You’re in a windowless research office at 7:45 pm.

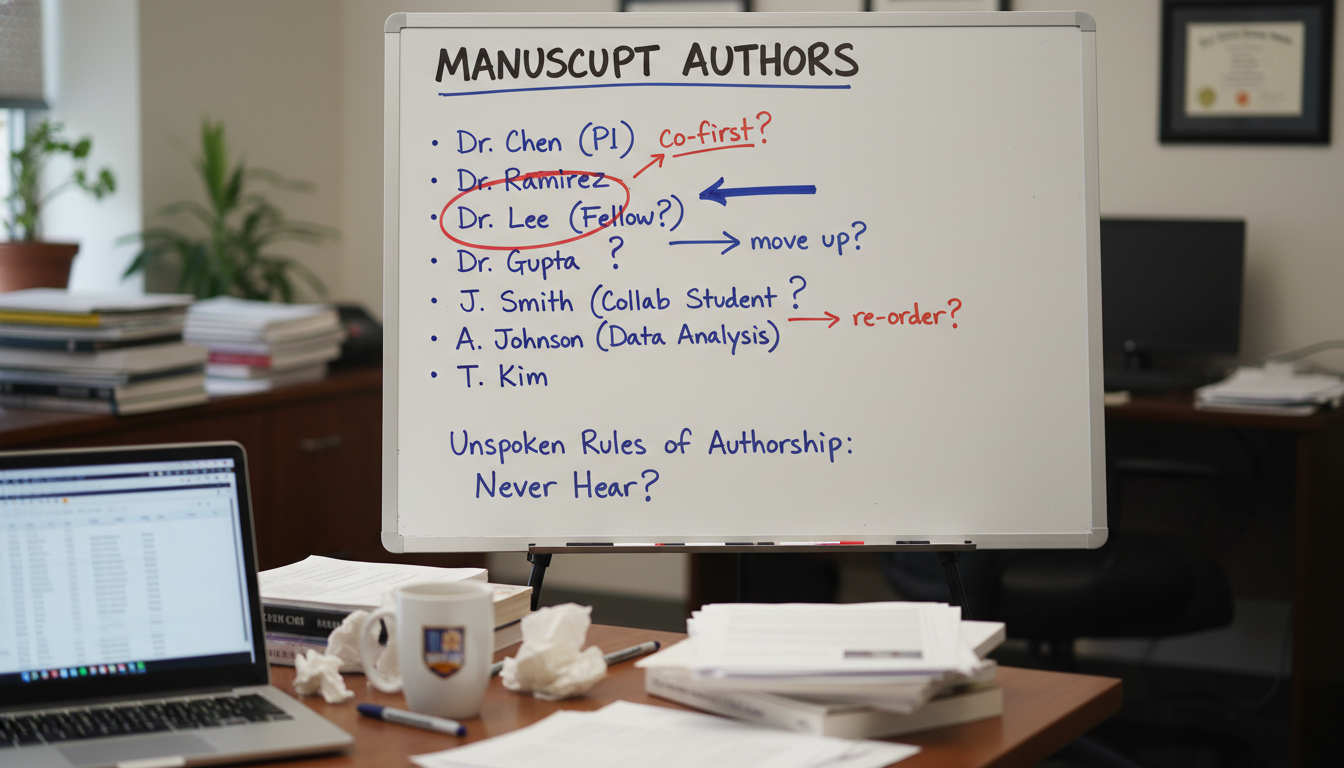

Your PI is scrolling through the manuscript on the big monitor. You finally hit the author list. There it is: your name… fourth. You were in the lab all summer, designed half the methods section, collected most of the data. The second author is a resident you saw twice, both times on Zoom. Third author is the PI’s “collaborator’s student” you have literally never met.

Your mentor pauses for half a second and says, “I’ll finalize the author order later, but this is roughly what I’m thinking.” Then moves on to references.

You nod, say nothing, and feel that mix of confusion, anger, and fear that every ambitious med student or premed experiences at some point:

(See also: What Admissions Committees Think When They See ‘No Research’ for more details.)

Is this just how it is? Did I get screwed? Do I fight this? Do I stay quiet so I don’t burn a bridge?

Welcome to the real game: authorship.

Medical students are told “Do research, get published, it helps your residency application.” What almost nobody explains are the unwritten rules that determine which line on PubMed you get, and how program directors actually read those lines.

Let me walk you through what really happens on the other side of that closed office door.

How Program Directors Actually Read Your PubMed List

Before we get into the politics, you need to understand why author order matters so much.

