Understanding H‑1B Sponsorship in Vascular Surgery Residency

For international medical graduates (IMGs) hoping to train in the United States, vascular surgery is one of the most competitive and specialized surgical fields. Layered on top of that challenge is the complexity of U.S. immigration law. If you are not a U.S. citizen or permanent resident, you will likely need either a J‑1 or an H‑1B visa to train.

This guide focuses on H‑1B sponsorship programs in vascular surgery, explaining how they work, where to find them, and how to build a strategy that maximizes your chances of matching.

We will look at:

- How vascular surgery training is structured in the U.S.

- Key differences between J‑1 and H‑1B for residency

- How H‑1B works in the integrated vascular program and the independent fellowship pathway

- How to identify H‑1B residency programs, interpret institutional policies, and use an H‑1B sponsor list

- Application strategies tailored for IMGs targeting H‑1B‑friendly vascular surgery programs

Throughout, remember: visa policies change frequently. Always verify details directly with programs and your legal counsel before making decisions.

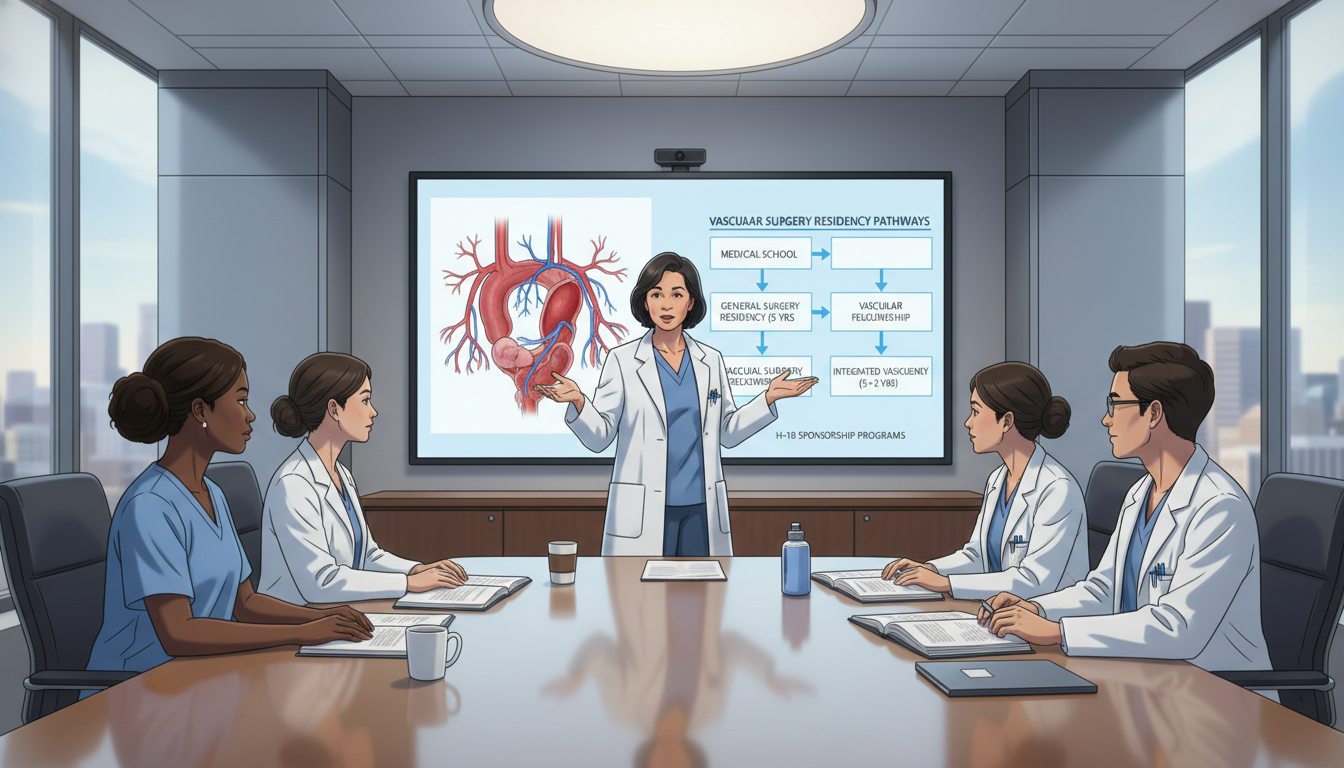

1. Vascular Surgery Training Pathways and Visa Basics

To understand H‑1B sponsorship in vascular surgery, you first need to know how vascular training is structured and which phases may require which type of visa.

