The belief that “you must have funded research to stand out” is overstated, and the data show a much more nuanced picture.

For premeds and medical students, funded vs unfunded projects are not simply a prestige question. They map onto different roles, expectations, and outcomes in ways that admissions committees and residency program directors understand quite clearly. When you look at the numbers from AAMC, NRMP, and institutional outcomes, the pattern is consistent: grant support amplifies certain advantages, but strong, well-executed unfunded projects often contribute more to your trajectory than weakly engaged funded work.

Let us look at what the data actually say.

(See also: Premed Research and Acceptance Odds for more details.)

What “Funded” vs “Unfunded” Really Means in Practice

Before comparing outcomes, the categories themselves need clarity. The funded/unfunded divide is not binary in the way students often imagine.

Funded projects typically involve:

- External or internal money supporting the work

- A principal investigator (PI) who holds the award

- Budgeted items: personnel, assays, software, participant compensation, etc.

- Formal oversight (IRB, progress reports, sometimes data safety monitoring)

- Named mechanisms: NIH R-series, F-series, T32, foundation grants, internal pilot awards, summer research scholarships

By contrast, unfunded projects include:

- Chart reviews done with existing data and staff

- Quality improvement (QI) initiatives using routine clinical data

- Case reports and case series

- Retrospective observational studies with minimal incremental cost

- Small educational or survey projects run with existing department support

From the student perspective, “funded” often really means:

- A lab or group with existing infrastructure.

- A PI with a successful track record.

- Availability of paid time (summer stipend, hourly RA, or formal fellowship).

Those three variables—lab maturity, mentor track record, and protected time—are what drive outcomes more than the mere presence of a grant ID in the methods section.

What the Data Say about Research Volume and Outcomes

For Premedical Students

The AAMC’s data on successful applicants show a clear pattern: research experiences correlate with higher acceptance rates, but the “funded vs unfunded” label is not tracked directly.

From AAMC “Matriculating Student Questionnaire” and Application/Acceptance data (2021–2023 cycles):

- Among matriculants, roughly 60–65% report at least one research experience.

- Among non-matriculants, that proportion is closer to 50–55%.

- Applicants with ≥2 research experiences and ≥1 presentation or publication have acceptance rates roughly 8–12 percentage points higher than those with no scholarly output, controlling crudely for MCAT and GPA bands.

However, there is no data field on AMCAS that distinguishes whether those projects were funded. The outcome variable that matters is output: abstracts, presentations, posters, and peer-reviewed publications.

Small-scale institutional analyses support the same conclusion:

- At one large public medical school (data reported in advising presentations, 2018–2022), accepted applicants with ≥1 publication outnumbered those without publications by a factor of about 2:1, but internal review showed at least half of those publications came from projects that were unfunded or only lightly supported with departmental resources.

- At a high-research private school, the premed office reported that >70% of publications listed by applicants emerged from labs with funding, but only ~30–40% of the listed works directly acknowledged a major external grant. Many “funded” environments produced “unfunded” subprojects that still led to authorship.

The implication is straightforward: admissions readers see evidence of meaningful scholarly engagement—not a ledger of grant dollars.

For Medical Students and Residency Applications

The NRMP Charting Outcomes in the Match reports give more granular data. Again, they track:

- Number of “abstracts, presentations, and publications” per applicant

- USMLE Step scores

- AOA, clerkship grades, etc.

They do not track whether those scholarly items were produced under funded vs unfunded projects.

Patterns from Charting Outcomes 2022 (U.S. MD seniors):

Mean number of research items for matched vs unmatched applicants:

- Dermatology: matched 18.3 vs unmatched 15.8

- Radiation Oncology: matched 21.7 vs unmatched 14.1

- Orthopedic Surgery: matched 14.4 vs unmatched 8.5

- Internal Medicine: matched 6.6 vs unmatched 5.0

Across competitive specialties, the difference is larger in count of scholarly output, not documented funding source.

Internal residency selection data from several programs (shared in conferences and advising sessions) report typical distributions:

- In competitive specialties, a substantial proportion of top applicants report at least one project tied to an NIH or major foundation grant.

- But committees often treat a first-author paper from a small, unfunded retrospective study similarly to a middle-author paper produced under a massive R01.

The visible metrics remain:

- First vs middle authorship

- Prospective vs retrospective

- Clinical relevance

- Publication venue and impact factor

- Evidence that the applicant understood design, analysis, and limitations

“Funded vs unfunded” is largely a proxy for environment, not a direct scoring item.

