Only 8–10% of U.S. medical school applicants report a primary major in public health or health policy, yet adcoms consistently rate these applicants as having above-average readiness for population-level thinking and systems-based care.

Let me break down why that is, and more importantly, which specific public health courses actually move the needle for admissions committees.

Why Public Health Stands Out (When Done Correctly)

(See also: Advanced Study Skills for Pre‑Med Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry for tips on mastering challenging coursework.)

Medical schools are drowning in biology and neuroscience majors with nearly identical transcripts. When an application crosses the screen with “Public Health,” “Global Health,” or “Health Policy” as a major or minor, reviewers do not automatically think “easy route”; they think:

- “Can this applicant think beyond the individual patient?”

- “Do they understand systems, equity, and real-world health determinants?”

- “Will they be able to function in team-based, community-focused, value-based care models?”

The key nuance: simply putting “Public Health” on your degree audit is not impressive by itself. What impresses admissions committees is a coherent, rigorous course pattern that shows:

- Solid scientific foundation (you still must meet or exceed traditional premed expectations).

- Quantitative competency (especially biostatistics and data interpretation).

- Real engagement with population health, policy, and health disparities.

- Evidence that you can handle writing-, reading-, and discussion-intensive content.

You will see two broad categories on your transcript that adcoms read differently:

- “Box-checking” public health – low-level survey courses, minimal quantitative work, easiest-available sections.

- “Deliberate” public health – sequenced methods, epidemiology, higher-level seminars, integrated with strong sciences.

The rest of this guide focuses on building the deliberate version.

The Non-Negotiables: Science Core + Public Health Spine

Before we get into the specific public health courses that impress, you must understand the baseline: public health is an “and,” not an “instead of,” the classic premed core.

You still need:

- 2 semesters of general chemistry with lab

- 2 semesters of organic chemistry with lab (or 1 orgo + 1 biochem, depending on school)

- 2 semesters of biology with lab

- 2 semesters of physics with lab

- 1–2 semesters of college-level math (often statistics + calculus or higher-level math)

- 2 semesters of English / writing-intensive coursework

On top of that, a strong public health pathway typically has a methodological spine:

- Introductory public health

- Introductory epidemiology

- Biostatistics

- 1–2 higher-level methods or data courses

- 2–4 content-area electives (e.g., global health, health policy, environmental health)

Adcoms are looking for whether these pieces are present and logically sequenced.

Core Public Health Courses That Signal Seriousness

Here are the public health-focused courses that most reliably impress admissions committees, what they show, and how they connect to medicine.

1. Introduction to Public Health (or Foundations of Population Health)

Names you might see:

- “Introduction to Public Health”

- “Foundations of Public Health”

- “Global and Public Health”

- “Population Health and Society”

Why adcoms like it:

This is your conceptual anchor. It signals that you understand:

- The “10 Essential Public Health Services”

- Primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention

- Basic frameworks: health determinants, the public health system, surveillance

- The distinction between medicine (individual-level diagnosis and treatment) and public health (population-level prevention and promotion)

What it demonstrates:

- Breadth of awareness of how clinical care fits into a larger system.

- You are not thinking of physicians as solo heroes, but as part of multidisciplinary teams.

What to watch for:

If your intro course is well-regarded and writing-intensive (policy briefs, reflection papers, small-group discussion), mention that in secondaries or your activities descriptions. It shows you can handle non-multiple-choice intellectual work.

2. Epidemiology: The Single Most Valuable Public Health Course

Names you might see:

- “Introduction to Epidemiology”

- “Epidemiologic Methods”

- “Principles of Epidemiology”

If you only take one “real” public health methods course, make it this one.

Why adcoms notice it immediately:

Epidemiology directly parallels how physicians need to think:

- Study design → interpreting medical literature and clinical trials

- Measures of association (risk ratio, odds ratio, hazard ratio) → understanding evidence behind treatments

- Confounding, bias, effect modification → critical appraisal of research

- Screening test metrics (sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV) → core clinical reasoning

An A in a solid epidemiology course tells committees:

- You can handle abstract, quantitative reasoning.

- You can interpret and critique data rather than simply memorizing facts.

- You will not be lost when M1 Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) blocks begin.

Course features that make it especially impressive:

- Use of R, STATA, SAS, SPSS or similar software for basic analysis.

- Real data sets (NHANES, BRFSS, hospital data) used for projects.

- A final project requiring you to design or analyze a study.

If your epidemiology course is at the 300- or 400-level and methodologically oriented (not just a descriptive “history of outbreaks” class), it carries substantial weight.

