasingly emphasize:

- Technical skills simulation

- Competency-based assessment

- Wellness and burnout prevention

- Diversity, equity, and inclusion in training

Resident projects might include:

- Evaluating a laparoscopic simulation curriculum

- Studying the impact of a new handoff system on resident satisfaction and error rates

- Assessing interventions for reducing burnout among surgical trainees

These projects are often feasible during clinical years and may resonate especially with residents who enjoy teaching, leadership, or medical education.

5. Global and Health Services Research

As a US citizen IMG, you may have first-hand experience with healthcare systems outside the US. This can lead to:

- Comparative studies of surgical care (e.g., resource use, outcomes)

- Projects in global surgery access and capacity

- Collaborations with institutions abroad on specific disease burdens

Health services research areas include:

- Cost-effectiveness analysis

- Access to emergency general surgery care

- Telemedicine in perioperative care

These fields are increasingly visible in high-impact journals and can merge your international background with a US academic career.

Choosing an Academic Residency Track and Program Culture

Academic vs. Community-Focused Residency Programs

Not all general surgery residencies are equally research-oriented. When you’re evaluating programs (even if you’ve already matched, this can guide how you navigate where you are):

Highly academic programs typically:

- Are university-based or major academic centers

- Offer formal research tracks or mandatory research years

- Have numerous faculty with active grants and lab space

- Expect residents to present at national meetings and publish

Community-focused or hybrid programs often:

- Have less protected research time during clinical years

- Focus more on operative volume and hands-on experience

- Still offer access to QI, clinical, and education research—but with fewer formal structures

As a US citizen IMG, your strategy should balance:

- Your long-term goals (academic vs. community practice vs. mixed)

- The kind of environment where you thrive (high-pressure academic vs. smaller, hands-on)

- The resources realistically available for research at your program

Academic Residency Track: What It Means

An “academic residency track” in general surgery may include:

- Dedicated research years (often 1–3 years) between junior and senior residency

- Formal mentoring structures for research

- Coursework in biostatistics, epidemiology, or clinical trial design

- Expectations to produce multiple first-author publications

If you aspire to:

- A competitive fellowship (surgical oncology, CT surgery, transplant, etc.)

- A faculty position at an academic center

- Pursuing an MPH, MS, or PhD during or after residency

…then an academic track can be especially advantageous.

For an American studying abroad, joining an academic track can:

- Solidify your reputation as a serious academic surgeon

- Offer time to fill in research gaps from medical school

- Provide structured mentorship that might not have been available previously

Questions to Ask About Research Culture

Even if you are already in residency, you can assess and optimize your environment. Helpful questions include:

- How many residents present at national/regional meetings each year?

- How many peer-reviewed publications do graduates typically have?

- Are there required or optional research blocks?

- Do residents have access to statisticians, methodologists, or a clinical research office?

- Are research mentors proactive and approachable?

Red flags:

- No clear point person for resident research

- Minimal record of resident publications

- “You can research if you find time” but no structural support

If your program is light on formal structures, you can still build a strong research portfolio—but you’ll need to be more proactive and strategic.

Getting Started: Practical Steps for Busy Surgery Residents

Step 1: Clarify Your Goals Early

As a PGY-1 or early PGY-2, ask yourself:

- Do I want to pursue a highly academic career, a primarily clinical practice, or something in between?

- Am I considering research-intensive fellowships (e.g., surgical oncology, CT surgery)?

- How comfortable am I with statistics, study design, and scientific writing?

Your answers will influence:

- How aggressively you seek research mentors

- Whether you push for dedicated research time

- Which types of projects you prioritize

Step 2: Find the Right Mentor(s)

A strong mentor is more important than the perfect topic. Look for faculty who are:

- Productive: They publish regularly and present at meetings.

- Accessible: They respond to emails, meet with you, and integrate residents into their projects.

- Supportive: They understand the challenges of residency schedules and IMG transitions.

As a US citizen IMG, you may also benefit from:

- Mentors who have worked with IMGs or international trainees before

- Faculty who can advocate for you in letters and departmental discussions

- Peer mentors (senior residents) who have successfully completed projects

Actionable tips:

- Attend departmental research conferences, journal clubs, and M&M.

- Email 2–3 potential mentors with:

- A concise introduction (including IMG background and career goals)

- A brief CV

- A statement of your interest in research and time you can realistically devote

- Ask senior residents which attendings are truly engaged in resident research.

