Studying Abroad as a Pre‑Med: When It Makes Sense and How to Plan It

Is a semester in Spain or a year in London going to boost your med school application—or quietly wreck your prerequisites and delay your timeline?

You are not just picking between Paris and Prague. You are deciding whether you can leave your home campus for months, keep your GPA intact, finish all pre‑med requirements, stay on track for the MCAT, and still look like a serious future physician to admissions committees. This is where a lot of pre‑meds miscalculate.

(See also: Managing Pre‑Med Demands While Working a Part‑Time Job for more on balancing responsibilities.)

Let’s walk through this like a real situation, not a brochure.

1. When Studying Abroad Makes Sense as a Pre‑Med

Studying abroad is not automatically a plus or a minus. It depends heavily on:

- When you go

- What you study

- How it fits into your overall academic and application timeline

Here are the situations where it tends to make sense.

a. You have your core science sequence under control

If you’re a typical 4‑year pre‑med planning a traditional path (apply after junior year, start med school right after graduation), the safest windows are:

- Spring of 2nd year (sophomore spring)

- Fall of 3rd year (junior fall) if you plan to apply after a gap year

- Summer programs between 1st–2nd year or 2nd–3rd year

It makes sense when:

- You’ll have completed at least one full year of:

- General chemistry

- General biology

- And preferably your first semester of organic chemistry

Why? Because these are courses where:

- Med schools care about letter grades

- MCAT content is heavily based

- You want consistent instruction without credit transfer weirdness

If you’re thinking: “I’ll just take orgo abroad, it’s still chemistry.” Stop. That is exactly where students get burned.

b. You’re not using study abroad to “run away” from weak academics

Study abroad can make sense if:

- Your GPA is stable and trending up

- You’re not trying to escape a rough semester by hiding in pass/fail classes abroad

- You’ve already shown you can handle heavy science loads at your home institution

If you’re struggling with C’s in gen chem and physics, then planning to leave your support system, tutoring, and familiar professors might not be the best next move—unless the abroad semester is specifically structured to support you academically (rare, but possible in highly organized programs).

c. The abroad program adds something clearly meaningful

Med schools do not care that you drank espresso in Rome. They care if:

- You advanced your language skills in a language you might use clinically (Spanish, Mandarin, Arabic, etc.)

- You studied public health, global health systems, or health policy with real rigor

- You did serious research or a structured, supervised global health program (not shadowing in ways that would be illegal in the U.S.)

- You grew in ways you can articulate: independence, cross‑cultural communication, adaptability

If the program is mostly tourism and light academics, it still might be good for you as a person—but it’s not a strategic pre‑med move. That is fine as long as you’re honest with yourself about that.

d. You have a realistic MCAT and application timeline

Studying abroad makes sense when it does not:

- Cramp your MCAT prep into an impossible window

- Collide with your primary application summer

- Block you from doing clinical volunteering or research for long stretches without a plan to restart

Example where it makes sense:

- You go abroad spring of sophomore year

- You take MCAT in late spring or early summer of junior year

- You apply after junior year (or after a gap year) with a full year of clinical exposure before and after your abroad term

Example where it does not:

- You go abroad spring of junior year

- You try to self‑study MCAT alone in a different time zone, with limited resources

- You plan to test in May/June of that same year

That second scenario is how people end up with below‑target MCATs and “I’ll just reapply” plans they never meant to have.

2. When Studying Abroad Is Risky (or Just a Bad Fit)

Here’s when you should pause hard before signing any study abroad forms.

a. You’re planning to take key pre‑reqs abroad

Red flags:

- General chemistry, biology, physics, or organic chemistry abroad

- Especially if:

- The course is pass/fail

- The course number doesn’t map cleanly to your home university’s pre‑med sequence

- It’s taught in a different system (e.g., British system where exams are 100% of grade)

Many med schools either:

- Don’t accept foreign coursework for prerequisites

- Or accept it only if it appears as graded credit on a U.S. or Canadian transcript

That’s not just “the med school might not like it.” Sometimes they literally won’t count it.

