Introduction: Saying Yes to Medicine Later in Life

Thinking about medical school in your 30s or 40s can feel both exciting and terrifying. You may already have an established career, a mortgage, children, or other major responsibilities. The idea of upending your life for a demanding medical career can trigger understandable doubts:

- Am I too old to start over?

- Will I be able to keep up academically?

- How will I support myself or my family through training?

- What if I make this leap and regret it?

These questions are common—and they don’t mean you’re not cut out for medicine. In fact, the ability to ask hard questions and realistically assess risk is one of the strengths non-traditional students bring to the profession.

Many successful physicians began their medical careers as “second-career” or “late-entry” students. Their prior experiences—from teaching and business to military service and tech—make them uniquely effective clinicians, leaders, and advocates. Medical schools increasingly recognize the value of these diverse backgrounds in improving patient care and healthcare systems.

This guide is designed to help you work through doubts and move from “Could I really do this?” to “Here’s my plan.” You’ll learn how to:

- Clarify your motivations for a medical career

- Systematically address common fears and obstacles

- See real-world examples of successful career change into medicine

- Map out concrete steps from where you are now to medical school and residency

- Build support systems so you don’t have to do it alone

If you’re a non-traditional student considering a career change into medicine, you’re not behind—you’re just on a different, equally valid timeline.

Clarifying Your “Why”: The Foundation of a Late Career Change to Medicine

When you’re considering a major life pivot, your motivations matter more than ever. Medical training is long and demanding; your “why” will anchor you when doubts inevitably show up.

Reflecting on Your Motivation for a Medical Career

Set aside time—ideally in writing—to explore:

Why do you want to practice medicine now?

Has something shifted in your life recently? A personal or family illness, burnout in your current field, or years of feeling pulled toward healthcare?What experiences have led you here?

Maybe you:- Volunteered in a clinic or hospital

- Worked in a health-adjacent role (EMT, nurse, therapist, tech professional in healthcare IT)

- Supported a loved one through a serious condition

- Realized your current career lacks the meaning or impact you crave

What do you hope a medical career will give you that your current path does not?

This might include:- Direct impact on patients and communities

- Intellectual challenge and lifelong learning

- Stability and clear advancement paths

- A sense of alignment with your values

Your answers don’t need to be perfect or poetic. They just need to be honest. This reflection will later inform your personal statement, interviews, and—more importantly—your own resilience when things get hard.

Testing Your Interest Before Committing Fully

Before committing years and significant resources, pressure-test your interest in a medical career:

- Shadow physicians in different specialties to see the real day-to-day work

- Volunteer in clinical environments (free clinics, hospitals, hospice, crisis centers)

- Take a single science course (e.g., introductory biology or chemistry) to gauge how you handle academic work again

- Talk to non-traditional physicians and students, especially those who started in their 30s or 40s

If you find yourself more energized than drained—even when it’s challenging—that’s a strong sign you’re moving in the right direction.

Facing Doubts Head-On: Time, Money, and Responsibilities

Most concerns fall into three main categories: the time commitment, financial realities, and balancing life responsibilities. Each is real and valid—but each can also be addressed with planning and support.

1. The Time Commitment: “Will I Be in Training Forever?”

The concern:

Medical training is long. You may be thinking:

- “If I start at 35, I won’t finish residency until my mid-40s.”

- “Will I have enough years left to practice and enjoy my career?”

- “Is it worth starting this late?”

Reframing the Timeline

A typical pathway might look like:

- 1–3 years: completing prerequisites and taking the MCAT

- 4 years: medical school

- 3–7 years: residency (depending on specialty)

- Optional: fellowship (1–3 additional years)

Yes, that’s a considerable investment. But compare it to your working life expectancy. If you’re 35 or 40, you likely have 25–30+ working years ahead. Many late-career physicians report 20+ fulfilling years in practice.

Instead of focusing on “how old I’ll be when I finish,” consider:

- “How do I want to spend the next 20–30 years of my working life?”

- “What will I regret more: starting late or never trying?”

Practical Strategies for Managing the Time Horizon

Create a realistic long-term plan

Sketch out a timeline that includes:- When you’ll complete prerequisites

- Target MCAT date

- Application cycle year

- Potential graduation and residency completion years

Choose specialties strategically

If time is a major concern, you might gravitate toward:- 3-year residencies (family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, psychiatry)

- Programs with a track record of supporting non-traditional residents

Leverage your maturity

Many older students are:- More efficient learners

- Better at time management

- Clear on their priorities

This can offset some of the perceived “late start.”

