Medical research is one of the most powerful ways to shape the future of Healthcare while strengthening your own training and career. Whether you are a premed student, medical student, resident, or early-career physician, learning how to engage in research will sharpen your clinical reasoning, improve patient care, and significantly enhance your residency or fellowship application.

This expanded step-by-step guide walks you through how to get started in Medical Research—from clarifying your interests and finding Mentorship to building concrete Research Skills and successfully Publishing and presenting your work.

Understanding the Value of Medical Research in Your Training

Engaging in medical research is more than just “checking a box” for your CV. It is a structured way to learn how new knowledge is generated, how evidence translates into practice, and how to ask and answer meaningful clinical questions.

Why research matters for medical students and residents

- Deepens clinical understanding: Research forces you to interrogate the “why” behind guidelines and treatment decisions, making you a more thoughtful clinician.

- Strengthens residency and fellowship applications: Programs value applicants who demonstrate curiosity, persistence, and scholarly productivity.

- Builds transferable skills: Critical appraisal, data analysis, scientific writing, and project management are useful in any medical career path.

- Expands your professional network: Research connects you with faculty, collaborators, and Mentors across departments and even institutions.

- Opens doors to leadership and academic roles: Research experience is often a prerequisite for academic medicine, quality improvement leadership, and policy roles.

Regardless of whether you envision a long-term research career, having a solid foundation in Research Skills will make you a better clinician, educator, and leader.

Step 1: Clarify and Focus Your Research Interests

Before jumping into a lab or signing onto a project, you need a sense of what genuinely interests you. Focused curiosity will make you more persistent and productive.

Reflect on your clinical and scientific interests

Ask yourself:

- Which clinical rotations or pre-clinical courses captured your attention the most?

- Do you enjoy understanding mechanisms of disease (basic or translational science), or are you more drawn to patient outcomes and health systems (clinical, epidemiology, or health services research)?

- Are there specific diseases, populations, or health disparities that you feel passionate about?

- Do you prefer working at the bench, at the bedside, or with big data?

You don’t need a perfectly defined topic, but you should have a general direction like:

- “I’m interested in cardiovascular risk in young adults.”

- “I want to study disparities in cancer screening.”

- “I’m drawn to neuroimaging in dementia.”

Use the literature to refine your interests

Reading strategically is one of the fastest ways to clarify what excites you and where the gaps are.

- Start with high-impact general journals:

The New England Journal of Medicine, JAMA, The Lancet, BMJ. - Then move to specialty journals:

For example, Circulation (cardiology), Blood (hematology), Gastroenterology (GI), etc. - Read with purpose:

- What question is each paper asking?

- How did they design the study to answer it?

- What limitations did they acknowledge?

Keep a simple document or spreadsheet where you jot down:

- Topics that repeatedly interest you

- Questions that the papers raise but don’t fully answer

- Potential ideas for future projects

Learn from real-world exposure

Outside of journals, you can discover research questions from:

- Clinical encounters: Notice recurring patterns or clinical dilemmas during shadowing or clerkships.

- Conferences and grand rounds: Listen for phrases like “we don’t yet know” or “further research is needed.”

- Quality or systems issues: Long wait times, readmission patterns, medication errors, or inequities in care are all researchable topics.

As your exposure grows, your interests will naturally narrow into more focused, feasible questions.

Step 2: Find the Right Research Mentor and Environment

Mentorship is one of the most important predictors of success in medical research. A supportive Mentor can help you choose feasible projects, build your skills, and navigate challenges.

What to look for in a research mentor

An effective research mentor often has:

- Active projects in your area of interest

- A track record of publishing and presenting

- Experience mentoring students or residents

- A communication style that matches your needs (supportive, responsive, clear)

- Reasonable expectations regarding time commitment and authorship

If possible, talk to other students or residents who have worked with that mentor to learn about their style and expectations.

How to identify potential mentors

Use multiple pathways:

Institutional websites:

- Browse department pages and faculty profiles.

- Look for “Research Interests,” “Publications,” or “Lab/Research Group” sections.

