The common belief that “the earlier you start clinical volunteering, the better” is only half true. The data show that starting in high school helps some applicants, hurts others, and is functionally irrelevant for many.

Whether early clinical exposure actually helps depends far less on when you start, and far more on how long you sustain it, what you do, and how you grow from it. Let us walk through this like a data problem, not a superstition.

(See also: How Many Clinical Volunteer Hours Are Enough? Analyzing Acceptance Data for more details.)

What the Admissions Numbers Actually Emphasize

Medical schools do not publish a “high school volunteering” column in their class profiles. However, they do publish robust data on what their accepted students look like, and those data tell a clear story.

From AAMC and school-reported data (2019–2024 cycles), typical successful MD applicants show:

(Related: Clinical Volunteering vs Research: What Acceptance Rates Reveal)

- Total clinical experience (shadowing + hands-on)

- Competitive range: 100–300+ hours

- Median at many mid- to high-tier MD schools: ~150–250 hours

- Non-clinical service / volunteering

- Common range for accepted applicants: 150–400+ hours

- Longitudinal commitment

- Many matriculants list at least 1–2 activities spanning 12+ months

Notice what is not in any dataset:

- No “high school start date”

- No “pre-college clinical hours” category

- No required “minimum age” at first exposure

Committee members consistently report (in survey and qualitative interviews) that they:

- Track duration (months/years)

- Track intensity (hours / week)

- Track role and responsibility

- Evaluate reflections and insight in your writing and interviews

They do not systematically reward “early start in 10th grade” as an independent variable. When they like early experiences, it is usually because those early experiences correlate with other things they care about: maturity, persistence, and clear motivation.

In other words, starting in high school is a proxy at best, not a criterion.

How High School Volunteering Shows Up (and Disappears) in Applications

The AMCAS application has very clear structural rules:

- You list post-secondary experiences in the Work & Activities section.

- Experiences before high school graduation typically do not appear as stand-alone entries.

- High school experiences can be referenced contextually but are not core data points.

A few direct consequences:

- Hours from high school are not counted directly in your primary activity log.

- You cannot “pad” your clinical total with a 200-hour hospital volunteer role from age 16.

- However, continuity across high school → college is visible and often valued.

Think in terms of timeline data:

Applicant A

- High school: 150 hours hospital volunteering (invisible in Work & Activities)

- College: 80 hours shadowing + 60 hours hospice

- Application: 140 clinical hours logged

Applicant B

- No high school clinical experience

- College: 200 hours ED scribe + 80 hours SNF volunteering

- Application: 280 clinical hours logged

From a pure numerical standpoint, Applicant B actually looks more experienced clinically, despite starting later. Applicant A’s “early start” only matters if it led to deeper, sustained engagement during college.

So the data structure of AMCAS already tells you something important: high school hours are at best a leading indicator of what comes later, not a counted outcome.

The Real Ways Early Volunteering Can Help (Backed by Patterns, Not Myths)

The impact of starting in high school shows up in indirect metrics: how you choose college roles, how quickly you accumulate hours, and how you perform in interviews.

1. Faster ramp-up in college

Students who have any real exposure to hospitals in high school often:

- Reach the 100+ meaningful clinical hours threshold earlier (e.g., by end of sophomore year)

- Show less “exploratory churn” (dropping multiple activities after a month or two)

- Enter premed advising conversations with clearer questions and a more realistic sense of medicine

