Medical student planning [journal targeting strategy](https://residencyadvisor.com/resources/medical-research/retrospective-c](https://cdn.residencyadvisor.com/images/articles_v3/v3_RESEARCH_IN_MEDICINE_journal_targeting_strategy_matching_student_projec-step1-medical-student-planning-journal-targeti-5987.png)

(See also: Responding to Reviewer Comments for tips on handling feedback.)

You are three weeks away from finishing your first real research project. The figures look clean, your mentor is finally satisfied with the discussion section, and the lab has started asking the inevitable question: “So… where are we sending this?”

You open a browser to “look at journals” and immediately drown in options: specialty journals, society journals, “open access” journals, impact factors, indexing, APCs, submission portals. Someone suggests JAMA. Someone else laughs and says “start lower.” None of this feels systematic.

Let me break this down specifically.

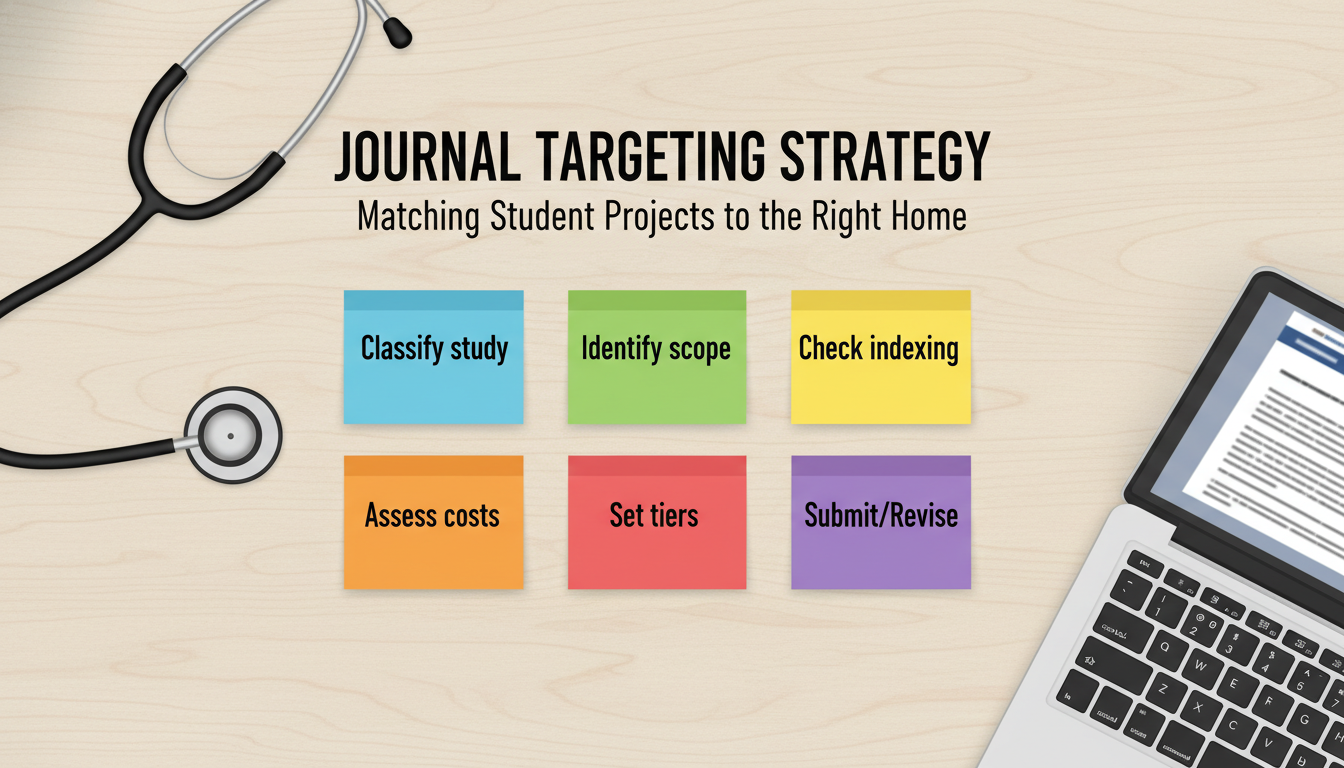

This is not about “shoot high and see what sticks.” A good journal targeting strategy, especially for students, is about aligning:

- The type and strength of your project

- With the scope and rigor of the journal

- While optimizing for your career stage and timelines

We will build a stepwise framework you can use for every project from first-year poster to senior-year first-author manuscript.