PubMed and Google Scholar:

- Search for your institution plus your topic of interest (e.g., “University X + sepsis outcomes”).

- Note authors who frequently publish in that area.

Conferences and seminars:

- Pay attention to faculty who present on topics that interest you.

- Introduce yourself briefly after talks and ask if they work with students or residents.

Peer recommendations:

- Ask senior students, residents, or fellows: “Who is great to work with for research in [field]?”

Crafting an effective outreach email

When contacting a potential mentor:

- Use a clear subject line:

“Medical student interested in joining your [field] research team” - Briefly introduce yourself:

Year, program, and any relevant background. - Highlight your interest:

Reference a specific paper or project of theirs that you found compelling. - State what you are seeking:

“I am hoping to gain experience in clinical research and would love to discuss how I might contribute to your ongoing projects.” - Be realistic about time:

Estimate your weekly availability honestly. - Attach a one-page CV and, if applicable, a transcript.

Example closing:

“Would it be possible to meet for 15–20 minutes in the coming weeks to discuss potential opportunities and how I could contribute?”

Prompt, respectful communication sets the tone for a strong mentoring relationship.

Setting expectations early

Once a mentor invites you to join a project:

- Clarify your role (data collection, chart review, analysis, writing, etc.).

- Discuss timeline and milestones (e.g., abstract by July, manuscript draft by October).

- Ask about authorship expectations and who will lead the project.

- Confirm meeting frequency (weekly, bi-weekly, monthly).

Having a shared understanding from the beginning prevents frustration later.

Step 3: Join and Contribute to Research Projects

After identifying your interests and securing Mentorship, your goal is to meaningfully engage in ongoing or new projects.

Entry points into medical research

Depending on your level and schedule, consider:

- Research assistant or volunteer roles:

Help with data collection, chart review, recruitment, or basic lab work. - Summer or dedicated research blocks:

Intensive research experiences during summer (premed/early med school) or a research year can jump-start your portfolio. - Formal research programs and scholarships:

- NIH Summer Internship Program

- Medical school-specific scholarly concentrations

- Foundation-funded student research awards

Ask your school’s research office or student affairs office about structured opportunities at your institution.

Choose projects that are feasible for your stage

For most premeds and early medical students, ideal first projects are:

- Retrospective chart reviews

- Case reports or small case series

- Systematic or scoping reviews

- Quality improvement (QI) projects

- Survey-based studies

These are typically lower cost, more flexible in timing, and less dependent on lengthy patient follow-up compared with large prospective clinical trials.

How to be a high-value team member

Your reputation early on will strongly influence the opportunities you receive later. Aim to:

- Show up consistently and be reliable about deadlines.

- Ask clarifying questions early rather than making assumptions.

- Document your work carefully (data dictionaries, version control for documents).

- Offer to help with “unexciting” tasks (reference formatting, data cleaning)—they are essential and appreciated.

- Communicate proactively when you are stuck or when your schedule changes.

Demonstrating professionalism and follow-through will often lead your mentor to offer you more substantive roles, including first-author opportunities.

Step 4: Build Core Research Skills in Methodology, Analysis, and Ethics

Strong Research Skills are what transform you from a helper into a true collaborator. Focus on the foundations: methodology, statistics, and ethics.

Understanding basic research designs

Learn the strengths and limitations of major study types:

- Observational studies

- Cross-sectional (snapshot at one time point)

- Case-control (compare those with vs. without an outcome)

- Cohort (follow exposed vs. unexposed over time)

- Interventional studies

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

- Cluster-randomized or pragmatic trials

- Qualitative studies

- Interviews, focus groups, thematic analysis

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- Synthesize existing evidence to answer focused questions

Even a basic understanding will help you design feasible projects and critically read the literature.

Getting started with statistics and data analysis

You do not need to become a statistician, but you should:

- Recognize commonly used tests (t-test, chi-square, ANOVA, regression).

- Understand concepts like p-values, confidence intervals, and effect sizes.