When program directors open ERAS (or review a premed application packet for competitive MD-PhD or research-heavy MD programs), they do not see “number of publications” and then clap for anyone with a big count. They scan for patterns.

Here’s what they’re actually thinking:

- “Do you have any first-author work?”

- “Are these real papers or 12 co-authorships buried in the middle?”

- “Do your authorship positions progress over time?”

- “Do the projects align with your claimed interests in your personal statement?”

A budding physician-scientist with two solid first-author clinical papers in a relevant field looks far stronger than someone with eight 12th-author case reports spread across random specialties.

No one tells you this explicitly as a student. But I’ve heard this in faculty meetings:

- “This applicant has 9 publications, but they’re all middle author on big consortium studies. Good, but not evidence they can drive a project.”

- “Here’s one with only 3 papers, but two are first author in pulmonary critical care. And the letters mention they wrote the IRB and ran the analysis. That’s impressive.”

So when you’re thinking about authorship, you must think in terms of trajectory and signal, not raw counts. You’re building a story: “I can identify a question, push a project forward, and see it to publication.”

Authorship order is the shorthand for that story.

The Real Hierarchy of Authorship (Not the Version on the Department Website)

Departments love to post neat, sanitized authorship guidelines: “First author did the most work, last author is senior, others contributed meaningfully.”

Reality is messier.

Here’s the rough, unspoken hierarchy in most biomedical research:

- First author – The driver. The person who did most of the hands-on work and a lot of the writing. For med students and premeds, first-author is gold.

- Co–first author – Sometimes legit, sometimes a political compromise. Program directors look at the order in the list, not the footnote. First-listed co–first usually gets more subconscious credit.

- Second author – Often “second-in-command.” If you’re second on a serious project with a strong letter backing your role, that still carries weight, especially early in your training.

- Middle author (3rd–second-to-last) – Variable. Could be anything from critical collaborator to “helped for a week one summer.” Faculty know this. They assume minimal involvement unless a letter says otherwise.

- Penultimate author – In some fields, the main collaborator lab’s PI. In others, just a senior person. For a student, this slot is rare and usually not where you want to be.

- Last author – Senior investigator or lab head. For a student or resident, last author is a separate kind of signal: “I led and supervised this project.” That’s extremely impressive once you’re further along. As a premed/med student, you won’t see much of this early on.

Now the part nobody writes down:

A lot of author order decisions are not about total work done. They’re about power, politics, and future favors.

Examples that happen all the time:

- A department chair tells your PI, “Can you put my fellow high on the paper?” Your PI wants to keep the chair happy. You slide down a spot.

- The “collaborator’s student” who joined late gets middle author ahead of you because there’s a long-standing relationship between labs.

- The resident who “started the project” three years ago but then disappeared gets second author, because they’re about to apply for fellowship and the PI “doesn’t want to screw them.”

None of that appears in the official guidelines. All of it influences your name order.

How Authorship Order Actually Gets Decided Behind Closed Doors

You picture some objective voting system. That isn’t how it works.

Here’s a more accurate description of the process in many labs, especially high-output clinical research shops:

1. The “Default List” Is Written Without You in the Room

The PI, maybe a senior fellow or resident, sits down and throws names into a Word doc:

- Student who wrote IRB, did data collection, made figures – “Okay, probably first.”

- Fellow who helped with early design – “Second?”

- Collaborator’s student who provided one dataset – “Let’s stick them third.”

- Statistician – “Middle somewhere.”

- PI and co-PI – Last two slots.

You see it only once it’s essentially “decided.” That’s why the first conversation about authorship should never be at the submission phase. If you wait that long, you’re negotiating from a position of weakness.

2. “Contribution” Gets Filtered Through Memory and Politics

Your PI is not keeping a detailed time log of who did what. They’re going off:

- Who emails them the most

- Who’s visible in meetings

- Who they promised what, months ago

- Which relationships they’re trying to protect

If you quietly did 100 hours of data collection but never said a word, and the fellow loudly presented slides a few times, the fellow’s contribution may feel larger in the PI’s mind.

This is one of the harsh truths: how your contribution is perceived often matters more than the raw hours you put in.

3. Late Favors and “Can We Add So-and-So?”

A common pattern:

- Manuscript is nearly done

- Another faculty member gave you some key stats help or access to patients

- PI says, “We should add them and maybe their student”

They almost never get first or last. So guess what moves? The middle.

Often your name shifts one or two spots down to make room. Nobody tells you explicitly. You see it in the “final draft.”

