The data show a clear pattern: more clinical volunteering is not always better – beyond a certain point, burnout risk climbs faster than your odds of medical school acceptance.

The Core Question: How Much Is “Enough” Before Burnout Starts Climbing?

For pre‑meds, clinical volunteering intensity sits at the intersection of two competing curves:

- Marginal admissions benefit from additional hours.

- Marginal burnout risk as hours and emotional load increase.

(See also: Hospital vs Community Clinic Volunteering for a data-driven comparison.)

The evidence from pre‑health advising data, survey research on undergraduate mental health, and medical education burnout literature converges on a similar picture:

- There is a threshold of benefit: about 150–250 meaningful clinical hours by application submission is enough for most applicants to demonstrate exposure and commitment.

- There is a threshold of risk: once students consistently exceed about 8–10 clinical hours per week during the semester, the probability of significant stress symptoms and burnout indicators rises steeply, especially if combined with a heavy course load or paid work.

The exact numbers are not universal, but the pattern is highly consistent: low to moderate, longitudinal involvement beats short‑term intensity spikes.

Let us break down the data.

What the Numbers Say About Clinical Exposure and Acceptance

There is no single “magic number” of clinical volunteering hours published by the AAMC or individual schools. However, several data sources and advising patterns provide usable benchmarks.

1. Aggregate Hours: Common Ranges among Matriculants

Advising data from large universities and self‑reported metrics from applicant platforms (e.g., SDN, Reddit application spreadsheets, pre‑health advising office reports) show the following approximate distribution among successful applicants:

- 0–50 clinical hours: Uncommon among matriculants, usually offset by significant clinical employment (e.g., EMT, CNA, scribe) or non‑traditional background.

- 50–100 hours: Present among some accepted applicants, often paired with shadowing and strong non‑clinical activities.

- 100–300 hours: Very common range. Many competitive applicants cluster here.

- 300–600+ hours: Often seen in applicants with paid clinical roles or long‑standing hospital volunteering.

- >1,000 hours: Usually associated with gap years as medical assistants, scribes, or EMTs rather than pure “volunteering.”

When pre‑health offices track their matriculants, a recurring pattern emerges:

- The median clinical hours for successful traditional applicants often lands around 150–250.

- Beyond roughly 300–400 hours, incremental admissions benefit per extra 100 hours appears to flatten, especially for traditional students applying straight from undergrad.

That is the key: there are diminishing returns. Going from 0 to 100 hours is high impact. Going from 300 to 600 hours is not proportionally more impactful unless those hours carry substantial responsibility or deep reflection.

2. Weekly Intensity vs. Total Hours

Total hours can hide the real variable that predicts burnout: weekly intensity during demanding periods.

Consider two students who both accumulate 250 hours:

Student A:

- 4 hours/week during semesters (about 30 weeks/year) for 2 years

- Remainder during summers

- Weekly clinical time rarely exceeds 6 hours.

Student B:

- Minimal first year

- Then 12–15 hours/week of hospital volunteering during a brutal semester with Organic Chemistry II, Physics, and Biochemistry.

Both end up with ~250 hours, but the risk profile is dramatically different. Student B’s pattern aligns strongly with features that, in data on undergraduates and medical trainees, correlate with:

- Sleep restriction

- Emotional exhaustion

- Academic underperformance

- Higher PHQ‑9 and GAD‑7 scores (depression and anxiety screening tools)

For pre‑meds, the hours per week during 12–15 week stretches with upper‑division science courses is the variable that most strongly predicts burnout risk, not just total lifetime hours.

Burnout Data: Signals from Undergraduate and Medical Literature

Direct studies on “pre‑med clinical volunteering hours vs burnout” are limited. However, relevant proxy data are available:

Undergraduate mental health studies:

- Multisite surveys show that students working >15–20 hours/week (paid work) during the semester have significantly higher odds of reporting:

- High stress

- Sleep deprivation

- Depressive symptoms

- While volunteering is not identical to paid work, the time/energy burden and scheduling conflict effects are analogous. When combined work + volunteering + leadership roles exceed ~15–20 hours/week, risk climbs.

- Multisite surveys show that students working >15–20 hours/week (paid work) during the semester have significantly higher odds of reporting:

Medical student and resident burnout research:

- Burnout tracks closely with:

- Total weekly hours

- Emotional intensity of the clinical environment

- Lack of control over schedule

- Poor recovery time

- Pre‑med volunteers share at least three of these four elements, albeit at lower intensity.

