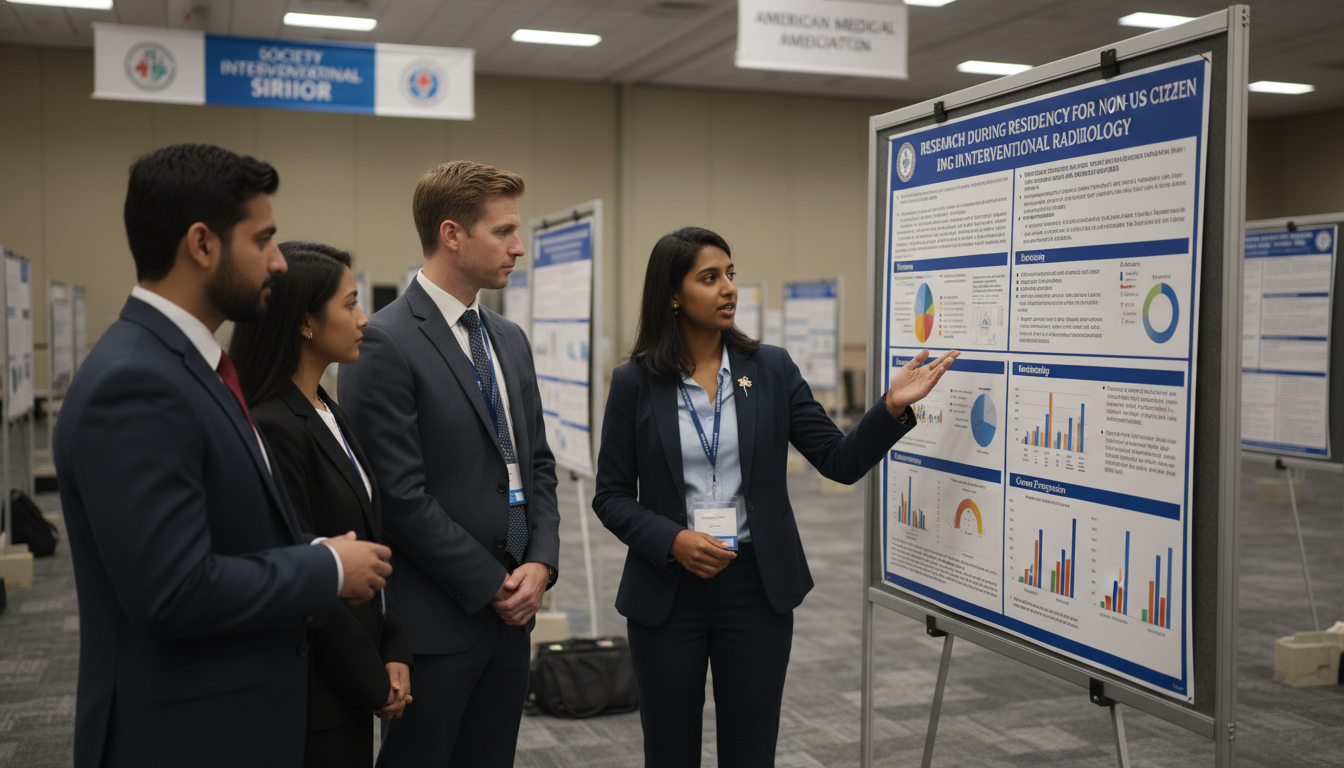

Understanding the Value of Research During an IR Residency as a Non‑US Citizen IMG

For a non-US citizen IMG (international medical graduate), research during residency is more than a “nice-to-have.” In interventional radiology (IR), it can be a powerful tool that:

- Differentiates you in competitive environments

- Strengthens your case for visas and future academic positions

- Builds networks that support fellowships and jobs

- Provides a pathway into an academic residency track or junior faculty roles

As a foreign national medical graduate, you may arrive at residency with fewer US contacts, less familiarity with local research systems, and additional visa pressures. This does not mean you are at a disadvantage; it means you must be more strategic and intentional.

