Most student-authored response letters fail not because the science is weak, but because the reply is disorganized, defensive, or unclear.

Let me show you exactly how to avoid that.

Medical students and premeds are publishing earlier and more often. That is good for your career. What usually blindsides first-time authors is not the writing of the paper. It is the response to reviewer comments.

You get the decision email. “Major revisions.” Three reviewers. Pages of comments. Some contradictory. Some you do not fully understand. Some that feel unfair.

This is where many student authors lose time, credibility, and sometimes the acceptance.

Below is a concrete, line-by-line template and strategy for crafting a professional, reviewer-ready response letter that academic editors recognize immediately as “competent and serious.”

The Core Principles Before You Touch the Keyboard

(See also: Basic Biostatistics for Student Researchers for essential statistical methods.)

Before format, before wording, you need the right mindset. There are three non-negotiables:

Gratitude without groveling

You acknowledge the reviewer’s time and effort briefly and professionally. You do not write a love letter. One or two sentences per reviewer section is enough.Non-defensive posture

You never argue from emotion (“We strongly disagree with the reviewer’s harsh critique”). You argue from data, logic, or constraints (“Given the small sample size, subgroup analyses would be statistically underpowered and potentially misleading”).Radical clarity

The editor and reviewers should be able to:- Find each comment quickly

- See exactly how you changed the manuscript

- Understand why you did or did not follow a suggestion

You are not just answering questions. You are showing that you understand the norms of scientific discourse.

The High-Level Structure of a Response Letter

Your response letter should almost always follow this structure:

- Header and basic information

- Global introductory paragraph to the editor

- Per-reviewer sections, each with:

- Reviewer’s original comment (or a clear paraphrase)

- Your response

- Location of changes in the manuscript

- Optional final closing note

Let me break this down in concrete detail.

