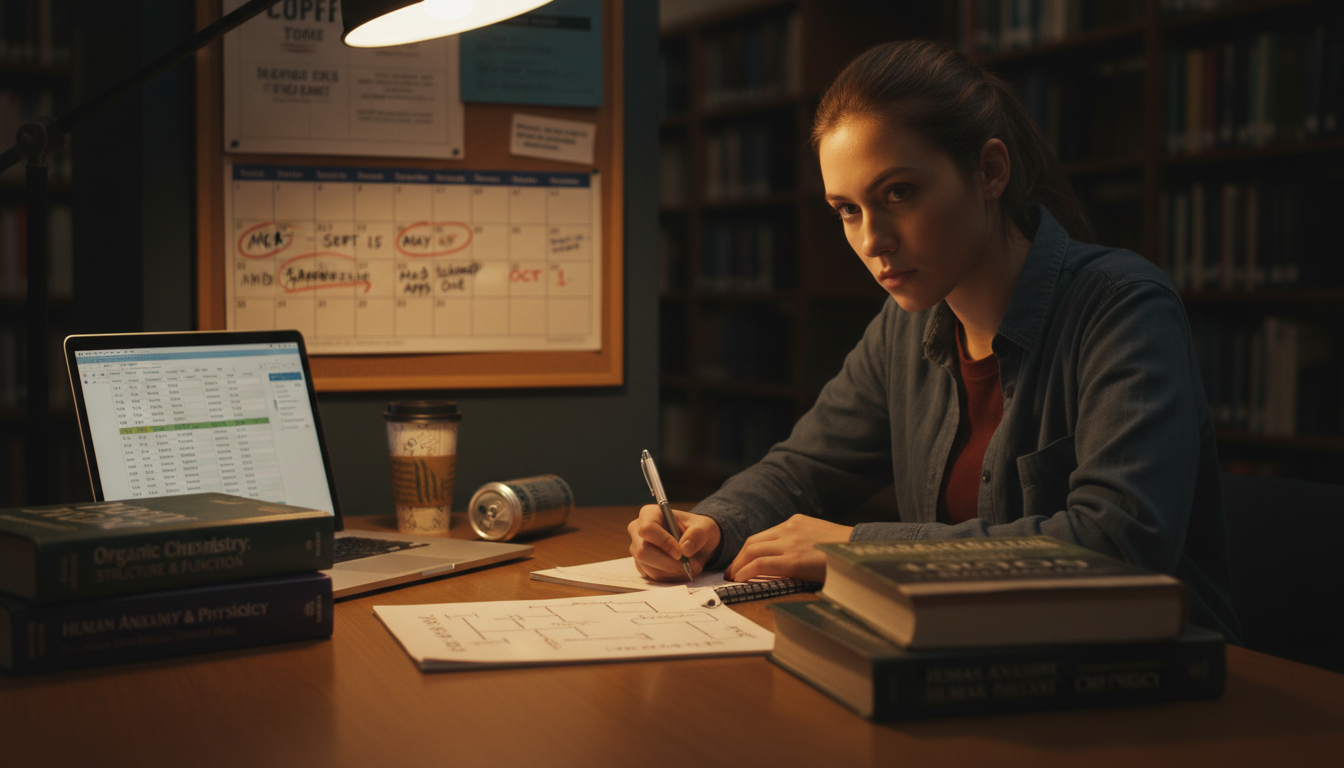

It is the middle of your junior year. Your friends are locking in job offers, your advisor thinks you are headed for consulting or grad school, and you just realized you actually want to go to medical school.

You open a med school website and see the words: “One year of biology, one year of chemistry, one year of organic chemistry, one year of physics…”

You have…maybe one of those.

This feels late. Maybe even impossible.

(See also: How to Build Strong Premed Letters When You’re at a Huge University for insights on securing strong recommendations.)

It is not.

You are not going to brute-force your way through this by “working hard” and “staying motivated.” You need a systematic catch‑up plan that:

- Fits your remaining semesters and summers

- Covers all prerequisites

- Leaves time for MCAT prep

- Builds credible clinical and extracurricular experience

- Keeps GPA damage to a minimum

Below is a concrete, step‑by‑step blueprint you can adapt, whether you are:

- A late junior changing majors

- A senior about to graduate

- Or a recent graduate realizing medicine is the right path

Step 1: Get Your Timeline and Constraints on Paper

Before you touch course catalogs or MCAT books, define the playing field.