1.1 Vascular Surgery Training Pathways

There are two primary routes to become a vascular surgeon in the U.S.:

Integrated Vascular Surgery Residency (0+5)

- Apply directly from medical school (or after preliminary training) to a vascular surgery residency that lasts 5 years.

- Combines core surgery training with progressive vascular responsibilities from the outset.

- Competitive, small number of positions; many programs in major academic centers.

- Visa sponsorship usually applies from PGY‑1 through PGY‑5.

Independent Vascular Surgery Fellowship (5+2)

- Complete a 5‑year general surgery residency first.

- Then apply for a 2‑year vascular surgery fellowship.

- Visa consideration applies twice: once at the general surgery level, and again for vascular fellowship.

For IMGs pursuing H‑1B, the integrated pathway compresses decisions and immigration planning into a single match. The independent pathway introduces additional visa transitions and timing concerns.

1.2 J‑1 vs H‑1B: What’s the Difference for Training?

Most residency and fellowship programs sponsor J‑1 visas through the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG). Fewer sponsor H‑1B. Understanding the trade‑offs is crucial.

J‑1 Visa (ECFMG‑Sponsored):

- Common, relatively streamlined for training.

- Typically limited to the duration of the ACGME‑accredited training.

- Almost always associated with the two‑year home‑country physical presence requirement after completion (unless you obtain a waiver).

- Changing specialties or adding non‑ACGME fellowships can be more complex.

H‑1B Visa (Employer‑Sponsored):

- Sponsored by the hospital or university (the residency/fellowship employer).

- Dual intent: compatible with long‑term immigration planning and green card pathways.

- No automatic 2‑year home-return requirement like J‑1.

- Requires passing USMLE Step 3 before issuance (in almost all residency contexts).

- Comes with wage, prevailing salary, and regulatory compliance requirements, so some institutions avoid it.

- Residency/fellowship positions in teaching hospitals are generally H‑1B cap exempt, which is critical (more on this below).

For many IMGs, an H‑1B is appealing because it avoids the J‑1 waiver process and can align more easily with later employment. However, the limited number of H‑1B residency programs and added administrative burdens mean that not every vascular surgery program will offer it.

2. How H‑1B Works for Vascular Surgery Residency and Fellowship

2.1 H‑1B Cap Exempt vs Cap Subject

The single most important legal distinction for residency/fellowship H‑1Bs is whether the position is H‑1B cap exempt.

Cap‑Exempt:

- Not counted against the annual national H‑1B quota (the “cap”).

- Exempt if the employer is a:

- Nonprofit hospital affiliated with an institution of higher education

- University/medical school

- Certain nonprofit research organizations

- Most large academic medical centers (where vascular surgery programs are based) fall into this category.

- You can start any time of year, not just October 1, once approved.

Cap‑Subject:

- Counted toward the nationwide numerical limit.

- Requires entry via the H‑1B lottery (highly competitive and uncertain).

- Much less common for residency/fellowship; may apply if training is in a community hospital without an academic affiliation.

Most integrated vascular programs and vascular fellowships attached to university medical centers will be H‑1B cap exempt, which is a major advantage: no lottery, more predictable start dates, and easier internal transitions.

2.2 H‑1B for the Integrated Vascular Program (0+5)

When you apply to a 0+5 integrated vascular surgery residency, each program’s stance on H‑1B can vary:

- Some sponsor J‑1 only

- Some sponsor J‑1 and H‑1B (often with conditions)

- A few may not sponsor any visas (rare in major academic centers, but does occur)

If a program sponsors H‑1B, they must:

- Demonstrate that your training role qualifies as a specialty occupation.

- Show that they will pay at least the prevailing wage for your training level.

- File a Labor Condition Application (LCA) and H‑1B petition to USCIS.

- Ensure you have USMLE Step 3 passed by their stated deadline (commonly before starting PGY‑1, sometimes by a pre‑match date).

Complications in the integrated pathway:

- The longer duration (5 years) may require careful planning of H‑1B extensions (usually initially granted up to 3 years; can be extended to a maximum of 6 years in most cases).

- Some institutions prefer J‑1 for long training because it is administratively simpler across multiple years.

- H‑1B portability (changing employers) is possible, but mid‑residency transfers are complex and may jeopardize training continuity.

In practice, integrated vascular programs that sponsor H‑1B often have standardized policies shared across all their GME programs.