If your advisor cannot clearly say, in writing, “Yes, our pre‑health committee is fine with you taking X course abroad to fulfill Y requirement,” assume it’s risky.

b. Your GPA is fragile

If you’re hovering around:

- 3.3–3.5 overall or science GPA and trying to rise

- Or you’ve had a rough semester (C’s in orgo or physics)

Then adding:

- A new environment

- Different grading systems

- Potential credit transfer unpredictability

might hurt more than it helps. Especially in systems where:

- Grades are heavily exam‑weighted

- Curves are harsh

- Local students are used to a completely different style of teaching/testing

In that situation, a summer abroad might be safer than a full semester, or you might prioritize your GPA now and plan for global experiences in med school or residency.

c. You need consistent clinical or research continuity

If you’re about to start:

- A 1‑year clinical volunteering commitment at a hospital

- A lab position that could turn into a publication or strong letter

and you leave after two months to go abroad for a semester, you may be trading away a much more powerful application asset.

Continuity matters to admissions committees. Someone who:

- Volunteered in an ED for two years

- Or worked in the same research lab for 18 months

generally looks stronger than someone with eight short, scattered experiences—even if one of them was abroad.

3. Choosing the Right Time in Your Pre‑Med Timeline

Let’s break timing down by year and situation.

Freshman year

Should you go abroad as a freshman? Usually not for a full semester if you’re pre‑med.

Why:

- You’re still adjusting to college academics

- You’re just starting your science sequence

- You haven’t had time to establish a GPA foundation

Better options:

- Short summer program after freshman year that doesn’t involve pre‑req sciences

- Language or culture‑focused programs that are clearly electives

Sophomore year

This is often the sweet spot, especially spring semester.

Works well if:

- You did gen chem and/or gen bio in freshman year

- You’re not using abroad courses for pre‑med core requirements

- You’re planning on:

- MCAT in junior spring or summer

- Application after junior year or after a gap year

Common mistake: trying to cram orgo I in fall, studying abroad in spring with no science, then taking orgo II junior fall. That break can make orgo II brutal.

Better sequence example:

- Freshman: Gen chem + bio

- Sophomore fall: Orgo I + physics I

- Sophomore spring abroad: mostly non‑science or lighter science that doesn’t substitute for cores

- Junior year: Orgo II, physics II, maybe biochem

Junior year

If you’re applying without a gap year, junior spring abroad is very tough to pull off.

Reasons:

- MCAT timing

- Letters of recommendation

- Clinical work right before application

- Being reachable for interviews/committee processes

Junior fall abroad can work better if you:

- Plan for a gap year

- Take MCAT at the end of junior year or during the gap year

If you insist on applying straight through and going abroad junior year, you’ll need an extremely detailed plan (we’ll get to how to build one), including MCAT prep before you leave or over the previous summer.

Senior year

If you’re on a gap‑year or non‑traditional timeline, senior year abroad can actually be safer.

Examples:

- You already applied and are taking a gap year: go abroad during that year

- You apply at the end of senior year: go abroad senior fall, apply after graduating

The key: make sure med schools can still reach you for interviews or secondaries if you’re abroad during your application year.

4. How to Vet a Study Abroad Program as a Pre‑Med

Once you’ve decided “Maybe this actually could work,” you need to interrogate the program like a future physician assessing a treatment plan.

Step 1: Verify how credits show up

Ask your home school:

- Will the classes appear as:

- Letter grades on your home transcript?

- Pass/fail only?

- Transfer credits with no grades?

AMCAS (for MD schools) generally requires:

- Letter grades from U.S. and Canadian institutions

- Foreign grades often do not factor into GPA, but credits may still appear

- Study abroad through a U.S. institution (e.g., Duke in Madrid, Cornell in Rome) often counts fully like home coursework

Ideal for pre‑reqs: taken at a U.S. or Canadian institution, letter graded, clearly equivalent.

Ideal for abroad electives: can be pass/fail or transfer, as long as you’re not relying on them for critical GPA padding.

Step 2: Check med school and pre‑health office policies

You need answers (in writing if possible) to:

- “Will X course abroad fulfill our biology/chemistry/physics/English requirement?”

- “Do we have alumni who did this exact program and successfully applied to med school?”

- “Does our pre‑health committee have any concerns about this specific program for pre‑meds?”

If your pre‑health office hesitates or says, “We usually recommend against taking core sciences abroad,” that’s a serious signal.

Step 3: Evaluate academic structure

Ask about:

- Class size and structure (lecture, tutorials, labs)

- Grading breakdown (exam‑heavy? participation? essays?)

- Language of instruction and your proficiency

For heavy science terms like “signal transduction” or “ketogenesis,” even strong conversational language skills might not be enough. This can hurt your grades and your understanding.

If you’re doing any science in another language, be sure you can handle scientific vocabulary. If not, choose non‑science courses abroad.