1. Identify your current point:

- Year in school:

- Sophomore / junior / senior / recent graduate

- Current major and credits completed

- Science background so far:

- General biology?

- General chemistry?

- Any lab sciences?

- Math / statistics?

2. Decide your target application cycle

You apply roughly 15 months before you start medical school. For example:

- Want to start med school: August 2028

- You will apply: June 2027

- MCAT ideally taken: Jan–May 2027 (or earlier)

- Core prereqs ideally done by: end of 2026

If you are already a late junior with few sciences, trying to apply immediately after graduation usually means:

- Heavy science load

- Weak MCAT prep window

- Little time for shadowing / clinical experience

For many late pre‑meds, the realistic path is:

- 1–2 “glide years” (years between graduation and starting med school)

- Use them for post‑bacc coursework, MCAT, clinical work, and strengthening your application

You are not “behind” if you start medical school at 24–26. That is extremely common.

3. Hard constraints to list:

Write these down:

- When you graduate (fixed by your college)

- Maximum credits/semester you can handle without crashing (often 14–16 if adding labs)

- Financial constraints:

- Can you afford a post‑bacc?

- Do you need to work during school or summers?

- Non‑negotiable responsibilities:

- Family care

- Job you cannot quit yet

Once your constraints are explicit, you can design around them rather than pretending they do not exist.

Step 2: Map Required Prerequisites vs. What You Actually Have

Most U.S. MD and DO schools require some version of:

- Biology

- 2 semesters with lab (Intro Bio I & II)

- General (Inorganic) Chemistry

- 2 semesters with lab

- Organic Chemistry

- 2 semesters with lab (some schools accept 1 orgo + 1 biochem)

- Physics

- 2 semesters with lab (algebra‑based is usually fine)

- Biochemistry

- 1 semester (increasingly expected, even if not formally “required”)

- Math

- 1 semester of calculus and/or statistics (varies by school)

- English / Writing

- 2 semesters of writing‑intensive courses (not always labeled “English”)

Action: Build a simple 3‑column chart:

| Subject | Typical Requirement | Completed? (Y/N + details) |

|---|---|---|

| Biology | 2 sem + lab | |

| General Chem | 2 sem + lab | |

| Organic Chem | 2 sem + lab | |

| Physics | 2 sem + lab | |

| Biochemistry | 1 sem | |

| Math/Stats | 1–2 sem | |

| English/Writing | 2 sem |

Be brutally honest. “AP Bio in high school” usually does not count. Your med school’s website is the authority.

This chart is now your coursework gap list.

Step 3: Choose Your Structural Path: In‑College vs Post‑Bacc

You have two broad structural options:

Option A: Finish Prereqs Mostly During College

Best suited for:

- Sophomores and early juniors

- Students with room in schedule and decent academic footing

Advantages:

- Lower cost (using your undergrad tuition)

- Keeps you on a more “traditional” path

- You can apply soon after graduation if you move efficiently

Disadvantages:

- Heavy science load that can hurt GPA

- Less flexibility in timing MCAT and clinical work

Option B: Deliberately Plan on a Post‑Bacc or Extra Year

Best suited for:

- Late juniors, seniors, or recent grads with few science courses

- Those who want more time and a stronger record

Two flavors:

Formal post‑bacc program

- Structured programs (e.g., Columbia, Bryn Mawr, Goucher, some state schools)

- Advising, built‑in schedule, sometimes linkage agreements

- Can be expensive but organized

DIY / informal post‑bacc

- Take needed science courses at:

- Your current university (as non‑degree student)

- Local state university

- Community college (acceptable for some courses, but check med school preferences)

- Take needed science courses at:

Advantages:

- Cleaner science GPA reset if your earlier record is weaker

- More deliberate MCAT prep window

- Time for clinical work and meaningful volunteering

Disadvantages:

- Extra time and cost

- Requires more self‑management

If you are a late junior or senior with minimal science background, planning on at least 1 glide year and using a post‑bacc type approach is usually the safer, higher‑quality route.