4. The PI Balances Guilt and Utility

Some PIs do genuinely try to be fair. They’ll sit there thinking:

- “The student did a lot. They should be first.”

- “But my fellow needs a strong second-author for fellowship.”

- “The chair’s mentee has to appear somewhere high.”

So they compromise. You keep first. Someone else gets a higher middle spot than they arguably deserve. Or, worst case, your first slides to second in order to “help” a more senior trainee.

You will never hear: “I moved you down for political reasons.” You’ll hear vague things like “overall contribution,” “project leadership,” or “continuity.”

If you’re not prepared, you just swallow it.

The Conversations You Should Be Having Early (But No One Tells You To)

Most students never talk about authorship until the writing phase. That’s too late.

The faculty who keep their students happy do one simple thing: they set expectations within the first 2–4 weeks of the project.

Here’s what that actually sounds like when it goes well:

You: “Dr. Smith, I’m really excited about this chart review on post-op complications. Could we briefly clarify expectations? If I handle the IRB, most of the data collection, and the first draft of the manuscript, would that typically be enough to be considered for first authorship in your group?”

A good mentor responds with something concrete:

- “Yes, in my lab, that level of work is usually first-author.”

- Or, “Probably co–first with the resident who developed the protocol.”

- Or, “For this one, the fellow will likely be first, but you’d be second or third if you do what you just described.”

Now you have a rough framework. It’s not a contract, but it’s a reference point. Later, if author order doesn’t match, you can calmly say:

“You mentioned at the beginning that if I did X, Y, Z I’d likely be first or co–first. I believe I completed those. Can we revisit the authorship order?”

That’s a very different conversation from a last-minute emotional outburst.

Premeds and early med students avoid these talks because they feel “pushy.” What you do not see is that the residents and fellows behind you are having these conversations. Quietly. Clearly. And they’re getting the better slots.

You do not have to be aggressive. You do have to be explicit.

The Quiet Power Moves That Protect Your Authorship

Here’s what the savvy students do—usually because an older resident clued them in late at night on call.

1. Document Your Contribution As You Go

Not a manifesto. Just simple, factual records:

- Dates you worked on the IRB or protocol

- How many charts you abstracted

- Which figures or tables you built

- Sections of the manuscript you drafted or revised

Every few weeks, send brief, neutral updates to your mentor:

“Quick update: I’ve completed data collection on 120/200 patients and drafted the Methods section. Next, I’ll start the Results tables unless you’d like me to focus elsewhere.”

This does three things:

- Keeps you visible

- Creates a written trail showing you as the driver

- Makes it much harder for anyone to minimize your role later

When authorship questions come up, your mentor can look back and think, “Right, this student has been pushing this the whole time.”

2. Make Yourself the Project’s Center of Gravity

You want to be the person who:

- Schedules the Zoom meetings

- Circulates agendas

- Sends out action-item summaries

- Reminds people of deadlines

When you’re the organizational hub, you’re seen as central. That bleeds into authorship decisions.

I’ve sat in rooms where PIs said, “Let’s keep them first. They’ve been holding this together.”

3. Ask Directly When Projects Drift

Sometimes your role shrinks mid-project because the design changes or someone else swoops in. You need to notice and react.

You: “Dr. Lee, I’ve noticed that since we added the new imaging cohort, the radiology fellow has taken a larger role, which makes sense. Could we touch base on what authorship position I should realistically expect now, and what I can do to maintain a strong role?”

You’re showing awareness, not entitlement. You’re also forcing clarity rather than silently sliding down the list.

4. Know When to Walk Away (Strategically)

There are mentors and labs with reputations. You’ll hear it in whispered hallways:

- “Great at getting papers out, but students never get first author.”

- “Will promise you a lot, but when submission time comes, you’re suddenly 6th.”

If you spot those patterns early, do not chain yourself to that lab for all of med school. Take the middle-author win if it’s almost done, then quietly invest your main energy with someone else, ideally in a group with a track record of giving students meaningful authorship.

Program directors can tell when a student has one “token” middle-author paper from a powerhouse lab plus one or two first-authors from a smaller, student-friendly shop. They don’t penalize you for that. They respect the first-authors.

When You Realize You’ve Been Unfairly Downgraded

This is the nightmare scenario: you did the work, you were informally promised a top position, and then the draft comes back and you’re buried.

You have three options. Most students only see one.

Option 1: Say Nothing and Swallow It

That’s what the majority do. They’re terrified of confrontation, bad letters, or being blacklisted. Sometimes this is the least-bad choice—if the project is minor, the mentor has a lot of power, and you’re months from ERAS or med school applications.

