Most weak medical abstracts fail not because the science is bad, but because the structure is sloppy.

If you are premed or in medical school, learning to build a tight, line‑by‑line abstract is one of the highest‑yield research skills you can acquire. Journals, conferences, admissions committees, and selection panels will judge your work in 250 words or less. That means structure is not a formality; it is your survival mechanism.

Let me break this down, section by section, sentence by sentence, with concrete examples and word‑count targets you can actually use.

The Blueprint: What a Strong Medical Abstract Must Do

Before we go line‑by‑line, anchor on this: a medical abstract is not a mini‑paper. It is a highly compressed sales pitch for:

- The problem (why anyone in medicine should care)

- The method (that you did something legitimate)

- The results (that something actually happened)

- The implications (why it matters beyond your dataset)

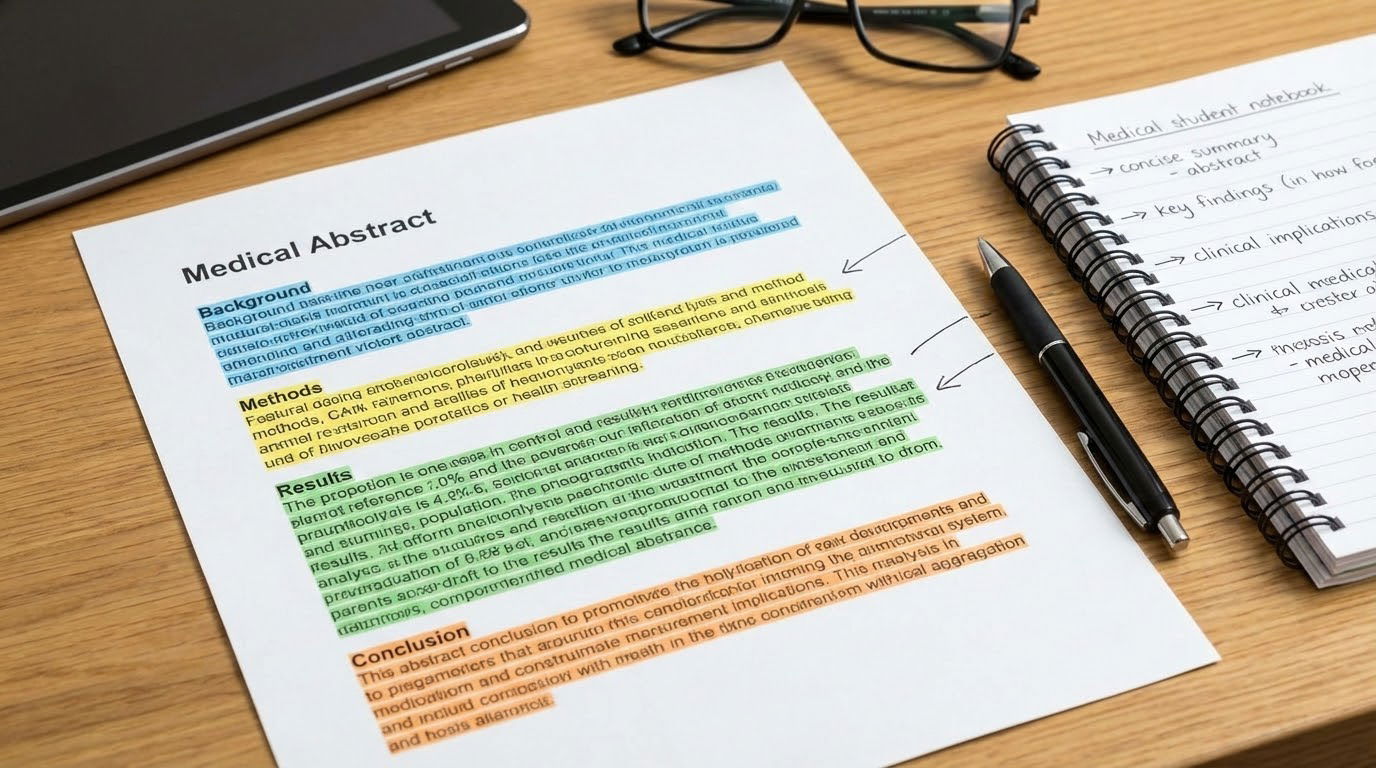

For structured abstracts in medicine, you will almost always see these sections:

- Background (or Introduction)

- Methods

- Results

- Conclusion (or Conclusions)

Some journals add Objectives, Setting, or Limitations. But as a student, if you master these four, you can adapt to almost any template within minutes.