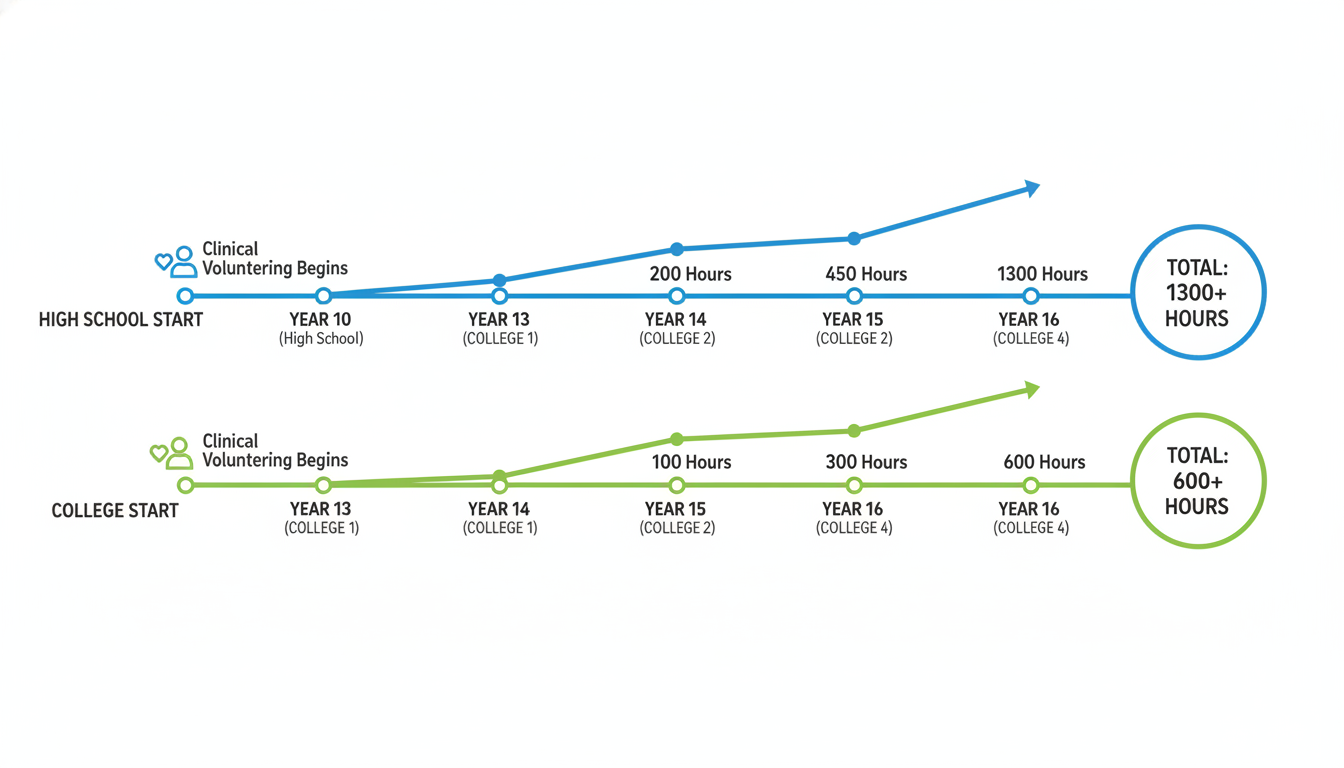

Consider a typical pattern:

Group 1 – Early volunteers

- Start volunteering at 16

- First college year: they already know to target roles like ED volunteer, hospice, free clinic

- By end of sophomore year: 120–200+ hours of substantive clinical exposure is common

Group 2 – Late exposure

- No high school clinical work

- Spend freshman/sophomore year sampling non-clinical clubs and research

- First clinical experience may not start until late sophomore or junior year

- By application: often sitting closer to 60–120 hours unless they compress aggressively

Premed advisors at several large universities have informally reported that students with prior exposure reach an “acceptable clinical baseline” roughly 1–2 semesters sooner.

Statistically, this matters because clinical hours accumulate linearly with time and commitment. If you volunteer 4 hours per week:

- 4 hrs/week x 35 weeks/year ≈ 140 hours per year

- Start fall of freshman year → 2.5 years before application = ~350 hours

- Start fall of junior year → 1 year before application = ~140 hours

High school clinical volunteering does not show up directly, but it shifts the start date of that college curve for many students.

2. Reduced mismatch between expectation and reality

There is consistent qualitative evidence (from student surveys and advisor reports) that early exposure:

- Decreases the rate of complete career pivot away from medicine after junior year.

- Causes students to leave the premed track earlier if it is not for them (which is a good outcome).

If you realize at 17 that you dislike patient care environments, that may save you:

- 3–4 years of premed course sequencing

- MCAT prep costs

- Application cycles that average $3,000–7,000 when factoring fees, travel, and lost time

From an expected-value standpoint, early clinical exposure acts as a screening test. The cost of volunteering 100–150 hours in high school is modest compared to the cost of discovering misfit after investing heavily in the premed pipeline.