Where Funding Makes a Measurable Difference

The data show several consistent advantages tied to funded environments, even if grant dollars are not explicitly credited on your CV.

1. Publication Probability and Time to Output

Funded labs tend to have higher throughput.

Several institutional audits of student research output show:

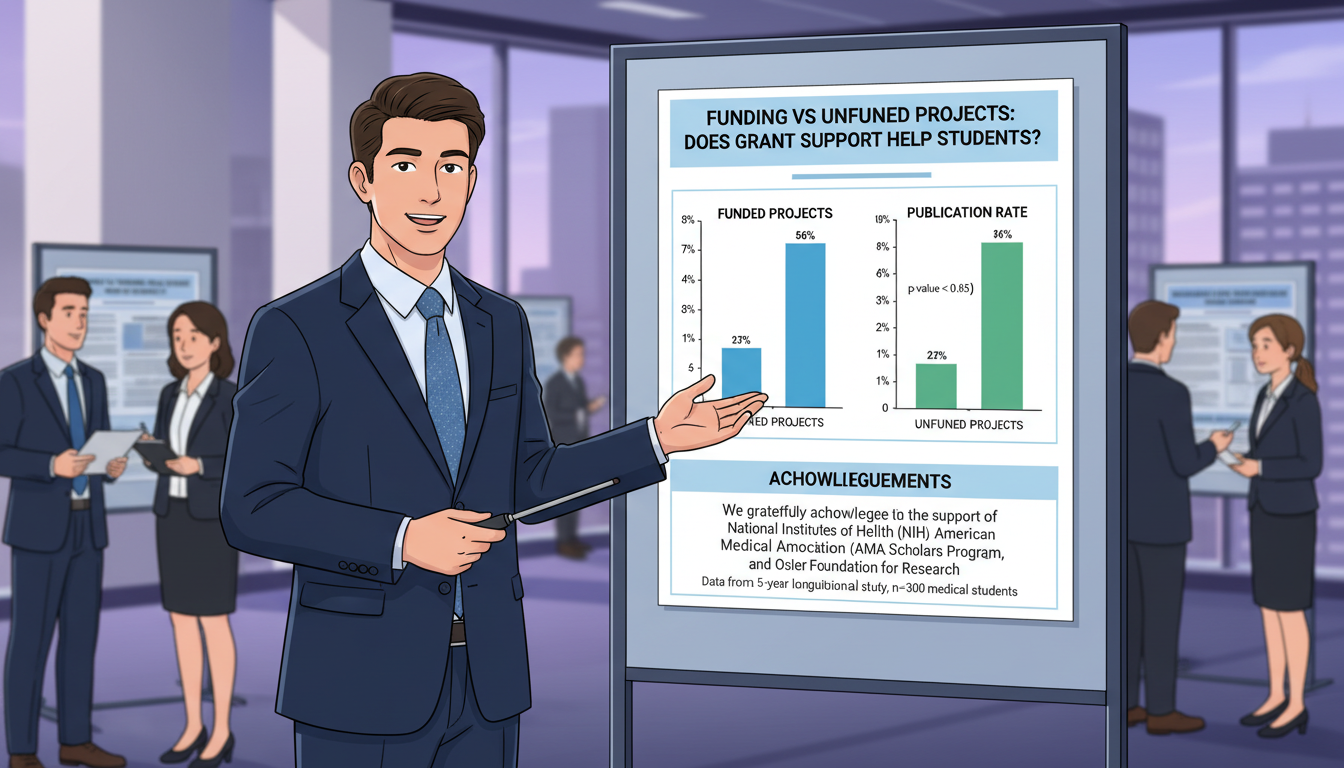

Students in established, externally funded labs have higher publication rates. For one midwestern medical school (2016–2020 data, n≈400 students):

- Students working in labs with at least one active NIH R01 in the department:

- ~65% eventually listed ≥1 peer-reviewed paper from that work.

- Students working in environments with no external grant support:

- ~35–40% reached a publication, though many had abstracts or posters.

- Students working in labs with at least one active NIH R01 in the department:

Time to first publication:

- Funded, high-throughput labs: median ~18–24 months from project start.

- Unfunded, PI-initiated small projects: median ~30–36 months.

Cycle times matter. When you start a project as a sophomore premed or M1 with only 12–18 months of available time before applying, every month of delay decreases the chance that the paper appears on your ERAS or AMCAS application.

Funding often correlates with:

- Dedicated coordinators who handle IRB submissions quickly.

- Established data pipelines (EHR extracts, REDCap databases).

- Existing analysis code or statisticians, reducing analytic bottlenecks.

