It is August 1st. You are a rising sophomore premed, staring at your empty CV and a dozen research flyers on the bulletin board. Some projects want a 6‑week summer commitment. Others hint at “multi‑year longitudinal work” and “potential for publication.” You are not sure what to pick, how many to juggle, or how to avoid getting trapped in a 3‑year project that never yields a paper.

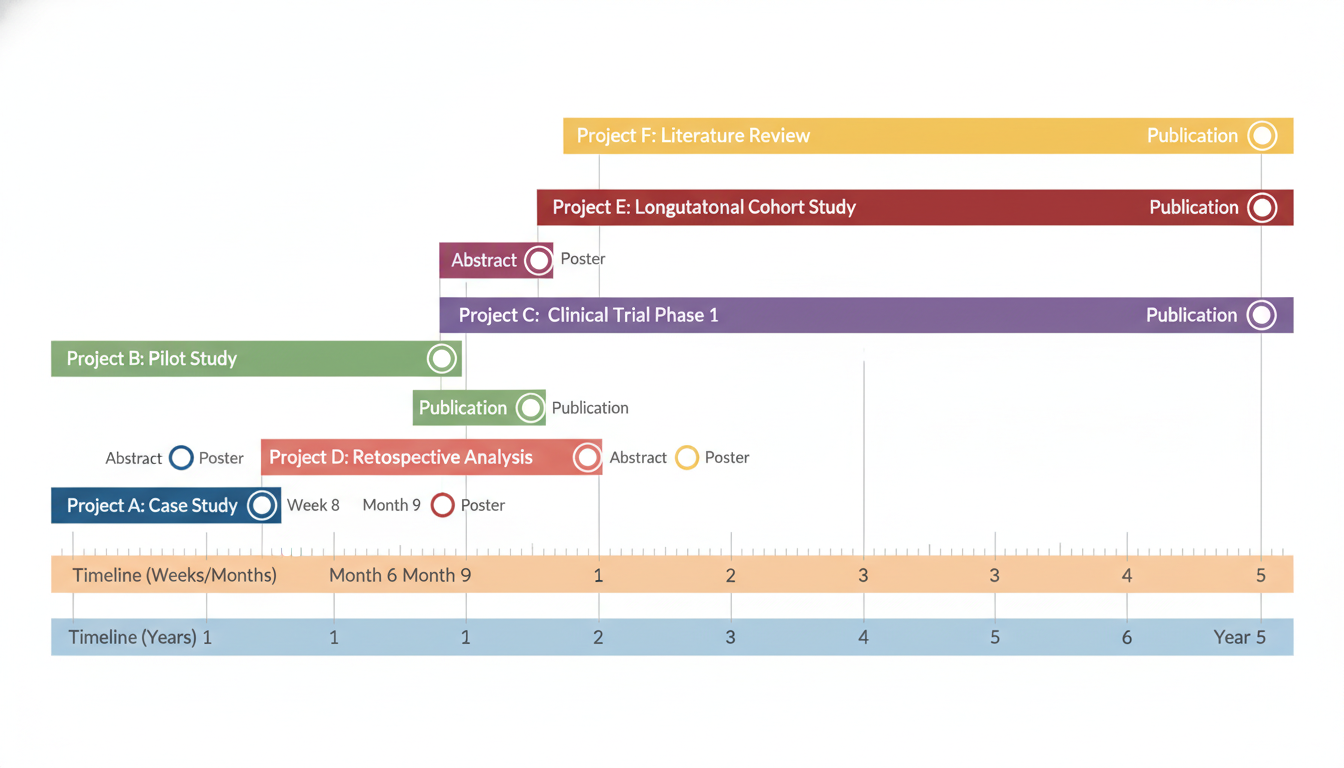

At this point you need more than “do research.” You need a layered timeline: short‑term projects that give you quick skills and products, stacked under long‑term projects that mature slowly but impress admissions committees.

This guide walks you month‑by‑month and year‑by‑year through building that stack from late high school through the first year of medical school.