But if this becomes your default, you’ll repeatedly lose ground you earned.

Option 2: Emotional Confrontation (Don’t)

You corner your PI in the hallway and say, “I don’t understand why I’m fourth author. I did all the work. This isn’t fair.”

They feel attacked; you look unprofessional. There’s no record. They may grudgingly bump you up one slot, but you’ve likely burned trust.

Faculty talk. You do not want to be known as “the student who blew up about authorship.”

Option 3: Calm, Written, Specific Pushback (The Grown-Up Move)

You send a short, composed email or request a brief meeting:

“Dr. Patel, I wanted to thank you for including me on the manuscript draft. I did have a question about the authorship order. At the beginning of the project, we discussed that if I completed the IRB, full data collection, and initial manuscript draft, I’d likely be considered for first- or second-author. I believe I’ve completed those tasks. Could you help me understand the decision for the current author order, and whether there’s room to revisit it?”

Key elements:

- You reference the earlier expectations (if they exist)

- You list specific contributions, not “I worked really hard”

- You ask to “understand,” not demand change

- You leave the door open to revision

Responsible mentors will at least give you an explanation. Many will adjust the order if they realize they stretched fairness too far. The less responsible ones will gaslight or stonewall you. With those, you file that information away and never depend on them again.

Will this always fix it? No. But I’ve seen many students rescued from unfair middle authorship because they pushed—once, professionally, on the record.

How to Talk Authorship as a Premed vs. as a Med Student

Premeds and med students do not have the same leverage, and faculty subconsciously know this.

As a premed:

- You’re often joining projects already in motion

- You’re seen as more transient and less experienced

- PIs may assume you “won’t notice” the nuances of author order

So your moves are:

- Clarify from day one what level of work typically leads to authorship at all

- Aim for any authorship on early projects, but be direct if you’re doing first-author-level work

- Use smaller, well-defined projects (case reports, short chart reviews) with clear author expectations to get your first line or two

As a med student:

- You can credibly say, “These publications will heavily impact my residency application”

- You often stay longer in a lab or with a mentor

- You may have older students/residents who can vouch for your work style

So your moves get bolder:

- You should explicitly ask, “Is this structured as a potential first-author project for me?” when you take on something big

- You can prioritize projects and mentors with proven student first-authors

- You can leverage your track record (“On my last project with Dr. X, I successfully led a manuscript to publication as first author”) to negotiate role on new projects

In both cases, you never threaten, you never beg. You ask clear questions, you document your work, and you choose your mentors strategically.

When Being Middle Author Is Actually Fine

None of this means middle authorship is useless. That’s another myth.

For premeds and early med students, middle-author roles can be:

- A way to get your foot in the door with a busy lab

- A low-risk method to learn how papers are assembled

- A quick bump in your “peer-reviewed publication” count

The trick is timing and proportion.

If your entire output after three years is six middle-author lines with no clear story, that’s weak. If you have one or two first-author or second-author manuscripts plus some middle-author work, that’s a solid portfolio.

I’ve heard PDs say with a shrug, “They clearly worked with a productive group and contributed across projects. The first-author paper in cardiology is what convinces me they can really lead something.”

Treat middle-author work as seasoning, not the main dish.

The One Thing You Must Remember

Nobody is going to care about your authorship more than you do.

PIs are juggling grant deadlines, promotions, politics, their own kids, and twenty other manuscripts. They’re not sitting at night thinking, “Was I perfectly fair to that one med student on that one paper six months ago?”

They’re thinking, “I need this submitted this week before the grant goes in.”

Your job is not to fight every small slight. Your job is to:

- Choose your mentors and labs with more care than most students do

- Have explicit authorship conversations earlier than feels comfortable

- Make your contributions so visible and well-documented that it’s easier to be fair to you than to sideline you

You will not win every battle. Even seasoned faculty get burned on authorship. But over four years of med school (and even in your premed years), following these unspoken rules shifts your trajectory.

You move from the student who’s “grateful just to be on the paper” to the one whose CV actually tells a story of leadership, ownership, and follow-through.

That’s the story program directors recognize instantly—because they’ve lived the other side of it for years.

Key points to walk away with:

- Program directors and selection committees care far more about authorship position and trajectory than raw publication count.

- Authorship order is shaped by perception, politics, and early expectation-setting—so you must talk about it explicitly and document your role as you go.

- Your leverage comes from choosing mentors wisely, making yourself the project’s center of gravity, and pushing back once—calmly, specifically—when reality drifts too far from what you were promised.