These factors make the probability that your work leads to a citable product significantly higher—even if your specific task is on a tiny, “unfunded” subset of the PI’s broader funded program.

2. Access to Protected Time and Paid Roles

The largest direct benefit for students is not the presence of a grant number. It is money that pays for protected time.

Examples:

- NIH or institutional summer research programs often provide $3,000–$6,000 stipends.

- Year-long research fellowships or HHMI-type programs may support a student with $25,000–$35,000 for a “research year”.

Comparative observations from multiple institutions:

- Students with a paid research year (typically in funded environments) often end up with 3–6 publications, multiple conference abstracts, and sometimes first-author work.

- Students in unpaid, part-time projects during a standard curriculum year more commonly produce 0–2 publications, often as middle authors.

The input variable that matters most here is hours invested. A funded fellowship might allow 1,500–2,000 hours of focused research in a year. A typical student doing “side” research during M2–M3 may manage 150–300 hours total.

The data are predictable: more hours plus better infrastructure yields more output.

3. Network Effects: Letters and Reputation

Funded PIs typically:

- Publish more, so they are better known to admissions or residency committee members.

- Hold roles on study sections, editorial boards, or selection committees.

- Supervise more trainees, which gives them comparative context for letters.

In outcome terms:

- A strong letter from a well-known, well-funded PI tends to carry more weight in borderline cases than a letter from a less-published, local clinician with no research footprint.

- Students from T32- or big-center environments often report that a single phone call or email from their PI to a program director yielded extra interview consideration.

There is no formal “grant bonus” on an evaluation rubric. Instead, the grant environment enhances the credibility and visibility of whatever you produce.

Where Unfunded Projects Perform Surprisingly Well

If funded projects had an overwhelming causal advantage, you would expect students without access to grants to be routinely excluded from competitive specialties. That is not what the data show.

1. Case Reports, QI, and Retrospective Studies as Efficient Output

Look at successful applicants’ CVs:

- In many specialties, particularly during medical school, a sizable fraction of “abstracts, presentations, and publications” are case reports, QI projects, or brief retrospective analyses. These are frequently unfunded.

- Internal analyses at several schools show that 20–40% of student publications acknowledge no direct grant support.

These projects can be:

- Faster from initiation to submission (often <12 months).

- More amenable to first authorship for students.

- Easier to scope to a realistic student-owned piece.

For example:

- A single interesting case in neurology can become:

- A case report (journal article).

- A poster at a specialty meeting.

- A brief invited review if the topic is rare.

All of that is typically unfunded yet yields three “scholarly items” on ERAS or AMCAS.

2. Evidence of Ownership and Analytical Skill

Coarse output counts obscure the qualitative signal that evaluators look for: what did the student actually do?

Students on smaller, unfunded projects often:

- Design the data collection themselves.

- Perform their own statistical analysis (e.g., basic logistic regression, survival analysis).

- Write the bulk of the manuscript.

Compare two applicants:

- Applicant A: Middle author on four R01-based projects; did data entry, attended meetings, wrote no sections.

- Applicant B: First author on a single, unfunded retrospective study; handled design, data extraction, analysis, and writing under mentorship.

On paper, A has more items. In an interview, B can usually defend methods, discuss limitations, and articulate next steps far more convincingly. Many experienced interviewers value that depth of understanding more than an inflated publication count.

Multiple program directors across internal medicine, pediatrics, and surgery have made this explicit in surveys and panel discussions: they care about evidence of critical thinking and ownership, not just the presence of an NIH grant number in your experience description.

3. Access for Students at Schools with Lower Research Intensity

The AAMC classifies medical schools as “high”, “medium”, or “low” research intensity. Students at lower-intensity schools often have few options for large funded projects.

Yet NRMP outcomes show that:

- U.S. MD seniors from mid-tier and low-research schools still match into competitive specialties each year.

- Their CVs frequently emphasize unfunded clinical projects, regional presentations, and strong clinical performance, rather than major external grants.

Admissions and residency selection committees are aware that not every institution has the same research ecosystem. They typically evaluate candidates in the context of opportunity, not in absolute dollar terms.

Does Grant Support Help Students? A Data-Based Answer

The most reasonable reading of the available evidence is:

Grant support helps indirectly and unevenly. It is beneficial at the population level but not determinative at the individual level.

We can translate this into four practical conclusions.

1. Funding Improves Infrastructure, Which Increases Output

On average:

- Students in funded labs produce more publications and presentations.

- They achieve output faster.