2.3 H‑1B for Vascular Surgery Fellowship (5+2)

For the independent vascular surgery fellowship, H‑1B issues depend on:

- The visa you used in general surgery residency

- The new institution’s sponsorship policies

Common scenarios:

You trained in general surgery on J‑1

- For fellowship, many vascular programs will expect continued J‑1 sponsorship.

- Switching from J‑1 to H‑1B for fellowship is possible, but you must consider the two‑year home rule and waiver options.

You trained in general surgery on H‑1B

- You may extend H‑1B under a cap‑exempt arrangement for fellowship at a qualifying academic center.

- Coordination between your current program’s legal office and the fellowship institution is essential to avoid any gap in status.

Some vascular fellowships that are attached to departments already familiar with H‑1B may be more open to sponsorship. Others—especially smaller programs—might default to J‑1 only because that is what their GME and legal offices understand best.

3. Identifying H‑1B‑Friendly Vascular Surgery Programs

Because official lists are incomplete and policies change frequently, identifying vascular surgery H‑1B sponsors requires a structured approach.

3.1 Using Official and Semi‑Official Sources

Program Websites (Integrated and Fellowship)

- Check the GME (Graduate Medical Education) section first; many institutions post a general statement:

- “We sponsor J‑1 and H‑1B visas for eligible trainees”

- “We sponsor J‑1 only”

- “We do not sponsor H‑1B for residency programs”

- Then cross‑check on the vascular surgery residency or fellowship page for any specialty‑specific notes.

- Remember: absence of a statement ≠ no sponsorship. It simply means you must ask.

- Check the GME (Graduate Medical Education) section first; many institutions post a general statement:

FRIEDA and ACGME / Program Directories

- FRIEDA (AMA) and similar databases sometimes mention visa types accepted (J‑1, H‑1B, or both).

- These entries can be outdated; use them as a starting point, not final authority.

Institution‑Level H‑1B Sponsor List

- Many universities and health systems maintain a public or semi‑public H‑1B sponsor list showing the job categories (including residents/fellows) for which they have historically filed petitions.

- They may not break it down by specialty, but if the GME office appears on such a list, this suggests a track record of cap‑exempt sponsorship.

- If the institution is a major medical school or large teaching hospital, it is very likely cap‑exempt.

ECFMG / NRMP Guidance

- ECFMG offers general guidance on J‑1 vs H‑1B, and NRMP career resources sometimes highlight institutions that consistently match IMGs on H‑1B.

- Use this to generate a core target list of “IMG‑friendly” academic centers in surgery and subspecialties.

3.2 Direct Communication: What and How to Ask

Because vascular surgery is small and policies can vary even within the same hospital, emailing the right people is essential.

Who to contact:

- Program Coordinator (first line of contact)

- Program Director (if needed)

- GME Office or Institutional Visa/Immigration Office (for policy clarification)

What to ask (concisely and professionally):

- Confirm sponsorship:

- “Does your integrated vascular surgery residency sponsor H‑1B visas, J‑1 visas, or both for international medical graduates?”

- Clarify conditions:

- “If you sponsor H‑1B, are there any additional requirements (e.g., USMLE Step 3 by a specific date, prior U.S. clinical experience)?”

- Ask about recent practice:

- “Have you sponsored H‑1B visas for residents or fellows in surgical specialties in recent years?”

Avoid long autobiographical emails initially. Focus on direct questions that help you decide whether to apply.

3.3 Recognizing Red Flags and Grey Areas

Some responses require careful interpretation:

- “We have sponsored H‑1B in the past, but prefer J‑1”

- This may mean they will consider H‑1B only in exceptional circumstances (e.g., outstanding candidate, specific institutional need).

- “We sponsor H‑1B for fellows, but not for residents”

- Integrated vascular programs may be more restrictive than fellowships.

- “We can’t comment until after interview”

- Some programs truly evaluate on merit first, but you must decide whether to invest time and money in the interview with visa uncertainty.

Keep a personal spreadsheet tracking:

- Program name

- Pathway (0+5; 5+2 fellowship)

- Visa policy (J‑1 only; J‑1 + H‑1B; unclear)

- Who you spoke with and when

- Any special notes (e.g., Step 3 deadline, preference order, previous IMG H‑1B success)

Over time, this becomes your personalized H‑1B sponsor list for vascular surgery.

4. Application Strategy for IMGs Targeting H‑1B in Vascular Surgery

In a small, competitive field like vascular surgery, you must optimize both your overall strength as an applicant and your visa positioning.

4.1 Core Competitiveness in Vascular Surgery

Even before visa considerations, vascular surgery expects:

- Strong USMLE/COMLEX scores (especially important if you’re competing for limited H‑1B‑friendly spots).