This article breaks down how to think about research during residency, how to get started early, how to balance clinical and academic responsibilities, and how to convert resident research projects into tangible career advancement—specifically for interventional radiology and the IR match pipeline.

Why Research Matters So Much in Interventional Radiology

Interventional radiology is uniquely positioned at the intersection of imaging, procedures, and innovation. New devices, techniques, and image-guided therapies are continuously emerging. Programs expect IR residents—especially those with academic ambitions—to be comfortable with:

- Critical appraisal of the literature

- Designing and executing clinical or translational studies

- Presenting at national and international meetings

- Contributing to the evidence base for IR procedures

How Research Supports Your Long-Term Career as an IMG

For a non-US citizen IMG, research during residency is often directly tied to long-term goals:

Competitiveness for Fellowships and Jobs

- Many top fellowships and academic IR positions favor candidates with publications, abstracts, or significant resident research projects.

- Programs know that a strong research record predicts productivity, curiosity, and leadership.

Visa-Related Advantages

- For those eventually considering an O‑1 (extraordinary ability) visa or EB‑1/NIW permanent residency pathways, a robust publication and citation record can be critical.

- Letters from research mentors and evidence of national-level presentations strengthen these applications.

Building Professional Identity in the US System

- As a foreign national medical graduate, you may lack a built-in network. Research supervisors, co-authors, and collaborators become your US-based advocates for the IR match, fellowships, and jobs.

- You gain familiarity with US research ethics, IRB processes, and publication standards.

Positioning for an Academic Residency Track or Faculty Role

- Many institutions have an academic residency track or “resident scholar” pathway. Sustained research productivity during residency is often the main selection criterion.

- Early research can evolve into career-defining niches (e.g., interventional oncology, peripheral arterial disease, venous interventions, women’s IR).

Getting Started: Laying the Groundwork in Early Residency

Clarify Your Goals in PGY‑1/PGY‑2

Before you commit to big projects, answer these questions:

- Do you see yourself in academic IR or primarily clinical/private practice?

- Are you interested in clinical research, quality improvement (QI), education research, or translational/bench research?

- How will research help your next step: IR match (if in ESIR/DR), fellowship, or early career?

Even if you are unsure, assume you might want academic options later; it is much easier to build a research record now than to start from zero as a fellow.

Map the Research Ecosystem at Your Institution

As soon as possible in residency:

Identify IR Faculty with Research Roles

- Look for IR attendings with titles like “Director of Research,” “Section Chief,” or “Associate Professor.” Check their departmental web pages and PubMed.

- Note their interests: e.g., interventional oncology, vascular interventions, trauma IR, neurointervention, IR in pediatrics.

Find Active Projects That Need Help

- Ask senior residents/fellows which attendings are “resident-friendly” mentors.

- Join existing projects first; starting with something midstream is often faster than inventing your own project from scratch.

Learn the Administrative Pathways

- Who manages the IRB (Institutional Review Board) office?

- Is there a research coordinator for IR or radiology?

- Are there departmental templates for retrospective chart reviews, data use agreements, or REDCap databases?

Key First Steps for a Non-US Citizen IMG

Clarify visa-related work restrictions early.

- J‑1 and H‑1B visas usually allow research within your training institution, but external paid consulting may be restricted.

- Ask your GME office if there are any limitations related to off-site projects or moonlighting.

Understand your time budget.

- In IR/DR pathways, schedule intensity varies. Identify lighter rotations where you can schedule research blocks or writing time.

- Block out 1–2 protected hours per week for research as a minimum baseline, even during busy months.

Choosing the Right Types of Resident Research Projects

The best resident research projects are those that are:

- Feasible within your time and resource constraints

- Likely to produce something presentable or publishable

- Aligned with your long-term interests and potential academic niche

Below are common options, with pros and cons tailored to non-US citizen IMGs in interventional radiology.