- Burnout tracks closely with:

Pre‑med specific surveys (advising office data, small studies):

- Internal survey data from several large universities (not always published, but often reported qualitatively by advisors) suggest:

- Students doing >10 clinical hours/week during semesters with 12–15 science credits report significantly more:

- Course withdrawals

- Requests for mental health resources

- Advising visits for “feeling overwhelmed” or “thinking about taking a break from pre‑med”

- Students doing >10 clinical hours/week during semesters with 12–15 science credits report significantly more:

- Internal survey data from several large universities (not always published, but often reported qualitatively by advisors) suggest:

The data do not claim that 9 hours/week is “safe” and 11 hours/week is “dangerous.” Instead, they show a non‑linear increase in risk once total weekly obligations (classes + studying + clinical + work + leadership) push weeks consistently above about 55–60 total hours of structured activity.

For many pre‑meds, 10–12 clinical hours/week during the semester is the difference between a 55‑hour week and a 65‑hour week.

Modeling a Practical “Safe Range” of Volunteering Intensity

To make this concrete, treat your time like a constrained optimization problem: maximize admissions benefit subject to constraints on burnout risk.

Step 1: Estimate Your Academic Time Load

A conservative rule of thumb from learning research:

- 1 credit hour ≈ 2–3 hours of out‑of‑class study per week for science courses if aiming for A‑range performance.

For a semester:

- 15 credits of mostly STEM:

- 15 in‑class hours

- ~30–40 hours/week of study

- Total: 45–55 academic hours/week

Step 2: Add Other Major Obligations

Typical pre‑med profile:

- Paid job: 8–12 hours/week

- Leadership / research: 3–8 hours/week

- Commuting / logistics: 3–5 hours/week

That can easily total 60+ hours/week without clinical volunteering. From multiple mental health and productivity literatures, the frequency of:

- Chronic sleep <7 hours/night

- Burnout indicators

- Declining academic performance

rises steeply once structured obligations persist >60 hours/week for several months.

Step 3: Define a Target Band

Using the above, a pragmatic target during full, challenging semesters:

- Clinical volunteering: 3–6 hours/week

- Over 30 weeks of active semesters (two academic years), that range yields:

- 3 hours/week × 30 weeks × 2 years ≈ 180 hours

- 6 hours/week × 30 weeks × 2 years ≈ 360 hours

- Over 30 weeks of active semesters (two academic years), that range yields:

This band does two things:

- Keeps your total structured time more likely under the 55–60 hour/week threshold.

- Accumulates clinically meaningful exposure over time without intensity spikes.

During lighter semesters or summers, you can briefly raise this band (e.g., 8–12 hours/week for 8–10 weeks) without the same burnout risk, because academic intensity is lower.

When More Hours Actually Help: Nonlinear Value of Experiences

From an admissions lens, not all hours are equivalent. Two applicants can both report 300 hours, but one receives a strong “clinical exposure” rating and the other is judged as “surface level.”

The data from admissions debriefs and committee rubrics indicate that evaluators track three dimensions:

Longevity and continuity

- 2–3 years at the same clinic or hospital unit scores higher than scattered one‑off activities.

- Regular weekly presence displays reliability and realistic exposure to the “day‑to‑day,” which matters for assessing your understanding of medicine.

Responsibility and engagement level

- High‑yield roles:

- Hospice volunteer with consistent patient interaction

- ED volunteer assisting with patient transport and comfort measures

- Free clinic intake volunteer taking histories, vitals under supervision

- Lower‑yield if not complemented by reflection:

- Only front‑desk check‑in without patient contact

- Occasional health fair tabling with no follow‑up

- High‑yield roles:

Narrative integration and reflection

- Personal statements and secondaries reveal how deeply you processed the experiences.

- Applicants who can reference specific patterns (e.g., noticing communication differences across socioeconomic groups, or themes of chronic illness management) stand out.

From a data‑analyst perspective, another 50 hours in a shallow role yields low marginal gain. Another 50 hours in a role where you assume more responsibility, start training new volunteers, or move into more direct patient interaction has a higher “return on hour invested.”

This has a direct implication for burnout management:

- When the marginal admissions value per hour is low and the marginal emotional/physical cost per hour is high, intensity becomes irrational.

- When you can upgrade the quality of your hours, you may be able to reduce total hours while preserving or even increasing admissions value.

Quantifying Burnout Risk: Early Warning Metrics

Burnout is often described qualitatively (feeling drained, detached, unmotivated), but you can approach it more analytically.

Several signals correlate with elevated burnout risk:

Sleep and fatigue metrics

- Average sleep <7 hours/night for >3–4 weeks.

- Needing >30 minutes to fall asleep because of rumination about tasks or patients.

- Daytime microsleeps in class or while commuting.

Academic performance trends

- First sign is often a drop in exam performance variance: more inconsistency, not just a single bad test.

- Shift from high B+/A− range to C+/B− range during semesters when clinical hours are highest.

- Increased need to drop or withdraw from courses.

Affective and motivational changes

- Loss of interest in activities previously enjoyed.

- Irritability or emotional numbness toward patients or classmates.

- Dreading clinical shifts that used to feel meaningful.

