Only 38% of applicants with ≥5 total research “experiences” have a peer‑reviewed publication by the time they apply, yet over 80% report at least one presentation or abstract. That imbalance shapes how program directors interpret “scholarly activity” and what actually predicts match success.

The data show a clear pattern: publications and presentations do not carry equal weight, and their impact varies dramatically by specialty and by how competitive an applicant already is. Treating them as interchangeable “research boxes” to tick is a strategic error.

Let us quantify that.

(See also: Time Investment vs Output for more details.)

What the Match Data Actually Measure

Most of what applicants believe about research comes from anecdotes. Program directors, however, respond to numbers.

The primary data streams here are:

- NRMP Program Director Survey (2018, 2020, 2022)

- NRMP Charting Outcomes in the Match (US MD, DO, and IMG editions)

- AAMC and AACOM applicant-level research metrics

- Specialty-specific surveys and retrospective cohort studies

Across these datasets, “research productivity” is captured in two broad ways:

Count of research experiences

- Any project labeled “research” on ERAS

- Includes basic science, clinical projects, quality improvement, public health, and sometimes even literature reviews

Count of “publications, presentations, and posters” (PPP)

- A single composite number on ERAS and in NRMP tables

- Lumps together:

- Peer‑reviewed publications

- Non–peer reviewed pieces (e.g., blogs, newsletters)

- Oral presentations (local, regional, national, international)

- Poster presentations (same scale)

- Abstracts and published meeting proceedings

This is the first problem: most official statistics do not separate publications from presentations.

So we have to read the data sideways:

- By looking at specialties where publications are almost required (e.g., Dermatology, Plastic Surgery)

- By comparing mean PPP counts of matched vs unmatched

- By examining program director ranking factors, where they explicitly rate “demonstrated involvement and interest in research” vs “number of publications”

The aggregate story: presentations are common, publications are a differentiator.

Publications vs Presentations: What the Aggregate Data Say

To compare publications and presentations as predictors of match success, it helps to define four broad applicant groups, based on national data patterns:

- No output (0 PPP)

- Presentations only (PPP > 0, but no peer-reviewed publication)

- 1–2 publications (often plus several presentations)

- 3+ publications (usually research-heavy trajectory)

Because NRMP aggregates PPP, we rely on:

- Specialty studies that separate pubs vs presentations

- PD surveys asking specifically about “peer‑reviewed publications”

- Indirect inference from means in research-heavy vs light specialties

Group 1: No Output (0 PPP)

NRMP’s 2022 Charting Outcomes show that across all specialties:

- US MD seniors with 0 PPP:

- Match rate in highly competitive specialties: often <40%

- Match rate in moderately competitive fields (IM, Peds, FM): usually >80% if Step scores are solid and clinical performance is good

For example (approximate national patterns, rounded):

- Internal Medicine (categorical), US MD:

- Matched with 0 PPP: ~80–85%

- Matched with ≥5 PPP: >95%

This suggests having any scholarly activity at all matters more than the specific type for mid-competitive fields.

However, for specialties like Dermatology, Neurosurgery, Ortho, ENT:

- Applicants with 0 PPP are both rare and rarely successful

- In some cycles, >90% of matched applicants in these fields report at least one research product

Conclusion from Group 1:

For low- and mid-competitive specialties, publications vs presentations matters less than simply not being at zero. For highly competitive specialties, 0 output is almost a disqualifier.

Group 2: Presentations Only

Here the data get more nuanced.

Most medical schools encourage (or require) at least one poster at a local or regional meeting. As a result, by graduation:

- 70–85% of US MD seniors report at least one poster or oral presentation

- Only 30–40% report at least one peer‑reviewed paper

Implication: presentations are the norm, publications are the exception.

When everyone has something, its marginal value in prediction declines.

Several specialty-specific analyses have tried to separate publication vs presentation effects:

A plastic surgery applicant study (multi-institutional, pre-2020) found:

- Total research items (abstracts, presentations, publications) correlated with matching

- However, in multivariable models, first-author publications remained significant, while number of presentations did not when controlling for pubs and Step scores

An orthopedic surgery analysis reported:

- Unmatched applicants had a mean of ~8–9 PPP vs 12–14 PPP for matched

- But when parsing a subsample with verified CVs, publications, not posters, distinguished the strongest applicants

The pattern repeats: presentations help show engagement, but once the bar of “some activity” is cleared, their predictive value plateaus quickly unless paired with publications.

