Most medical education research done by students is far too obsessed with multiple‑choice test scores.

If you want your project taken seriously by educators, journals, or residency program directors, you must think beyond “we gave a quiz before and after, and the scores went up.” That design is easy. It is also weak, overused, and often unpublishable without something more.

Let me break this down specifically: as a premed or medical student, you can absolutely do rigorous, meaningful MedEd research. But you need the right mental models of study design, outcomes, and feasibility at your level.

(See also: Basic Biostatistics for Student Researchers for essential statistical concepts.)

Why “MCQ Scores Went Up” Is Not Enough

Here is the usual student project:

- Create a new teaching session or module

- Give a pre‑test (10 MCQs)

- Deliver the session

- Give a post‑test (same or similar MCQs)

- Show that scores improved

- Declare victory

This design (one‑group pretest–posttest) is:

- Vulnerable to testing effects (students do better simply because they saw the questions before)

- Vulnerable to maturation (students learn from other sources in the interval)

- Poor at showing causality (was it your intervention or just time and exposure?)

- Focused only on short‑term knowledge, usually at the lowest level of Bloom’s taxonomy

Yet students keep repeating it because:

- It is easy to execute

- Software (Qualtrics, Google Forms, LMS quizzes) makes it simple

- Faculty often suggest it lazily as a default

- It feels “quantitative” and objective

The solution is not to abandon quantitative data. The solution is to think more strategically about study design and outcome selection, and to pair quantitative with qualitative or richer outcomes where possible.

Core Outcome Frameworks: What Exactly Are You Measuring?

Before choosing a design, you must be explicit about what type of change you are trying to capture.

Two frameworks matter most in MedEd:

- Kirkpatrick (adapted for health professions)

- Miller’s Pyramid

1. Kirkpatrick’s Levels in Health Professions Education

For medical education, Kirkpatrick is usually framed as:

Reaction

- Learner satisfaction, engagement, perceived usefulness

- Example: “I found this simulation valuable” (Likert surveys, focus groups)

Learning

- Knowledge, skills, attitudes gained

- Example: MCQ scores, OSCE station performance, checklists, attitude scales

Behavior

- Change in what learners actually do in clinical settings

- Example: Rate of appropriate antibiotic choice on the wards; hand hygiene compliance

Results

- Impact on patients, systems, or population health

- Example: Reduced central line infections; shorter length of stay; fewer medication errors

Student projects usually stay at Level 1 (satisfaction) and Level 2 (knowledge). That is acceptable, but if you want a more compelling study, you should either deepen Level 2 (better measures) or move toward Level 3 (behavior).

2. Miller’s Pyramid: From Knowledge to Action

Miller’s Pyramid breaks performance into:

- Knows – factual knowledge (MCQs, SAQs)

- Knows how – application (problem‑solving items, script concordance)

- Shows how – demonstration in controlled settings (OSCEs, simulations)

- Does – actual performance in real practice (chart reviews, workplace‑based assessment)

Your study should explicitly target where on this pyramid your intervention operates.

For example:

- A spaced‑repetition module on ECG interpretation is probably “Knows / Knows how.”

- A new ultrasound boot camp may reach “Shows how.”

- A stewardship curriculum with prescribing audits could approach “Does.”

When you anchor your design to these frameworks, you start seeing outcomes beyond “20‑item multiple‑choice test.”