1. Retrospective Clinical Studies

Example: Outcomes of TACE vs. Y‑90 in hepatocellular carcinoma at your institution; complication rates of tunneled catheter placements; re-intervention rates after iliac vein stenting.

Pros:

- Typically faster to start (no prospective recruitment).

- Often suitable for residents with limited time.

- Directly relevant to clinical IR practice and valued by IR programs.

Cons:

- Requires access to clean data and support for data extraction.

- May face IRB hurdles if data de-identification and HIPAA concerns are not handled carefully.

Actionable tip: Ask if your department already has a prospectively maintained IR database. If yes, propose a subproject examining a specific procedure or outcome.

2. Case Series and Case Reports

Example: Rare complications of endovascular procedures; innovative use of existing devices; first successful use of a new embolic agent in a special population.

Pros:

- Excellent entry point especially early in residency.

- Fast turnaround, often with friendly IR journals open to submissions.

- You learn the full cycle of research: literature review, drafting, submission, revisions.

Cons:

- Lower impact than large original research studies.

- Hard to build an entire academic residency track profile on case reports alone.

Actionable tip: During IR rotations, maintain a personal “interesting case log.” Discuss potential publishable cases with attendings as they occur, not months later.

3. Quality Improvement (QI) and Workflow Projects

Example: Reducing door-to-groin-puncture time in stroke thrombectomy; optimizing radiation dose in CT-guided biopsies; improving documentation of sedation time.

Pros:

- Often easier IRB pathway (sometimes QI is exempt).

- Highly valued by program directors and hospital leadership.

- Presents well at institutional and regional meetings.

Cons:

- May be overlooked by national IR journals unless rigorously carried out.

- Requires buy-in from multiple stakeholders (techs, nursing, schedulers).

Actionable tip: Tie your QI project to hospital metrics or national benchmarks (e.g., stroke guidelines). This increases institutional support and makes the work more impactful.

4. Educational Research

Example: Novel simulation curriculum for central line placement; flipped classroom model for IR teaching; evaluating residents’ procedural competency over time.

Pros:

- Good option if you enjoy teaching and are considering an academic residency track.

- Often publishable in radiology education or medical education journals.

- May require fewer patients and more surveys, OSCE scores, or curriculum outcomes.

Cons:

- Requires some familiarity with survey design and educational frameworks.

- Educational journals may not carry the same weight as high-impact clinical journals, though they are still highly valuable.

5. Translational/Bench Research

Example: Device development, new embolic materials, imaging biomarkers in oncology.

Pros:

- Highly valued for academic IR careers at major research centers.

- Potential for patents, collaborations with engineering or industry.

Cons:

- Time-intensive; sometimes unrealistic within standard residency schedules.

- Requires lab access, grants, and sustained mentorship—more challenging for a non-US citizen IMG without prior US-based lab connections.

Actionable tip: If you already have substantial basic science experience from abroad, leverage it to join an existing IR-related lab; otherwise, focus first on clinical/QI projects that are more feasible during residency.

Making Research Work Within a Busy IR Residency Schedule

Interventional radiology training is demanding: long procedural days, call, and shared DR responsibilities. For research during residency to succeed, you must be methodical.

1. Plan Long-Term, Act Short-Term

Create a 12–24 month research roadmap.

- Aim for a mix: one or two major retrospective/QI projects + several shorter items (case reports, letters, abstracts).

- Set milestones: IRB approval, data collection complete, first draft, submission, revision.

Break goals into weekly tasks.

- Example: “This week: complete 20 chart reviews, draft methods section, update mentor.”

2. Use Light Rotations Strategically

- Identify rotations with lower call or procedural volume (e.g., certain DR rotations, elective blocks, night float downtime) and schedule research pushes there.

- Request an “academic half-day” if your program allows it, clearly explaining your research objectives and progress.

3. Build Efficient Habits

- Learn basic data tools early: REDCap, Excel, R or Python basics, or at least SPSS.

- Use a reference manager (Zotero, Mendeley, EndNote) from day one.