Step 3: Start Small and Finish Something

Early wins matter. Rather than waiting for a perfect, large-scale project:

Start with projects that have a short timeline, such as:

- Case reports or case series (especially rare or instructive cases)

- Retrospective chart reviews on a focused question

- QI projects that are already in motion (e.g., a bundle for postoperative care)

Your priorities:

- Get on a project where you can be first or second author.

- Aim to complete at least one abstract or poster for a regional or national meeting within your first 1–2 years.

- Learn the full pipeline: IRB → data collection → analysis → abstract → presentation → manuscript.

For an American studying abroad who may feel pressure to “catch up,” a completed, presented, and published project—even a modest one—carries more weight than multiple half-finished ambitious projects.

Step 4: Learn the Basics of Study Design and Data

You do not need a PhD in biostatistics to be a productive resident researcher, but you should:

- Understand common study designs:

- Retrospective cohort, case-control, cross-sectional

- Prospective observational

- Randomized controlled trials (as a participant or coordinator)

- Know basic statistical concepts:

- P-values, confidence intervals, odds ratios, hazard ratios

- Common tests (Chi-square, t-test, logistic regression)

Practical strategies:

- Take advantage of institutional workshops or online modules in research methods.

- Use free/low-cost resources:

- Coursera/edX courses on biostatistics and epidemiology

- Tutorials from surgical societies (e.g., ACS, SAGES)

- Ask your mentor to connect you with a statistician early in the project planning.

Step 5: Plan Research Around Your Schedule

General surgery residency is demanding. To integrate research during residency effectively:

- Use micro-scheduling:

- 20–30 minutes after sign-out to edit a manuscript section

- Early morning on a lighter day to clean a dataset

- Leverage “burst” productivity:

- On elective rotations or lighter call months, plan concentrated research pushes.

- Protect your off days:

- Dedicate a portion (e.g., half-day) periodically to research tasks.

- Communicate boundaries to avoid constant interruptions.

Tools that help:

- Reference managers (Zotero, Mendeley, EndNote)

- Task managers (Trello, Notion, Asana) for project tracking

- Shared cloud folders with your mentor and co-authors

Remember: consistency over perfection. Small, regular progress adds up to completed projects.