- Learn to use at least one statistical software platform:

- R (free, powerful, widely used)

- SPSS, Stata, or SAS (often available through institutions)

- Excel for simple descriptive statistics and data visualization

Free or low-cost learning resources:

- Coursera, edX, or university offerings in biostatistics or epidemiology

- YouTube tutorials on R or SPSS basics

- Institutional workshops from your biostatistics or public health department

Mastering research ethics and regulatory requirements

When working with human participants or identifiable data, you must understand and follow ethical principles and regulations:

- Foundational principles (Belmont Report):

- Respect for persons

- Beneficence

- Justice

- IRB approval (Institutional Review Board):

- Most human-subject projects require IRB review before data collection.

- Your mentor or department usually handles the protocol, but you should read and understand it.

- Informed consent, confidentiality, and data security:

- Use secure data storage (institutional servers, encrypted drives).

- De-identify data whenever possible.

Complete standard online training such as CITI (Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative) if your institution requires it.

Additional skill-building opportunities

Look for:

- Workshops on grant writing, data management, or survey design

- Short courses in clinical trial design or implementation science

- Journal clubs where you can practice critical appraisal

Each new skill makes you more independent and valuable in future research endeavors.

Step 5: Write, Publish, and Present Your Research

Generating results is only half the work; you also need to communicate your findings clearly and professionally to the wider medical community.

Writing a strong research manuscript

Most original research papers follow the IMRaD structure:

- Introduction

- What is known and unknown?

- What specific question or hypothesis are you addressing?

- Methods

- Study design, setting, and population

- Inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Data collection procedures

- Definitions of variables and outcomes

- Statistical analysis plan

- Results

- Participant flow and baseline characteristics

- Main outcomes (with tables/figures)

- Secondary or exploratory analyses

- Discussion

- Interpretation of findings

- Comparison with prior literature

- Strengths and limitations

- Clinical or research implications

- Future directions

Collaborate closely with your mentor and co-authors during drafting. Tools like reference managers (e.g., Zotero, Mendeley, EndNote) will streamline your citation process.

Choosing the right journal or conference

Consider:

- Scope and audience: Is your work clinical, basic science, educational, or quality improvement?

- Study type: Some journals specialize in case reports, QI, or trainee-authored work.

- Impact factor and reach: Higher-impact journals are more competitive; balance ambition with realism.

- Open access vs. subscription-based: Some funders require open-access publication, but this may involve article processing charges (often waivable or discounted for trainees).

Your mentor’s experience with particular journals is invaluable here.

Navigating the peer review and revision process

Once submitted:

- Your paper will undergo editorial screening and peer review.

- Outcomes typically are:

- Accept (rare on first submission)

- Minor revision

- Major revision

- Reject (with or without resubmission option)

Use feedback constructively:

- Address comments point-by-point in a separate response document.

- Be polite and professional, even when you disagree—justify your position with data or references.

- If rejected, work with your mentor to refine the manuscript and resubmit to another appropriate journal.

Rejection is a normal part of research life; resilience and persistence are key.