For each section, I will give you:

- Purpose of the section

- Line‑by‑line roles

- Word count range (for a typical 250–300 word abstract)

- A concrete example from a plausible student‑level research project

Target total: 250 words is common for conferences; 250–300 words for many journals. Always check the instructions, but use 250 as your default training constraint. Writing shorter forces clarity.

Background: Sharpening the Why in 2–3 Sentences

The Background is where most students waste words. They write a mini‑review of the literature instead of a surgical justification for their study.

Your mission in the Background: move the reader from “general field” → “specific gap” → “your objective” in 2–3 sentences. Not four. Not seven.

Target word count: 40–70 words.

Target length: 2–3 sentences.

Line‑by‑Line Structure for Background

Sentence 1 – Clinical or public health importance.

State the broader problem, but be specific, not vague.

Bad:

“Hypertension is a common medical condition.”

Better:

“Hypertension is a leading modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality worldwide.”

You are signaling: this is a real problem clinicians care about.

Sentence 2 – The gap in knowledge/practice.

Shift from “this is important” to “something we do not yet know or do poorly”.

Bad:

“However, not much is known about hypertension in young adults.”

Better:

“However, data on blood pressure screening practices among young adults in primary care settings remain limited.”

Now you are narrowing to your project’s niche.

Sentence 3 – The specific aim / objective.

This is not optional. If the journal does not require a separate Objectives section, end your Background with a clear, single‑sentence objective. Use one of these stems:

- “We aimed to…”

- “This study evaluated…”

- “Our objective was to…”

Example:

“We aimed to assess blood pressure screening rates and associated factors among patients aged 18–35 in an urban academic primary care clinic.”

That closes the loop: important problem → specific gap → what you did.

Complete Background Example (60 words)

Hypertension is a leading modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality worldwide. However, data on blood pressure screening practices among young adults in primary care settings remain limited. We aimed to assess screening rates and associated factors among patients aged 18–35 years in an urban academic primary care clinic.

Three sentences, 60 words. Clean, specific, and it naturally opens the door for your Methods.

Methods: Showing That Your Study Is Real and Reproducible

The Methods section is where abstract rookies either under‑specify (“We did a study”) or over‑specify (full inclusion criteria, every statistical test). You need enough detail to prove rigor, but not enough to rewrite your methods section.

Target word count: 60–90 words.

Target length: 3–5 sentences.

The Non‑Negotiable Components

Include, in some form:

- Study design (retrospective cohort, randomized trial, cross‑sectional survey, qualitative interviews, etc.)

- Setting and population (where, when, and who)

- Key variables / outcomes (what you measured)

- Analysis approach (basic statistical or qualitative method)

Line‑by‑Line Structure for Methods

Sentence 1 – Design and setting.

Example:

“We conducted a cross‑sectional study at an urban academic internal medicine clinic from January 2022 to December 2022.”

Design (“cross‑sectional”) + setting (“urban academic internal medicine clinic”) + timeframe.

If it is a trial or multi‑center study:

“We performed a randomized, controlled trial across three tertiary‑care hospitals in the Midwest between 2020 and 2023.”

Sentence 2 – Participants and inclusion criteria.

Concise but specific.

Example:

“Adult patients aged 18–35 years with at least one clinic visit during the study period were eligible.”

If you have key exclusions:

“…Patients with documented pregnancy or end‑stage renal disease were excluded.”

Do not list every exclusion unless unusual or critical.

Sentence 3 – Variables and primary outcome.

Clarify what you measured, and what your primary outcome was.

Example:

“We extracted demographic data, comorbidities, and all recorded blood pressure measurements from the electronic medical record; the primary outcome was documentation of at least one blood pressure measurement during an eligible visit.”

You are telling the reader: these are not vague “factors”; they are defined.

Sentence 4 – Analytic methods.

One sentence is usually enough.