- Robust surgical clerkship and sub‑internship (sub‑I) performance.

- Demonstrated interest in vascular:

- Electives with vascular surgery teams

- Research in vascular biology, endovascular technology, outcomes, or health services

- Presentations at meetings (SVS, local or regional vascular conferences)

- Excellent letters of recommendation from vascular surgeons or general surgeons strongly familiar with your work.

- Teamwork, communication skills, and professionalism—critical in close‑knit vascular teams.

Visa considerations are secondary to this foundation; you need to be someone the program genuinely wants, independent of sponsorship.

4.2 USMLE Step 3: The H‑1B Gatekeeper

For H‑1B residency programs, Step 3 is often mandatory before they can file your petition. Concrete steps:

- Plan to pass USMLE Step 3 before Rank Order List deadlines or by the date stated by programs (often by early spring before July start).

- If you are still in medical school outside the U.S., this will be logistically challenging; you may need:

- ECFMG certification early

- Time in the U.S. for Prometric testing

- If you are already in a prelim or transitional year in the U.S., prioritize Step 3 early in PGY‑1.

Without Step 3, some programs cannot or will not file H‑1B, regardless of how strong your application is.

4.3 Building a Target List: Balancing Ambition and Reality

Strategy for constructing your list:

Anchor Institutions

- Identify 5–10 academic centers known to be:

- Strong in vascular surgery

- Consistent with IMG recruitment in surgery

- Historically open to H‑1B (via your research)

- These are your high‑priority targets.

- Identify 5–10 academic centers known to be:

Mix of Pathways

- Apply to:

- Integrated vascular surgery programs (0+5) that support H‑1B.

- General surgery programs that sponsor H‑1B (if you are open to the 5+2 pathway).

- This increases your odds of entering a surgical track with vascular opportunities later.

- Apply to:

Geographic Flexibility

- Being open to a wide geographic range dramatically increases the pool of potential H‑1B residency programs.

- Don’t limit yourself to a few major coastal cities.

Backup Plans

- Include J‑1‑friendly programs if you are open to that route; you can still pursue long‑term U.S. engagement via a J‑1 waiver job after training.

- Consider preliminary surgery spots with H‑1B sponsorship as a stepping stone while you strengthen your application and complete Step 3.

4.4 Communicating Your Visa Needs Without Undermining Your Application

When to mention H‑1B:

- ERAS Application:

- Be honest about your current status (e.g., “Requires visa sponsorship”).

- You usually don’t have to specify H‑1B vs J‑1 in the application itself.

- Before or After Interview Invitations:

- Once invited, it is appropriate to clarify visa possibilities if not already clearly stated.

- Frame your question neutrally: “Could you please confirm which visa types your program can sponsor for international graduates?”

During the interview:

- If asked directly about visa status, answer clearly and confidently.

- Emphasize:

- You have already passed or scheduled Step 3 (if true).

- You understand and respect institutional policies and will follow their process.

- Do not let visa concerns dominate your narrative. Focus on your fit with vascular surgery, your clinical and academic potential, and your professional goals.

5. Long‑Term Career and Immigration Planning for Vascular Surgeons

Choosing between J‑1 and H‑1B is not just about residency; it affects your entire career trajectory as a vascular surgeon.

5.1 Post‑Training Employment Landscape in Vascular Surgery

Vascular surgery is in demand across the U.S., including:

- Large academic centers

- Regional referral hospitals

- Community hospitals with endovascular capability

- Integrated health systems (e.g., large non‑profit networks)

For IMGs:

- Many employers are familiar with recruiting foreign‑trained vascular surgeons.

- H‑1B (cap‑subject this time, unless the new employer is also cap‑exempt) and employment‑based green card sponsorship are common routes.

5.2 Advantages of H‑1B Training for Future Employment

If you complete vascular training on H‑1B:

- You may transition directly into H‑1B employment with a new employer (portability).

- You do not face the J‑1 two‑year home country requirement or need for a J‑1 waiver job.

- You can pursue permanent residency (green card) through EB‑2 or EB‑1 categories, depending on your accomplishments and employer support.

However, after training, you may be moving from a cap‑exempt training position to a cap‑subject job unless your new employer is another academic or qualifying non‑profit. That may mean entering the lottery at some point, depending on timing and alternative pathways.

5.3 If You Train on J‑1 but Still Want Long‑Term U.S. Practice

Many IMGs in vascular surgery ultimately train on J‑1 despite initial hopes for H‑1B. You still have options:

J‑1 Waiver Positions:

- Many underserved or rural hospitals need vascular or endovascular surgeons.