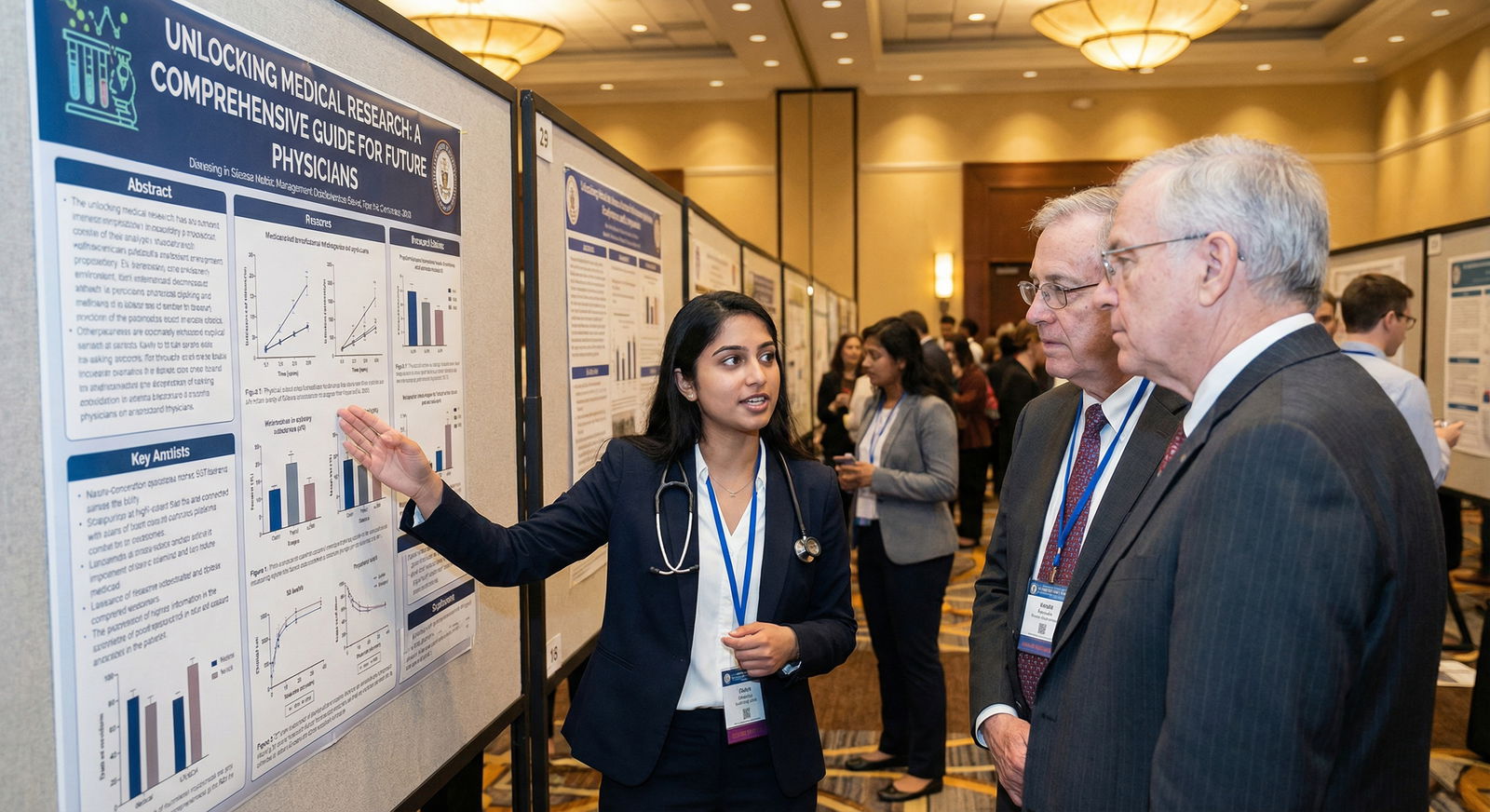

Presenting your work: posters and oral talks

Dissemination isn’t limited to journals. Conferences provide powerful Networking and feedback opportunities.

Poster presentations:

- Use clear headings and minimal text.

- Highlight a simple, visual story (problem → method → main results → implications).

- Practice a 1–2 minute “elevator pitch” of your work.

Oral presentations:

- Structure your talk similarly to your paper but with fewer details.

- Use clean, readable slides with minimal text and clear figures.

- Rehearse multiple times, including with someone unfamiliar with the topic.

Presentations demonstrate your communication skills and visibility as a young investigator.

Step 6: Network Strategically and Build a Sustainable Research Path

A career in Medical Research—or even consistent scholarly activity—requires more than individual projects. It’s about cultivating a community and a trajectory.

Using research to build your professional network

- Talk to people at conferences:

Introduce yourself to speakers or authors whose work you admire. Mention a specific point from their talk or paper. - Stay connected with collaborators:

Periodically update past mentors about your progress and current projects. - Join professional societies:

Many specialties have student and resident sections with research opportunities, mentorship programs, and travel grants.

