The most impressive premed volunteering is rarely in the official brochure—and admissions committees know it.

Most applicants crowd into the same 3–4 predictable roles: generic hospital volunteer, medical scribe, crisis hotline, EMT. None of those are bad. But they have become background noise. What stands out now are niche roles that show you are willing to do unglamorous, specific, longitudinal work that clearly connects to patient care and health systems.

Let me break this down specifically.

You are not trying to “check the volunteering box.” You are trying to build a portfolio of roles that, taken together, prove three things:

- You understand real patient needs, not just what premed forums talk about.

- You can function in complex, imperfect healthcare settings.

- You choose commitments that cost you something—time, emotional energy, or comfort—but still show up consistently.

Below are niche volunteer roles that reliably demonstrate authentic commitment to medicine, how to find them, and how to talk about them so they land with admissions committees.

(See also: Maximizing Upper‑Division Biology Courses for Future Med Retention for more details.)

1. Medical-Legal Partnership & Health Advocacy Roles

Medical schools are increasingly obsessed with social determinants of health. They want students who understand that a patient’s blood pressure is not just about medication—it is about eviction notices, food insecurity, transportation, immigration status, and unpaid bills.

Most premeds say “I care about health disparities.” A much smaller subset can say, “I spent 2 years helping patients file Medicaid appeals and housing support forms through a medical-legal partnership.”

What this role actually looks like

Medical-legal partnerships (MLPs) place legal aid services inside clinics and hospitals. Volunteers may:

- Help patients complete:

- Medicaid/Medicare applications

- SNAP (food stamps) forms

- Disability benefits paperwork

- Housing assistance or eviction defense documentation

- Assist with medical debt negotiations or charity care applications

- Gather documentation for disability accommodations

- Coordinate with social workers, case managers, and sometimes attorneys

You are not practicing law. You are facilitating access to systems that determine whether your patient can afford food, medication, or rent.

Why admissions committees take this seriously

This kind of role shows:

- Systems-level awareness: You understand that prescriptions mean very little if a patient is sleeping in a car or losing coverage.

- Tolerance for bureaucracy: You can tolerate slow, frustrating work—exactly what medicine often feels like.

- Longitudinal service: These programs value consistency; you often follow similar patient populations over time.

How to find or create it

Look for:

- “Medical-legal partnership” + your city

- “Health advocacy volunteer” at safety-net hospitals or community clinics

- Legal aid organizations partnered with hospitals

If no formal program exists, approach:

- A local free clinic or FQHC (Federally Qualified Health Center)

- A law school clinic associated with your university

- Hospital social work departments

Offer to help with non-legal tasks: form completion, call-backs, resource navigation. Over time, you can carve out a defined volunteer role.

How to talk about it in applications

Weak version:

“I helped patients with paperwork at a clinic.”

Stronger, specific version:

“Over 18 months at a medical-legal partnership embedded in a safety-net clinic, I helped 120+ patients complete Medicaid re-enrollment, disability, and housing benefit forms. One patient’s hypertension stabilized only after we secured housing; that changed how I think about what counts as ‘treatment.’”

2. Longitudinal Work With Vulnerable Subpopulations

Every premed says they “like working with people.” Far fewer can demonstrate they stayed with a single vulnerable population for years. That longitudinal pattern is what reads as authentic commitment.

Examples of niche longitudinal roles

Clinic-based refugee health navigator

- Help newly arrived refugees:

- Schedule and attend medical appointments

- Arrange interpreters

- Understand vaccination requirements

- Navigate school physicals and TB tests

- Often coordinated through:

- Resettlement agencies (IRC, Catholic Charities, Jewish Family Services)

- Refugee health programs at academic medical centers

- Help newly arrived refugees:

HIV clinic volunteer with adherence support

- Reminders and support around:

- ART adherence

- Transportation for appointments

- Lab follow-up

- You see the same patients repeatedly, which builds trust and insight into chronic disease management.