From a data analyst’s lens:

Presentations are a binary screening variable (“do you do anything scholarly?”). Publications behave more like a continuous predictor (“how deeply? at what level?”).

Group 3: 1–2 Publications

This is the inflection zone.

Cross-specialty observations show that applicants with at least one peer-reviewed publication tend to:

- Have more research experiences overall

- Accumulate more total PPP

- Often work with more research-active mentors (who also write letters)

The confounders are significant. However, several signals stand out:

NRMP Program Director Surveys (e.g., 2022) often show:

- “Demonstrated involvement and interest in research” rated as moderately important, especially in university programs

- PDs in highly academic programs informally report: “one or two real publications” separate applicants more than “six posters”

A dermatology analysis (pre-Step 1 pass/fail, but still informative) showed:

- Matched applicants had a median of ~5–6 total publications vs ~1–2 for unmatched

- When controlling for USMLE scores and medical school prestige, having at least one first- or co-author original research paper significantly improved match odds

In practice:

- Moving from 0 to 1 publication tends to have more signal than moving from 1 to 5 presentations.

- That single publication often coincides with stronger mentorship and a more coherent narrative in the personal statement and interviews.

Group 4: 3+ Publications

At this level, we are often seeing:

- Dedicated research time (e.g., a gap year, scholarly concentration)

- Mentors with established labs or trial portfolios

- More substantive contributions to a specialty

Several competitive fields show a “dose-response-like” pattern:

- Orthopedic Surgery, Plastic Surgery, Neurosurgery:

- Mean PPP for matched applicants often >15–20

- A sizable fraction of this is publications and published abstracts

- Internal Medicine–Research Pathway and Physician-Scientist Tracks:

- PDs explicitly prioritize applicants with multiple first-author papers, often in PubMed-indexed journals

The data here align with PD behavior:

- When screening hundreds of applications, PDs cannot read every line of experiences.

- They frequently scan:

- “Number of peer‑reviewed publications”

- Journals recognizable in the field

- Presence of first-author work

Publications at this volume substantially change an applicant’s positioning, especially if paired with high board scores and strong clinical grades.

