It’s 11:47 p.m. You’re on PubMed again, doom‑scrolling through classmates’ names popping up as first authors in journals you actually recognize. Someone from your year just posted their JAMA Surgery paper on Instagram. Another has “4 first‑author manuscripts (3 accepted, 1 under review)” on their CV… and you are still stuck in a Word document titled “Draft_v3_final_REALfinal_EDITED.”

You’re not lazy. You’re not clueless. You’ve gone to the “how to get involved in research” workshops, politely emailed faculty, maybe even joined a project. Yet nothing seems to make it across the finish line with your name in that first slot.

Let me tell you what really happens behind the scenes and why some students keep stacking first‑author papers while you’re still “data collection in progress.”

It’s not about who’s smartest.

It’s about who understands the unspoken rules of academic medicine.

Let’s walk through them.

(See also: The Unspoken Rules of Authorship Medical Students Never Hear for more details.)

The Myth You’ve Been Sold About Research

Everyone tells premeds and early med students the same cartoon version of research:

Find a mentor. Join a project. Work hard. Publish.

That’s not how it works inside the machine.

Here’s what actually happens at most academic centers:

Faculty are juggling clinic, admin, teaching, grants, and their own promotion timelines. When a student emails them, they are not thinking, “How can I help this person grow?” They are thinking, “Is this person going to make my life easier or harder?”

The students who rack up first‑author papers have understood this—explicitly or instinctively. They align themselves with:

- The right kind of projects

- The right kind of mentors

- The right invisible roles on a paper

You’re probably making one of three classic mistakes:

- You’re attached to the wrong kind of project.

- You’ve joined the wrong mentor’s ecosystem.

- You’re doing a lot of “work” that doesn’t translate into authorship power.

None of this gets said in info sessions or premed advising. Faculty don’t put this part on PowerPoint slides. But in closed‑door meetings, this is exactly how they talk about students.

The Hidden Economy of First‑Author Spots

Let’s get brutally clear: first‑author on a paper is not a trophy. It’s currency.

Program directors, research chairs, and grants committees use it as a signal. Not “this person pipetted well,” but “this person can independently drive a project from idea to publication.”

So when a PI is deciding who gets first authorship, here’s what really tips the scale—based on the conversations that happen when you are not in the room:

- Who actually moved the project from stuck → done?

- Whose name strengthens the lab’s future pipeline (loyalty and long‑term payoff)?

- Who can the PI trust to not implode under deadlines or revisions?

That’s why you see some average students with mediocre Step scores sitting on five first‑author manuscripts in orthopedics, while objectively “stronger” students have one middle‑author case report in a journal no one reads.

The key: those students made themselves invaluable in the exact stages that matter for authorship assignments.

You, on the other hand, may be stuck in the “free labor” zone.

You’re entering data, attending lab meetings, maybe consenting patients—useful work, but the kind faculty plug in as “research assistant” regardless of authorship.

The students who get first‑author learn to position themselves at the choke points of the project—the places where it literally dies without someone pushing it.

How “First‑Author Students” Actually Operate

Let’s strip away the clichés. Here’s how high‑yield students really navigate research from premed through early med school.

1. They Choose Projects That Can Actually Finish

Program directors know the pattern: the student with “3 ongoing projects” and “nothing submitted” is usually someone who picked sexy but unfinishable ideas.

Common trap projects:

- Prospective clinical trials needing 2+ years of enrollment

- Multi‑center collaborations without a strong coordinating PI

- Basic science work where the postdoc disappears and the project dissolves

- “We’re building a database” projects with no clear question defined

Meanwhile, the students who actually publish are sliding into:

- Retrospective chart reviews with existing data

- Secondary data analyses of already built registries

- Systematic or scoping reviews with defined timelines

- Short, targeted education projects or survey studies

- Single‑center clinical series the PI has done 10 times before

When you’re premed or in preclinical years, you don't need “exciting.” You need “finishable, with guardrails.”

At one large Northeast academic center, the residents can tell you exactly which cardiology attending is “the retrospective machine” who turns every student project into a manuscript within a year. Yet premeds keep flocking to the basic science star whose lab has a five‑year publication cycle.

Guess who shows up on rank lists with actual first‑author lines.

2. They Secure Authorship Expectations Upfront (Without Sounding Entitled)

Here’s something most students never do, and it costs them authorship every year.

When they join a project, they don’t ask:

- “Who’s currently planned as first author on this?”

- “What would I need to do for you to feel comfortable putting me as first author?”

- “Is that realistically possible given where the project stands now?”