1. Start With Brutal Clarity: What Exactly Is Your Project?

Before touching a journal website, classify your project with the precision you would use in a methods section. Most students skip this step and jump straight to impact factors. That is backwards.

Ask four concrete questions.

1.1 What is the design and level of your study?

Classify rigorously, not aspirationally.

Common student project types:

Descriptive / Exploratory

- Single-center chart review with small sample sizes

- Surveys of classmates or single institution

- Quality improvement (QI) without strong statistical design

- Case reports / small case series

Analytical but Limited Generalizability

- Retrospective cohort from one institution

- Cross-sectional analysis of institutional data

- Educational intervention study in one course or clerkship

- Modest sample sizes, limited adjustment for confounders

Higher-Rigor Clinical / Translational

- Multi-center databases

- Robust regression modeling, survival analysis, propensity scoring

- Preclinical studies with clear mechanistic work, multiple models

Rare for Students but Possible

- Randomized controlled trial (often educational)

- Large registry analysis with strong methods

- Sophisticated meta-analysis or systematic review using PRISMA

Be honest. A single-center retrospective study of 180 patients with descriptive stats and a couple of t-tests is not “clinical outcomes research at the level of NEJM.” That does not diminish its value; it just defines its realistic home.

1.2 What is the field and subfield?

Being too broad here kills journal matching.

Not “cardiology.” Instead:

- Interventional cardiology – procedural outcomes / stent techniques

- Heart failure – readmission prevention / GDMT optimization

- Preventive cardiology – risk factor modification / screening

Similarly, not “medical education.” Instead:

- Assessment and evaluation

- Simulation-based training

- Learning environment / mistreatment

- Preclinical curriculum

Write down a one-line label:

“Single-center retrospective cohort of post-op delirium in older vascular surgery patients.”

This line will function as your anchor.

1.3 Who actually cares about these results?

Target decision-makers:

- Does this change bedside clinical practice?

- Does it inform local QI processes?

- Does it guide curriculum design?

- Does it primarily exist to demonstrate productivity?

If the primary relevance is:

- To frontline clinicians → clinical specialty journals

- To educators → medical education journals

- To hospital systems / administrators → quality/safety journals

- To students / trainees → education-focused trainee journals or sections

1.4 What is the realistic novelty?

Ask your mentor, bluntly: “On a 1–10 scale of novelty (10 = practice-changing NEJM), where does this sit?” Most solid student projects live between 3 and 6.

Your journal tier will track very closely with that number.

2. Define Your Constraints: Career Stage, Timelines, and Needs

Students are not faculty. You have different constraints that must shape journal choice.

2.1 What is your timeline?

Common student scenarios:

Applying to medical school in 6–12 months

You need:- At least acceptance in hand (ideally PubMed-indexed)

- Short review times

- High likelihood of acceptance on first or second attempt

Applying to residency in 6–18 months

You care about:- PubMed indexing for ERAS

- Fast editorial cycles

- Journals known in your target specialty (e.g., applying to neurology: Neurology, Journal of the Neurological Sciences, Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, etc.)

Early in premed or M1–M2 with >2 years before applications

You have:- Flexibility to aim slightly higher

- Time for one or two rounds of rejection and resubmission

Translate your situation into hard constraints:

- “We must have at least early online acceptance before September 15.”

- “We cannot afford a 9–12 month review cycle.”

2.2 What about publication costs?

Students frequently overlook Article Processing Charges (APCs).

You must answer:

- Does your mentor have grant support that explicitly covers APCs?