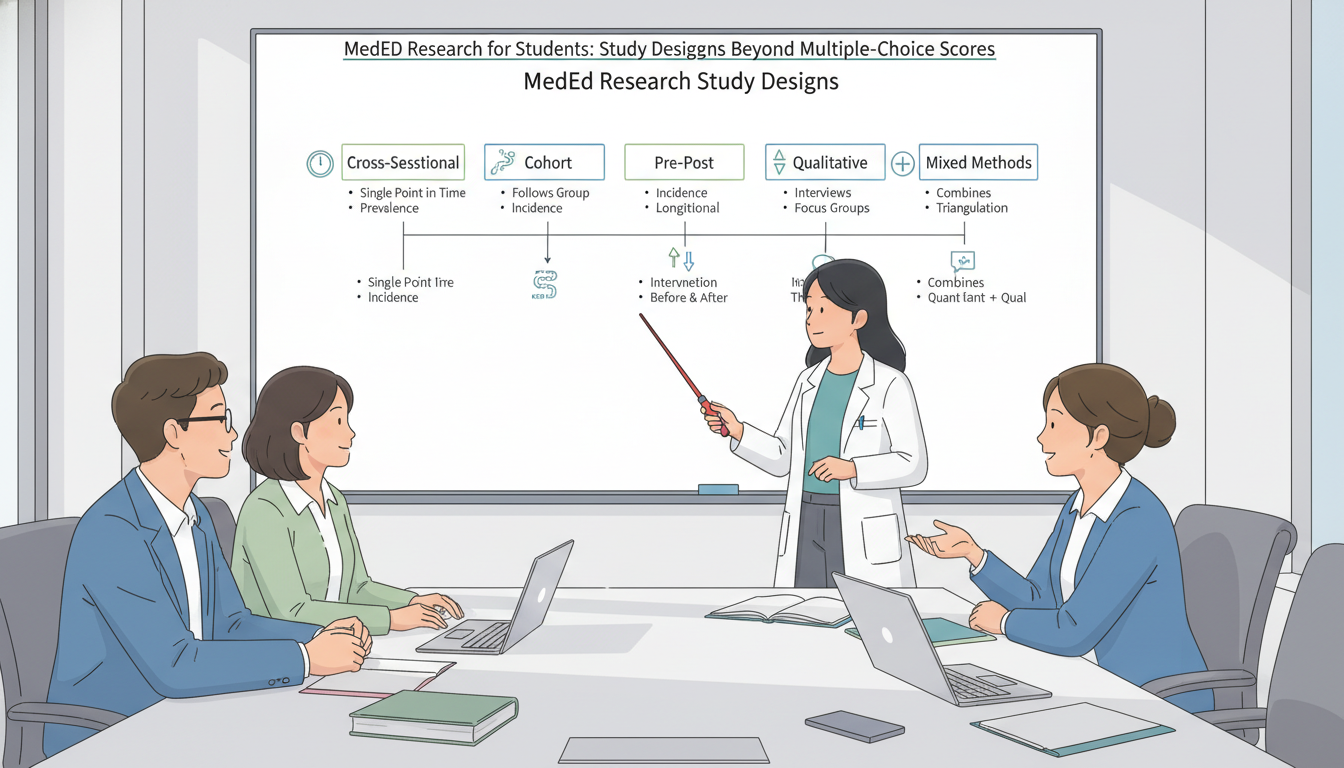

Core MedEd Study Designs Students Can Actually Do

Let us walk through designs that are realistic for premeds and medical students, their strengths, and when to use them. I will organize them by question type, not by textbook categories, because that is how you will think in practice.

1. “What Is Going On Here?” – Descriptive / Cross‑Sectional Studies

Typical student question:

“How are students currently preparing for Step 1 / OSCEs / anatomy, and how does that relate to their well‑being or performance?”

Design: Cross‑sectional survey

- Population: One or more classes (e.g., all M2s at your school)

- Data: One‑time survey with demographics, behaviors, attitudes, and possibly self‑reported performance or objective grades from records

When it works well:

- Early‑phase projects

- Establishing baseline practices before an intervention

- Generating hypotheses for later longitudinal or interventional work

Key design upgrades beyond basic surveys:

- Use or adapt validated scales:

- Burnout: Maslach Burnout Inventory–Student Survey (MBI‑SS) or Oldenburg Burnout Inventory

- Grit, resilience, self‑efficacy, test anxiety – many validated tools exist

- Include non‑score outcomes:

- Time distribution among resources (e.g., Anki vs. question banks vs. lectures)

- Sleep duration, exercise frequency

- Perceptions of curriculum quality

- Avoid only self‑reported grades. Try to:

- Obtain de‑identified actual exam scores from the registrar or course directors

- Use categories (e.g., quartiles) if raw scores cannot be shared

Example project idea:

Study habits, cognitive load, and symptoms of burnout among first‑year medical students during the anatomy block: a cross‑sectional survey correlating study strategies with M1 anatomy practical performance.