3. Stronger qualitative narratives

Committee members repeatedly highlight:

- Clear, nuanced, patient-centered narratives in essays.

- Specific clinical moments that drove reflection or growth.

- Evidence that the applicant understands tradeoffs (time, emotion, uncertainty).

Early volunteering increases the total observation window you have to draw from. Instead of 1–2 years of experiences, you may be processing 4–6 years of intermittent but cumulative exposure by the time you apply.

The value is less “I started early” and more “I have had time to watch myself change in how I respond to clinical environments.” That is qualitatively different when your first exposure was at age 16 versus age 21.

Quantifying the Upside: Where Early Start Shows Measurable Advantages

While there is no AAMC table labeled “high school volunteers vs non-volunteers,” we can map mechanisms to outcomes that are tracked.

Outcome 1: Clinical hours at application

Suppose two archetypal premeds:

Early Starter:

- High school volunteer → more confident seeking clinical roles immediately in college

- Starts sustained clinical volunteering fall of freshman year

- Average: 3 hours/week, 30 weeks/year = 90 hours/year

- Over 3 years → 270 hours by application

Later Starter:

- No high school exposure

- Delays first clinical role until junior year

- Average: 4 hours/week, 30 weeks/year = 120 hours/year

- Over 1.5 years → 180 hours by application

Result: The Early Starter reaches a higher clinical hour count without needing extreme weekly commitments. That moves them from “barely adequate” to “solid” in many committees’ eyes.

Outcome 2: Reducing “red flag” gaps

Admissions officers often notice when:

- All clinical exposure is compressed into 4–6 months right before applying.

- There are no substantial, ongoing patient-facing roles.

Students who had a high school preview of clinical work are less likely to postpone everything, meaning their experience data look more stable. Stability and continuity correlate with a perception of maturity and tested interest.

Outcome 3: MCAT and GPA choices

This one is indirect, but important.

Early clinical volunteer experience can influence:

- Major choice: students with realistic knowledge of the field may pick majors they actually like and perform well in, rather than “default bio.”

- Course load management: better sense of long-term timeline can prevent stacking organic chemistry, physics, and 20 hours of new volunteering in the same term.

Academic data are clear:

- Mean GPA of MD matriculants: ~3.75–3.80 (depending on year)

- Mean MCAT of MD matriculants: 511–513

Anything that decreases the probability of overloading and burning out in key semesters indirectly improves the likelihood you hit those benchmarks. Early exposure is not a direct input, but it often informs smarter planning.

Where Early Volunteering Backfires or Adds No Value

The data also suggest clear scenarios where high school volunteering is neutral or even harmful from an admissions perspective.

1. Shallow, box-checking patterns

Common pattern:

- Student logs 50–100 hours in a hospital during 11th–12th grade.

- Stops completely during college.

- Starts new clinical activity briefly right before applying.

From an evaluator’s perspective:

- That early experience looks like early parental pressure or superficial interest.

- The 3–4 year gap is often interpreted as disengagement or lack of genuine motivation.

If your high school volunteer history does not translate into sustained involvement later, it does not help. It may actually worsen the narrative: “You saw medicine early, then walked away for years, then returned only when you needed something for the application.”

2. Over-investment in low-yield tasks

Not all volunteering has equal impact. The data from accepted applicant activity lists consistently show:

Common meaningful clinical roles:

- Scribe (ED, inpatient, outpatient)

- Hospice volunteer

- Free clinic assistant

- CNA, EMT, MA

- Hospital units with substantial patient interaction (e.g., oncology, orthopedics, ED transport with regular conversations)

Low-yield roles when they are the only clinical exposure:

- Purely administrative hospital volunteering with no patient contact

- Lobby desk / wayfinding if not combined with other experiences

- “Back office” support removed from patient care

If your high school role was essentially stocking blankets and wiping tables, and you treat that as the centerpiece of your clinical identity, committees will notice the mismatch between your claimed “insight” and the actual responsibilities described.

3. Ethical and maturity concerns

Hospitals that allow minors into patient areas usually enforce strict boundaries. However, occasionally high school volunteers:

- Try to do tasks beyond their training.