Step 4: Build a Semester‑by‑Semester Catch‑Up Plan

Now we convert the gap list into an actual schedule.

General principles:

- Never overload more than 2 lab sciences in one term if your goal is strong grades.

- Stack sequential courses carefully:

- Gen Chem → Orgo → Biochem

- Intro Bio → upper‑level biology

- Reserve a clean 3–4 month block for MCAT prep with lighter coursework or during a gap/summer.

- Protect your GPA. A slower path with 3.7–3.9 science GPA is better than a rushed 3.1.

Example Scenarios

Scenario 1: Late Junior with Some Science

You are a junior in Spring 2025. You have:

- Gen Bio I (B+), Gen Chem I (A–)

- No labs yet (they are separate courses)

- No physics, no orgo, no biochem

You decide to graduate on time and take a glide year, planning to apply June 2027 for med school start 2028.

Plan sketch:

Spring 2025 (now)

- Gen Bio II + lab

- Gen Chem II + lab

- 1–2 lighter non‑science courses

Summer 2025

- Shadowing 1–2 physicians (20–40 hours total)

- Begin light clinical volunteering (e.g., hospital volunteer 4 hrs/week)

Fall 2025 (senior year)

- Organic Chem I + lab

- Physics I + lab

- 1–2 non‑sciences

Spring 2026

- Organic Chem II + lab

- Physics II + lab

- Upper‑level biology (e.g., physiology or cell biology)

Graduate May 2026.

Summer–Fall 2026 (first glide year)

- Biochemistry (summer or fall at local/state university)

- Increase clinical work:

- EMT course and job

- Medical assistant / scribe / CNA

- Dedicated MCAT prep (see Step 6) aim for Jan–April 2027 test date

Spring 2027

- Continue clinical and volunteering

- Prepare application materials (personal statement, activities list, letters)

June 2027

- Submit primaries

This path gives you:

- Full prereq set

- Solid MCAT window

- Real clinical hours

- No insane 3‑lab semesters

Scenario 2: Senior with Almost No Science

You are a senior graduating May 2025. Major in History. Only science is one “Science for Non‑Majors” course.

Realistically, you need a 2‑year structured post‑bacc timeline.

Year 1 Post‑Grad (2025–2026):

Fall 2025:

- Gen Chem I + lab

- Bio I + lab

Spring 2026:

- Gen Chem II + lab

- Bio II + lab

Clinical exposure: start hospital volunteering 3–4 hrs/week, begin shadowing

Summer 2026:

- Physics I + lab (if offered)

- Light MCAT content preview

Year 2 (2026–2027):

Fall 2026:

- Organic Chem I + lab

- Physics II + lab

Spring 2027:

- Organic Chem II + lab

- Biochemistry

Plan MCAT for late Spring or Summer 2027, then apply June 2027 or June 2028 depending on readiness.

The specific dates will vary, but the logic stays constant: never crush yourself with excessive labs, keep upward momentum, and slot MCAT prep when core sciences are mostly done.

Step 5: Protect and Repair Your GPA Strategically

Switching late often means two things:

- You might not have a strong science foundation

- You cannot afford early stumbles in hard courses like organic chemistry

Key rules:

Start with foundation courses where you can earn A/A–.

- If your math is rusty, take precalc or a gentle intro before physics.

- Use tutoring early in any course where you score below B+ on first exam.

Avoid “hero schedules.”

Do not do:- Organic Chem I + Physics I + Cell Biology + Biochem in the same term.

That is a recipe for mediocrity at best.

- Organic Chem I + Physics I + Cell Biology + Biochem in the same term.

Use institutional resources aggressively:

- Office hours (weekly, not just before exams)

- Learning center / science tutoring

- Study groups with 2–3 serious classmates

- Old exams and practice problem sets

Consider where you take courses:

- Upper‑level sciences at your home university usually carry more weight than community college.

- Some med schools are cautious with heavy CC science loads if your 4‑year school is an option.

- That said, a strong A at a community college is much better than a C at a 4‑year.

If you have an existing low GPA:

- Focus on upward trend over time.

- A strong last 2–3 years in rigorous science courses can soften a lower freshman/sophomore GPA.