- Programs such as Conrad 30 waivers are more common in primary care, but waivers for specialists, including vascular surgery, do exist in certain states and institutions.

Academic Pathways:

- Some academic centers can support J‑1 waiver requests if there is a documented need and they meet specific criteria.

Even if you initially focus on H‑1B‑friendly vascular programs, it is prudent to understand J‑1 waiver possibilities as a backup.

6. Practical Checklist and Action Plan for IMGs

To turn all of this into a workable plan, use this condensed roadmap.

6.1 18–24 Months Before Match (or Fellowship Start)

- Confirm your eligibility:

- ECFMG certification timeline

- Exam status (Step 1, Step 2 CK; plan Step 3).

- Begin vascular‑focused experiences:

- Clinical electives, observerships, or research with vascular teams.

- Build contacts with vascular surgeons who might later provide strong letters.

6.2 12–18 Months Before Match

Take or schedule USMLE Step 3, aiming to have it passed by the time programs need to file H‑1B paperwork.

Create a preliminary H‑1B sponsor list:

- Review vascular surgery integrated programs and vascular fellowships.

- Check institutional GME pages for visa policies.

- Note which are likely H‑1B cap exempt (most academic centers).

Reach out to a select set of program coordinators to confirm up‑to‑date sponsorship details.

6.3 9–12 Months Before Match

- Finalize your ERAS (or relevant fellowship application platform):

- Highlight vascular interest (research, electives, case logs).

- Mention ongoing or completed Step 3 in your CV and personal statement if appropriate.

- Apply broadly:

- H‑1B‑friendly integrated vascular programs.

- H‑1B general surgery programs (if considering 5+2 pathway).

- Additional J‑1‑friendly programs, depending on your risk tolerance.

6.4 Interview Season

Keep a running log of conversations about visa sponsorship with each program.

Clarify:

- Visa types they can sponsor.

- Any internal hierarchy (J‑1 preference vs equal standing).

- Concrete Step 3 and documentation deadlines.

During interviews:

- Focus on fit, not visa.

- Communicate professionalism, enthusiasm, and insight into vascular surgery.

6.5 Rank List and Post‑Match

When ranking, factor in both:

- Program quality and fit.

- Visa feasibility and long‑term career implications.

After match:

- Work proactively with your program and its legal office on the H‑1B process.

- Provide requested documentation quickly (diplomas, ECFMG certificate, exam scores, CV, passport scans).

- Understand your responsibilities related to maintaining status (e.g., travel, moonlighting restrictions, work location changes).

FAQs: H‑1B Sponsorship in Vascular Surgery

1. Are there many vascular surgery residency programs that sponsor H‑1B visas?

No. Compared with J‑1, the number of vascular surgery programs open to H‑1B is limited. Most integrated vascular programs sponsor J‑1 primarily, with a subset willing to consider H‑1B, particularly at large academic centers that are H‑1B cap exempt and already familiar with sponsoring other surgical residents and fellows. You should not assume H‑1B is available; always verify with each program.

2. Do I need USMLE Step 3 for an H‑1B vascular surgery residency position?

In almost all cases, yes. The vast majority of H‑1B residency programs require Step 3 to file the H‑1B petition for a trainee. Some may allow you to interview or even rank you without Step 3, but will set a hard deadline (often early spring before the July 1 start) by which you must have passed. Without Step 3, H‑1B sponsorship for residency is rarely possible.

3. Is an H‑1B always better than a J‑1 for vascular surgery training?

Not always. H‑1B can be advantageous for long‑term immigration and avoids the J‑1 two‑year home residence requirement, but it is harder to obtain, less commonly sponsored, and may limit your choice of programs. J‑1 is more widely accepted and may open doors at excellent vascular surgery programs that do not handle H‑1B. The “better” option depends on your priorities, competitiveness, and long‑term goals.

4. Can I switch from J‑1 to H‑1B for vascular fellowship or later employment?

Yes, but with important caveats. If you train on J‑1, you are usually subject to the two‑year home‑country physical presence requirement. To switch to H‑1B for fellowship or employment in the U.S. before fulfilling those two years abroad, you typically need a J‑1 waiver (e.g., Conrad 30 or other waiver pathways). Without the waiver or completion of the two‑year requirement, you will not be eligible to change to H‑1B status within the U.S. This makes early visa strategy and legal advice essential.

This guide is meant as an educational overview. Immigration policy is complex and fact‑specific; always consult individual vascular surgery programs and a qualified immigration attorney for advice tailored to your situation.