- Does your institution have open-access agreements with specific publishers?

- Are there trainee discounts or waivers available?

Categories:

Traditional subscription journals

- No APC for standard publication

- Optional open access fee (usually $2,000–$4,000)

- Good for students without funding

Fully open-access journals

- APCs can be high (€1,500–$4,000+)

- Some low-IF / regional journals charge less

- Watch for predatory patterns

Student / trainee journals

- Often no fees

- Variable indexing (some not on PubMed)

You should explicitly decide:

“We will prioritize journals with no mandatory APCs,”

or

“We are willing to pay up to $X if the journal fit and indexing are strong.”

2.3 What do you actually need from this paper?

Be precise:

For medical school admissions:

- PubMed-indexed, any impact factor

- Co-authorship is fine; first-author is a bonus

For competitive residency (e.g., derm, ortho, plastics, neurosurgery):

- First- or second-author matters

- Specialty-relevant journals are more valuable than generic low-tier journals

- Multiple small papers in specialty journals can be better than one “okay” paper in a miscellaneous journal

3. Building a Journal Shortlist: A Concrete Workflow

Now we move from abstract criteria to a stepwise method you can repeat.

3.1 Start with where similar studies are published

You already have your most powerful tool: your own reference list.

Take your:

- Most conceptually similar paper

- Most methodologically similar paper

- Most recently published paper in your topic

Write down the journals of those 5–10 key references. These are your initial candidates.

Then expand systematically:

Use PubMed’s “Similar articles” feature

- Open your closest-match paper

- Click “Similar articles”

- Skim the right sidebar for repeated journal names

Use journal finder tools carefully Most major publishers have them:

- Elsevier Journal Finder

- Springer Journal Suggester

- Wiley Journal Finder

- JANE (Journal/Author Name Estimator) for PubMed

Strategy:

- Paste your abstract

- Note down 5–10 suggested journals that appear reasonable

- Cross-check scope and indexing independently

Ask your mentor for 3–5 realistic targets Not “dream journals.” Realistic ones.

Phrase it as:“Given our study’s design and results, what 3–5 journals do you see as the most realistic first and second submissions?”

Combine these to form a candidate list of about 10–15 journals.

3.2 Screen by scope before anything else

Go to each journal’s website and read:

- “Aims and Scope” section

- Recent table of contents (last 6–12 months)

- Instructions for Authors, especially article types

You are checking:

Do they publish your article type?

- For example, many high-impact journals do not want single-center retrospective studies, small case series, or basic descriptive QI.

Do they publish work with your:

- Topic?

- Population (pediatrics vs adults)?

- Setting (primary care vs tertiary center)?

Concrete example:

You have a curriculum redesign in a first-year anatomy course.

High-field “medical education” journals may prefer multi-institutional data or rigorous randomized designs.

But journals like Anatomical Sciences Education might be an excellent fit.

If you cannot easily find at least 3–5 recent papers that are similar in design and population to your study, de-prioritize that journal.

3.3 Screen by indexing and credibility

For student projects, the minimum standard should usually be:

- Indexed in PubMed / MEDLINE

or - At least in Scopus or Web of Science with solid editorial board and publisher reputation

Verify:

- Use NLM Catalog (for PubMed)

- Check if the journal is listed in COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics)

- Look for affiliation with recognized societies (e.g., American College of Cardiology)

Red flags suggesting predatory behavior:

- E-mail invitations from generic addresses soon after conference presentations

- Promises of “rapid publication within 7 days” with guaranteed acceptance

- Publisher unknown to your mentor

- Poorly formatted website, obvious typos, unclear editorial board

When in doubt, run the journal by:

- Your mentor

- Your institution’s library staff

- The DOAJ’s (Directory of Open Access Journals) whitelist

3.4 Evaluate fit tier instead of just impact factor

Impact factor obsession is common in students and not productive. Think in tiers relative to your study:

Tier 1: Top General / Specialty Journals

- NEJM, JAMA, Lancet

- Specialty flagships: Circulation, Annals of Surgery, Gastroenterology

- Student first-author retrospective single-center studies almost never land here