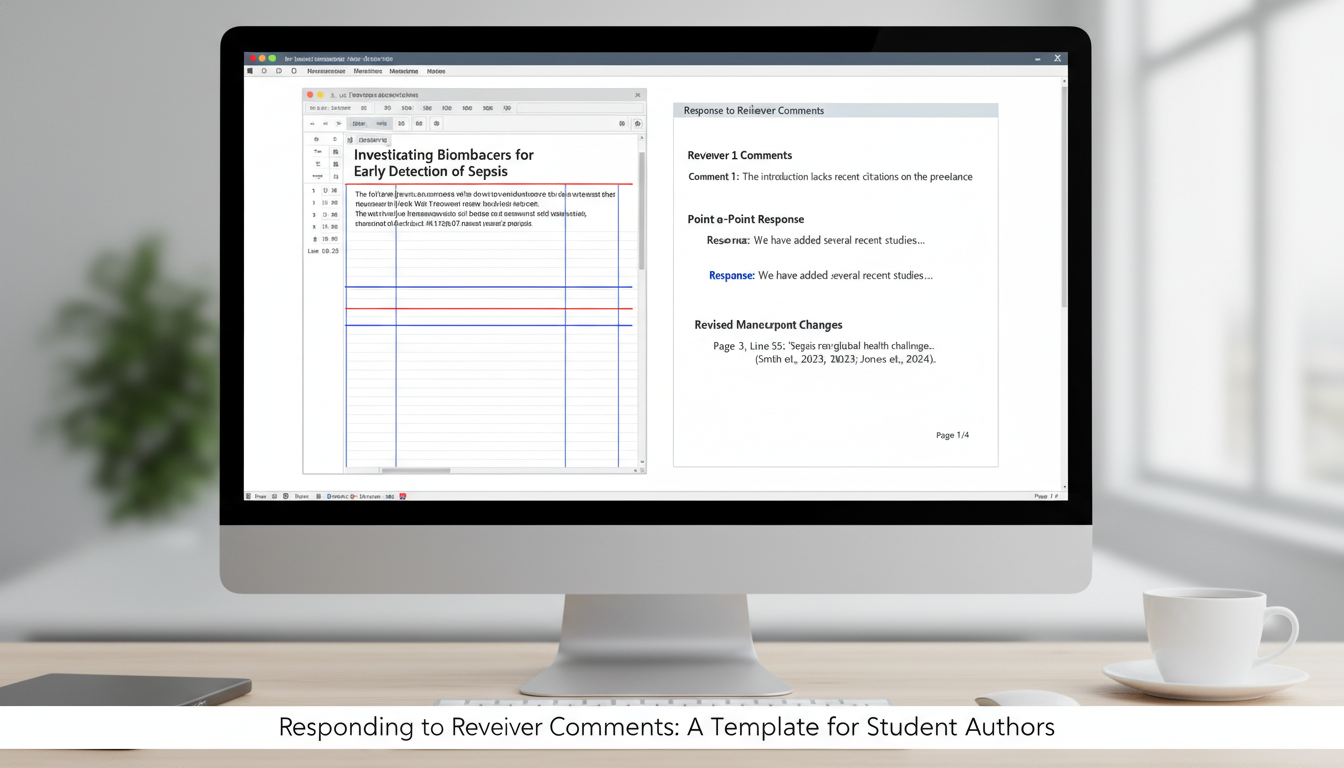

Step 1: The Header and Basic Info

Your response document is a separate file, usually titled something like:

“Response_to_Reviewers_ManuscriptID_XXXX.docx”

At the top of the document:

Manuscript Title: [Exact title of your manuscript]

Manuscript ID: [As assigned by the journal]

Journal: [Journal name]

Authors: [First Author et al.]

Corresponding Author: [Name, email]

Response to Reviewers’ Comments

This looks trivial. It is not. A clean header signals to the editorial team that you understand basic publishing conventions. Sloppy or missing headers ring small alarm bells.

Step 2: The Global Introductory Paragraph

Right under the header, you include a short, diplomatic introduction addressed to the editor, not the reviewers.

Here is a proven template you can adapt:

Dear Dr. [Editor’s Last Name] and Reviewers,

We thank you for the careful review of our manuscript and the constructive comments provided. We have revised the manuscript accordingly and believe that the changes have strengthened the work. Below, we respond to each comment point-by-point. For clarity, reviewers’ comments are repeated in italics, followed by our responses. All changes are indicated in the revised manuscript, and key modifications are noted with page and line numbers.

Key points:

- Avoid effusive praise (“We are extremely grateful for the outstanding insights of the reviewers”). One or two sentences is enough.

- Define your formatting convention here: italics for reviewer comments, regular font for responses, etc.

- Promise specific page/line references. Then deliver.

Some journals now use continuous line numbering in manuscripts. If so, match their format. If they only refer to sections and paragraphs, mirror that.

Step 3: Structuring by Reviewer

Always separate responses by reviewer. Use clear headings:

Reviewer #1:

[comments and responses]

Reviewer #2:

[comments and responses]

Reviewer #3:

[comments and responses]

Under each reviewer, you work comment by comment. Never merge different reviewers’ issues into one blended section. Editors hate that.

Also, do not skip any comment. Even “minor” ones like spelling or reference style get a one-line acknowledgment and a note that it was corrected.

Step 4: The Comment-Response Template (Core Pattern)

Here is the exact micro-template you will reuse for each point. After some practice, it becomes automatic.

Formatting convention (recommended):

- Reviewer comment: italicized, prefaced with “Comment:”

- Your response: standard font, prefaced with “Response:”

- Some authors also bold their own actions for quick scanning

Generic template

Comment 1: [Copy-paste or paraphrase the reviewer’s comment here.]

Response: Thank you for this helpful suggestion. We have [briefly state what you did in response]. The manuscript has been revised on page X, lines Y–Z to [add/clarify/correct] [specific element].

[Optional: Provide additional justification, data, or explanation if needed.]

Keep that structure consistent. Let us walk through realistic examples at different difficulty levels.

Step 5: Easy Wins – When You Agree and the Fix Is Straightforward

These are spelling errors, missing references, minor clarifications. Do not overcomplicate them.

Example 1: Simple textual clarification

Comment 2: The introduction is somewhat brief. Please provide additional context on prior work in this area, particularly regarding outpatient telemedicine in pediatrics.

Response: We appreciate this suggestion. We have expanded the introduction to provide more context regarding prior studies of outpatient pediatric telemedicine, including Smith et al. (2020) and Rahman et al. (2021). The manuscript has been revised on page 3, lines 45–60 to reflect these additions.

Note:

- You explicitly say what you did.

- You provide page/line references.

- You mention at least one concrete addition (e.g., references).

Example 2: Typo or style

Comment 3: There are several minor typographical errors (e.g., “hypertention” should be “hypertension”). Please proofread carefully.