- Maintain a “research log” documenting:

- Project name and aim

- IRB status

- Data source and variables collected

- Your specific responsibilities and deadlines

4. Protect Time from Erosion

- Put research blocks on your calendar as if they were clinical appointments.

- Treat writing sessions (even 30 minutes) as non-negotiable.

- Politely set expectations with co-residents: “I’m working on a manuscript tonight, can I switch cross-coverage days with you?”

5. Communicate Proactively With Mentors

- Agree on preferred communication style (email, scheduled Zooms, in-person).

- Send brief progress updates every 2–4 weeks, even if small: “Collected 40/120 patients, preliminary complication rate seems to be X%.”

- Before meetings, prepare a simple agenda and specific questions—this increases mentor engagement and confidence in you.

Turning Resident Research into Publications, Presentations, and Future Opportunities

Simply “doing research” is not enough; you must convert your work into visible, citable outputs that will strengthen your academic portfolio and career trajectory.

From Project to Abstract to Manuscript

Aim for Presentations First

- Submit abstracts to:

- SIR (Society of Interventional Radiology)

- RSNA (Radiological Society of North America)

- Regional societies (e.g., local radiological societies, state IR meetings)

- Presenting a poster or talk gives early feedback and is a strong line on your CV.

- Submit abstracts to:

Then Focus on Manuscripts

- After a successful abstract, convert the work into a full paper.

- Target journals:

- IR-focused: Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology (JVIR), CVIR, CVIR Endovascular

- Radiology/general: Radiology, AJR, European Radiology

- Specialty: vascular, oncology, hepatology journals, depending on topic

Use Templates and Models

- Read 2–3 similar IR papers and mirror their structure (Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion).

- Maintain a standard checklist: STROBE for observational studies, CONSORT for randomized trials, etc.

Authorship and Credit: Protecting Your Contributions as an IMG

As a non-US citizen IMG, you may feel hesitant to negotiate authorship. However, it is important to:

Clarify roles upfront:

- Who is first author, second author, senior author?

- Who will write which sections? Who handles submission and revisions?

Ask directly but respectfully:

- “If I am responsible for data collection and drafting the manuscript, would first authorship be appropriate?”

- “How do you usually decide author order for resident research projects?”

Keep documentation via email summarizing agreed roles. This also helps if faculty or residents graduate or leave.

Connecting Research to the IR Match and Beyond

For those in a DR-to-IR pathway (or ESIR), your research experience directly influences your IR match prospects:

During IR interviews, be prepared to:

- Summarize each project in 2–3 clear sentences.

- Explain your role (data collection, analysis, writing, project design).

- Discuss what you learned and how it shaped your interest in specific IR subspecialties.

For an academic residency track or future academic role, highlight:

- Consistent output (e.g., a poster every year plus one or more publications).

- Evidence of leadership (you initiated or led a multi-resident project).

- Any grants or small institutional awards you received.

Building a Recognizable Niche

IR is broad. To stand out:

- Look for recurring themes in your projects: e.g., interventional oncology, venous disease, women’s IR, pediatric IR, stroke.

- Over time, try to cluster research around one or two areas, so you can be seen as “the resident with a developing expertise in X.”

Navigating Common Challenges for Non-US Citizen IMGs

1. Adapting to US Research Culture and Expectations

Documentation and compliance are taken very seriously. Get comfortable with:

- IRB training modules (e.g., CITI Program).

- Data privacy rules (HIPAA).

- Conflict-of-interest disclosures.

Ask questions early: If you are unsure about whether something needs IRB approval, ask your mentor or the IRB office. Never assume.

2. Overcoming Limited Prior Research Experience

Many foreign national medical graduates did not have robust research infrastructure in their home countries. To catch up quickly:

Take advantage of free or institutional resources:

- Online courses in biostatistics, epidemiology, and scientific writing (Coursera, edX, institution’s CME).

- Library consultations—most academic hospitals have librarians who help with literature searches and reference management.