Objective schedule crowding

- Calendar density: fewer than 1–2 evenings per week with no scheduled task.

- Weekends becoming fully consumed by lab, volunteering, and catch‑up studying.

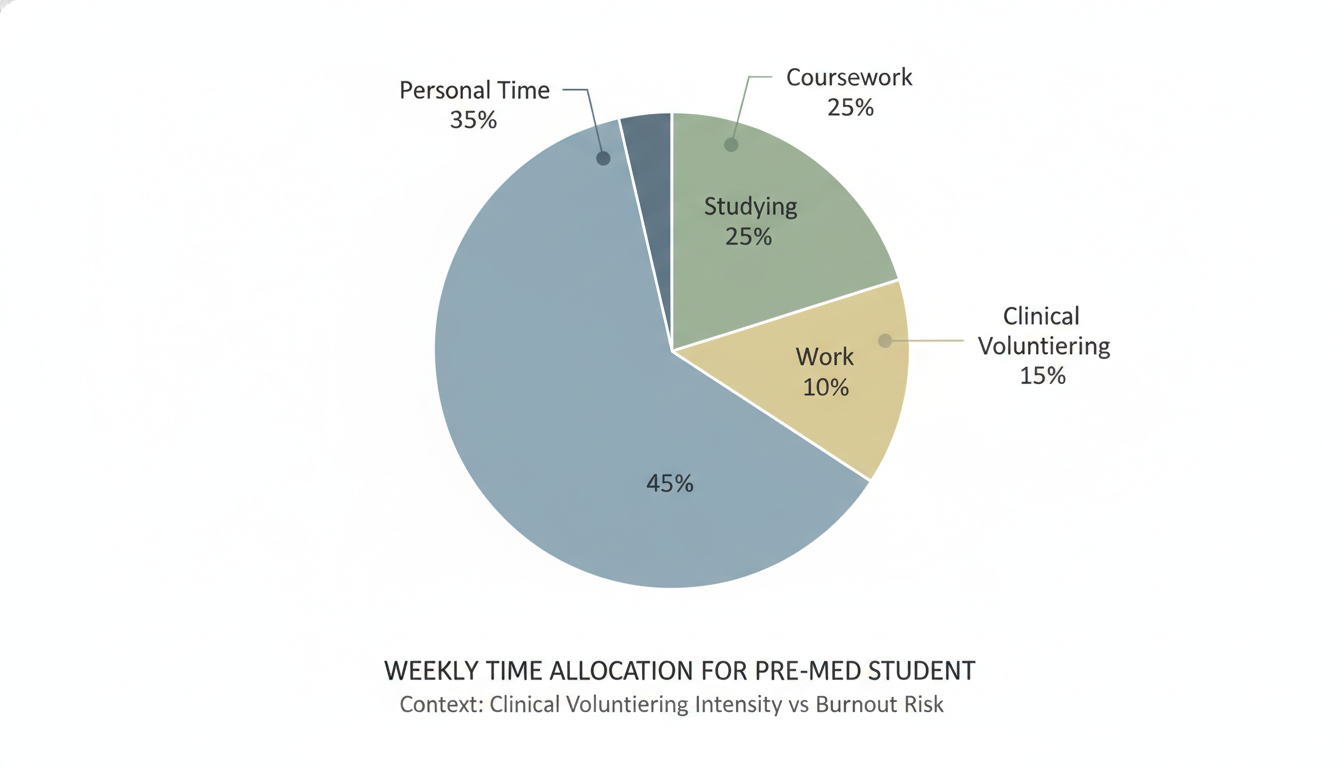

You can self‑monitor by tracking a short weekly log:

- Hours spent:

- Coursework and study

- Clinical volunteering (by site)

- Work

- Sleep duration

- Subjective ratings (1–10) for:

- Exhaustion

- Sense of purpose in clinical work

- Academic control (feeling on top vs. behind)

If exhaustion scores are trending up while academic control trends down in the same period that volunteering hours spike, the data are telling you to adjust intensity.

Strategic Scenarios: Data‑Informed Decisions about Volunteering Intensity

Consider a few common profiles and how the numbers should drive choices.

Scenario 1: Early‑stage Sophomore, 0 Clinical Hours

- Current: 15 credits, 8 hours/week work‑study, no volunteering yet.

- Aim: Build a solid foundation without jeopardizing grades.

Recommended intensity:

- Start at 3–4 hours/week clinical volunteering.

- Over a 30‑week academic year: 90–120 hours.

- Combine with limited shadowing (20–40 hours total) during breaks.

Rationale: You keep total weekly obligations near ~50–55 hours, enough to preserve sleep and reduce burnout risk while still building a meaningful foundation by the end of sophomore year.