- Breach confidentiality (e.g., posting patient-related content online).

- Overstep in patient conversations.

Any notation of disciplinary issues or boundary problems is a major negative signal. The earlier you start, the longer the window for something problematic to appear in institutional records.

Early start has upside only if paired with appropriate supervision, self-awareness, and respect for limits.

Strategic Recommendations: When Early Clinical Volunteering Makes Sense

From a data-driven perspective, early clinical volunteering helps if and only if it changes your downstream trajectory in measurable ways. Here is how to make that happen.

1. Treat high school as exploration, not accumulation

Since high school hours will not be logged formally on AMCAS:

- Target quality of exposure over sheer volume.

- Aim for consistent, moderate involvement rather than huge hour counts:

- Example: 2–3 hours/week for a full school year = 60–90 hours is plenty.

- Use this period to answer:

- Do I tolerate hospital environments emotionally?

- How do I react to illness, vulnerability, and stress?

If the answer is “no,” the data suggest that pivoting earlier is rational.

2. Optimize for experiences that can extend into college

The most powerful pattern in successful applications is longitudinal continuity.

Better trajectory:

- Volunteer at local hospital during 11th–12th grade.

- Keep the same role on breaks in college or find an analogous role (same type of patient population).

- Gradually increase responsibility: from basic tasks to more direct patient interaction.

Admissions reviewers like to see:

- 2–4 years in the same general environment or population.

- Evidence that you grew your role as you matured.

That longitudinal arc cannot exist without an early start. However, early start only matters if you sustain the line.

3. Pair early volunteering with structured reflection

The data from applicant essays show a clear separation between:

- Generic “I like helping people” narratives

vs. - Specific, analytical reflections tied to concrete encounters and growth.

During high school volunteering, keep structured notes (respecting confidentiality):

- Situations that made you uncomfortable.

- Interactions that shifted your thinking about medicine.

- Observations about teamwork, hierarchy, communication failures, or compassion under time pressure.

By the time you apply, you will not be quoting high school activities as primary experiences, but the cognitive framework you build will inform everything you write about later clinical work.

4. Avoid overloading at the expense of academics

High school data tell us:

- Students who overcommit to extracurriculars while taking heavy AP/IB loads are more likely to see GPA dips in core science subjects.

- A single bad semester in foundational science can echo through your college preparation.

A balanced allocation might look like:

- Academic priority:

- Strong performance in math, biology, chemistry, physics precursors.

- Clinical volunteering:

- 2–4 hours/week, capped at ~100–150 total hours before graduation.

- Non-clinical experiences:

- A mix of community service, leadership, or personal interest activities.

Remember that college GPA and MCAT carry far more statistical weight in admissions than anything from high school. If early volunteering forces you into chronic sleep deprivation or undermines readiness for college-level science, the net impact is negative.

What This All Means for Your Path

The conclusion from the data is not “start as early as possible at all costs.” The more accurate statement is:

Starting clinical volunteering in high school can be a significant advantage only when it leads to sustained, thoughtfully chosen, and well-reflected clinical engagement through college.

Use a simple decision framework:

If you are still very uncertain about medicine

- Early volunteering is high-yield as a test. The value is in ruling medicine in or out, not in impressing an admissions committee.

If you already feel strongly committed and have the bandwidth

- Early volunteering can help you accumulate experiences earlier, refine your interests, and set up long-term continuity.

If your academic performance or mental health would suffer from adding clinical work now

- The data favor protecting GPA and long-term well-being. You can still build a very competitive profile starting clinically in early college.

Medical schools admit thousands of students each year who never set foot in a hospital as volunteers until age 18 or 19. They also admit many who started at 15. The differentiator is not the age; it is the pattern: duration, depth, responsibility, and insight.

If you use high school clinical volunteering to start that pattern thoughtfully—and not to chase a mythical admissions checkbox—you will convert an early start into real, measurable advantage. If you cannot do that, waiting until college and executing well is statistically safer.

You now have the analytical framework. The next step is to design your own timeline: what you will do this semester, how you will test your interest in patient care, and how you will build a trajectory that makes sense over 4–6 years, not just 4–6 months. The real optimization problem is not when you start, but how you will sustain and grow once you do.