Faculty respect this when it’s done right. You’re not demanding; you’re clarifying.

Behind closed doors, here’s what attendings say:

- “I had no idea the student expected first author; they came in when it was already written.”

- “If they’d told me early they wanted that role, I could’ve given them a different project.”

- “Once the fellow had already done the heavy lift, I wasn’t going to bump them.”

The students who consistently end up as first authors usually have emails like this in their archive:

“As we discussed today, I’ll take primary responsibility for drafting and revising the manuscript, and if I can carry it through to submission, I’ll be listed as first author. Please let me know if I’ve misunderstood your expectations.”

That single email becomes the paper trail everyone quietly respects when authorship questions arise.

You’re silently assuming you’ll get first author if you “do enough.” That’s how you end up third.

3. They Live in the Manuscript, Not Just in the Data

Inside departments, there’s a very specific label for the students who get things done: “They can write.”

Not “they collected a ton of data.” Not “they helped with recruitment.”

“They can write.”

Why? Because faculty know data can sit in an Excel file for three years and die. But once a student has a working draft with intro, methods, and at least a skeleton of results, it’s psychologically and practically harder for everyone to abandon it.

The students who secure first‑author positions:

- Volunteer to write the first full draft, not just “I can edit.”

- Learn how to structure a manuscript in the exact style of that field’s top journals.

- Accept brutal tracked‑changes edits from attendings without emotionally unraveling.

- Turn around revisions fast—48–72 hours, not 3 weeks.

I’ve sat in meetings where the PI says something like:

“Look, the fellow started the project, but Jamie actually wrote the whole thing and handled reviewer 2. I’m putting Jamie first.”

You want to be Jamie.

The best students build a habit early: for every project they touch, they at least outline the paper as if they’ll write it. Even if they do not end up first author, this posture puts them into the “manuscript owner” role far more often.

The Mentor Problem: You’re Loyal to the Wrong People

There are two types of “research mentors” from a student’s perspective:

- The Star Attending who looks amazing on your CV but never has time to finish anything.

- The Mid‑Level Workhorse who quietly churns out 10+ papers a year with students.

Guess which one gets you first‑author papers.

I’ve heard students brag, “I’m doing research with the Chair of Neurosurgery.” Translation in faculty language: “I have attached myself to someone chronically overcommitted who will reply to my drafts in 4–6 months, if ever.”

You need to start evaluating mentors like an insider:

- Do they have multiple student first‑authors on PubMed in the last 2–3 years?

- Is there a senior resident/fellow in their orbit who actually drives projects?

- Are their papers mostly case reports, or do they publish full original research with learners?

- When you show them work, do they respond within 1–2 weeks or vanish?

One ENT department chair I know tells residents bluntly: “If a student attaches to Dr. X, they’ll get big‑name letters and nice conferences. If they attach to Dr. Y, they’ll get four co‑authors. If they attach to Dr. Z, they’ll get two first–authors by the time they apply.”

Students who do not understand this difference end up loyal to prestige instead of productivity.

The students who do understand quietly migrate toward the Zs of the department.

The Timeline Trap: Why Your Hard Work Never Matures Into a Paper

From the outside, it looks like some students are just lucky: all their projects magically become manuscripts by ERAS season.

From the inside, the story is uglier and more disciplined.

Here’s the unspoken truth: most student projects die in two windows.

- Death Window #1: After data collection, before first full draft

- Death Window #2: After first rejection, before resubmission

Faculty talk about this all the time:

“We have 6 complete datasets from last year and no papers because the students disappeared or never wrote.”

“Once the journal rejected it, the student just lost steam and moved on.”

The students who rack up first‑authors do something different:

They treat a project as alive until it is either (1) published, or (2) explicitly buried.

Which means:

- They keep a personal timeline: “By March 1, full draft. By April 1, co‑author edits back. By May 1, submitted.”

- When the paper gets rejected, they email within days: “Can we target X journal next? I can reformat the manuscript this week.”

- They don’t quietly vanish when clerkships get busy; they send an honest update and a new plan.

There is a GI fellow I know who gives students a simple warning: “If you disappear on one project, you’re done with me.” The students who hear that and still stick around? They’re the ones who apply with three first‑author GI papers in two years.

You’re probably underestimating how much faculty value persistence over brilliance.

They will forgive mediocre stats skills; they will not forgive abandonment.