Response: We thank the reviewer for noting these errors. We have carefully proofread the manuscript and corrected the identified typographical errors, including “hypertention” to “hypertension” (page 5, line 112) and several others throughout.

You do not list every tiny correction, but you confirm it has been done and provide at least one concrete example.

Step 6: Moderate Complexity – When You Need to Add Analyses or Substantive Clarifications

These are the comments that often improve your paper. They also take work: new tables, subgroup analyses, clearer descriptions.

Example: Request for additional analysis

Comment 4: Please consider providing a subgroup analysis by sex, as outcomes may differ between male and female participants.

Response: We agree that examining potential sex differences is valuable. We have performed additional analyses stratifying outcomes by sex. These results are now reported in the Results section (page 9, lines 190–210) and summarized in a new Table 3. In brief, we found no statistically significant differences in the primary outcome between male and female participants (p = 0.27), though female participants had slightly higher satisfaction scores (mean difference 0.4 on a 5-point scale, p = 0.04).

The Methods section has also been updated to describe this subgroup analysis (page 6, lines 120–128).

Key elements:

- Acknowledge the value of the suggestion.

- State explicitly that you conducted the analysis.

- Provide a short “headline result.”

- Indicate exactly where in the manuscript this appears.

Example: Clarifying methodology

Comment 5: The description of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is unclear. Please clarify whether patients with prior myocardial infarction were excluded.

Response: We appreciate this important point and agree that our initial description lacked clarity. Patients with a history of prior myocardial infarction were indeed excluded from the study. We have revised the Methods section (page 5, lines 95–102) to clarify this criterion as follows: “Participants were excluded if they had a documented history of prior myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, or significant valvular disease.”

Notice that inserting a direct quote from the revised text can be extremely helpful, especially when the clarification is key.

Step 7: Hard Cases – When You Disagree or Cannot Do What Is Asked

This is where many student authors make critical errors.

You are allowed to disagree with a reviewer. You are not allowed to be dismissive, vague, or emotional. Even if the reviewer is partly wrong, assume the burden is on you to explain your constraints.

General structure when you disagree

- Acknowledge the importance of the issue.

- State clearly that you did not make the requested change, and why.

- Offer a reasonable compromise (e.g., add a limitation or brief explanation).

Example: Request for infeasible new data collection

Comment 6: The follow-up period is relatively short. The authors should extend the follow-up to 12 months to assess long-term outcomes.

Response: We agree that longer-term follow-up would provide valuable information. However, extending follow-up to 12 months is not feasible for this dataset because data collection concluded in June 2023 and the study protocol did not include additional follow-up visits beyond 6 months. We have therefore not extended the follow-up period.

To address this limitation more explicitly, we have revised the Limitations section (page 14, lines 300–308) to emphasize the restricted follow-up duration and to note that long-term outcomes should be evaluated in future studies.

You are transparent about the constraint. You strengthen your limitations. You do not pretend the issue does not exist.

Example: Methodological criticism you partly reject

Comment 7: The authors should use multivariable logistic regression rather than the current unadjusted analyses, which are inadequate.

Response: We appreciate the reviewer’s focus on appropriate statistical methodology. We agree that adjustment for key covariates is important to reduce confounding. In the original submission, we used multivariable linear regression for our primary continuous outcome (systolic blood pressure). Logistic regression would require dichotomizing this variable, which could reduce statistical power and obscure clinically relevant variation.

To address the concern about adjustment, we have clarified the statistical approach in the Methods section (page 7, lines 140–155) and have added adjusted analyses for our secondary binary outcome (hypertension control at 6 months), which are now reported in Table 4. These models adjust for age, sex, baseline blood pressure, and comorbid diabetes. We believe this approach balances the reviewer’s concern about confounding with preservation of information in our primary continuous outcome.

You are not simply saying “no”. You are showing that you considered the comment carefully and implemented what you reasonably could.

Step 8: Handling Contradictory or Conflicting Reviewer Comments

Classic problem: Reviewer 1 wants more detail. Reviewer 2 wants the paper shorter. Reviewer 3 wants a different analytic approach than Reviewer 2. You cannot fully satisfy everyone.

Here is the strategy.

Identify conflicts explicitly in your internal planning, not necessarily in the letter yet. Mark them with notes: R1 vs R2.