2. Financial Realities: Funding a Career Change to Medicine

The concern:

You may already have financial responsibilities: a mortgage, children, aging parents, or existing student loans. The cost of medical school can intensify fears about a career change.

Understanding the Financial Landscape

Key components:

- Tuition and fees (public vs. private can vary significantly)

- Living expenses (location matters—urban vs. rural, cost of housing)

- Opportunity cost (lost or reduced income while studying)

Actionable Financial Strategies

Do a full financial inventory

List current:- Income sources

- Debts (student loans, credit cards, mortgage)

- Fixed expenses

- Flexible expenses

Build a multi-phase budget

Plan separately for:- Prerequisite years

- MCAT and application year

- Medical school years

- Transition into residency (when salary resumes, but often at a lower level)

Explore funding sources specifically for non-traditional students

- Scholarships and grants for career-change students, first-generation applicants, or those entering shortage specialties (e.g., primary care, rural health)

- Federal and institutional loans

- Loan repayment or forgiveness programs for working in underserved areas (e.g., National Health Service Corps, state loan repayment programs)

Leverage your existing skills

Many non-traditional students maintain:- Part-time or consulting work based on prior careers

- Remote or flexible jobs during prereqs or gap years

- Occasional income (weekends, evenings) during med school, if allowed and manageable

Meet with a financial advisor

Ideally one familiar with medical training, to:- Plan for retirement despite delayed high-earning years

- Strategize around existing and future loans

- Protect your family with appropriate insurance

The key is not to ignore the financial realities, but to face them early and build a realistic, flexible plan.