- Reminders and support around:

Homeless shelter–clinic liaison

- Work at the intersection of:

- Overnight shelters

- Mobile health vans

- Street medicine teams

- Roles include:

- Intake support

- Health education

- Tracking follow-up visits

- Work at the intersection of:

Pediatric complex-care companion

- For children with:

- Cystic fibrosis

- Spina bifida

- Congenital heart disease

- Severe developmental delay

- Volunteers assist with:

- Play and stimulation during long admissions

- Parent respite support

- Appointment coordination and logistics

- For children with:

Why this category is powerful

- It shows you can sustain relationships, not just drop into a one-day service event.

- You become familiar with the trajectory of disease and treatment.

- You see the emotional burden on patients and families over time, not just in a single snapshot.

What committees infer about you

If they see 2–3 years with a single subpopulation (e.g., “Refugee Health Navigator, 8 hrs/week, 2.5 years”), they infer:

- You can commit beyond what your premed advisor told you was needed.

- You probably have specific stories and ethical tensions you have wrestled with.

- You have seen medicine fail, not just succeed—and chose to remain engaged.

3. Non-Glory Hospital Roles That Actually Matter

Most students fight for “patient-facing” positions and overlook the support roles that keep hospitals functioning. Ironically, some of the most meaningful premed experiences come from unglamorous jobs that show you respect the entire care team.

Examples of undervalued but high-yield roles

Central supply / materials management volunteer

- Tasks:

- Stocking crash carts

- Transporting sterile supplies

- Assembling procedure kits

- What you learn:

- How a hospital actually moves: which units are always short on supplies, what happens during code situations, how logistics affect patient care.

- Reflection angle:

- You see that a “simple” missing catheter or line kit can delay procedures and change outcomes.

- Tasks:

Discharge logistics volunteer

- Tasks:

- Escorting patients to transportation

- Reviewing basic discharge packets (not medical advice, but logistics: pharmacy locations, follow-up visit scheduling)

- What you observe:

- Confusion around discharge instructions

- Families attempting to manage complex regimens

- Reflection angle:

- Insight into why readmissions happen and how “transition of care” is more fragile than students realize.

- Tasks:

Operating room turnover volunteer

- Tasks:

- Assisting with non-sterile room prep

- Moving patients (under staff supervision)

- Coordinating equipment and instrument trays

- What you learn:

- Teamwork dynamics between surgeons, nurses, techs, anesthesia

- Time pressure and coordination required to keep an OR schedule moving

- Tasks:

Why these roles signal authenticity

Adcoms have read thousands of essays that center on “I held a patient’s hand in the ED and realized I wanted to be a doctor.” They see far fewer that say:

- “I stocked crash carts for 2 years and saw how overlooked work affects patient safety.”

- “I helped discharge patients and watched how easily critical information was lost between hospital and home.”

Students willing to engage with the “infrastructure” of care—supply chains, discharge processes, OR turnover—often make more grounded, systems-aware physicians.

4. Tech and Accessibility Support for Patients

If you understand technology, you have an underutilized way to serve patients that falls squarely in the “niche but impactful” category.

Patient-facing tech roles

Telehealth onboarding assistant

- Teach patients how to:

- Log into patient portals

- Use video visit platforms

- Upload home blood pressure or glucose readings

- Often needed in:

- Primary care clinics

- Geriatric practices

- Rural telemedicine programs

- Teach patients how to:

Assistive device and accessibility volunteer

- Help patients with:

- Basic screen-reader setup

- Font enlargement on phones

- Voice commands for mobility-limited users

- Partner organizations:

- Low-vision clinics

- Rehabilitation hospitals

- Disability advocacy nonprofits

- Help patients with:

Remote monitoring program assistant

- Support for:

- Home blood pressure cuffs

- Wearables for heart failure or COPD

- App-based medication reminders

- You may:

- Train patients

- Troubleshoot connectivity issues

- Gather qualitative feedback on what actually works for them

- Support for:

Why this reads as “future-oriented”

Medicine is moving rapidly toward:

- Telehealth

- Remote monitoring

- Digitally mediated care

Students who have not only used these systems, but have taught them to vulnerable patients, come in with a meaningful advantage.

Your takeaways become:

- Digital divides are real and often overlap with age, language, and socioeconomic status.

- A “cool new platform” means nothing if half your patients cannot log in.