Choose a defensible middle path based on:

- Journal word limits

- Editorial priorities (editor’s cover letter can hint at this)

- Scientific coherence

Communicate carefully when addressing each reviewer separately.

Example: Word count vs. additional details

Reviewer 1: “Please add more detail to the Methods section on recruitment and randomization.”

Reviewer 2: “The manuscript is too long; consider shortening the Methods.”

You might respond to Reviewer 1 like this:

Comment 3 (Reviewer 1): The description of recruitment and randomization is too brief. Please add further detail on how participants were approached and randomized.

Response: We thank the reviewer for this suggestion and agree that additional detail improves transparency. We have expanded the Methods section (page 4, lines 80–96) to describe the recruitment process and randomization procedure in more detail. To accommodate this within the journal’s word limits, we have shortened some less critical descriptive text in the Introduction and Discussion.

To Reviewer 2:

Comment 2 (Reviewer 2): The manuscript is somewhat lengthy. Consider shortening the text, particularly in the Introduction and Methods.

Response: We appreciate this comment. In revising the manuscript, we have reduced less essential background material in the Introduction (page 2, lines 30–45) and streamlined portions of the Discussion (page 13, lines 270–290), resulting in a net reduction in word count. At the same time, we have slightly expanded the Methods to clarify the recruitment and randomization procedures, which we view as essential for reproducibility.

You do not mention other reviewers by name. You show that you balanced competing priorities while respecting the journal’s constraints.

Step 9: Tone and Phrasing – What To Say and What To Avoid

Students often ask for “stock phrases.” Here are practical ones that work, and also phrases that undermine you.

Useful phrases

- “We thank the reviewer for this helpful/insightful/specific comment.”

- “We agree that this is an important issue…”

- “We have now clarified this point by…”

- “We have added the following text…”

- “We regret the lack of clarity in the previous version and have revised…”

- “We agree in principle with the reviewer’s suggestion; however, due to [specific reason], we were unable to [specific request]. Instead, we have [reasonable alternative].”

Phrases to avoid

- “We strongly disagree…” (use “we respectfully disagree” if needed)

- “As already stated clearly in the manuscript…” (implies the reviewer missed something)

- “We do not think this is necessary.” (always explain why)

- “This is beyond the scope of our paper.” (on its own; if used, immediately explain scope and offer at least a limitation statement)

You can be firm. You cannot be dismissive.

Step 10: Using Color, Bold, and Tracking – Formatting Choices

Most response letters are plain text, but you can use formatting intelligently to increase clarity. For example:

- Italics: reviewer comments

- Regular: responses

- Bold: key modifications or section names

Example snippet:

Comment 8: Please state whether the study was approved by an institutional review board (IRB).

Response: We thank the reviewer for pointing out this omission. We have added the following sentence to the Methods section (page 5, lines 100–104): “This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of [Institution Name] (Protocol #2023-0145), and all participants provided written informed consent.”

Do not use multiple colors, random highlighting, or tracked changes in the response document itself unless the journal specifically requests it. Tracked changes go in the manuscript file, not here.

Step 11: Cross-Referencing Manuscript Revisions

Strong response letters make it easy for reviewers to confirm changes.

Always include:

- Page numbers in the revised manuscript

- Line numbers if available (many journals ask you to enable line numbering)

- If sections are restructured significantly, reference section titles too

Example:

“…The Methods section has been revised on page 6, lines 130–142 (Statistical Analysis subsection) to describe the mixed-effects model approach in more detail.”

When you introduce new tables or figures:

“…These results are now presented in a new Table 2 and briefly described in the Results section (page 8, lines 175–188).”

If you delete a section entirely due to a reviewer comment, say so:

“…In response, we have removed the paragraph discussing national policy implications, as suggested. This deletion occurs on the former page 12, lines 250–262 of the original manuscript.”

Step 12: The Final Check – Internal Workflow for Student Authors

For premeds and medical students, this is usually a team sport. Here is a practical workflow you can follow with your mentor or co-authors.