Year‑by‑Year Overview: How Your Research Layers Should Look

Think of your research life as three overlapping timelines:

- Foundation timeline – learning skills, joining labs, basic tasks

- Short‑term project timeline – 2–12 week sprints with clear endpoints

- Long‑term project timeline – 1–3+ year arcs that aim for presentations, publications, or leadership

At each stage, you should know:

- What to start

- What to sustain

- What to finish

Late High School / Gap Year (T‑4 to T‑3 years before med school)

Goal: Exposure and basic skills, 1–2 simple outputs.

At this point you should:

- Prioritize short‑term research-like experiences:

- Summer research programs for high school students

- Shadowing researchers

- Helping with basic data entry or literature reviews

- Start one possible long‑term relationship:

- A lab at a nearby university you can return to each summer

- A mentor you can continue to email and assist remotely

Your timeline here is light. Focus on learning what research actually looks like and whether you like it.

Premed Year‑by‑Year: Building the Layered Timeline

Freshman Year (T‑3 years before medical school)

You are just arriving on campus. MCAT is distant. Research is optional but valuable.

Fall (September–December)

At this point you should not overcommit. Your research actions are reconnaissance.

Weeks 1–4: Exploration only

- Attend:

- Departmental research fairs

- Premed club research nights

- Seminars where faculty present their work

- Make a list of:

- 5–10 labs whose topics you find genuinely interesting

- 2–3 types of research: bench, clinical, public health, education, qualitative, etc.

Weeks 5–8: Light contact and skill-building

Layer 1: Foundation

- Enroll in:

- A statistics or data science intro course (if available)

- A basic programming course (Python, R) or online equivalent

- Email:

- 3–5 faculty with a concise, tailored message and 1‑page resume

- Emphasize willingness to start with simple tasks and learn skills

You are not chasing a long‑term project yet. You are trying to gain entry.

Weeks 9–14: Join 1 lab at low intensity

Target:

- 3–5 hours/week maximum

- Clear, simple tasks:

- Data cleaning

- Literature searches

- RedCap entry

- Basic wet lab techniques under supervision

Your timeline for this first semester:

- Short‑term goal (by December 15):

- Understand the project’s main question

- Learn the basic workflow

- Build credibility by being reliable

- No pressure for publications yet. Your product is trust.

Spring (January–May)

Now you start stacking.

January: Decide what to keep

At this point you should:

- Keep the lab if:

- You like the environment

- Someone is willing to mentor you

- There are defined projects students work on

- If not, use January to pivot:

- Shadow a different lab

- Attend 1–2 different research group meetings

February–April: Add your first short‑term project

Layer 2: Short‑term, tightly scoped

Examples:

- A literature review that feeds into a larger project

- A small retrospective chart review:

- Defined dataset

- One primary hypothesis

- 2–3 variables

- A quality improvement (QI) project in a clinic:

- Ex: Improving vaccination reminder calls over 8 weeks

Timeline pattern:

- Weeks 1–2: Narrow the question with your mentor

- Weeks 3–6: Do the main work (data pulling, chart review, lit review)

- Weeks 7–10: Create 1 product:

- Poster for a campus research day

- Abstract draft for a regional meeting

- Internal report for the clinic or lab

You now have:

- 1 ongoing lab affiliation (long‑term potential)

- 1 concrete short‑term project that finishes in under a semester

May–August: Test long‑term commitment over the summer

If you can stay near campus:

- Increase to 15–20 hours/week in your lab

- Ask for a summer‑length mini‑project that:

- Starts in May

- Ends with a poster by August

If you must leave campus:

- Request remote tasks:

- Data coding

- Qualitative transcription

- Literature synthesis

At this point you should evaluate:

- Is this a lab you can envision staying in for 2–3 years?

- Is there a multi‑year question you could own a piece of?

You are deciding where your true long‑term project will live.

Sophomore Year (T‑2 years before medical school)

This is the key year for layering short‑term and long‑term research so that they mature in time for applications.