How to pitch this experience in an interview

“I volunteered as a telehealth onboarding assistant in a geriatric clinic. At first I thought it would be mostly tech support. Over time I realized I was actually doing health equity work—helping patients who lived 2 hours away and could not drive get reliable access to their physician. The biggest barrier was not interest but fear and confusion about the technology. That reshaped how I think about implementing any new medical innovation.”

5. Volunteer Roles Embedded in Interdisciplinary Teams

One of the strongest predictors that you understand modern medicine: you have spent real time in spaces where physicians are just one member of the team.

Not shadowing from the corner of a room. Embedded in a process where your contribution, even if small, affects the workflow.

High-yield interdisciplinary environments

Palliative care teams

- Roles:

- Family meeting coordination

- Resource compilation

- Follow-up phone calls about support services (not medical advice)

- What you see:

- Delicate goals-of-care conversations

- Interplay between spiritual care, social work, and medicine

- Roles:

Geriatric or memory clinic programs

- Roles:

- Cognitive screening assistance

- Caregiver support group logistics

- Education materials development

- You gain insight into:

- Polypharmacy

- Functional status vs. diagnosis

- Family dynamics and caregiver burnout

- Roles:

Rehabilitation teams (PT/OT/SLP)

- Settings:

- Stroke rehab units

- Spinal cord injury centers

- Volunteer work:

- Patient transport between therapies

- Group exercise or fine-motor activity support

- You witness:

- Slow, incremental progress

- The emotional arc of recovery and adaptation

- Settings:

Integrated behavioral health in primary care

- Roles:

- Patient check-ins and survey administration (PHQ-9, GAD-7 under supervision)

- Coordination between behavioral health and primary care teams

- Lessons:

- How mental health and physical health interact

- How stigma plays out in real time

- Roles:

Why this matters to admissions

Medicine is no longer a solo sport. Committees want to see that you:

- Understand non-physician roles and respect them.

- Can function in structured, team-based processes.

- Observed (and handled) situations where disagreement exists within the team.

You can explicitly connect this in your application:

“Working with a palliative care team taught me that my future role as a physician will be to guide and collaborate, not to dictate.”

6. Community-Based Roles Tied Directly to Health Outcomes

Community service only strengthens your application when it intersects concretely with health. “Food bank volunteer” is generic. “Nutrition navigator in a diabetes-food insecurity program” is niche and compelling.

Examples that move the needle

Food insecurity–clinic bridge

- Programs often called:

- “Food pharmacy”

- “Produce prescription”

- Volunteer tasks:

- Screening patients for food insecurity

- Packing disease-appropriate food boxes (e.g., low-sodium for heart failure)

- Coordinating pick-up/delivery aligned with clinic visits

- What you learn:

- Direct links between diet, chronic disease, and structural barriers.

- Programs often called:

Smoking cessation or addiction support programs

- Settings:

- Community centers

- FQHCs

- Mobile clinics

- Roles:

- Group session logistics

- Tracking attendance

- Follow-up reminder calls

- Reflection:

- You see ambivalence, relapse, and the chronic nature of addiction.

- Settings:

Violence intervention programs tied to trauma centers

- Roles:

- Nonclinical support to survivors of violence

- Helping connect them to counseling, job training, or schooling

- You encounter:

- Trauma not just as a physical injury but as a social and psychological event.

- Roles:

Asthma or COPD home visit support

- Tasks:

- Environmental triggers checklists

- Education material explanation

- Coordination between clinic and home

- Very powerful for:

- Demonstrating understanding of environmental health impacts.

- Tasks:

How this looks in your activity list

Instead of “Volunteer at community health fair,” you want something like:

“Volunteer Health Navigator – Produce Prescription Program

Partnered with a hospital-based program prescribing fresh produce to patients with uncontrolled diabetes and food insecurity. Screened patients, coordinated produce pick-up aligned with clinic visits, and followed up by phone about barriers to diet changes. Saw A1c improvements in several patients over months of engagement.”