You are not just filling boxes. You are building a credible academic story: “I can handle medical school level science.”

Step 6: Plan MCAT Timing and Prep the Right Way

The MCAT is not something you glue onto the end of a brutal semester and hope for the best.

1. What content you should have completed before MCAT:

Strongly recommended before serious MCAT prep:

- Intro Biology I & II

- General Chemistry I & II

- Organic Chemistry I (and ideally II)

- Physics I & II

- Biochemistry

You can start light prep earlier, but full‑force MCAT study without biochem usually leads to reteaching yourself too much content later.

2. Ideal timing for late pre‑meds:

- Take the MCAT January–May of the year you apply.

- If you are doing a glide year, this is often after graduation or during a lighter post‑bacc term.

Examples:

- Applying June 2027 → MCAT between Jan–May 2027

- Applying June 2028 → MCAT between Aug 2027–May 2028

3. Build a prep plan (3–6 months)

A solid prep arc often looks like:

Phase 1: Content Review (8–10 weeks)

- 2–3 hours/day weekdays + 4–6 hours on one weekend day

- Use a major MCAT content set (Kaplan, Blueprint, Princeton Review, etc.)

- Make structured notes and flashcards (Anki or similar)

Phase 2: Practice‑Heavy (6–8 weeks)

- Full‑length practice exams every 1–2 weeks

- Thorough review of every question, correct or not

- Focus on CARS practice almost daily

- Identify content weak points and patch them selectively

If you are working or in classes, you may need to stretch this over more calendar months with fewer hours per week.

4. Resources to prioritize:

- AAMC official materials (full‑length tests, section banks, question packs)

- One major commercial prep series for structure

- CARS practice from multiple sources

The non‑negotiable: do not schedule the MCAT in a term where you are also taking Organic II, Physics II, and Biochem and working 20 hours/week. Something will break, usually your score.

Step 7: Build Clinical, Shadowing, and Non‑Clinical Experience Efficiently

You are late, so you need efficient, high‑yield experiences. Think of three pillars:

- Clinical exposure (you interact with patients or clinical settings)

- Shadowing (you observe physicians)

- Non‑clinical service (shows you care about people beyond medicine)

Clinical exposure options (choose 1–2 and go deep):

Hospital volunteer:

- Roles like patient transport, unit assistant, ED volunteer

- Aim: 2–4 hours/week for 1+ year; depth > sheer hours

Medical scribe (highly valued):

- Shadowing‑plus‑documentation role in clinics or EDs

- Paid, very educational about clinical reasoning

EMT:

- Requires certification course (often one semester)

- Great for hands‑on experience and responsibility

Medical assistant (MA), CNA, phlebotomist:

- Short training programs

- Direct patient care; good during glide year

As a late pre‑med, consider scribe or EMT during your glide year if you can manage the training and schedule.

Physician shadowing:

Aim for:

- 3–5 physicians

- 40–80 hours total

- Mix of fields (primary care + at least one specialty)

Shadowing is often easier to start earlier, even with a light load (e.g., 4 hours one morning every other week while in school).

Non‑clinical service:

Adcoms care whether you work with people different from yourself. Examples:

- Working with underserved populations:

- Food pantry, homeless shelter, refugee tutoring, crisis hotline

- Long‑term commitment preferred over scattered one‑offs

Key point: You do not need 10 clubs. You need a few longitudinal commitments where you show up consistently and can show growth.

Step 8: Re‑Position Your Major and Past Experience as Strengths

Switching late usually means you are not a traditional biology major who has been aiming at medicine since age 12.

That can be an asset if you frame it correctly.

1. Leverage your non‑science major

Whether you studied:

- Economics

- Philosophy

- Engineering

- Art history

You can frame:

- How it trained your thinking (e.g., ethics, quantitative reasoning, communication)

- How it changed your view of people or systems

- How those skills will transfer to medicine

Example:

A Philosophy major can talk about grappling with moral ambiguity, which maps directly to real‑world clinical decision‑making.