Tier 2: Strong Specialty Journals / High-quality General Journals

- Good reach in a specific field

- Moderate to high methodological expectations

Tier 3: Solid Niche / Subspecialty Journals

- Often where much real-world practice-relevant data lives

- Many student projects fit here well

Tier 4: Lower-impact / Regional Journals

- Reasonable peer review

- Good for early projects, case reports, QI, small data sets

Map your project:

- Level 3–4 novelty + single-center retrospective + modest N = Aim for Tier 3–4

- Level 6–7 novelty + robust methods + clear clinical impact = You can test a Tier 2 first

The key is: choose a first submission that is ambitious but plausible. Aiming too high can burn 6–9 months of delay with little upside at the student level.

4. Constructing a Tiered Submission Plan

You should not approach journals one at a time without a broader plan. A structured targeting pathway saves you months.

4.1 Build a 3-tier target list

For a typical student project, your matrix might look like this:

Tier A (Reach, but still plausible)

- 1–2 journals

- Slightly above your comfort level

- If accepted, big impact on CV and visibility

Tier B (Realistic primary targets)

- 3–5 journals

- Clear scope match

- Good track record of similar studies

Tier C (Safety / Timely publication)

- 2–3 journals

- Higher acceptance rates

- Reasonable review times

- Good for when deadlines loom (like ERAS submission)

Do this concretely:

Example – M3 student, single-center retrospective on postoperative delirium:

Tier A

- Journal of the American Geriatrics Society

- Anesthesia & Analgesia (if methods robust)

Tier B

- Journal of Clinical Anesthesia

- Aging Clinical and Experimental Research

- Perioperative Medicine

Tier C

- BMC Anesthesiology

- A regional anesthesia or geriatric medicine journal indexed in PubMed

4.2 Time-aware sequencing

Integrate review times into your sequence.

For each journal, look up:

- “Time to first decision”

- “Time from acceptance to online publication”

These are often found in “Journal metrics” or “For authors” sections.

Then plan:

- Submit first to Tier A with moderate review times (≤8 weeks)

- If rejected without review → immediately resubmit to next Tier A/B journal

- If under review but delayed beyond expectations → you may ask for a status update after a reasonable interval (e.g., 10–12 weeks)

When the calendar is critical (e.g., 4–6 months to ERAS):

- You might skip Tier A entirely and start with Tier B/C

- Or move quickly down the tier if first rejection occurs

5. Aligning Manuscript Structure With Target Journal

Journal targeting is not only where you submit. It is also how you shape the manuscript.

5.1 Study exemplar articles

For your top 2–3 target journals:

- Download 3–5 recent articles with similar design

- Analyze:

- Abstract structure: word limits, subheadings

- Introduction length and style

- Methods detail level (concise vs very granular)

- How tables / figures are organized

- Typical length of Discussion

You want your manuscript to feel like it belongs.

For instance:

- Some QI journals strongly prefer explicit use of PDSA cycles, run charts, and SQUIRE guidelines

- Some education journals expect explicit theoretical frameworks (e.g., Kirkpatrick model, cognitive load theory)

5.2 Choose your angle to match the journal’s priorities

The same dataset can be framed differently depending on the journal.

Example:

You studied implementation of a new clinical decision support tool in the ED.

For a health informatics journal:

- Emphasize system design, algorithm, integration challenges, user interfaces

For an emergency medicine clinical journal:

- Emphasize patient outcomes, diagnostic accuracy, ED throughput

For a QI journal:

- Emphasize process changes, PDSA cycles, sustainability

The data does not change. The narrative emphasis does.

Students often undersell their work by presenting a generic “this is what we did” story rather than tailoring the framing to the priorities of the target audience.

6. Special Scenarios: Case Reports, Education Projects, and QI

Student projects cluster in a few patterns that warrant specific targeting strategies.

6.1 Case reports and small case series

These are common in preclinical shadowing and early clerkships.