Maximizing the Impact of Resident Research Projects

Turning Projects into Presentations and Publications

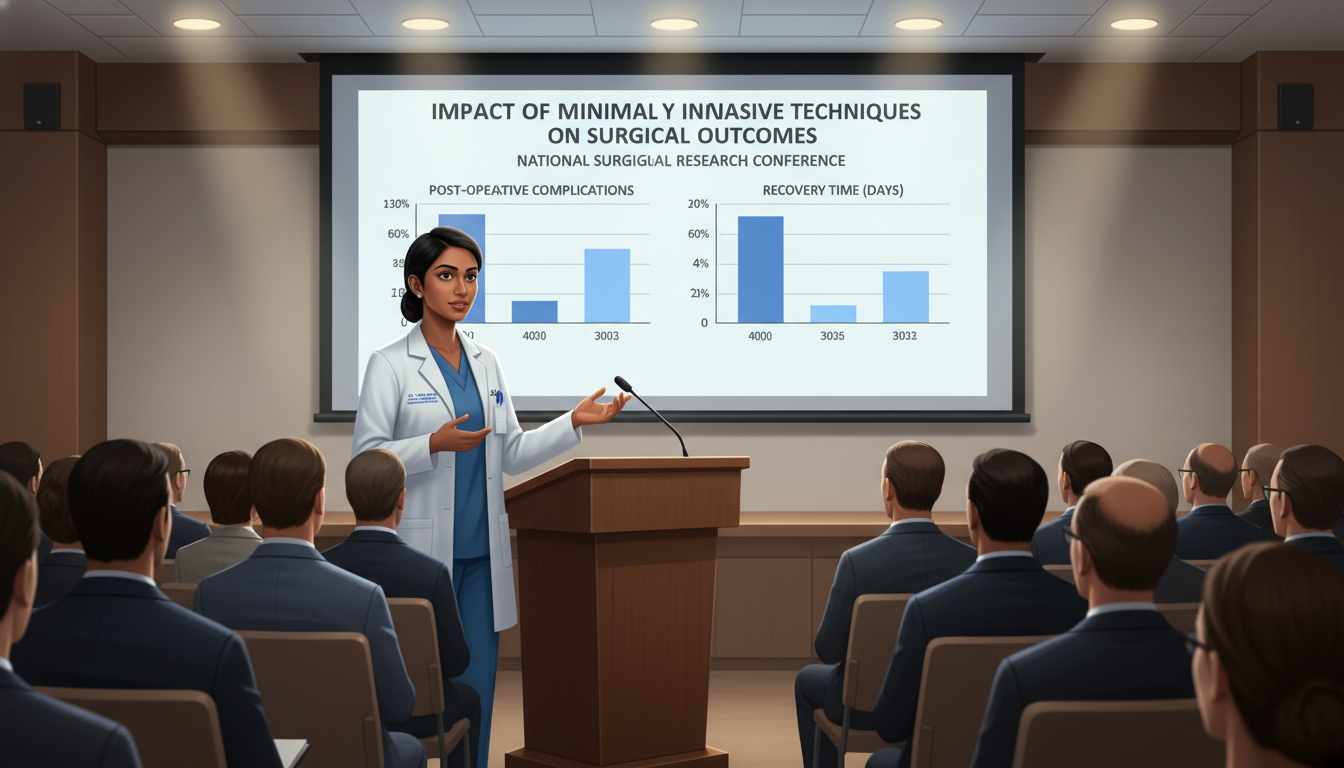

Aim to present your work at:

- Institutional research days

- Regional society meetings

- National conferences (e.g., ACS, SAGES, AAS, APSA, EAST, SSAT)

Benefits:

- Networking with potential fellowship directors and collaborators

- Feedback that strengthens your manuscript

- Visible evidence of your academic involvement on your CV

For publications:

- Aim for peer-reviewed journals appropriate to your topic and scope.

- Consider surgical specialty journals (e.g., JAMA Surgery, Annals of Surgery, Surgery, Journal of Surgical Research) as aspirational targets, but be realistic based on your study’s strength.

- Don’t let perfect be the enemy of done—an honest, carefully written paper in a solid journal is better than a never-submitted “ideal” project.

Building a Coherent Academic Narrative

Over the course of residency, try to develop some thematic continuity. For example:

- Trauma/acute care surgery:

- Outcomes of emergency laparotomy

- QI project on time-to-OR for trauma patients

- Education research on trauma simulation training

- Surgical oncology:

- Database studies on disparities in cancer care

- Lab work on tumor biology during research years

- QI project on multidisciplinary tumor boards

As a US citizen IMG, you might integrate:

- Global surgery or international comparisons

- Health services research focusing on access and equity

- Methodological strengths in data analysis or systematic reviews

When you apply for fellowships or early faculty positions, you can articulate a clear, cohesive story:

“I began by examining outcomes in [area]. Over time, I developed a focus on [specific niche], which I explored through [clinical outcomes/QI/basic research]. Going forward, I plan to build an academic career centered on [focused theme].”

Using Research to Strengthen Your Professional Network

Your research during residency can connect you with:

- Faculty within your institution

- Researchers at other centers (co-authored projects, multi-institutional collaborations)

- Leaders in your field met at conferences

Practical networking tips:

- When presenting, introduce yourself to session moderators and other presenters.

- Email researchers whose work you admire, referencing specific papers and asking brief, focused questions.

- Consider joining trainee sections of surgical societies, many of which offer:

- Abstract awards

- Travel grants

- Mentorship programs for residents (including IMGs specifically in some organizations)

For an American studying abroad, this networking can offset any initial disadvantage from having gone to medical school overseas, by letting people judge you on your current work and potential.

Integrating Research During Dedicated “Lab Years”

If you choose or are in an academic residency track with dedicated research years:

Use that time strategically:

- Define specific output goals at the start:

- Number of first-author papers

- Grants or small pilot funding applications

- Skills to acquire (e.g., advanced statistics, animal surgery techniques)

- Consider additional formal training:

- MPH or MS in Clinical Investigation

- Biostatistics or data science coursework

- Maintain some clinical exposure:

- PRN shifts in the OR or ICU (if your program allows)

- Participation in conferences and M&M

As a US citizen IMG, lab years can be a powerful “accelerator” for:

- Building a substantial publication record

- Competing effectively for top fellowships

- Transitioning from “IMG” in people’s minds to “serious academic surgeon”

Just ensure you don’t become disconnected from clinical surgery; balance is key.