3. Biostatistics: Evidence Literacy in Transcript Form

Names you might see:

- “Biostatistics”

- “Applied Biostatistics in Public Health”

- “Statistical Methods in Health Sciences”

This is where many premeds try to take the path of least resistance.

Adcoms notice two patterns:

- Generic “easy stats” (sometimes housed in psychology, sociology, or general ed) with minimal math, mostly conceptual.

- Real biostatistics with probability, regression, confidence intervals, and data analysis.

Guess which pattern makes them question your readiness versus which one makes them confident you can handle medical school’s evidence-based demands.

Core topics that impress:

- Descriptive statistics (means, medians, SDs) + basic data visualization

- Probability distributions, standard error, central limit theorem (even at high level)

- Confidence intervals, p-values, Type I/II error

- T-tests, chi-square, ANOVA, correlation

- Simple linear and logistic regression

If you use R, STATA, or SPSS for labs, note that in your activities or secondaries. It demonstrates “quantitative public health,” not just vocabulary-level biostat.

Signals to committees:

- Comfort with quantitative reasoning and interpretation.

- Capacity to read and critique the Methods and Results sections of journal articles.

- Preparedness for QM- and EBM-heavy curricula (e.g., Harvard, Michigan, Vanderbilt).

4. Health Policy and Management: Understanding the System You Will Work In

Names you might see:

- “Health Policy and Management”

- “Health Care Systems and Policy”

- “U.S. Health Care System”

- “Health Economics and Financing”

Very few premeds have a coherent understanding of how healthcare is organized and financed. That is why these courses stand out.

Strong policy/management courses cover:

- U.S. health care structure: Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, ACA.

- Cost, access, and quality trade-offs.

- Value-based care, accountable care organizations (ACOs), bundled payments.

- Basic health economics: incentives, moral hazard, market failures.

- Organizational behavior in healthcare settings.

Why this impresses adcoms:

- Shows maturity: you know medicine is not practiced in a vacuum.

- Indicates potential leadership and systems-thinking orientation.

- Aligns well with mission-driven schools focused on health systems improvement (e.g., UCSF, Duke, Penn).

These courses can also give you concrete things to talk about in interviews:

- A policy case study you analyzed.

- A simulation where you managed a “hospital” budget.

- A paper you wrote about Medicaid expansion and outcomes.

5. Social and Behavioral Determinants: Health Equity on Your Transcript

Names you might see:

- “Social and Behavioral Foundations of Public Health”

- “Social Determinants of Health”

- “Race, Ethnicity, and Health”

- “Health Disparities and Social Justice”

Virtually every medical school now talks about social determinants, structural racism, and health equity. Most applicants can recite definitions; far fewer have taken rigorous coursework that forces them to engage with data, theory, and history.

What strong courses demonstrate:

- You understand models like the socioecological model and fundamental cause theory.

- You have been exposed to literature on bias, discrimination, and structural racism in health.

- You can talk about disparities with nuance, not just slogans.

These courses become especially powerful if:

- You pair them with community-engaged work or public health research.

- You can articulate in your personal statement how what you learned shaped your understanding of clinical practice.

Adcoms notice when someone moves beyond “I want to serve the underserved” to “Here are the specific upstream mechanisms creating the patterns I see in clinic.”

6. Environmental and Global Health: Breadth With Real-World Relevance

Not required, but often excellent differentiators.

Environmental Health

Names you might see:

- “Environmental and Occupational Health”

- “Global Environmental Health”

- “Climate Change and Health”

Why it matters:

- Physicians will increasingly face climate- and environment-related conditions: heat illness, air pollution-related asthma and COPD, vector-borne diseases shifting geographically.

- Shows you understand exposures, dose-response relationships, and risk assessment.

Global Health

Names you might see:

- “Global Health: Challenges and Responses”

- “Global Burden of Disease”

- “Global Health Policy and Programs”

Adcoms look for:

- Critical perspective (not “voluntourism” glorification).

- Discussion of ethics, power dynamics, and sustainability.

- Use of metrics like DALYs, QALYs, and burden-of-disease frameworks.

Impressive pattern: you take a rigorous global health course, then engage in research or long-term partnerships rather than a one-week trip.

Advanced and Methods-Heavy Courses That Really Jump Off the Page

Once you have the core (Intro, Epi, Biostats, Social/Behavioral, Policy), the next set of courses can turn a “nice” public health transcript into a “this person is going to be a physician-leader” transcript.