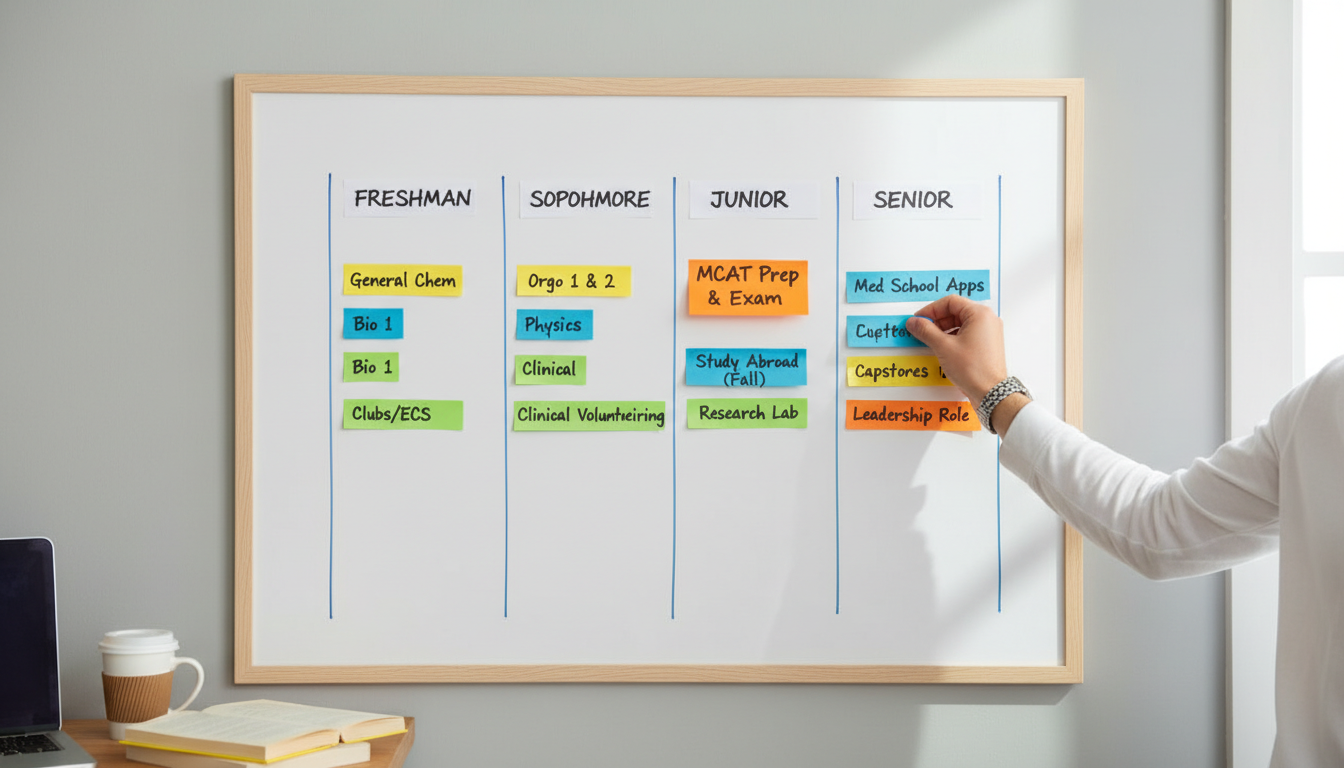

5. Building a Concrete 4‑Year Plan that Includes Study Abroad

Here’s how to actually map this in a way med schools will respect.

Step 1: Lay out the non‑negotiables

You need:

- Full sequence of:

- General chemistry with lab

- General biology with lab

- Physics with lab

- Organic chemistry with lab

- Biochemistry (strongly recommended)

- MCAT timing

- Minimum 1–2 years of:

- Clinical exposure

- Some volunteering or community service

- Ideally research or at least one longitudinal non‑clinical activity

Write these on a year‑by‑year grid.

Step 2: Choose your abroad window, then fit everything around it

Example: You decide on sophomore spring abroad.

Work backward and forward:

- Freshman:

- Fall: Gen chem I + bio I

- Spring: Gen chem II + bio II

- Sophomore:

- Fall: Orgo I + physics I

- Spring abroad: language and electives, maybe public health, no core science

- Junior:

- Fall: Orgo II + physics II

- Spring: Biochem + MCAT prep, test in late spring or early summer

- Summer after junior: Apply to med school

Then layer:

- Clinical involvement: start freshman or sophomore year, pause while abroad, resume after return

- Research: maybe start sophomore fall, pause abroad, ramp up junior year

Step 3: Plan for letters and continuity

Before you leave:

- Establish relationships with:

- 1–2 science professors who can write letters later

- Your PI (if you’re in a lab)

- Volunteer supervisors

Tell them:

- When you’ll be abroad

- That you hope to ask for letters when you return or before you apply

Keep in touch via email while abroad so the relationship doesn’t go cold.