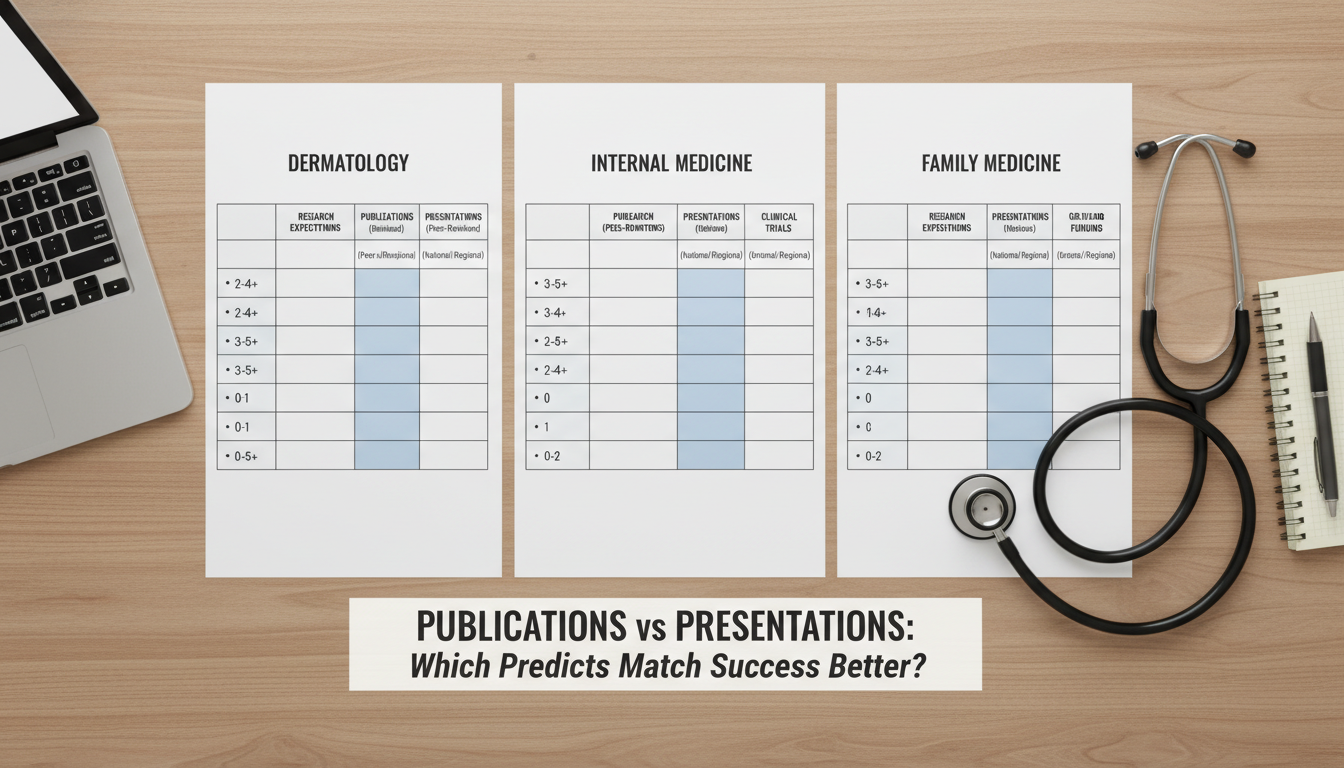

Specialty-Level Differences: When Output Type Really Matters

Looking across specialties, the weight of publications vs presentations is not uniform.

1. Research-Intensive, Highly Competitive Specialties

Examples: Dermatology, Plastic Surgery, Neurosurgery, Orthopedic Surgery, ENT, Radiation Oncology

Data signals:

- Mean PPP for matched US MD seniors often:

- 15–25+ items, sometimes more

- High proportion of those are:

- PubMed-indexed manuscripts

- Meeting abstracts in major specialty societies (which often publish proceedings)

Key points:

- Publications function almost like a threshold requirement; presentations alone rarely suffice in the top tier programs.

- Multi-center retrospective studies often find:

- Each additional publication slightly increases odds of matching, even after controlling for Step scores.

Here, publications predict match success better than presentations, particularly when:

- First-author

- In specialty-relevant journals

- Derived from robust projects (clinical trials, meta-analyses, significant retrospective cohorts)

2. Mid-Competitive, Academic vs Community Split

Examples: Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, General Surgery, Emergency Medicine

Researchers often divide programs into:

- University/academic programs

- Community programs

Academic internal medicine and pediatrics PDs consistently rate:

- “Demonstrated research interest” as more important than community programs

- Peer‑reviewed publications as a plus, especially for applicants expressing interest in fellowships (e.g., cardiology, heme/onc, GI)

In these specialties:

- Any scholarly activity (presentations or publications) improves application strength for most programs.

- Publications gain incremental value for:

- Applicants targeting university programs

- Applicants articulating future academic careers

From limited data, one publication likely offers more predictive value than multiple small, local posters. However, the relative importance is lower than in derm/plastics/neurosurg.

3. Less Research-Intensive Specialties

Examples: Family Medicine, Psychiatry, Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Pathology (for many community programs)

Charting Outcomes suggests:

- Many successful applicants in these fields have 0–2 PPP.

- Match rates remain high even with no publications.

Here:

- Presentations, especially quality improvement or community projects, often suffice to demonstrate initiative.

- A publication can help at top academic programs, but its predictive value for matching in any program is less pronounced.

For these specialties, time invested in clinical performance and strong letters often has a greater marginal impact than squeezing out another abstract.

Program Director Behavior: How They Interpret Output Types

Program Director Surveys shed light on how numbers translate into decisions.

Common findings (paraphrased across several survey cycles):

- PDs are wary of:

- Inflated research counts

- Minimal contributions listed as “co-author” on numerous posters

- They value:

- Evidence of sustained involvement

- Coherence between research, specialty choice, and narrative

When asked indirectly (via interviews, commentaries, and some survey free-text responses), PDs often distinguish:

- Presentations alone:

- Signal basic engagement

- Sometimes viewed as low-bar if local and one-off

- Publications:

- Suggest project completion

- Indicate ability to see work through multiple steps: data, writing, peer review

- Easier to verify quickly (PubMed search)

In prediction terms:

- Presentations are noisy, plentiful data points.

- Publications are sparser, higher-quality data points with stronger signal.

From a modeling perspective, if we were to build a logistic regression for “matched vs not matched”:

- Using both presentations and publications as predictors, controlling for boards and grades, the coefficient for publications would likely be larger and more stable, especially in research-heavy specialties.