Big Picture for Sophomore Year

By the end of this year, aim to have:

- 1 established long‑term project with:

- Clear role

- Defined endpoint (paper, major presentation, or thesis)

- 1–3 short‑term projects that become:

- Posters

- Abstracts

- Small co‑authorships

Fall (September–December)

September: Lock in the long‑term home

At this point you should:

- Confirm with your primary mentor:

- That you will stay involved through at least junior spring

- That there is a project where your sustained effort makes sense

- Ask directly:

- “What multi‑semester project could I take ownership of a small but meaningful part of?”

Examples of long‑term project types:

- Prospective clinical study recruiting patients over 18–24 months

- Longitudinal educational research following a cohort through a curriculum

- Bench project requiring months of optimization before final experiments

- Large database study with multiple related papers planned

October–November: Define the long‑term project timeline

You want a written outline that looks like this:

- Phase 1 (Now–December): Background, protocol refinement, IRB exposure

- Phase 2 (January–August): Data collection or main experimental phase

- Phase 3 (Next September–March): Data analysis and manuscript / abstract

- Phase 4 (Next April–June): Submission to conference or journal

At this point, that document does not need to be perfect. It just needs to exist.

In parallel, run one short‑term project:

- Example:

- Secondary analysis of already collected data

- Small subset of a larger trial for a local poster

- Timeline:

- 8–10 weeks from start to poster

You are learning to ride two horses: one sprint, one marathon.

Spring (January–May)

January–February: Deep in the long‑term, quick in the short‑term

Long‑term:

- Focus on:

- Recruitment

- Running standardized procedures

- Month‑by‑month metrics (how many patients, how many samples)

Short‑term:

- Launch a mini‑project that can finish by May:

- Methodological poster

- Education pilot study with pre/post surveys in one course

- A case report with a resident (very short timeline but publication‑oriented)

Target structure:

- Long‑term: 5–10 hours/week

- Short‑term: 3–5 hours/week during peak weeks

March–May: Produce visible outputs

By the end of sophomore year, at this point you should have:

- 1 presentation or accepted abstract (campus or regional)

- Clear evidence that your long‑term project is progressing:

- Recruitment numbers

- Partial dataset

- Draft figures or tables

If your long‑term project is stalled with no clear path, this is the last moment to pivot to a different lab and still have a strong story by application time. Have that conversation in April, not October of junior year.

Summer after Sophomore Year (T‑1.5 years before med school)

This is your high‑intensity research window.

You should:

- Push your long‑term project hard:

- Finish data collection or move it 70–90% to completion

- Start preliminary analyses with your mentor

- Run at least one structured short‑term project:

- A discrete sub‑analysis

- A second abstract from a different angle on the same dataset

- A separate collaboration in another lab with a 10‑week deliverable

Concrete goals by August:

- One poster submitted (or presented) related to your long‑term project

- One manuscript outline drafted, even if not ready to submit

- Clear timeline from your mentor:

- “We expect to submit this paper by [Month X of junior year].”

If that sentence cannot be said with a straight face, your timeline for publication may not align with your application cycle. Adjust expectations and emphasize presentations and meaningful role instead.

Junior Year (T‑1 year before medical school, traditional applicants)

Your primary constraint is the AMCAS application opening in late May to early June.

Working backward:

- AMCAS submitted: June after junior year

- Activities section locked: content should be ready by April

- That means your strongest research stories must exist by March, not August.

Fall (September–December)

At this point you should already be:

- Deep in analysis for your long‑term project

- Harvesting outputs from your short‑term projects

September–October: Consolidate, then selectively add

Priorities:

- Finish things:

- Convert posters into abstracts or manuscripts

- Merge small tasks into coherent stories (“Over 2 years I did X, Y, Z within this lab”)

- Avoid new long‑term commitments unless:

- They can produce an abstract or defined product by March

You can still add:

- Micro‑projects that fit 6–8 week windows:

- Case reports

- Short commentaries or letters to the editor

- Very small QI projects with immediate data

Time budget:

- Long‑term project: 5–8 hours/week (heavier during analysis and writing)

- Short‑term projects: 2–4 hours/week, and only when they have clear deadlines

November–December: Lock in what will appear on your application

By December, at this point you should know:

- Your 1–2 “most meaningful” research experiences

- The concrete products:

- Number of posters

- Any submitted or accepted papers

- Defined responsibilities (data collection, analysis, first author vs co‑author)

Create a research timeline document that lists:

- Start/end dates for each project

- Key milestones (poster presented, abstract accepted, paper submitted)

- Names of mentors who can write detailed letters

This document will later feed your AMCAS activities and secondaries.