1. Advanced Epidemiologic Methods or Data Analysis

Course names:

- “Intermediate Epidemiologic Methods”

- “Advanced Epidemiology”

- “Applied Epidemiologic Data Analysis”

- “Longitudinal Data Analysis in Public Health”

These scream serious quantitative training. Adcoms know that a student who can:

- Understand cohort vs. case-control nuance.

- Work with survival analysis or longitudinal data.

- Adjust for confounders properly.

…will have an easier time in any research track, MD/MPH, or academic medicine pathway.

2. Health Services Research or Outcomes Research

Names:

- “Health Services Research Methods”

- “Comparative Effectiveness Research”

- “Outcomes and Quality Measurement in Health Care”

Signals:

- You are already thinking about quality metrics, cost-effectiveness, and real-world outcomes.

- Especially appealing to schools with strong health services research centers (e.g., Michigan IHPI, Dartmouth, Brown, UCSF).

3. Program Evaluation, Implementation Science, or Quality Improvement

These are less common at the undergraduate level, but extremely attractive when present.

They demonstrate:

- Skill in designing, implementing, and evaluating real interventions.

- Preparation for QI projects that are now baked into many medical school curricula and residency requirements.

If your school offers an undergraduate course on “Quality Improvement in Health Care” or “Program Planning and Evaluation,” that is worth serious consideration.

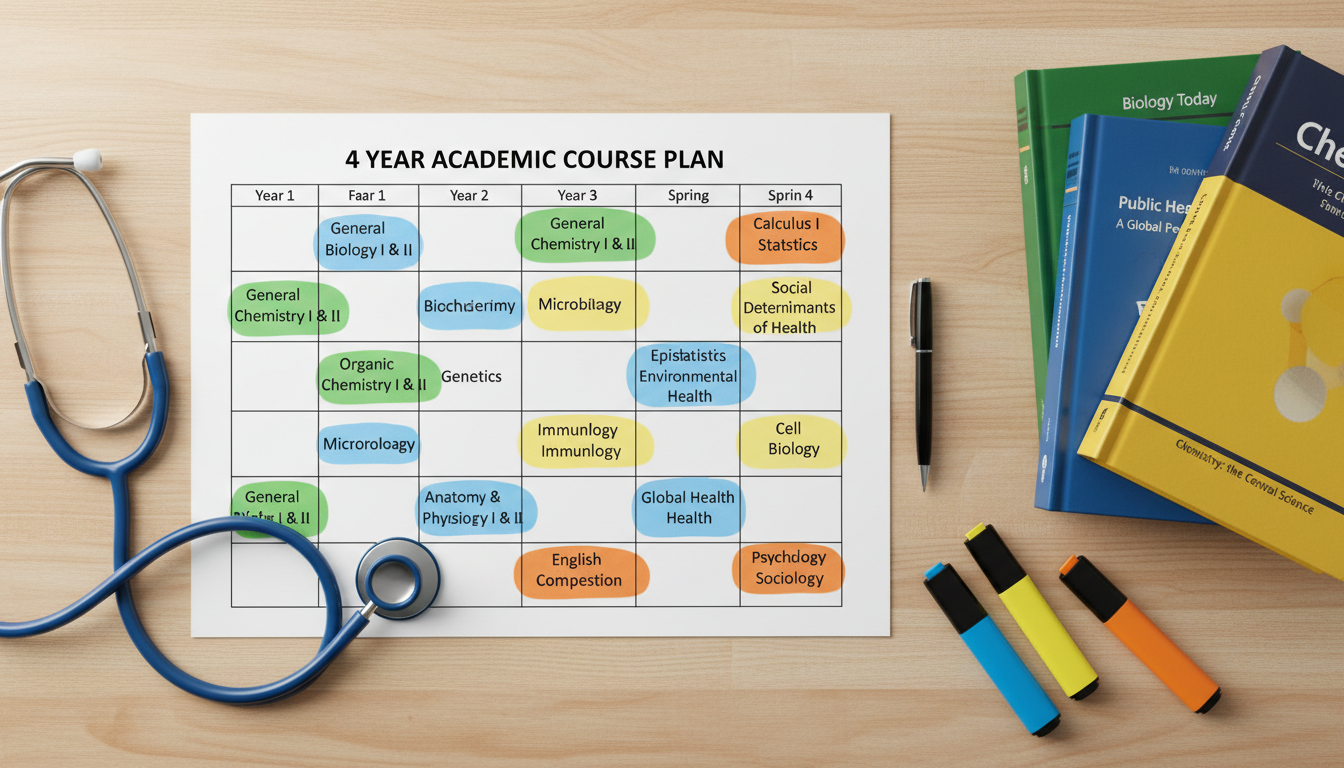

How to Build a Four-Year Plan That Makes Sense to Adcoms

Here is a rough model of a strong Public Health + Premed structure over four years. Obviously you will adjust for AP credits, transfer credits, and institutional quirks.