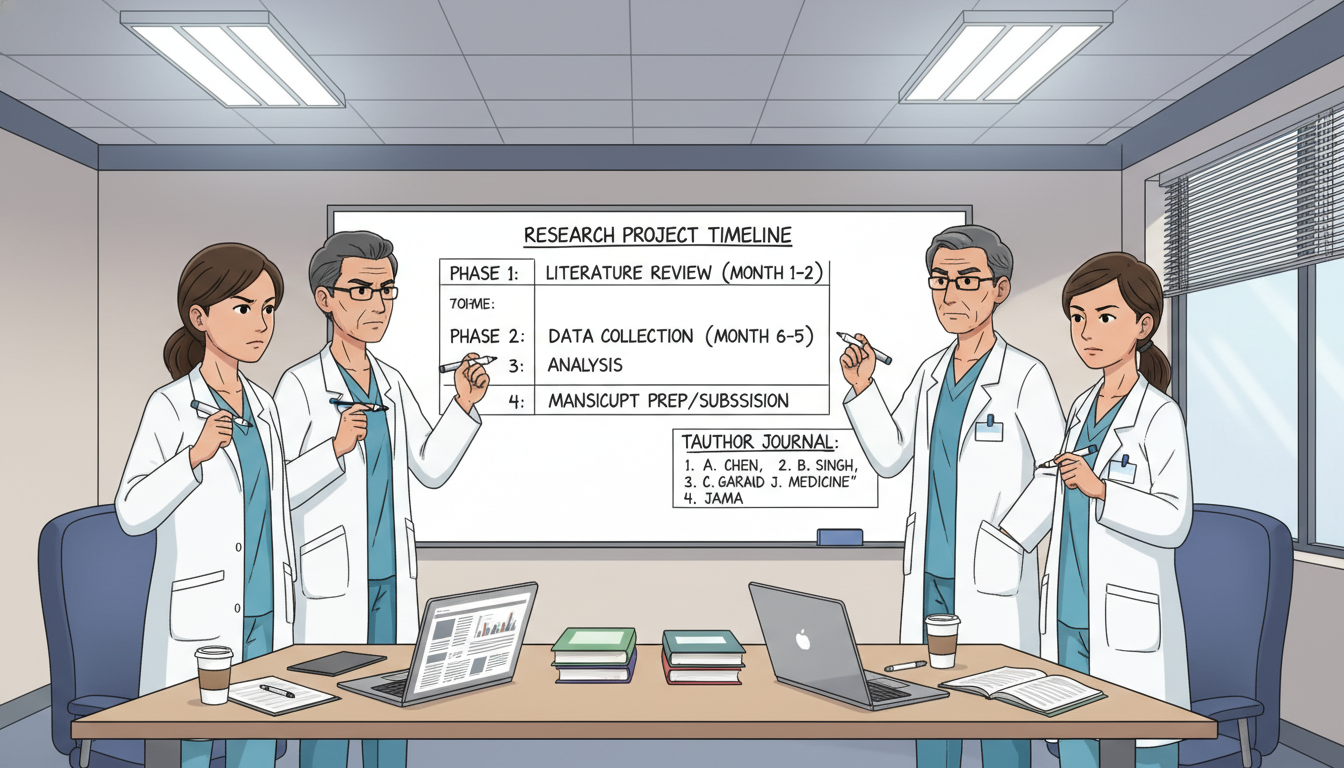

The Politics of Author Order That No One Explains

Let’s talk about the reality almost never said out loud.

When it’s time to assign authorship, faculty are quietly balancing:

- Hierarchy: residents, fellows, other faculty in the mix

- History: who’s been loyal to the lab over time

- Risk: who will need this paper urgently for residency or fellowship

This is why you sometimes see something like:

- Fellow as first author

- Student as second

- Resident buried in the middle somewhere

Even if the student worked more than the fellow.

From multiple departments, here’s what I’ve heard behind closed doors:

- “The fellow needs this for their GI application in six months; the student is an M2.”

- “We promised the resident a first‑author before graduation; can the student take second?”

- “This student has three other papers; this resident has zero.”

That sounds unfair. It is. But it’s how authorship politics works when decisions are made in that last 15‑minute pre‑submission meeting.

The students who still come out ahead understand two things:

- They spread their bets: not all their work is tied to one overpopulated project.

- They tactically choose projects where they’re the only learner or only writer.

If you attach yourself to a project that already has a fellow, a senior resident, and another student, you should assume first‑author is gone unless someone spells out otherwise.

The students who consistently win first‑author do something slightly ruthless but very smart early on:

They ask, “Is there a project where there isn’t already a fellow or resident leading the writing?” and they gravitate toward those.