Start with small, winnable projects:

- Single case report

- Small retrospective series

- Co-authoring introductions or discussion sections for larger projects

3. Dealing With Time Pressure and Burnout

Balancing call, procedures, and research can be exhausting.

Prioritize quality over quantity: A few robust projects with publications are more valuable than 10 unfinished ideas.

Learn to say no diplomatically:

- “Thank you for thinking of me; my current projects and clinical duties are at capacity. I wouldn’t be able to give this project the attention it deserves.”

Protect your physical and mental health; no research achievement is worth severe burnout.

4. Considering Long-Term Visa and Career Strategy

If you aim for long-term practice in the US:

Keep an organized portfolio of:

- Publications (accepted and in-progress)

- Conference presentations and invited talks

- Awards and recognitions

For potential O‑1 or EB‑1 in the future, evidence of being “internationally recognized” for your work includes:

- First-author publications in recognized journals

- Presentations at major IR or radiology conferences

- Peer-reviewing for journals (once you gain experience)

- Letters from well-known IR researchers outside your institution

Working with an experienced immigration attorney later in your training can help you leverage your research achievements effectively.

Practical Example: A 3-Year Research Plan for an IR-Bound non-US Citizen IMG

PGY‑1/PGY‑2 (Early DR years)

- Join one retrospective IR outcomes project as a co-investigator.

- Write at least one case report based on an interesting IR case.

- Present a poster at a regional or national radiology meeting.

PGY‑3/PGY‑4

- Lead your own QI project (e.g., stroke workflow optimization).

- Become first author on one full-length original IR paper.

- Present at SIR or RSNA; network with academic IR faculty.

- Consider applying for an academic residency track, if available.

PGY‑5/PGY‑6 (ESIR/Independent IR years)

- Develop a small “niche” (e.g., interventional oncology or venous interventions).

- Complete an additional study in that niche and target a respected IR journal.

- Serve as mentor or collaborator for junior residents on new projects.

- Use your cumulative research profile to strengthen fellowship/job and, if relevant, visa applications.

FAQs: Research During Residency for non-US Citizen IMGs in Interventional Radiology

1. Do I need prior research experience before residency to be successful in IR research?

No. Many non-US citizen IMGs start residency with little formal research training. What matters is your willingness to learn quickly, your reliability, and your ability to complete projects. Starting with smaller, mentored projects and building stepwise experience can lead to a strong research record by the end of residency.

2. How much research output is “enough” for an academic IR career?

There is no strict number, but by the end of residency (and IR training), a competitive academic candidate might have:

- Several poster or oral presentations at national meetings (SIR, RSNA, etc.)

- Multiple peer-reviewed publications (ideally with at least one first-author paper)

- Evidence of leading or co-leading significant resident research projects

Quality, relevance to IR, and consistent productivity matter more than pure quantity.

3. Can research during residency help if I plan to work in private practice IR?

Yes. Even if you plan on a predominantly clinical career, research experience helps you:

- Read and apply literature more critically

- Improve quality and safety in your own practice

- Stand out in the IR match and fellowship selection

- Keep the option open for future academic or hybrid roles

Private practices also value physicians who can lead QI projects and contribute to practice optimization.

4. Are there special considerations for foreign national medical graduates regarding funding or paid research roles?

As a non-US citizen IMG on J‑1 or H‑1B status, you can usually participate in research at your sponsoring institution without separate authorization. However:

- Paid research roles outside your residency program or institution may conflict with visa rules.

- Before accepting any paid research consulting or off-site work, consult your GME office or an immigration specialist.

If you seek formal research funding (e.g., grants), discuss eligibility criteria with your mentors and institutional grants office early.

Research during residency is one of the most powerful tools you have as a non-US citizen IMG in interventional radiology. With deliberate planning, strong mentorship, and realistic projects, you can transform your years of training into a springboard for a fulfilling, impactful, and secure IR career—whether in academic medicine, a hybrid role, or advanced clinical practice.