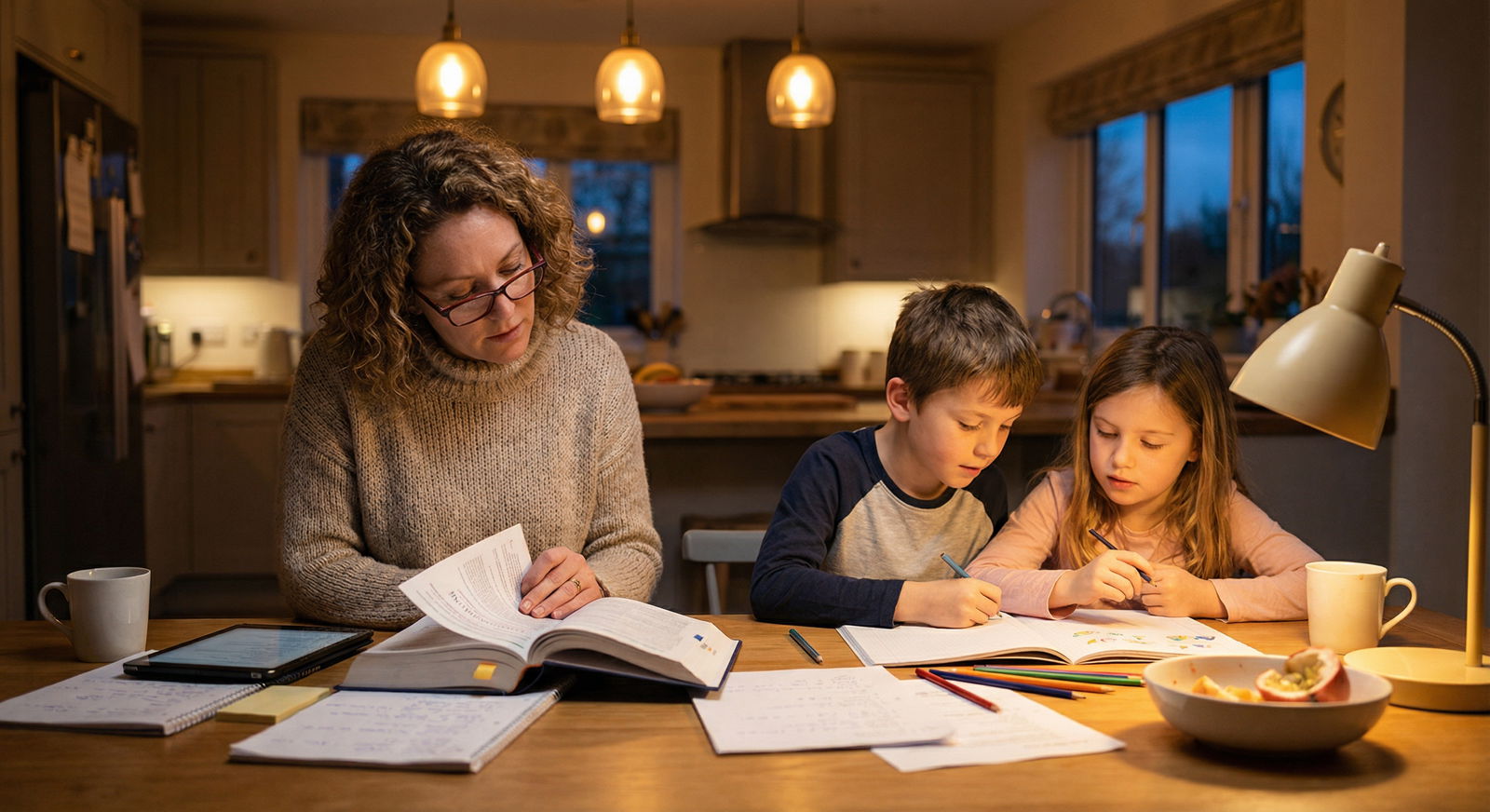

3. Balancing Family, Work, and Medical Training

The concern:

You may be worried about being present for your partner, kids, or other dependents while tackling a demanding medical career.

Proactive Communication and Boundary Setting

Have early, honest conversations with your family:

- Explain the training pathway and time demands

- Discuss what might change (income, schedules, relocation)

- Ask for their hopes, fears, and suggestions

- Involve older children where appropriate—they often rise to the occasion when they feel included

Design a realistic weekly schedule

- Block off non-negotiable family time

- Set dedicated study blocks and protect them

- Consider support systems: childcare, carpooling, meal prep, shared chores

Expect the plan to evolve

As you move from prereqs to med school to residency, your strategies will change. Build flexibility into your expectations.

Prioritizing Well-Being

Burnout can affect both you and your family if self-care is neglected. Consider:

- Regular exercise, even in brief intervals

- Simple, consistent sleep routines when possible

- Quick mental resets (walks, guided meditation, journaling)

- A therapist or counselor, especially during major transitions

Your capacity to care for others—patients and family—depends heavily on how you care for yourself.

Real Stories: Non-Traditional Students Who Made the Leap

Hearing how others navigated similar doubts can make your own path feel more achievable. While every journey is unique, certain themes recur: clarity of purpose, strategic planning, and strong support networks.

Case Study: Dr. Farah Ahmed – From Law to Medicine

In her mid-30s, Farah was a successful corporate lawyer with a stable income and a young family. On paper, she was thriving—but she felt disconnected from the day-to-day impact of her work.

After volunteering at a local free clinic as a translator, she realized how deeply she valued being part of patients’ healing journeys. Her doubts were intense:

- Walking away from an established legal career

- Taking on debt after already paying off law school loans

- Managing two young children while returning to full-time study

How she navigated it:

- Took evening and online science courses over three years while continuing part-time legal work

- Built a clear financial plan with her partner, including downsizing housing temporarily

- Found a mentor—a physician who had also transitioned from another career in her 30s

- Told her story authentically in her application, highlighting advocacy, communication skills, and her understanding of complex systems

Today, Dr. Ahmed is an attending physician working in an underserved community, where her background in law enhances her advocacy for health equity, policy change, and patient rights.

Case Study: Dr. Michael Chen – From IT Consultant to Preventive Medicine

Michael spent over a decade as an IT consultant in his 20s and 30s. He enjoyed solving complex problems but longed for more direct human connection. After helping build an electronic health record system and working closely with clinicians, he realized he wanted to be the one providing care.

At 40, with school-aged children and a spouse with a demanding career, he decided to pursue medical school.