Year 1: Lay the Science and Conceptual Foundation

- General Chemistry I & II + lab

- Biology I (or II, depending on sequence) + lab

- Writing / English course

- Intro to Public Health (or Foundations of Population Health)

- General education requirement(s)

Purpose:

- Show you can handle college-level science while exploring public health.

- Begin building the “narrative spine” of your interest in population health in a low-stakes way.

Year 2: Methods Start + Continuing Core Sciences

- Organic Chemistry I & II + lab

- Biology II + lab

- Physics I (with lab)

- Biostatistics (ideally Biostats-in-Public-Health rather than generic stats)

- Social and Behavioral Determinants or Health Disparities

Purpose:

- Begin your quantitative public health training (Biostats).

- Demonstrate you can balance heavier science loads with writing/reading-intensive courses.

This is a good year to begin research in public health or health services, which pairs very naturally with Biostats/Epi.

Year 3: Epi, Policy, and Depth

- Physics II + lab

- Introduction to Epidemiology

- Health Policy and Management / U.S. Health Care System

- 1–2 public health electives (e.g., Environmental Health, Global Health)

- Possibly Advanced Methods if prerequisites are met

Purpose:

- Cement the core of your public health narrative and skills before you apply.

- Provide rich material for your personal statement, work/activities, and secondary essays.

- Set you up to talk in interviews about specific projects, policy topics, or Epi/biostats skills.

MCAT timing: Many public health-oriented premeds take the MCAT at the end of this year, leveraging their strong social sciences background for the Psych/Soc section.

Year 4: Advanced Work and Capstone

- Any remaining prereqs (often Biochemistry is here)

- Advanced Epidemiology / Data Analysis / Health Services Research

- Senior seminar or capstone in Public Health

- Focused electives aligned with your interests (e.g., Maternal & Child Health, Mental Health Policy, Urban Health)

Purpose:

- Signal continued rigor even after applying.

- If you are on MD/MPH radar, this is where that preparation becomes obvious.

How This Course Set Translates to MCAT Strengths

Public health coursework, when chosen carefully, pays dividends on the MCAT.

Psychological, Social, and Biological Foundations (P/S):

Social determinants, health behavior theories, disparities, and community health content map almost directly to this section. Students with health disparities and social/behavioral coursework often report P/S section scores in the 129–132 range.Critical Analysis and Reasoning Skills (CARS):

Reading-heavy seminars, policy analysis papers, and theory courses sharpen your ability to dissect arguments. You get used to parsing dense, unfamiliar texts — exactly what CARS asks.Chemical and Biological Foundations (Chem/Phys, Bio/Biochem):

You still need traditional science rigor. Public health will not rescue a weak science foundation. However, Biostatistics and Epidemiology sharpen your comfort with graphical data, tables, and experimental designs, which show up frequently.

Adcoms do pay attention when someone has:

- Solid to strong science grades (A-/B+ or better in the core).

- High P/S and CARS MCAT scores.

- A transcript full of Epi, Biostats, Health Policy, and Social/Behavioral courses.

That combination signals both scientific readiness and broad, systems-level thinking.

How to Talk About Your Public Health Courses in Applications

Course selection alone does not tell your story. You have to translate it.

In the Personal Statement

Avoid:

“I chose public health because I am passionate about helping underserved communities.”

Better:

Anchor on a specific course or project:

“In ‘Epidemiology of Chronic Disease,’ I worked with county diabetes surveillance data to identify clusters of uncontrolled HbA1c…”Show the bridge from classroom to clinic:

“Working through the trade-offs of screening guidelines in Epi made me view individual patient decisions as part of population-level risk management, rather than isolated encounters.”

In Work & Activities

When describing research or community work tied to your public health coursework:

- Explicitly name the methods you used: logistic regression, thematic analysis, QI cycles.

- Connect your Biostats/Epi skills to concrete outputs: abstracts, posters, program evaluations.

- Mention if an assignment or project originated in a course and evolved into something larger.

In Secondaries and Interviews

Questions like “Why MD/MPH?” or “How will you contribute to our focus on community health?” are where your transcript becomes very helpful.

Reference:

- Specific policy debates you studied.

- A mini-program evaluation you completed.