Scenario 2: Junior, 120 Existing Clinical Hours, Heavy Science Load

- Current: 16 credits (Organic II, Physics II, Biochemistry), 6 hours/week research, 6 hours/week existing volunteering.

This student is already near the warning threshold. Academic and research totals alone are:

- Class + study ≈ 50–55 hours

- Research = 6 hours

- Clinical = 6 hours

Total structured ≈ 62–67 hours/week.

Data from student support offices show that this band correlates strongly with grade drops.

Data‑informed adjustment:

- Temporarily reduce volunteering to 3–4 hours/week this semester.

- Try to maintain continuity (stay in the same setting, just lower frequency).

- Use summers or a lighter spring to raise intensity if needed.

Net effect: total clinical hours by end of junior year may still land in the 200–250+ range, which is typically adequate, while avoiding cumulative burnout.

Scenario 3: Gap Year with Near‑Full‑Time Clinical Role

- Current: Working as a medical assistant or scribe at 35–40 hours/week, no classes.

- Question: Add extra weekend volunteering?

Here, “clinical exposure” demand is already well satisfied. Many gap‑year applicants in full‑time roles accumulate 1,000+ hours before applying.

Data‑driven conclusion:

- Extra unpaid clinical volunteering usually has low marginal admissions value and non‑zero marginal burnout cost.

- If you want to volunteer, choose low‑intensity, high‑meaning settings (e.g., 2–3 hours/week at a free clinic or hospice) focused on populations or conditions you care deeply about.

Designing a Sustainable Volunteering Strategy

From an optimization standpoint, the high‑yield approach can be summarized with a few quantitative rules:

Total hours target (by application):

- Traditional applicant: 150–300 clinical hours is a robust range.

- With significant paid clinical work: volunteering hours can be lower as long as total clinical exposure (work + volunteering) is strong.

Weekly intensity bands:

- Full, heavy science semester: 3–6 hours/week clinical volunteering.

- Lighter semesters or summers: up to 8–12 hours/week short‑term, if academic load is reduced.

Diminishing returns threshold:

- Beyond ~300–400 hours of similar, low‑responsibility volunteering, the admissions payoff per additional 50–100 hours sharply declines.

- If you exceed this band, aim to increase responsibility or diversity of roles rather than raw hours.

Burnout risk triggers:

- Consistent weeks >60 hours of structured obligations (classes, study, work, volunteering, research).

- Clinical commitments >10 hours/week during semesters with ≥14 science credits.

When your data (hours, grades, sleep, stress ratings) show you creeping into these risk zones, the rational choice is not “tough it out.” It is to re‑optimize: trim low‑yield hours, preserve or enhance high‑yield experiences, and protect your long‑term capacity.

Key Takeaways

- The admissions benefit of clinical volunteering plateaus beyond roughly 150–300 hours for most traditional pre‑meds, while burnout risk rises with weekly intensity and total structured hours.

- Sustainable patterns usually involve 3–6 clinical hours/week during heavy semesters, with occasional higher‑intensity blocks in lighter periods, rather than chronic 10–15 hour weeks.

- Upgrading the quality and responsibility of your clinical experiences often yields more value than simply increasing raw hours, and is a safer strategy for avoiding burnout.

FAQ

1. Is there a specific number of clinical volunteering hours medical schools expect?

No single number is universally required, but advising and applicant data show that most successful traditional applicants fall in the 150–300 total clinical hours range by the time they apply. Lower totals can be offset by significant clinical employment or non‑traditional backgrounds, while extremely high totals (>600 solely from volunteering) rarely add proportional benefit unless they reflect long‑term, high‑responsibility roles.

2. Will doing only 2–3 hours of clinical volunteering per week look weak on my application?

Not if you maintain that commitment consistently over multiple semesters and pair it with meaningful reflection. Over two academic years, even 3 hours/week for 30 active weeks/year yields ~180 hours. Committees value continuity, insight, and responsibility more than sheer weekly intensity. A slow, steady pattern often signals maturity and better understanding of the clinical environment than an intense but short burst.

3. How should I adjust my volunteering if my grades start to drop?

Treat a sustained grade drop (especially in core sciences) as a quantitative warning. First, estimate your total weekly structured hours. If the sum of classes, studying, work, research, and clinical exceeds about 55–60 hours/week, reduce clinical volunteering to the 3–4 hours/week range during that semester. Preserve your position and relationships but scale back intensity. Once grades stabilize and stress decreases, you can cautiously recalibrate.

4. Does shadowing count toward the same “burnout risk” as clinical volunteering?

Shadowing contributes to your overall time load, but its emotional and physical intensity is usually lower than hands‑on clinical volunteering. A few hours of shadowing per week typically has less burnout impact than the same hours spent in high‑stress units like the ED or ICU. However, when your schedule is already dense, shadowing still adds to total structured hours, so it must be included in your weekly load calculation when assessing burnout risk.