Key strategies:

- Used his project management skills to create detailed study schedules and family calendars

- Kept some limited consulting work during his post-bacc program to stabilize finances

- Chose a specialty aligned with his interests and strengths—preventive medicine and informatics—where his tech background became an asset

- Throughout medical school, leaned into his age and experience as strengths in team settings

Dr. Chen is now a leader in integrating technology and preventive care, illustrating how prior careers can enrich—not hinder—a medical career.

Step-by-Step Roadmap: How to Transition into Medicine in Your 30s and 40s

Once you’ve clarified your motivation and examined your doubts, the next step is building a concrete plan for your career change.

1. Research Medical Schools and Pathways for Non-Traditional Students

Not all medical schools are the same, especially when it comes to supporting non-traditional students.

Key Factors to Evaluate

- MD vs. DO programs

- Both paths produce fully licensed physicians

- DO programs may emphasize holistic care and sometimes attract more non-traditional applicants

- Support for non-traditional students

Look for:- Older average matriculant age

- Formal advising for career-changers

- Part-time or flexible post-bacc affiliations

- Student organizations for non-traditional or “second-career” students

- Curriculum structure

- Systems-based vs. traditional curricula

- Pass/fail grading vs. tiered grading in pre-clinical years

- Early clinical exposure vs. heavy initial classroom focus

Collect this information from school websites, virtual info sessions, forums, and current medical students.

2. Complete Prerequisite Coursework Strategically

Most medical schools require foundational science coursework, often within the last 5–10 years:

- General biology (with lab)

- General and organic chemistry (with lab)

- Physics (with lab)

- Biochemistry

- Math (often statistics)

- English/writing-intensive courses

Options for Completing Prereqs

Formal post-baccalaureate programs

- Structured, often with advising and committee letters

- Some offer linkage agreements to certain medical schools

- May be more expensive but provide a clear framework

DIY/post-bacc at community colleges or universities

- More flexible and often more affordable

- You design your own course sequence

- Still well-respected if you perform strongly, especially in upper-level university sciences

Online coursework

- Growing acceptance post-pandemic, but policies vary

- Labs may need to be in-person at some institutions

Aim for strong grades in recent science coursework—this demonstrates academic readiness, especially if your earlier GPA was modest or in a different field.

3. Build Clinical, Research, and Service Experience

As a non-traditional applicant, admissions committees want to see that you understand what a medical career entails and have tested your interest in real settings.

Clinical experience

- Volunteering in hospitals, free clinics, long-term care facilities

- Scribing, EMT work, medical assistant roles

- Shadowing physicians across specialties

Research (optional but helpful)

- Basic science, clinical, health services, or public health research

- Particularly valuable if you’re interested in academic medicine, competitive specialties, or MD/PhD pathways

Service and leadership

- Longstanding community engagement (e.g., tutoring, social work, crisis lines)

- Committee roles, advocacy work, or leadership in organizations

As a career-changer, you likely already have transferable leadership, teamwork, and communication experience—be intentional in connecting those experiences to medicine.

4. Prepare Intentionally for the MCAT

The MCAT can feel intimidating if you’ve been out of school for years, but older students regularly succeed with the right approach.

- Create a study timeline (often 4–9 months, depending on your background and schedule)

- Use high-yield resources: comprehensive prep books, reputable question banks, and official AAMC materials

- Incorporate active learning: practice questions, review of missed items, teaching concepts aloud

- Simulate test day with full-length, timed practice exams in realistic conditions

If your schedule is tight due to work or family:

- Plan fewer but longer weekly study blocks

- Consider taking annual leave around the exam date

- Join or form a focused MCAT study group, ideally with other non-traditional students

Your MCAT performance can help reassure committees about your academic readiness, especially if your undergraduate grades are older or mixed.

5. Craft a Compelling Application That Highlights Your Non-Traditional Path

Your background is an asset, not a liability. The key is to frame it thoughtfully.

Personal statement

- Tell a coherent story of your career change: what led you here, what you’ve done to explore medicine, why now

- Highlight growth, resilience, and specific experiences that shaped your interest

Experience descriptions

- Emphasize impact in your prior career and in healthcare-related roles

- Draw parallels: leadership, communication, problem-solving, ethical decision-making

Letters of recommendation

Include:- At least two science faculty who can speak to your academic performance

- One or more supervisors (clinical, professional, or research) who can describe your work ethic and maturity

Secondary essays

Many schools specifically ask about non-traditional backgrounds—use these to:- Address academic red flags in a concise, growth-focused way

- Show how your prior life experience will contribute to their class and to medicine

6. Prepare Thoughtfully for Interviews

Your interview is where your story comes alive.