Targeting rules:

Prefer journals with explicit case-report sections

- BMJ Case Reports

- Journal of Medical Case Reports

- Specialty journals with “Case Reports” or “Clinical Images” sections

Avoid generic low-quality case-report-only journals when possible

Many charge fees, have poor indexing, and add little CV value. Always check:- PubMed indexing

- Publisher credibility

Match the case to the right specialty

A rare rheumatologic manifestation of cancer? Better in a rheumatology or oncology journal than a generic case-report journal.

For case reports, novelty is king:

- Truly first-of-its-kind → aim a bit higher

- Unusual twist on a known condition → mid- to lower-tier specialty journals

6.2 Medical education projects

Very common in students involved in curriculum committees or teaching electives.

Basic rule: education work is often harder to place than students expect. Many reputable education journals want:

- Clear conceptual/theoretical framework

- Rigor in design (comparison groups, valid instruments, multi-year data if possible)

Target options:

Top general med ed journals (Academic Medicine, Medical Education, Medical Teacher)

- Highly competitive

- Strong preference for conceptual innovation and robust methods

Specialty education journals

- Journal of Surgical Education

- Teaching and Learning in Medicine

- Anatomical Sciences Education

- The Clinical Teacher

Institutional / regional education journals

- Often appropriate for single-course, small-sample projects

Again: match the scale and rigor of your education project to the journal’s bar.

6.3 Quality improvement projects

QI is a staple of student and early resident work.

Key: QI publishing requires specific reporting standards:

- SQUIRE guidelines (for reporting QI studies)

Journal families for QI:

- BMJ Open Quality

- American Journal of Medical Quality

- Journal for Healthcare Quality

- Specialty journals with QI sections (e.g., Journal of the American College of Surgeons often runs QI-focused pieces)

If your project:

- Is single-unit, small N, minimal statistical rigor

- But has a clear PDSA cycle and process metrics

Then mid-tier QI or specialty QI sections are usually better fits than top-tier general journals.

7. Protecting Yourself from Predatory and Low-Value Venues

Students are prime targets for predatory publishers because you are eager to have “a publication” and often unfamiliar with the landscape.

Concrete defense checklist:

Indexing check

- Is the journal in PubMed / MEDLINE or at least Scopus/Web of Science?

- If not, why not? Some newer journals take time, but you need a clear rationale from your mentor to proceed.

Publisher and society affiliation

- Recognized houses (Elsevier, Springer, Wiley, BMJ, JAMA Network, major societies) are generally safe.

- Unknown publisher with hundreds of loosely related journals? Be cautious.

APC transparency

- Clear APC stated on website? Fine.

- APC revealed only after acceptance? Red flag.

Peer-review promises

- “Guaranteed acceptance” or “review within 48 hours” = walk away.

- Reasonable peer-review timeline = weeks, not days.

Website quality

- Typos, broken links, unclear aims, and missing editorial board bios all warrant suspicion.

If you are in doubt, pause. Show the journal to:

- Your PI

- A trusted faculty researcher

- Librarian staff

- Or look for external evaluations (there are lists of predatory publishers, though they are not perfect)

Publishing in a clearly predatory journal:

- Weakens the value of your work

- May be questioned in competitive residency reviews

- Is almost never necessary when there are legitimate lower-tier options

8. Practical Workflow: From Draft to Submission Decision

Let us pull the pieces into an operative checklist.

Step 1: Internal project classification

- Design, field, audience, novelty rating (1–10)

- Record in 2–3 sentences

Step 2: Constraints assessment

- Timeline requirements (applications, graduation)

- Funding / APC constraints

- Desired indexing and audience (specialty vs general)

Step 3: Journal candidate generation

- From your reference list

- From “Similar articles” in PubMed

- From mentor suggestions

- From journal finder tools

Step 4: Aggressive culling by scope and credibility

For each candidate:

- Scope match (Y/N)

- Similar recent articles present (Y/N)

- PubMed / major indexing (Y/N)

- Predatory red flags (Y/N)

Eliminate weak matches.