- How a disparities course changed your view of a clinical interaction you shadowed.

Common Pitfalls Public Health Premeds Fall Into

Adcoms have seen the following patterns often enough that they raise red flags:

Lightweight science + heavy public health

- Multiple B-/C grades in orgo, physics, and biochem, while getting As in policy and disparities courses.

- Interpretation: “Likes talking about health but struggles with the scientific foundation.”

All survey courses, no methods

- “Intro to Global Health,” “Global Diseases,” “Health and Society” — but no Biostats, no Epi.

- Interpretation: “Interest in big-picture concepts, but little evidence of quantitative rigor.”

Early public health, then abandoning rigor

- Strong intro work, then an upper-division transcript filled with the easiest electives.

- Interpretation: “Front-loaded seriousness; may not sustain effort when content becomes complex.”

Mismatch between narrative and coursework

- Essays focus on health policy and systems change, but transcript shows almost no policy or systems courses.

- Interpretation: “Buzzword-heavy but not backed by training.”

Avoid these by ensuring that your methods core is non-negotiable and that your upper-level courses match your stated interests.

Brief Summary: What Adcoms Actually Want to See

Two or three structural elements make a public health premed path stand out:

- A rigorous spine: Intro to Public Health → Biostats → Epidemiology → at least one advanced or methods-heavy course (health services, program evaluation, advanced epi, etc.).

- Balanced strength: strong performance in traditional sciences and in quantitative public health methods, with thoughtful electives in policy, disparities, and systems.

- A coherent narrative: your essays and activities reference concrete experiences and skills that are visibly anchored in your coursework, not just generic statements about “population health” or “health equity.”

If you build your course plan with that structure in mind, “Public Health” on your major line will not just look different on paper; it will signal to admissions committees that you are already thinking like the kind of physician they want to train.

FAQ (Exactly 6 Questions)

1. Will majoring in public health hurt my chances compared with a “hard science” major?

No, provided your science coursework and MCAT scores demonstrate competence. Many adcoms view public health majors favorably because they bring systems thinking and an understanding of determinants of health. The problem is not the major itself; the problem arises when applicants use public health to avoid challenging science or quantitative courses. If you show strong performance in the core sciences and rigorous public health methods, your major is an asset, not a liability.

2. If I can only fit one methods course, should I choose biostatistics or epidemiology?

Epidemiology is usually more directly useful for interpreting clinical literature and understanding screening, risk, and causality, so if you are forced to choose, Epi often has a slight edge. However, from a pure MCAT and “data literacy” standpoint, Biostatistics is also extremely valuable. The optimal sequence is Biostats first, then Epi, but if scheduling prevents that, an Intro Epi course with some embedded stats can still be very impressive.

3. Do online or community college public health courses carry the same weight?

They generally carry less weight than in-residence, upper-division courses at a four-year institution, especially for methods-heavy topics. An online “Intro to Public Health” from a community college will not count against you, but it also will not impress the way a 300- or 400-level Epi or Biostats course at your primary university will. Use community college to cover basic requirements if necessary, but try to take your most rigorous methods and policy work at your home institution where the grading and depth are better trusted.

4. How many public health courses should I take if I am not majoring or minoring in it?

If you are, say, a Biology or Chemistry major but want a visible public health orientation, a very strong pattern would be 4–6 targeted courses: Intro to Public Health, Biostatistics (preferably biostats-in-health), Epidemiology, one course in Social/Behavioral determinants or disparities, and one course in Health Policy or Health Systems. That set alone can convincingly anchor a “population health” narrative without a formal major or minor.

5. Is an undergraduate public health major redundant if I plan to do an MD/MPH later?

Not redundant, but complementary. Undergraduate public health gives you conceptual frameworks and introductory methods; an MPH provides depth, specialization, and often more sophisticated analytic training plus practicum experience. For MD/MPH programs, having a strong undergraduate public health background can make you stand out as highly prepared. Just ensure your undergraduate degree does not become overly narrow at the expense of core sciences and broader intellectual development.

6. How do I know if a public health course is considered “rigorous” by adcoms?

Look at several indicators: the course level (300/400-level tends to be more respected than 100-level surveys), prerequisites (does it require stats, methods, or previous public health courses?), assignments (data analysis, policy briefs, longer papers versus only quizzes), and the use of software (R, Stata, SPSS). You can also check where the course sits in your department’s curriculum map. If it is required for the major and listed as a “methods” or “core” course, adcoms are more likely to see it as rigorous than if it is an unrestricted elective with no prerequisites.