Spring (January–May)

This is execution and packaging.

From January to March you should:

- Finalize:

- At least one abstract submission

- Any manuscript that has a realistic chance of being submitted before June

- Clarify:

- How you will describe your role in each project in 700 or 1325 characters

Your layered timeline now looks like:

- Long‑term project:

- Story spanning 2–3 years

- Demonstrates commitment, growth, and depth

- Ideally yields at least a poster and a submitted paper (accepted is nice but not essential)

- Short‑term projects:

- 2–6 discrete experiences

- Several posters, maybe a lower‑authorship publication

- Show that you can come in, learn quickly, and deliver

By April:

- Draft your research activity descriptions

- Ask mentors for letters while the details are fresh

Early Medical School (M1): Resetting the Timeline

If you are reading this as an incoming M1, your clock resets, but the logic remains.

M1 Fall–Spring:

- At this point you should:

- Sample 2–3 research domains (clinical, basic science, medical education, global health)

- Choose one primary mentor by spring

- Layer:

- One long‑term project that can carry into residency applications

- One short‑term summer project that yields an early poster by M2

The structure mirrors premed:

- Year 1: Foundation + 1 lab

- Year 2: Long‑term + short‑term stack

- Year 3–4: Harvest outputs and package for ERAS

How to Decide: Short‑Term vs Long‑Term at Any Given Moment

At any point in undergrad or medical school, ask three questions:

- Time to visible output?

- Short‑term: 2–12 weeks

- Long‑term: 6–36 months

- Depth of involvement and learning?

- Short‑term: broad exposure, shallow depth

- Long‑term: focused, deep expertise

- Application timeline alignment?

- If you are ≤ 9 months from submitting applications:

- Prioritize finishing and polishing existing work

- Only start short‑term projects with clear deadlines and outputs

- If you are ≤ 9 months from submitting applications:

General pattern:

- Early years: bias slightly toward long‑term relationships, sprinkled with one short‑term project per semester or summer.

- Mid years: balanced layering with 1 major long‑term + 1 ongoing short‑term.

- Application year: finish and package; short‑term only when guaranteed to conclude in time.

Practical Scheduling Template: A Layered Week

For a typical heavy semester (e.g., sophomore spring or junior fall):

- Long‑Term Project (5–7 hrs/week):

- 2 × 2‑hour blocks for data collection or coding

- 1 × 1–2‑hour block for reading and analysis

- Short‑Term Project (3–4 hrs/week during active phase):

- 2 × 1.5–2‑hour blocks dedicated to a specific deliverable (poster draft, coding run, literature table)

Anchor these blocks like classes. Protect them from getting eaten by random meetings.

FAQ

1. What if my long‑term project fails or never leads to a publication before I apply?

At that point you should emphasize three things: continuity, responsibility, and reflection. Admissions committees care about depth and growth as much as they care about PubMed entries. Show that you stayed with a project over multiple semesters, took on increasingly complex tasks, and can articulate why the question mattered and what you learned about research design, bias, and limitations. Use your short‑term projects and posters to demonstrate that you can also bring work to completion, even if your main project’s final paper lands after submission.

2. How many research projects should I have going at once as a premed?

As a rule of thumb, during active coursework semesters you should maintain one primary long‑term project and at most one genuinely active short‑term project at any given time. During lighter periods (summer, January term), you can temporarily add one extra short‑term project if it has a very clear timeline and endpoint. More than that usually dilutes your impact and makes it harder to tell a coherent story on your application. The key is not raw count, but whether each project has a defined role on your layered timeline: foundation, short‑term output, or long‑term narrative.