Common Challenges for US Citizen IMGs—and How to Overcome Them

Challenge 1: Limited Prior Research Experience

Many IMGs train at schools where structured research is less common or less emphasized. To counter this:

- Be honest with mentors about your starting point.

- Offer high motivation and reliability in exchange for initial guidance.

- Start with well-defined tasks:

- Literature reviews

- Data entry and cleaning

- Drafting introductions and methods sections

You can quickly build skills and academic credibility through consistent follow-through.

Challenge 2: Time Pressure and Burnout Risk

Surgery residency is intense, and adding research can feel overwhelming.

Strategies:

- Choose a realistic number of active projects (e.g., 1–2 main projects, 1 smaller side project).

- Set micro-goals:

- “This week: finalize IRB draft”

- “This weekend: analyze preliminary data with mentor”

- Protect sleep and mental health; chronic burnout undermines both clinical and academic performance.

Challenge 3: Navigating Cultural and System Transitions

Even as a US citizen, you may experience “re-entry shock” coming from an international school:

- Different documentation styles

- Different research ethics and IRB norms

- New expectations for communication and hierarchy

Solutions:

- Observe how senior residents interact with faculty and research staff.

- Ask peers to review your emails or drafts for tone and format, especially early on.

- Attend institutional orientations or workshops on research ethics and compliance.

Your international background is an asset; you’re simply adapting it to a new environment.

Challenge 4: Undersupported or Non-Academic Programs

If your residency program has limited formal research infrastructure:

- Look for:

- Hospital quality improvement departments

- Institutional review board staff who can guide your proposals

- Non-surgical departments (e.g., anesthesia, ICU, oncology) open to collaboration

- Consider multi-institutional or database projects led by national societies.

- Use online tools and remote mentorship, even from outside institutions, with your program’s approval.

While an academic residency track offers advantages, meaningful research is still possible in more clinically focused settings with initiative and creativity.

FAQs: Research During Residency for US Citizen IMG in General Surgery

1. I’m a US citizen IMG just starting general surgery residency. How soon should I get involved in research?

You should begin exploring research during your PGY-1 year, even if only by:

- Attending research meetings and journal clubs

- Meeting potential mentors

- Helping on small, contained tasks (literature review, data entry)

Aim to have at least one clearly defined project by late PGY-1 or early PGY-2. The earlier you start, the more time you have to complete projects and build a portfolio.

2. Do I need basic science research to be competitive for academic surgery or fellowships?

Not necessarily. Many successful academic surgeons build careers on:

- Clinical outcomes research

- Quality improvement and patient safety

- Health services and disparities research

- Education and simulation research

Basic or translational lab work is particularly valuable if you want a heavily research-focused career (e.g., NIH-funded investigator), but it is not mandatory for all academic or fellowship paths. What matters most is consistent, high-quality output and a coherent academic narrative.

3. How many publications should I aim for by the end of residency?

There is no universal “magic number,” but general benchmarks:

- For a resident interested in community practice:

- A handful of publications (e.g., 2–5), including some first-author work, is often sufficient.

- For those targeting competitive fellowships or academic careers:

- More robust productivity (e.g., 8–15 publications, several as first author) is common, especially if you have 1–2 dedicated research years.

Remember: quality and relevance of work, strength of mentorship, and letters of recommendation matter as much as raw numbers.

4. Can I still build a strong research profile if my general surgery residency program isn’t very academic?

Yes—though it requires more initiative. You can:

- Focus on QI and patient safety projects that directly improve local care

- Leverage institutional or national databases for clinical outcomes studies

- Seek mentors in other departments or at affiliated academic centers

- Participate in multi-center or society-led projects

As a US citizen IMG, demonstrating that you created opportunities in a less structured environment can be a powerful story of resilience, leadership, and self-direction.

By approaching research during residency thoughtfully—selecting good mentors, starting early, choosing feasible projects, and aligning your work with your long-term goals—you can transform your years as a general surgery resident into a foundation for a fulfilling, impactful career. As an American studying abroad who returns to the US training system, your unique path can become an academic strength, not a liability, when you use research as a tool to define and elevate your role in the surgical community.