Export all reviewer comments into a working document

- Copy-paste each comment, grouped by reviewer

- Number them sequentially (Reviewer 1 – Comment 1, 2, 3…)

- This becomes your response skeleton

Triage comments

- “Easy” (typos, small clarifications)

- “Moderate” (new text, limited analyses)

- “Hard” (new data, major analytic changes, conceptual disagreements)

Assign work

- Methods/statistics to someone comfortable with analysis

- Clinical interpretation to the mentor or more senior co-author

- Basic editing and uniform phrasing to the first author (often the student)

Draft responses in the response document as you make changes in the manuscript

Do not try to modify the manuscript and then back-fill the response letter. You will forget details, and inconsistencies will creep in.Have one person (often the PI) read only the response letter once

They should ask: “If I were a reviewer, could I see quickly what has changed and why?”

Editors sometimes skim the response letter first before re-reading the revised manuscript.Do a final alignment pass

- Every response that says “we have added…” should correspond to an actual visible change.

- Page/line numbers match the latest version (after any last-minute edits).

This process feels tedious the first time. It becomes second nature.

A Complete Mini-Example: Putting It All Together

Here is a condensed example for a hypothetical short paper, so you can see flow and tone.

Reviewer #2

Comment 1: The abstract does not mention the primary outcome measure. Please specify it clearly.

Response: We thank the reviewer for this observation and agree that the primary outcome should be stated explicitly in the abstract. We have revised the abstract (page 1, lines 20–25) to include the following: “The primary outcome was change in systolic blood pressure at 6 months.”

Comment 2: The sample size seems small (n=72). Please provide a power calculation or justify the sample size.

Response: We appreciate this important point. As this was a pilot study conducted within a single academic clinic, the sample size was determined by the number of eligible participants available during the study period rather than a formal a priori power calculation. We have clarified this in the Methods section (page 5, lines 90–98). We have also added a statement to the Limitations section (page 13, lines 265–272) acknowledging the limited sample size and its potential impact on statistical power.

Comment 3: The discussion overstates the generalizability of the findings. Please temper the conclusions.

Response: We agree with the reviewer and have modified the Discussion to temper our conclusions. Specifically, we have removed the sentence suggesting that our findings are “likely applicable to most primary care settings” and instead state that “our findings may be most relevant to similar academic primary care clinics” (page 12, lines 240–248). We have also expanded the Limitations section to emphasize the single-center design.

Notice: each answer is specific, polite, and concretely linked to manuscript changes.

What This Means For You as a Student Author

Responding to reviewer comments is not busywork. It is where you learn the language and norms of academic medicine.

Premed and medical students who master this skill:

- Impress faculty mentors and often get invited onto future projects.

- Learn rigorous self-critique of their own research.

- Feel far less intimidated by peer review on subsequent papers.

Treat each response letter as a training exercise in clear scientific communication.

FAQ (exactly 4 questions)

1. Should I always copy-paste the full reviewer comment, or can I summarize it?

If the comment is short and clear, copy-pasting verbatim is usually best. For very long, multi-part comments, you can break them into sub-comments and paraphrase for clarity, but keep the reviewer’s intent intact. Do not distort or selectively edit comments to make them seem weaker. Some reviewers will compare your quoted text against their original comment.

2. How long is too long for a response letter?

There is no strict word limit, but you should aim for concise, direct answers. For a typical original research article with 2–3 reviewers, response letters of 3–8 pages are common. Extremely short letters often indicate superficial changes; extremely long ones (>15 pages) usually reflect unfocused, overly defensive writing. Focus on clarity rather than hitting a target length.

3. What if a reviewer seems clearly wrong about a factual point?

Assume miscommunication before assuming incompetence. First, check whether your manuscript was ambiguous. Then respond respectfully: clarify the fact, show where the clarification has been strengthened in the text, and avoid any implication that the reviewer “should have” understood. For example: “We regret that our description was unclear. Our study did exclude patients with prior stroke; we have now clarified this point in the Methods (page X, lines Y–Z).”

4. Can I ask my mentor or PI to rewrite my responses?

You should absolutely involve your mentor or PI, especially for complex methodological or interpretive comments. However, you should draft the initial responses yourself. This is how you learn. Then, ask your mentor to review and refine your wording and logic. Senior authors expect to shape the final letter, but they also expect the first author—even a student—to engage deeply with the reviewers’ critiques.

Key takeaways:

- Use a clear, consistent comment–response structure with explicit page/line references.

- Maintain a respectful, non-defensive tone even when you disagree, and always explain your reasoning.

- Treat the response letter as part of the scientific record—it demonstrates your maturity as a researcher just as much as the manuscript itself.