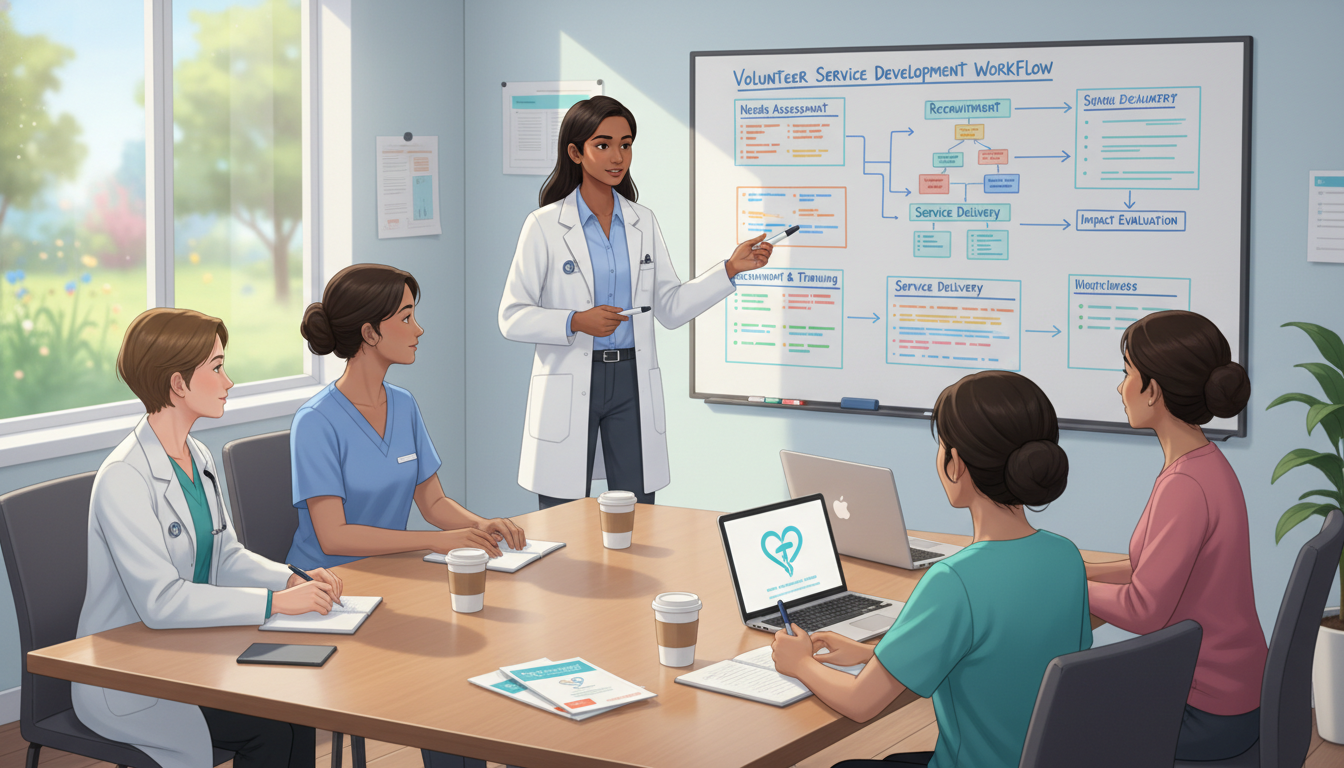

7. Building, Not Just Joining: Creating a Niche Role

Some of the most impressive roles are not found on a website. They are built by students who see a gap and design a sustainable response.

You do not need to create a fully independent nonprofit. In fact, admissions committees are wary of “premed vanity projects” that disappear when the creator graduates. The key is:

- Identify a real, repeated problem in a clinical or community setting.

- Design a role or small program that fits within existing structures.

- Pilot it, refine it, and hand it off to the next cohort.

Concrete examples

Language-concordant patient reminder program

- Problem:

- High no-show rates among non-English-speaking patients.

- Solution:

- Recruit bilingual students to:

- Call patients in their preferred language

- Confirm transportation

- Clarify instructions for fasting labs, prep, etc.

- Recruit bilingual students to:

- Sustainability:

- Formalize as a student-run organization

- Create training materials

- Partner with clinic administration

- Problem:

Inpatient family resource cart

- Problem:

- Families of long-stay pediatric patients lack basic comfort resources.