Step 5: Build your tiered list

- Tier A: 1–2 stretch journals

- Tier B: 3–5 primary targets

- Tier C: 2–3 safety / time-sensitive options

Record:

- IF (approximate)

- Indexing status

- APC policy

- Median review times

Step 6: Manuscript tailoring

- Choose your first target

- Format manuscript to that journal’s style

- Align narrative angle with journal’s typical emphasis

- Strictly follow Instructions for Authors (word counts, abstract format, reference style)

Step 7: Submission and contingency planning

Before clicking submit:

- Decide: If rejected, what is the next journal?

- How fast will we resubmit? (Goal: within 1–2 weeks)

- Are there any journal-specific quirks (e.g., structured cover letter requirements)?

When decision returns:

Desk rejection (no external review):

- Use editor comments to refine scope/angle

- Move down to next journal without delay

Rejection after review:

- Extract all actionable feedback

- Improve manuscript significantly before resubmission

- Do not just change the journal name and resubmit unchanged

You want each submission cycle to increase the manuscript quality and fit.

FAQs (Exactly 6)

1. How low in impact factor is “too low” for a student publication to still help for medical school or residency?

There is no universal cut-off. For most medical school admissions, any PubMed-indexed original article—regardless of impact factor—is meaningful. For competitive residencies, a 0.5–2 impact factor in a relevant specialty journal can be more useful than a slightly higher impact factor in a non-clinical, obscure field. Extremely low IF in non-indexed or predatory journals is far less valuable and sometimes detrimental. The main thresholds: PubMed indexing, journal legitimacy, and specialty relevance.

2. Should students ever aim directly for top-tier journals like NEJM or JAMA?

Only in very rare situations: truly practice-changing data, multicenter collaborations, or highly novel systematic reviews with senior coauthors who routinely publish there. Most student projects are better served by strong specialty or mid-tier journals where the work fits naturally. Submitting to NEJM with a small single-center retrospective study burns time and offers almost no realistic upside at the student level.

3. Is it better to publish in a non-indexed student journal quickly or wait longer for a PubMed-indexed journal?

If you are early in training (premed, M1) and the paper is largely for experience, a reputable student journal can be reasonable. However, for residency applications, PubMed-indexed publications carry far more weight. When time allows, prioritize indexed journals. When deadlines are tight and options limited, weigh that single non-indexed publication against the potential to develop a stronger, indexable project instead.

4. How many journals should I realistically plan on submitting to the same paper?

Most projects find a home within 1–4 submissions if the targeting is rational and the manuscript improves each cycle. If you are beyond 4 rejections, it is time to ask whether the core project is too weak, misframed, or inappropriate for journal publication (some QI projects, small educational initiatives, or limited case reports may fit better as local reports or conference abstracts only).

5. What if my mentor insists on a target journal I think is unrealistic?

Frame the conversation around data, not feelings. Bring: (1) recent articles from that journal showing typical study design and scale; (2) your project classification; and (3) a tiered list with alternative options. Ask, “Given that our study is X and these published papers are Y, do you see this as Tier A (reach) or Tier B (realistic)? And if we are rejected, can we agree to promptly move to Journal B?” Most mentors respond well to structured reasoning, especially when you connect it to your application timelines.

6. How do conference abstracts and posters fit into this journal targeting strategy?

Think of conference presentations as an intermediate validation step. Present at a relevant specialty or education conference first when possible. Use audience questions and feedback to refine your manuscript and clarify which journals your work resonates with. High-quality conferences also give hints: where do similar presenters publish full articles later? Track those journals, then integrate them into your Tier B list. Do not treat posters as the endpoint if your study is robust enough for full publication.

With a structured targeting strategy in hand, you are no longer just “hoping” a journal will take your paper. You are matching the right project to the right home, on timelines that serve your career rather than sabotage it.

Once you have done this for 2–3 projects, the process becomes second nature. Then the real leverage begins: aligning your very choice of future projects with the journals and audiences that will matter most for your specialty goals. But that strategic project selection—that is the next step in your research journey.