Example:

“We used multivariable logistic regression to identify factors associated with blood pressure screening, adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and comorbidities.”

If the study is simple (descriptive only), that is fine:

“Data were summarized using descriptive statistics.”

For qualitative work:

“Interviews were transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis with double‑coding by two independent reviewers.”

Optional Sentence 5 – Ethical approval (if requested).

Some conferences or journals expect a brief ethics statement, especially for clinical or human subjects work.

Example:

“The institutional review board approved the study with a waiver of informed consent.”

Complete Methods Example (87 words)

We conducted a cross‑sectional study at an urban academic internal medicine clinic from January 2022 to December 2022. Adult patients aged 18–35 years with at least one clinic visit during the study period were eligible; patients with documented pregnancy or end‑stage renal disease were excluded. We extracted demographic variables, comorbidities, and all recorded blood pressure measurements from the electronic medical record. The primary outcome was documentation of at least one blood pressure measurement per visit. We used multivariable logistic regression to identify factors associated with screening.

You can trim this down as needed to hit your word limit, but this level of specificity signals credibility.

Results: The Engine Room of Your Abstract

If the Background and Methods are competent but your Results are vague, your abstract dies. Admission committees reading conference abstracts, research elective applications, or posters will look for one thing above all: did this project actually produce clear, quantitative findings?

Your task in the Results is to:

- Report numbers, not feelings

- Prioritize the primary outcome

- Include key effect sizes with p‑values or confidence intervals where relevant

- Avoid over‑explaining or interpreting (that belongs in the Conclusion)

Target word count: 80–110 words.

Target length: 3–5 sentences.

Line‑by‑Line Structure for Results

Sentence 1 – Sample description and size.

You must state your sample size and the core characteristics.

Example:

“Of 1,245 eligible patients, 1,032 (82.9%) had at least one documented clinic visit with complete data.”

You can briefly characterize the population in the same or next sentence:

“The mean age was 27.4±4.8 years; 58% were female and 45% identified as Black.”

If you are heavily constrained by word limits, keep it to sample size and one or two key descriptors.

Sentence 2 – Primary outcome.

Go straight to your main result. Include numbers and percentages.

Example:

“Overall, blood pressure was recorded in 78.5% of visits (2,853/3,635).”

No commentary, no interpretation, just the core finding.

Sentence 3 – Key comparative or association results.

This is where you report what your main analysis found. Effect sizes plus either p‑values or confidence intervals.

Example:

“In adjusted analyses, patients with obesity were more likely to have blood pressure measured (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.42, 95% CI 1.10–1.84), whereas younger age (18–24 years) was associated with lower screening rates (aOR 0.71, 95% CI 0.55–0.93).”

Notice: no “trend toward significance,” no speculation. Just data.

Sentence 4 – Secondary finding or subgroup, if truly important.

Only include if it reinforces your main story.

Example:

“Screening rates varied significantly by provider type, ranging from 69.2% among resident physicians to 85.7% among attending physicians (p<0.001).”

If you are pressed for space, drop secondary outcomes first.

Sentence 5 – One sentence for unexpected or safety findings (trials).

For clinical trials or interventions, you might add:

“No serious adverse events related to the intervention were observed.”

For many student projects, this can be omitted.

Complete Results Example (105 words)

Of 1,245 eligible patients, 1,032 (82.9%) had at least one documented clinic visit with complete data during the study period. The mean age was 27.4±4.8 years; 58% were female and 45% identified as Black. Overall, blood pressure was recorded in 78.5% of visits (2,853/3,635). In adjusted analyses, patients with obesity were more likely to have blood pressure measured (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.42, 95% CI 1.10–1.84), whereas age 18–24 years was associated with lower screening rates (aOR 0.71, 95% CI 0.55–0.93). Screening rates varied significantly by provider type, ranging from 69.2% among residents to 85.7% among attendings (p<0.001).

Every sentence earns its place. Numbers dominate. Interpretation is left for the Conclusion.

Conclusion: From Numbers to Meaning in 2–3 Sentences

Weak abstracts collapse here. Authors re‑state their results, or worse, make grand claims not supported by the data. Your Conclusion must do three things in 2–3 sentences:

- Directly answer your study objective

- Interpret the main result in clinical or educational context

- (Ideally) point toward a next step, improvement, or implication

Target word count: 40–70 words.