- Solution:

- With nursing and child life approval, develop:

- A volunteer-run cart with snacks, chargers, coloring books, basic toiletries

- With nursing and child life approval, develop:

- Reflection:

- Shows attention to caregiver burden and holistic care.

- Problem:

Digital literacy workshops embedded in clinic schedules

- Problem:

- Patients miss telehealth visits due to low digital literacy.

- Solution:

- Run 30-minute workshops in clinic waiting rooms:

- Creating email accounts

- Downloading and logging into the health portal

- Practicing a mock video visit

- Run 30-minute workshops in clinic waiting rooms:

- Problem:

How to present it without sounding performative

Focus less on “I started a program” and more on:

- The gap you addressed.

- The process of working with staff and adapting to constraints.

- The metrics or qualitative feedback you used.

- The transition plan when you leave.

For example:

“After noticing high no-show rates among Spanish-speaking patients in a primary care clinic, I worked with the clinic manager to pilot a language-concordant reminder call system staffed by bilingual students. Over 6 months, missed appointment rates dropped from 28% to 17% in our pilot group. I then wrote training protocols and onboarded two underclassmen to continue the program after I graduate.”

This reads as thoughtful, data-aware, and collaborative—not self-promotional.

8. How to Choose and Sequence These Roles Strategically

You do not need all of these. You need a coherent story built from a few carefully chosen, long-term commitments.

Good patterns vs. scattered activities

Stronger pattern:

- 1–2 longitudinal clinical roles:

- e.g., Refugee Health Navigator (2 years)

- Discharge Logistics Volunteer (1.5 years)

- 1–2 community or systems-level roles:

- e.g., Food Insecurity–Clinic Bridge (1 year)

- Telehealth Onboarding Assistant (1 year)

Weaker pattern:

- Ten unrelated short-term roles:

- 1 semester at a nursing home

- 1-day health fair

- 3-month hospital stint

- 2 months of remote tutoring

Committees can see the difference. They are reading your trajectory, not counting your line items.

Evaluating whether a role demonstrates “authentic commitment”

Ask yourself:

- Does this role put me in contact with real patients or caregivers, or the systems that directly affect them?

- Is there a way for me to stay involved for at least 12–24 months?

- Am I learning something about:

- Chronic illness

- Vulnerable populations

- Health systems and logistics

- Interprofessional teamwork

- Will I have at least 2–3 specific stories where I faced some tension, uncertainty, or emotional complexity?

If the answer is “no” to all of those, the experience may be fine for exploration, but it will not be a core pillar of your application.

Time commitment reality check

You can build a robust volunteering portfolio on:

- 3–6 hours per week during the semester

- 8–10 hours per week during summers

What matters is consistency and thoughtful reflection, not sheer volume. A 3-hour/week role sustained over 2 years is far more compelling than 15 hours/week for one month.

9. Reflection: Transforming Roles into Convincing Narratives

Simply having a niche role is not enough. You must be able to articulate what it changed in you.

When you reflect on these experiences, prioritize:

- Specific patients or moments (de-identified, of course)

- Ethical or emotional tensions

- Feeling helpless when social conditions blocked care

- Balancing empathy with role limitations

- Shifts in understanding

- From “medicine = diagnosis and treatment” to “medicine = systems, relationships, and long-term engagement”

For example, from a medical-legal partnership:

“I remember a patient whose disability claim had been denied twice. Our team gathered medical records, clarified documentation from his cardiologist, and helped file an appeal. When his claim was eventually approved, he did not talk about the money first. He said, ‘Now my kids will not have to drop out of school to work extra shifts.’ That was the first time I fully understood how a line in a chart translates into the life of a family. It reframed my understanding of what it means to ‘help a patient’.”

That kind of reflection signals maturity in a way no list of hours ever could.

Key Takeaways

- Niche volunteer roles that intersect directly with vulnerable populations, health systems, or interdisciplinary teams signal far deeper commitment than generic, short-term experiences.

- Longitudinal involvement—12–24+ months in a small number of thoughtfully chosen roles—speaks more loudly than a scattered collection of brief activities.

- Your ability to articulate how these roles changed your understanding of patients, systems, and the physician’s place within them is what ultimately convinces admissions committees that your commitment to medicine is authentic.