No intervention. No pre/post. Still publishable if done rigorously with good sampling, validated instruments, and a clear conceptual model.

2. “Does This New Educational Thing Seem to Work?” – Pretest/Posttest Variants That Are Actually Defensible

You will probably do at least one pre/post study. The point is not to avoid them; it is to strengthen them.

a. One‑group pretest–posttest (the basic model)

This is the familiar design:

- All students take a pretest

- You deliver an intervention (e.g., workshop, module, simulation)

- All students take a posttest

- You compare scores

Alone, this design is weak. But you can improve it substantially.

Key upgrades:

Add delayed posttest

- Posttest immediately after intervention (short‑term learning)

- Second posttest weeks or months later (retention)

- Now your outcome is not just “learning,” but “learning and retention”

Use different but equivalent items

- Avoid reusing identical questions

- Create two item sets mapped to the same learning objectives and difficulty

Include non‑knowledge outcomes

- Self‑efficacy or confidence using validated or carefully designed Likert scales

- Behavioral intentions (“I plan to use X strategy on clinical rotations”)

Employ item analysis

- Do not only report total score change

- Examine item difficulty and discrimination

- Show that poorly performing items or content gaps improved

Report effect sizes, not just P‑values

- Cohen’s d for pre/post difference

- Confidence intervals around mean change

Example:

A flipped‑classroom module in renal physiology: Immediate and 6‑week delayed impact on application‑level MCQ performance and self‑efficacy.

Still simple, but conceptually sharper and more publishable than “scores went from 60% to 75%, P < 0.001.”

b. Non‑equivalent comparison group design (“quasi‑experimental”)

If you can identify a natural comparison group, your study improves dramatically.

Options:

- Compare two cohorts in time:

- Class of 2026 did traditional lectures

- Class of 2027 experiences a new team‑based learning (TBL) format

- Compare parallel groups:

- One campus introduces mandatory simulation

- Another campus retains usual teaching

Threats to validity:

- Groups differ at baseline (prior GPA, MCAT, demographics, curricular changes)

- Unmeasured confounders (different faculty, schedules, external exam timing)

Mitigations:

- Collect baseline characteristics and adjust using:

- Multiple regression

- Stratification

- Propensity scores if sample size permits

- Ensure outcome measurements are the same across cohorts

This is still within reach for a student, especially if you partner with a course director tracking longitudinal scores.

3. “How and Why Does This Work?” – Qualitative and Mixed‑Methods Designs

If you only remember one thing from this article, let it be this: some of the most publishable and impactful student MedEd projects are qualitative or mixed‑methods, not just numerical.

a. Pure qualitative designs

Typical questions:

- How do first‑year students experience the transition to gross anatomy?

- What barriers do students face in using practice questions effectively?

- How do premeds conceptualize “clinical reasoning” before entering medical school?

Common student‑friendly qualitative designs:

- Focus groups (6–8 students per group)

- Semi‑structured individual interviews

- Open‑ended survey responses with systematic analysis

Core steps:

- Develop an interview/focus group guide linked to your research questions.

- Obtain IRB approval and informed consent.

- Record and transcribe (human or software with verification).

- Code using thematic analysis or content analysis:

- At least two independent coders

- Codebook with definitions

- Iterative refinement of themes

- Use software (NVivo, ATLAS.ti, Dedoose) or even Excel if resources are limited.

Why this is powerful for students:

- Sample sizes of 15–30 participants can still yield rich and valid findings.

- No need for large N, randomization, or advanced statistics.