Target length: 2–3 sentences.

Line‑by‑Line Structure for Conclusion

Sentence 1 – Direct answer to the objective.

You are not repeating the Methods; you are summarizing what you found, conceptually.

Objective (from Background):

“We aimed to assess screening rates and associated factors…”

Conclusion, sentence 1:

“Blood pressure screening among young adults in this primary care clinic was suboptimal, particularly for patients aged 18–24 years and visits with resident physicians.”

Notice: no exact percentages, but clear, high‑level pattern.

If your main finding is positive:

“The intervention significantly improved hand hygiene compliance among medical students during inpatient rotations.”

Tie this directly to your stated objective.

Sentence 2 – Clinical or educational implication.

Move beyond description to meaning. Be specific but modest.

Example:

“These findings highlight the need for targeted quality‑improvement efforts focusing on younger patients and trainee providers to ensure early detection of hypertension.”

You are not implementing a national policy. You are situating your data within a realistic action step.

Sentence 3 – Future directions or next step (optional, if space allows).

This is where you can hint at what should happen next, within reason.

Example:

“Future work should evaluate whether standardized clinic protocols or electronic health record prompts can reduce missed screening opportunities in this population.”

If you are forced to cut, remove the third sentence first.

Complete Conclusion Example (56 words)

Blood pressure screening among young adults in this academic primary care clinic was suboptimal, particularly for patients aged 18–24 years and visits with resident physicians. These findings highlight the need for targeted quality‑improvement initiatives focusing on younger patients and trainee providers to ensure early detection of hypertension. Future work should test system‑level interventions to standardize screening.

This answers the “So what?” without overpromising.

Putting It All Together: A Full Structured Abstract

Now assemble the pieces into a coherent, line‑by‑line structured abstract typical of medical conferences or journals. Total word count: roughly 250–280 words.

Background: Hypertension is a leading modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality worldwide. However, data on blood pressure screening practices among young adults in primary care settings remain limited. We aimed to assess screening rates and associated factors among patients aged 18–35 years in an urban academic internal medicine clinic.

Methods: We conducted a cross‑sectional study at an urban academic internal medicine clinic from January 2022 to December 2022. Adult patients aged 18–35 years with at least one clinic visit during the study period were eligible; patients with documented pregnancy or end‑stage renal disease were excluded. We extracted demographic variables, comorbidities, and all recorded blood pressure measurements from the electronic medical record. The primary outcome was documentation of at least one blood pressure measurement per visit. We used multivariable logistic regression to identify factors associated with screening.

Results: Of 1,245 eligible patients, 1,032 (82.9%) had at least one documented clinic visit with complete data during the study period. The mean age was 27.4±4.8 years; 58% were female and 45% identified as Black. Overall, blood pressure was recorded in 78.5% of visits (2,853/3,635). In adjusted analyses, patients with obesity were more likely to have blood pressure measured (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.42, 95% CI 1.10–1.84), whereas age 18–24 years was associated with lower screening rates (aOR 0.71, 95% CI 0.55–0.93). Screening rates varied significantly by provider type, ranging from 69.2% among residents to 85.7% among attendings (p<0.001).

Conclusion: Blood pressure screening among young adults in this academic primary care clinic was suboptimal, particularly for patients aged 18–24 years and visits with resident physicians. These findings highlight the need for targeted quality‑improvement initiatives focusing on younger patients and trainee providers to ensure early detection of hypertension. Future work should test system‑level interventions to standardize screening.

You can feel how each section does a specific job. There is no filler. The background sets up the question, the methods prove the study is real, the results deliver numbers, and the conclusion explains why those numbers matter.

Line‑By‑Line Editing: How to Tighten a Student Abstract

Knowing the ideal structure is one thing; getting your own messy draft to look like that is another. The fastest way to improve is to edit line‑by‑line with a clear checklist.

Work through each section with these questions.

Background Editing Checklist

For each sentence:

Sentence 1:

- Does it state a specific clinical or public health problem?

- Can any clause be cut without losing meaning?

Sentence 2:

- Does it identify a real gap (knowledge, practice, population, method)?

- Is it too broad (“little is known”) without specifying what exactly is unknown?