- Presentations would matter most at the low end (vs 0), then their marginal contribution would flatten.

Strategy by Stage: Premed vs Medical Student

Since this article is pegged to “premed and medical school preparation,” the question is not only which predicts the match better, but when each type of output should be prioritized.

For Premeds

Medical schools evaluate:

- Depth and continuity of research engagement

- Understanding of scientific process

- Potential for future scholarly productivity

Most premeds will not have peer‑reviewed publications. Admissions committees know this.

Data from AAMC indicate:

- A minority of matriculants report formal publications

- Many report research experiences and, increasingly, posters at undergraduate conferences

For premeds:

- Participation matters more than product type.

- A well-documented research experience with:

- Clear role

- Strong letter from a PI

- Ability to talk through the hypothesis and methods carries more weight than chasing a low-quality poster for its own sake.

However, if you already have the option:

- A serious, first- or co-author publication in a biomedical field (not predatory) is a strong positive predictor of success in MD admissions, particularly at research-intensive schools.

Presentations help, but the incremental predictive value of a single undergraduate poster vs a strong research letter and narrative is limited.

For Medical Students (Planning Ahead)

Here the match data become directly relevant.

General strategy derived from the numbers:

Early MS1–MS2: Build foundation and mentorship

- Prioritize joining a project with:

- Proven track record of publishing

- A PI who mentors students regularly

- At this stage, the type of output is less pressing than the trajectory toward some products.

- Prioritize joining a project with:

MS2–MS3: Optimize for at least one publication

- Aim to convert at least one project into:

- A PubMed-indexed case report, brief report, or original article

- If the project is slow, augment with:

- Smaller, more straightforward papers (e.g., case series, retrospective chart reviews)

The data show that having at least one publication:

- Differentiates you from the median applicant in most fields

- Strongly differentiates you in competitive specialties

- Aim to convert at least one project into:

Presentations as byproducts, not primary targets

- Submit posters and abstracts along the way:

- National or regional meetings if possible

- Local research days are good but carry less weight

- Think of presentations as multiplicative:

- One paper can generate multiple posters over time

- Do not reverse the logic and pile up posters with no completed manuscripts if your goal is a research-heavy specialty.

- Submit posters and abstracts along the way:

MS3–MS4: Map to specialty norms

- If aiming for:

- Dermatology / Plastics / Ortho / Neurosurgery / ENT:

- Target multiple publications by ERAS submission, ideally 3+

- Emphasis on specialty-related work

- Internal Medicine / Pediatrics / General Surgery:

- At least one publication recommended for academic programs, especially if planning competitive fellowship

- Family Medicine / Psychiatry / PM&R:

- High PPP not mandatory; a publication is a positive, but balanced with clinical performance

- Dermatology / Plastics / Ortho / Neurosurgery / ENT:

- If aiming for:

In all cases, ensure the numbers line up with a coherent narrative: your research should make sense relative to your stated interests.

So Which Predicts Match Success Better?

Stripped of anecdotes and based on the available data:

At the low end (0 vs any output)

- Presentations and publications both predict better match outcomes compared with no scholarly activity.

- A single presentation can move you out of the “no research” category, which is helpful.

In the middle (some activity vs more activity)

- Publications carry more predictive weight than additional presentations.

- Moving from 0 publications to 1 matters more than moving from 1 to 5 presentations, especially in academic and competitive specialties.

At the high end (research-intensive trajectories)

- In competitive specialties and academic pathways, the number and quality of publications correlate more strongly with matching than sheer volume of posters and presentations.

- Program directors explicitly look for peer‑reviewed work and often give it more credence than multiple local presentations.

From a data analyst’s perspective:

If we treated each as a feature in a predictive model, publications have a higher signal-to-noise ratio than presentations, particularly when distinguishing strong from very strong applicants.

Key Takeaways

- Peer‑reviewed publications, especially first-author and specialty-relevant work, are more powerful predictors of match success than presentations, once you control for having “any” research at all.

- Presentations are valuable as a floor (avoiding 0 PPP) and as byproducts of real projects, but they show diminishing predictive returns compared with even a small number of solid publications.

- The optimal strategy is sequential: secure mentorship and experiences early, convert at least one project into a publication, and then leverage presentations to amplify that work rather than substitute for it.