- Depth over breadth: you are generating theory and understanding.

Example:

“I Thought I Was Ready”: A qualitative exploration of cognitive overload and identity shift among first‑year medical students during anatomy.

No MCQ scores. Still legitimate, potentially high‑impact MedEd scholarship.

b. Mixed‑methods: the sweet spot

Mixed‑methods = combining quantitative and qualitative data in a planned way.

Classic patterns:

- Explanatory sequential:

- Phase 1: Quantitative (e.g., pre/post knowledge, survey)

- Phase 2: Qualitative to explain surprising or nuanced findings

- Exploratory sequential:

- Phase 1: Qualitative to explore a phenomenon

- Phase 2: Quantitative to measure and test derived hypotheses

For students, an explanatory sequential design is usually most feasible.

Example design:

- You introduce a new spaced‑repetition–based pharmacology module.

- Quantitative:

- Pre/post MCQ scores and 3‑month retention

- Self‑efficacy scale for prescribing

- Qualitative:

- Focus groups with a sample of participants exploring:

- How they integrated the tool into their study routines

- Barriers to sustained use

- Perceived impact on clerkship performance

- Focus groups with a sample of participants exploring:

Now your paper can address: “Did it work?” and “How did learners experience and implement it?” Journals favor this depth.

Outcome Measures Beyond Multiple‑Choice Scores

If all your outcomes are MCQ scores and 5‑point Likert “satisfaction,” you are under‑leveraging what is possible.

1. Performance‑Based Outcomes

These align with “Shows how” and “Does” on Miller’s Pyramid.

OSCE station performance

- Global ratings by examiners

- Checklist scores (e.g., completed all steps of insulin teaching)

- Standardized patient ratings of communication

Simulation outcomes

- Time to critical actions (e.g., time to defibrillation in VF)

- Number of team communication failures

- Adherence to ACLS algorithm steps

Workplace‑based assessments

- Mini‑CEX scores before and after a feedback intervention

- EPA (Entrustable Professional Activities) ratings across rotations

For students, accessing OSCE/simulation data requires:

- Early discussion with the assessment office

- Strong attention to de‑identification

- Clear alignment with existing institutional priorities

2. Behavioral Outcomes

These move you toward Kirkpatrick Level 3.

Examples:

- Hand hygiene compliance after an educational campaign

- Rate of guideline‑concordant antibiotic prescriptions after a stewardship curriculum (for senior students or residents)

- Use of structured reflection notes after a professionalism workshop

- Actual weekly question bank usage (from platform analytics) after a session on effective test prep

These behaviors can be:

- Observed directly (checklists, audits)

- Extracted from existing systems (EHR data, LMS logs, app analytics)

3. Affective and Cognitive Outcomes

These capture changes in attitudes, motivation, mindset, and cognitive processes.

Examples:

- Growth mindset about learning medicine

- Tolerance of uncertainty in clinical decision‑making

- Implicit bias awareness or measures

- Motivation types (intrinsic vs extrinsic), using frameworks like Self‑Determination Theory

- Cognitive load during specific learning activities

You can measure these with:

- Validated questionnaires (search the MedEd literature; many exist)

- Carefully designed scales anchored in theory

The key is to connect them to a conceptual model. Do not just throw in a “confidence” scale; specify:

- Confidence in what? (e.g., performing cardiac exam, constructing a problem list)

- Why do you expect the intervention to affect it?

4. Longitudinal Outcomes

Longitudinal outcomes are more challenging for students but very powerful.

Examples:

- Correlation of early reasoning assessments with clinical clerkship grades

- Impact of first‑year ultrasound sessions on third‑year OSCE performance

- Pre‑matriculation boot camp participation and M1 academic trajectories

Feasibility tips:

- Start projects in M1 or early M2 if you want follow‑up into clerkships.

- Partner with an experienced faculty member who has access to longitudinal assessment systems.

- Plan for handoff if you graduate before analysis is complete.