2. Mine your past activities

Do not throw away:

- Leadership roles in non‑medical clubs

- Research in a non‑science field

- Jobs that paid for school or supported family

- Study abroad

Connect them to:

- Resilience

- Communication

- Cultural competence

- Teamwork

The story becomes: “I developed X and Y strengths doing A, B, and C. When I realized medicine fit those strengths and values, I took concrete steps to build the scientific and clinical foundation.”

You are not “late and lost”. You are “bringing additional dimensions to the class”.

Step 9: Build Your Support Team and Information Sources

Doing this alone is harder than it needs to be. Construct a small, targeted support network.

1. Academic advisors and faculty

- Meet with your pre‑health advisor and be transparent about your timing and gaps.

- If your school’s advisor is not helpful, identify:

- A science professor you respect

- A post‑bacc or pre‑health program at a nearby institution

Bring your prereq gap chart and a draft semester‑by‑semester plan. Ask: “What would you change to make this realistic and competitive?”

2. Mentors in medicine

Try to identify:

- A physician you shadow and can occasionally ask big‑picture questions

- A resident or med student (through alumni networks)

- Someone who came to medicine non‑traditionally

Ask for specific advice, not vague mentoring. For example:

- “Given my background in sociology and my plan to do a DIY post‑bacc, what should I prioritize in my gap year to be competitive?”

3. Peer community

Online and in person:

- Premed clubs at your university

- Nontraditional / late premed groups (many exist online)

Be cautious with online advice. Cross‑check anything that affects your timeline or finances against:

- Official med school websites

- AAMC guidance

- A trusted advisor

Step 10: Execute, Monitor, and Adjust

Once your plan is built, you are not done. You are starting a multi‑year project.

Quarterly review protocol:

Every 3 months:

Revisit your course performance:

- Any science grade below B? Intervene immediately (tutoring, lighter next semester).

Update your experience log:

- Track hours and reflections for clinical, shadowing, and volunteering.

- Note meaningful stories and lessons; these will feed your personal statement and interviews.

Check your timeline:

- Are you still on track for your planned MCAT date?

- Do you need to push application one cycle later to avoid rushing?

Mental health and bandwidth check:

- Are you burning out?

- Should you redistribute workload across an extra semester or summer?

Small, early corrections prevent big, painful failures later.

FAQ (Exactly 3 Questions)

1. Is it a problem if I take some or most of my prerequisites at a community college as a late pre‑med?

It depends on your context and target schools. If your 4‑year institution is available and affordable, most admissions committees prefer that the majority of your hard sciences be taken there, especially upper‑level biology and biochemistry. However, one or two community college courses (for example, a summer General Chemistry or Physics sequence) are usually acceptable, particularly if you:

- Perform very well (A/A– grades)

- Later succeed in more advanced science at a 4‑year school

- Earn a strong MCAT score that corroborates your mastery

Check specific schools’ policies; some state schools are more CC‑friendly, while a few highly selective schools are more conservative.

2. I am a senior with only a semester left. Should I delay graduation to fit in more prerequisites?

Delaying graduation can make sense if:

- You can afford the extra term(s) financially

- Your university’s science courses are stronger than local alternatives

- You want to keep access to campus resources (research, advising, pre‑health committee)

However, you do not need to force all prerequisites into your undergraduate degree. Many late pre‑meds graduate on time with their original major, then formally shift into a post‑bacc or non‑degree status for 1–2 years to complete sciences more deliberately. Compare costs, access to aid, and your mental bandwidth before committing to an extra year of undergrad tuition.

3. If I am switching late and will be older at matriculation, does that hurt my chances?

Being 1–5 years older than the traditional applicant generally does not hurt you. Many medical schools value applicants with additional maturity, life experience, and a tested commitment to medicine. What matters is not your age but whether your academic record, MCAT, and experiences clearly show you are prepared and genuinely suited for medical training. A well‑planned late switch with strong grades, a solid MCAT, and meaningful clinical/service work is far more competitive than a rushed traditional timeline with weak numbers and thin experiences.

Key takeaways:

- Late does not mean impossible; it means you must be deliberate, especially with prerequisites, MCAT timing, and GPA protection.

- Build a semester‑by‑semester plan that respects your constraints, then adjust it quarterly as real life happens.

- Use your “late start” as a strength by pairing a strong new science record with the depth and perspective from what you did before pre‑med.