What You Should Start Doing Differently Tomorrow

You do not need to be at Harvard. You do not need a 520 MCAT. I’ve watched community‑college‑to‑state‑med‑school students out‑publish Ivy premeds because they understood the game earlier.

If you want to change your trajectory starting now, here’s how to think like an insider.

1. Choose One Mentor Who Actually Finishes Papers

Look at PubMed, not websites. Find someone at your institution who:

- Has published at least 3–4 papers in the last 12–18 months

- Includes students or residents as first or second authors

- Works in a field you can tolerate, even if it is not your dream specialty

Then commit to being “their person” for at least one full project from idea to publication. One clean, fully executed paper teaches you more and signals more than five abandoned half‑projects.

2. Attach Yourself to the Manuscript Stage

The next time you’re offered a project, respond like this:

- “I’d be happy to help with data collection, but I’m especially interested in taking the lead on drafting the manuscript if that’s available. Could we discuss what that would look like and what level of contribution you’d want from me?”

That one sentence tells the PI you’re thinking like a closer, not just a helper.

Once you’re in, start outlining early—even while data is being gathered.

3. Make Yourself the Person Who Never Lets the Ball Drop

Faculty remember two types of students with painful clarity:

- The one who ghosted right when the paper needed to be written

- The one who somehow kept things moving despite rotations, exams, and chaos

You want to be the second category.

That does not mean sacrificing your sanity. It does mean:

- Being realistic about how many projects you can actually carry to completion

- Saying “no” to extra side tasks if they’ll jeopardize the main manuscript

- Keeping communication alive: “I have my surgery exam next week; I can work on this again after date X, is that OK?”

Those students get more offers, more trust, and when a juicy first‑author opportunity appears last‑minute, they’re the first names faculty think of.

FAQs

1. I’m a premed with no research experience. Is it already too late for a first‑author paper?

No. But you need to be strategic. As a premed, your leverage is time, not skill. Approach one productive mentor, be honest that you’re new, and offer to take full responsibility for a clearly defined, finishable project (often a retrospective chart review or systematic review). If you’re persistent over 12–18 months, a first‑author paper before med school is absolutely possible at many institutions, especially in community or VA‑based departments that have tons of data and not enough hands.

2. My current mentor is well‑known but nothing is moving. Should I switch?

If you’ve been on a project for 6–9 months with no clear timeline for a manuscript draft, you need a direct conversation first: “I’d really like to see at least one project through to publication for my applications. Is there a smaller or more defined project we could target for that?” If the answer is vague or you get brushed off, keep the relationship polite but quietly seek a second mentor known for actually getting papers out. Loyalty to a famous but non‑productive mentor will not impress residency programs if your CV is thin.

3. How many first‑author papers do I actually need for competitive specialties?

From what program directors actually say in selection meetings: having 1–2 solid first‑author original research papers in a relevant field already puts you ahead of many applicants, especially if the work looks genuinely student‑driven. For ultra‑competitive fields (derm, ortho, plastics, ENT), applicants are showing up with multiple first‑authors, but often from a dedicated research year. The key is not chasing a magic number. It’s having at least one or two projects where you can clearly articulate your intellectual contribution.

4. What if a PI promised first‑author but then gives it to someone else?

This happens more than people admit. Your leverage is in documentation and professionalism, not confrontation. If you have emails clearly outlining your expected role, you can request a meeting and say: “My understanding from our earlier discussions was that I’d be first author if I carried the manuscript through. Can you help me understand what changed?” Sometimes there are legitimate reasons (another person did unexpected heavy lifting); sometimes it’s politics. How you handle this moment will follow you. Stay calm, protect relationships, and then re‑evaluate whether this is a mentor you keep working with.

5. I’ve been stuck on “data collection” for months. How do I pivot to writing?

You do not need anyone’s permission to start drafting sections that do not require final numbers. Write the introduction with background and rationale. Skeleton out the methods based on the protocol you’re following. Draft a template for tables and figures. Then email your PI: “I’ve started drafting the intro and methods so that once data collection wraps up, we can move quickly. Would you be willing to review a draft in the next few weeks?” This shifts you from anonymous data grunt to visible manuscript owner—exactly where first‑authors are born.

If you remember nothing else, remember this:

First‑author papers don’t go to the “smartest” or the “most passionate.” They go to the students who (1) pick finishable projects, (2) attach themselves to the manuscript phase, and (3) refuse to let a paper die between data collection and publication.

Learn those rules early, and you stop watching other people’s names rise to the top line.

Yours starts showing up there instead.