Matching Design to Your Training Level and Constraints

Ambition must meet reality. A well‑executed modest study is more valuable than a grand design that collapses.

Let us match realistic medals to stages.

For Premeds

Typical constraints:

- Limited access to internal exam data

- Shorter project timelines

- Less exposure to clinical performance measures

Feasible designs:

- Cross‑sectional surveys of premed peers about study strategies, shadowing experiences, or perceptions of readiness for clinical exposure

- Qualitative interviews exploring how premeds conceptualize empathy, professionalism, or “doctoring”

- Collaboration on existing faculty MedEd projects as a data collector or coder

Key: Aim for strong methodology, even if the scope is narrow. A tightly executed qualitative study on premed perceptions of anatomy or clinical exposure can be quite publishable.

For Pre‑Clinical Medical Students (M1–M2)

You now have:

- Access to internal courses and assessments

- Exposure to OSCEs, simulations, small groups

- Some continuity over 1–2 years

Feasible and strong designs:

- Pre/post with delayed posttest for new workshops or modules

- Mixed‑methods evaluating curricular pilots (e.g., a new peer‑teaching program)

- Qualitative focus groups about hidden curriculum, assessment stress, or learning environments

- Retrospective analyses of exam performance linked to participation in optional review sessions or resources

Seek early alignment with course/clerkship leadership. If your project helps them answer questions they already care about (e.g., “Does this new flipped format help lower‑performing students?”), they will open doors for data access.

For Clinical Students (M3–M4)

Now you can realistically reach into behavior and workplace performance.

Feasible upgrades:

- Chart audits or EHR queries tied to an educational intervention (e.g., VTE prophylaxis adherence after a teaching module)

- Workplace‑based assessment analysis (Mini‑CEX, direct observation tools) before/after feedback training

- Rotation‑level mixed‑methods: e.g., impact of a near‑peer teaching program on both tutors and tutees

Remember you may rotate away or graduate, so:

- Front‑load protocol and IRB work

- Document your data dictionary and analysis plan

- Prepare to hand off or finalize early

Common Design Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Let me be blunt about the patterns that make MedEd reviewers roll their eyes.

1. “We Asked Students If They Liked It” – And That Was It

Satisfaction is:

- Subjective

- Easily biased by grades, charisma of instructor, or novelty

- Weak evidence of learning

If you must include satisfaction:

- Pair it with at least one learning or behavioral outcome

- Use it to interpret rather than to justify the educational approach

2. Underpowered Quantitative Studies

You survey 40 students, get 12 responses, do five t‑tests, and claim that P = 0.07 means “trending toward significance.”

Avoid this by:

- Planning sample size with a power calculation (simple tools and faculty help are enough)

- Limiting outcomes to a few primary endpoints

- Reporting effect sizes and CIs, and being honest about exploratory nature

3. Vague or Home‑Made, Unvalidated Instruments

You create a “burnout scale” with three questions you wrote on your phone.

Instead:

- Search for validated instruments in MedEd or psychology literature.

- If adapting, clearly document changes and reasons.

- Pilot test your survey or checklist for clarity and reliability.

4. Confusing Program Evaluation with Research

Program evaluation serves local decision‑making: did the new anatomy schedule work for our students?

Research aims at generalizable knowledge.

They overlap, but:

- For research, you need clear research questions, theory, and often IRB review.

- For evaluation only, your work might not be publishable as “research” but could still form the basis of a later, more rigorous study.

Label your work accurately. Some journals do accept well‑designed program evaluations as MedEd scholarship.

Practical Steps to Launch a Strong MedEd Project as a Student

To translate all of this into action, here is a concrete roadmap.

Step 1: Clarify Your Question Using Frameworks

Define:

- Is this descriptive, comparative, or exploratory (how/why)?

- Which Kirkpatrick level am I targeting?

- Where on Miller’s Pyramid does my intervention operate?

If you cannot answer those, pause and refine the idea.