6. MCAT Preparation and Studying Abroad

This is where pre‑meds most often misjudge.

If you go abroad sophomore year

Safer. Your MCAT is likely:

- Late junior year

- Or even during a gap year

Plan:

- Use sophomore year to nail foundational sciences

- Use junior year on campus for content review and practice exams

- Do not rely on heavy MCAT content review while abroad unless the program’s structure and your schedule are very light

If you go abroad junior year

This becomes much more delicate.

If you’re applying:

- After a gap year:

- Junior year abroad is more manageable

- You can do MCAT content review junior summer + fall of senior year

- Without a gap year:

- You’d need most science content done by end of sophomore year

- Likely start MCAT prep before leaving or while abroad

- Test planning becomes tight and stressful

Be brutally honest about:

- Your self‑discipline abroad

- Access to quiet study space and good internet

- Whether you want your “abroad semester” to feel like MCAT boot camp (many regret this setup)

For most students, the best combo is:

- Study abroad a year before serious MCAT prep begins

- Or plan MCAT after your abroad term, with a long enough runway

7. Clinical, Volunteering, and Research While or After Abroad

You won’t be doing U.S.-style clinical volunteering in most foreign systems, and you should not be providing hands‑on care as a student in ways that would be prohibited at home.

Think of abroad like this:

- Before abroad: build a base of clinical and service experience

- During abroad: lean into cultural and language learning, structured programs, and reflection

- After abroad: return and re‑establish or deepen long‑term clinical and research commitments

If your study abroad includes “shadowing” or “clinic visits,” make sure they are:

- Observational only

- Ethically structured

- Not you doing procedures, injections, or anything you’re not trained/licensed to do

Med schools know about sketchy “global health mission trips” where pre‑meds do things far outside their scope. You do not want your abroad story to raise red flags.

8. How to Talk About Study Abroad on Your Application

When it comes time to write about it, you need to be able to answer:

- Why did you choose to go abroad, given how busy pre‑med is?

- What did you learn that’s relevant to being a physician?

- How did you handle challenges (language barriers, academic differences, being far from home)?

- Did you maintain or strengthen your commitment to medicine afterward?

Weak framing:

“I always wanted to travel, so I went to Florence. I learned to be independent.”

Stronger framing:

“I spent a semester in Santiago, Chile, where I completed upper‑division Spanish and a public health course examining rural health access. I lived with a host family that relied on the public system, which forced me to confront how language and geography shape care. When I returned, I began volunteering at a local free clinic serving Spanish‑speaking patients, using the language skills and cultural perspective I developed abroad.”

Notice the difference:

- Concrete

- Connects abroad to later actions

- Clearly relevant to patient care and health systems

If your abroad experience is mostly personal growth, that is still fine. Just be ready to connect:

- Cultural humility

- Communication across differences

- Adaptability

to your future role as a physician.

9. Decision Checklist: Should You Actually Go?

Before you submit any applications or deposits, ask yourself:

Is there a clear semester where:

- My core sciences are not interrupted?

- My MCAT timeline stays sane?

- My GPA is unlikely to suffer?

Has my pre‑health advisor:

- Reviewed my full 4‑year plan with study abroad included?

- Flagged any course or timing issues?

Does this program:

- Offer academic rigor I can handle?

- Add something meaningful (language, public health, cultural depth)?

- Avoid sketchy “medical mission” style activities?

Can I:

- Maintain or restart clinical and service experiences on return?

- Stay on track with letters, research, and other core application elements?

If you can’t confidently answer “yes” to most of those, it might be smarter to:

- Choose a shorter summer program

- Delay major travel to the gap year, med school, or residency global health electives

Core Takeaways

- Studying abroad as a pre‑med can work well if it’s planned around your core sciences, GPA, MCAT, and clinical/research continuity—not jammed in randomly.

- The safest academic move is: take your main pre‑reqs at your home (or U.S./Canadian) institution, use abroad time for language, public/global health, and electives.

- If you decide to go, build a detailed 4‑year plan on paper, run it through your pre‑health office, and be sure you can explain later not just where you went—but why it made you a better future physician.