Anticipate questions specific to career change

- “Why medicine, and why now?”

- “How have your past experiences prepared you for this path?”

- “How will you manage the challenges of training at this stage in life?”

Practice articulating your journey

- Conduct mock interviews with mentors, peers, or advisors

- Be honest about your doubts—but frame them alongside the concrete steps you’ve taken to address them

Lean into your strengths

Maturity, perspective, professionalism, and rich life experience often make non-traditional applicants especially compelling.

Frequently Asked Questions About Starting Medicine in Your 30s or 40s

1. Is it really not too late to start medical school in my 30s or 40s?

No, it’s not too late. Medical schools increasingly value non-traditional students because they bring maturity, perspective, and diverse skills. Many people start medical school after other careers—teachers, engineers, nurses, business professionals, military veterans, and more.

What matters most is your:

- Clear motivation and understanding of the medical career

- Recent academic performance in rigorous science coursework

- Demonstrated commitment through clinical exposure and service

If you can show that you’ve thought carefully about this career change and prepared intentionally, your age becomes an asset rather than a barrier.

2. How can I be sure a medical career is the right career change for me?

You can’t remove all uncertainty, but you can significantly reduce it by:

- Spending substantial time in clinical settings (shadowing, volunteering, working)

- Speaking with physicians and current medical students—especially those who were non-traditional

- Reflecting honestly on what you enjoy day-to-day: do you like problem-solving, working under pressure, and being with people in vulnerable moments?

- Taking a science course to see how you handle academic material again

If, after these steps, you still feel drawn to medicine—even with full awareness of the challenges—that’s a strong indication you’re on the right track.

3. What if I can’t afford to stop working completely for school?

Many non-traditional students don’t stop working all at once. Some options:

- Continue full-time or part-time work while completing prerequisites

- Transition to remote, consulting, or flexible roles based on your current expertise

- Reduce work hours gradually as you approach the MCAT and application cycle

- In medical school, some students do limited side work (tutoring, prior-career consulting) when allowed and manageable

It’s crucial to:

- Build a realistic budget and timeline

- Seek out scholarships, grants, and loan repayment programs

- Talk with financial aid offices early in the process

4. Will I face bias or discrimination in medical school or residency because I’m older?

Experiences vary, but many non-traditional students report feeling welcomed and respected. Most programs recognize that:

- Older students often bring strong professionalism and teamwork skills

- Life experience enhances patient communication and empathy

- Diversity in age and background benefits the learning environment and patient care

You may occasionally encounter assumptions or comments about age, but you can:

- Respond calmly and confidently, focusing on your strengths

- Seek out supportive peers, faculty, and mentors

- Choose schools and programs known for valuing diversity, including age diversity

5. How can I support my family and maintain relationships during training?

Family support is both critical and possible with planning:

- Have early, transparent conversations about what medical school and residency involve

- Involve partners and older children in scheduling and problem-solving

- Protect specific times for family (e.g., weekly dinners, phone calls, short outings)

- Consider living close to extended family or support networks if relocation is needed

- Use institutional resources—many medical schools offer counseling, family support groups, and wellness programming

Your family can be a powerful source of motivation and perspective throughout your training.

Conclusion: Your Non-Traditional Path Is a Strength, Not a Detour

Pursuing a medical career in your 30s or 40s is undeniably a bold choice—but bold does not mean reckless. When you pair thoughtful self-reflection with strategic planning, your “late start” becomes a powerful advantage.

You bring:

- Lived experience that deepens your empathy

- Mature decision-making and professionalism

- Skills from previous careers—communication, leadership, problem-solving—that are invaluable in medicine

- A clear, tested conviction that this career change truly matters to you

Your doubts are not signs to stop; they are signposts, guiding you toward the questions you need to answer and the plans you need to build. With deliberate preparation, honest conversations, and the right support network, you can absolutely make the leap to medicine later in life.

The medical profession needs physicians who can connect with patients from all walks of life—including those navigating midlife transitions, career changes, and complex responsibilities. Your journey as a non-traditional student doesn’t make you an outlier; it makes you exactly the kind of doctor many patients are waiting for.