Sentence 3 (Objective):

- Is there a clear action verb? (assess, evaluate, compare, determine, develop)

- Does it mention the population, setting, and main outcome/exposure?

If you have more than three Background sentences, cut until you reach three. Forced concision will improve your writing.

Methods Editing Checklist

- Underline your study design. If you cannot find it, add it in the first sentence.

- Circle the population descriptors. Do they include age range and setting?

- Highlight your primary outcome. If the reader cannot tell what you defined as primary, you have a problem.

- Look for jargon (“we conducted advanced multivariate analyses…”). Replace with neutral, specific language (“we used Cox proportional hazards models…”).

Trim phrases like “in order to,” “the aim of this study was to,” and “it was determined that.” They almost never add value.

Results Editing Checklist

This is where applicants to medical school research tracks are often judged.

- Count your numbers. You should have several: sample size, key percentages, odds ratios or other effect sizes. If you have only words (“higher”, “lower”, “more likely”), add concrete numbers.

- Remove statistical methods from Results. They belong in Methods.

- Check that your first Results sentence gives the sample size. If not, fix that.

- Avoid redundant phrases: “The results of this study showed that…” Simply state the result.

Conclusion Editing Checklist

- Compare your Conclusion to your Objective. Are they directly connected?

- Make sure you are not introducing new results that never appeared in the Results section.

- Soften speculative language. Replace “will improve” with “may improve” or “could improve” unless you have very strong causal evidence (rare for student projects).

- Check for over‑claiming: if your study is single‑center, do not claim global generalizability.

Adapting to Different Abstract Formats (Premed and Med Student Contexts)

Premed and early medical students will encounter several abstract formats:

- Undergraduate research symposia: Often 250–300 words, unstructured or lightly structured.

- Specialty‑specific conferences (e.g., ACP, AMSA, AAMC): Usually structured with Background, Methods, Results, Conclusion.

- Q‑I and education conferences: Sometimes use “Problem,” “Intervention,” “Measures,” “Results,” “Conclusions.”

The underlying logic stays the same; you just rename the boxes.

Example: Quality Improvement Abstract

Standard clinical abstract → QI template:

- Background → Problem

- Methods → Intervention / Methods

- Results → Measures / Results

- Conclusion → Conclusions / Lessons learned

So if your project was “Reducing unnecessary telemetry orders on a general medicine ward,” your Background sentence “Telemetry is frequently overused…” becomes the Problem. Your Methods sentence describing a new order set becomes Intervention. The structure and line‑by‑line logic remain identical.

Example: Medical Education Abstract

For education research (OSCE performance, flipped classroom, etc.), your “outcome” is likely knowledge scores or learner satisfaction. The same line‑by‑line pattern applies:

- Background: education problem + gap in teaching methods

- Methods: learners, curriculum, assessment tools, analysis

- Results: scores, ratings, effect sizes

- Conclusion: implications for teaching practice and curriculum design

Once you internalize the pattern, the content can vary wildly—clinical, basic science, education, QI—without changing your approach.

How to Practice: Turning a Full Paper into an Abstract

If you are early in your training, the fastest way to master structured abstracts is to reverse‑engineer published ones.

Pick a paper from a clinical journal (JAMA Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, Academic Medicine) and do this exercise:

Cover the abstract.

Read only the full paper’s Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion.Write your own 250‑word abstract using the line‑by‑line structure we covered:

- 3 sentences for Background + Objective

- 4 sentences for Methods

- 4 sentences for Results

- 3 sentences for Conclusion

Uncover the published abstract and compare:

- How close are your Background sentences to theirs?

- Did you pick the same primary outcome?

- Are your numbers in the Results similar in emphasis?

Do this five times and your abstract instincts will sharpen dramatically.

Three Things to Remember

- Strong abstracts are built, not discovered. A clear line‑by‑line template for Background, Methods, Results, and Conclusion will keep your writing disciplined and your science visible.

- Numbers and specificity win. Wherever possible, replace vague phrases with concrete data, defined outcomes, explicit designs, and clear objectives.

- Every sentence must earn its space. At 250 words, you are not decorating; you are triaging. If a sentence does not serve the problem, the method, the key results, or the implication, cut it.