Step 2: Choose an Outcome Portfolio, Not Just One Score

Aim for 2–3 complementary outcome types, for example:

- Knowledge / application (MCQs, SAQs)

- Affective or cognitive (self‑efficacy, cognitive load, mindset)

- Behavioral or performance (OSCE scores, actual practice behaviors)

- Qualitative themes (learner experiences, barriers, facilitators)

This gives your study more depth and protects against over‑interpreting a single metric.

Step 3: Match Design to Feasibility

Constrain by:

- Time (how long until you graduate?)

- Access (who controls exam data, OSCE scores, or EHR?)

- Sample size (size of your class, realistic participation rate)

Then select from:

- Cross‑sectional survey

- One‑group pre/post with retention

- Quasi‑experimental comparison groups

- Qualitative interviews/focus groups

- Mixed‑methods sequence

Step 4: Secure a Methodologically Savvy Mentor

Content expertise (e.g., anatomy, pharmacology) is not enough.

You want at least one mentor who:

- Has published MedEd research (not just clinical research)

- Understands qualitative or mixed‑methods if you are using them

- Has navigated your institution’s IRB and assessment systems

Ask them explicitly to critique your design choices, not just your idea.

Step 5: Build Quality into the Protocol

Before IRB submission:

- Specify primary and secondary outcomes

- Define inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Plan the analysis in outline form:

- What comparisons?

- What effect sizes?

- What thematic analysis approach if qualitative?

Document this in a short protocol. It will save you from post‑hoc fishing expeditions and will impress mentors and reviewers.

FAQs

1. Can a purely qualitative MedEd project be enough for residency applications, or do I need “hard numbers”?

Yes, a well‑designed qualitative project can be just as impressive, sometimes more so. Program directors who value education recognize that understanding how and why learners change requires methods beyond numbers. A rigorous qualitative study with clear research questions, transparent analytic methods, and meaningful implications will often be viewed more favorably than a weak pre/post MCQ study with small sample size and superficial analysis. The key is rigor: clear sampling strategy, systematic coding, and coherent linkage to existing literature.

2. How large does my sample size need to be for a student MedEd project?

There is no single threshold. For straightforward pre/post MCQ studies, you generally want at least 30–50 participants to have reasonable power to detect medium effect sizes, assuming typical test variability. For cross‑sectional surveys, higher response rate matters more than raw N; a 70% response from 100 eligible students is stronger than 20% from 500. For qualitative work, sample sizes of 12–25 individual interviews or 3–6 focus groups can be entirely appropriate if you reach thematic saturation and analyze the data rigorously.

3. How do I handle the fact that I am studying my own classmates or peers?

This is a common and manageable issue. You must: (a) ensure voluntary participation with no coercion; (b) de‑identify data so that you cannot link responses to names when analyzing; and (c) avoid any role where you directly influence grades or evaluations. Often, an administrative office or faculty member will handle recruitment and initial data linkage, then strip identifiers before you see the dataset. Your IRB application should address these power dynamics explicitly.

4. Are there particular journals that are more open to student‑led MedEd research?

Major journals like Academic Medicine, Medical Education, Advances in Health Sciences Education, and Medical Teacher do publish student‑authored work, but competition is intense. More accessible venues include BMC Medical Education, Advances in Medical Education and Practice, The Clinical Teacher, and regional or specialty‑specific education journals (e.g., Journal of Surgical Education). Regardless of target, reviewers primarily evaluate methodological rigor and clarity of contribution, not the seniority of the first author.

Key takeaways:

- Design your MedEd study around clear frameworks (Kirkpatrick, Miller) and choose outcomes that extend beyond short‑term multiple‑choice gains.

- Leverage designs that are feasible for students yet methodologically sound: strengthened pre/post, cross‑sectional, qualitative, or mixed‑methods.

- A focused, rigorous project with thoughtful outcomes and clear design will carry far more weight—for journals and for residency applications—than yet another “MCQ scores went up” study.