- They gain access to support staff, statistical expertise, and established protocols.

These advantages are quantifiable: in many institutional samples, a 20–30 percentage point increase in publication likelihood.

For premeds and medical students trying to maximize the probability of having citable work before applications, this is non-trivial.

2. Funding Is a Strong Signal When It Is Yours

There is one case where funding clearly and directly helps: when the student is the named recipient.

Examples:

- Undergraduate research grants

- Medical school summer research scholarships

- NIH F30/F31, MSTP T32-related awards, or foundation fellowships

- Society-funded medical student research grants (e.g., AHA, ASCO, etc.)

Being PI or co-PI on a student-level grant signals:

- Initiative in designing a project.

- Ability to write a structured proposal.

- External validation by a review panel.

Data from several schools show that only a small fraction of students pursue or receive such awards, often <10–15% of each class. Those who do tend to cluster among the top applicants to research-focused residency programs and MD/PhD paths.

3. But Most Evaluation Rubrics Do Not Explicitly Score Grant Dollars

Across:

- Medical school admissions rubrics

- Residency application filters

- Dean’s letter templates

The common quantitative metrics are:

- Number of abstracts/presentations/publications

- First-author vs middle-author

- Types of projects (basic, translational, clinical, QI, educational)

- Honors in research electives or thesis requirements

Grant participation is often mentioned in narratives but not coded as a numeric score. There is no “+2 points for NIH R01 involvement” field.

In other words, funding tends to shape the environment that generates the metrics that do appear on score sheets. It usually does not appear as a metric itself.

4. Unfunded Does Not Mean Unimportant

From a data analyst perspective, equating “unfunded” with “low-value” is simply inaccurate.

Some domains are classically low-cost and low-funding:

- Medical education research

- Many QI initiatives

- Secondary analyses of existing clinical trial data

- Literature reviews and meta-analyses done with existing software access

Yet all of these are heavily represented in student publications and conference posters. They are overrepresented in first-author works by students because they are more feasible to own end-to-end.

Committees can clearly distinguish:

- A thoughtful, methodologically sound, unfunded project where the student can discuss effect sizes, confidence intervals, and limitations.

- A shallow, box-checking activity in a big-data lab, regardless of how many grants the PI holds.

Strategy: How to Use This Data to Make Decisions

Given this landscape, how should a premed or medical student allocate finite time?

Prioritize Mentor Quality Over Funding Status

If you have a choice between:

- A well-funded but diffuse lab where you are one of many nameless undergrads or MS1s, and your role is pure data entry.

- A smaller, unfunded project with a mentor who meets regularly, teaches you analysis, and wants you on as first author.

The data suggest the second route is often more advantageous for:

- Skill acquisition

- Authorship quality

- Interview talking points

Look for:

- Clear expectations about your role.

- A track record of students getting publications from that mentor.

- Evidence of timely feedback and accessibility.

Use Funded Environments Strategically

If you can enter a funded environment with:

- A defined subproject.

- Reasonable probability of authorship.

- Access to statisticians, coordinators, and structured timelines.

Then you capture both sets of advantages:

- Volume and speed from the infrastructure.

- Ownership and skill from a discrete piece of analysis or writing.

Students who maximize outcomes often follow this pattern:

- Start in a funded lab for exposure and network.

- Peel off a smaller, partly independent project (often retrospective or QI) that they can drive to completion, even if that piece itself has no separate grant.

Time Horizon Matters More Than Funding Label

Align project choice with your application timeline:

For premeds starting research in junior year with a plan to apply in one year, lengthy, grant-heavy basic science projects are unlikely to yield a completed paper in time. Focus on:

- Retrospective clinical studies

- Case reports

- Education or survey projects

For M1s or M2s with longer runway or those planning a research year, funded lab projects can pay off more:

- Prospective trials

- Mechanistic bench work

- Longitudinal cohort analyses

Ask every potential mentor a data-focused question:

“What proportion of your students over the last 5 years have gotten a publication from working with you, and on what timeline?”

Their answer is a far better predictor of your outcome than a simple “yes/no” about funding.

Key Takeaways

- Grant support helps students indirectly by improving infrastructure, speed, and mentorship networks, but it is not scored directly in most admissions or residency rubrics.

- Strong, well-mentored unfunded projects can match or exceed the career impact of loosely engaged work in funded labs, especially when they yield first-author output and real analytical understanding.

- The optimal strategy is to prioritize mentor quality, project ownership, and realistic timelines over chasing the “funded” label; the data show that these factors predict meaningful research outcomes far more reliably than the presence of a grant number.