Active networking helps you find future collaborations, letters of recommendation, and training positions.

Reflecting and planning your next steps

After each project, ask:

- What did I enjoy most (design, data, analysis, writing, presenting)?

- Which skills did I gain, and which do I still need to build?

- Do I want to deepen my expertise in this area or explore a new topic?

Over time, you may naturally develop a research niche, such as:

- Cardiovascular risk management in underserved populations

- Medical education interventions for clinical reasoning

- Outcomes of minimally invasive surgical approaches

Having a coherent theme is especially valuable when applying for competitive residencies, fellowships, or academic positions.

Long-term options to advance your research career

If you find that medical research energizes you, consider:

- Dedicated research years during medical school or residency

- Fellowships with a strong research component

- Graduate degrees:

- Master of Public Health (MPH)

- Master of Science (MS) in Clinical Investigation, Epidemiology, or Biostatistics

- PhD for those committed to extensive research careers

- K-awards or other career development grants in early faculty years

Even if you ultimately focus on clinical practice, having rigorous research training will position you as an evidence-based leader in your field.

FAQ: Common Questions About Getting Started in Medical Research

1. I have no prior research experience. Can I still get involved as a premed or early medical student?

Yes. Many mentors are happy to work with motivated beginners. You might start with simpler tasks—literature review, data entry, chart abstraction, or helping with a case report—while you learn core Research Skills. Be upfront about your level and emphasize your willingness to learn and your reliability. Over time, you can progress to more complex roles and even first-author projects.

2. How many research projects or publications do I need for residency?

There is no universal number. Expectations vary by specialty and program competitiveness:

- Highly competitive fields (e.g., dermatology, plastic surgery, radiation oncology) often expect multiple publications or presentations.

- Moderately competitive fields (e.g., internal medicine, pediatrics) value a track record of scholarly engagement, which may include a handful of posters, abstracts, or manuscripts.

- Less research-focused specialties may view any research as a plus but not a requirement.

Programs care not only about quantity but also about depth, continuity, and your role in the work. A few well-executed projects where you can clearly articulate your contributions often matter more than a long list of superficial involvements.

3. How do I balance research with classes, clinical duties, and board preparation?

Time management and expectation-setting are crucial:

- Start with one primary project rather than many small, scattered commitments.

- Agree on a realistic weekly time commitment with your mentor (e.g., 3–5 hours/week).

- Use small time blocks (30–60 minutes) effectively for tasks like reading articles or revising drafts.

- During intense exam or clinical periods, communicate early with your mentor and adjust deadlines if needed.

Viewing research as a long-term investment rather than a short sprint will help you pace yourself and avoid burnout.

4. What if my project never gets published? Was it a waste of time?

Not at all. While Publication is an important goal, especially for career advancement, each project teaches you:

- How to ask better questions and design stronger studies

- How to manage data, think critically, and collaborate

- How to navigate challenges and setbacks

If a study doesn’t reach a journal, consider alternative forms of dissemination:

- Poster or oral presentation at a local or regional conference

- Institutional research day

- Departmental grand rounds or seminars

Reflect on what you learned and use that insight to design more feasible, impactful projects next time.

5. How can I find funding or support for my research?

Many projects—especially retrospective chart reviews, surveys, and educational research—require little to no external funding. For projects with financial needs (e.g., lab reagents, participant incentives, software licenses):

- Explore internal institutional funds (student research awards, departmental pilot grants).

- Look for national or specialty-specific grants aimed at trainees.

- Ask your mentor about existing grants that might cover your project.

- Consider pairing with a senior investigator who already has funding in your area of interest.

Learning basic grant-writing skills early can be a major asset later in your career.

Engaging in Medical Research is one of the most rewarding ways to deepen your understanding of healthcare, develop critical professional skills, and shape your future career. By clarifying your interests, seeking strong Mentorship, intentionally developing Research Skills, and sharing your findings through Publishing and presentations, you can build a meaningful and sustainable research journey—starting from premed or medical school and continuing throughout your career in medicine.