The most common advice about gap years is wrong: the number of gap years matters far less than what you do with them—and the data backs that up.

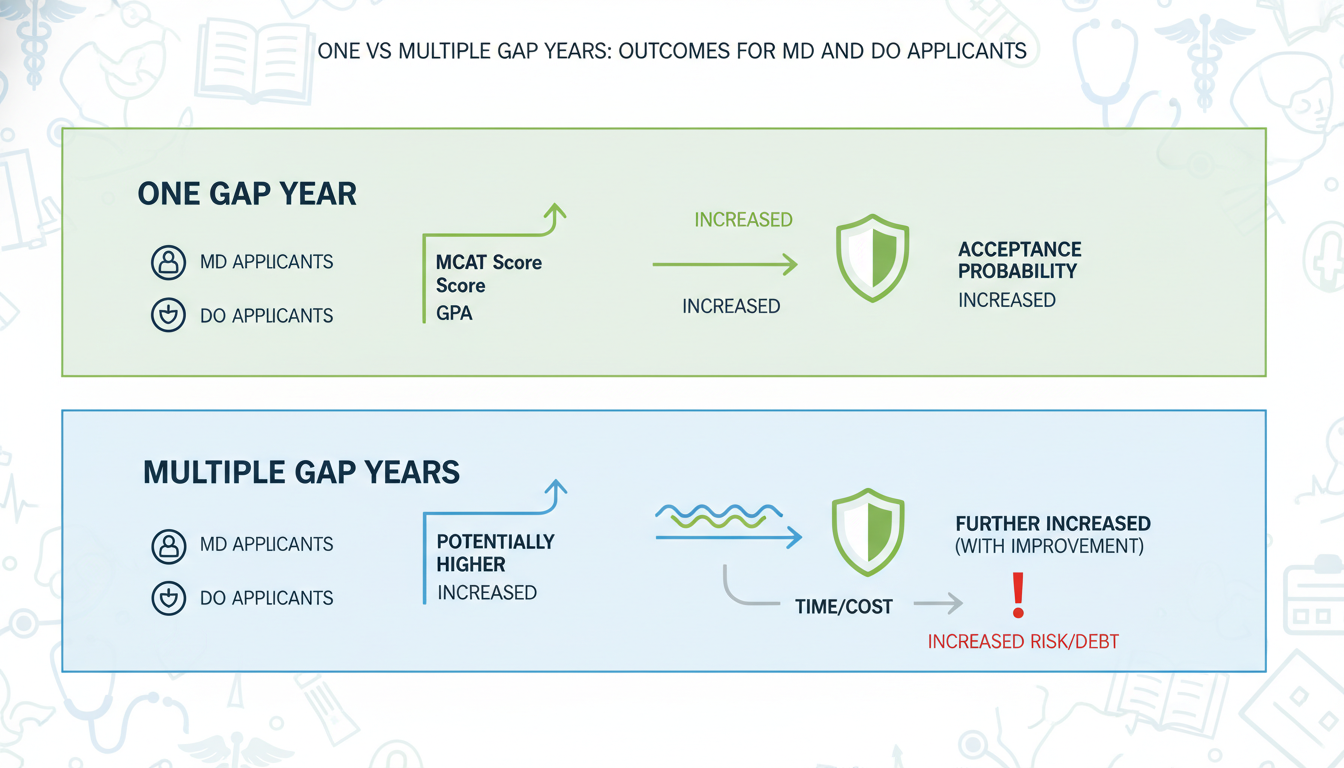

For both MD and DO applicants, outcomes are driven by measurable changes in your application profile: MCAT, GPA trends, clinical hours, research productivity, and the strength of your narrative. One gap year versus multiple gap years is a strategic variable, not a moral failing or badge of honor.

This article examines what the numbers show about 0, 1, and 2+ gap years, and how outcomes differ for MD vs DO pathways.

(See also: Acceptance Rates by Undergraduate Institution Type for more details.)

1. What the Data Actually Shows About Gap Years

There is no single “Gap Year Report,” but multiple large datasets give us clear directional evidence:

- AAMC: “Matriculating Student Questionnaire,” “FACTS” tables, and age distributions for U.S. MD students

- AACOM: “Entering Student Surveys,” COM data reports for U.S. DO students

- Published analyses: age at matriculation, odds of acceptance per applicant cycle, and relationships among MCAT, GPA, and outcomes

MD applicants: gap years are now the norm, not the exception

Take age first. AAMC data show:

- Median age of first-year MD students: 23

- The majority of matriculants are not straight through (i.e., they have at least 1 gap year)

- Only about 1/3 of matriculants go directly from college to MD matriculation (0 gap years)

If you graduate at 22 and matriculate at 23, you have one gap year by definition.

Now look at acceptance rates. From recent AAMC application cycles:

- Overall MD acceptance rate: roughly 40–43 percent of applicants are accepted in any given cycle

- Reapplicants (those who effectively took at least 1 “forced” gap year) have lower acceptance in the next cycle if their metrics do not improve

However, when you stratify by metrics, the pattern changes:

- Applicants who improved MCAT by ≥3 points between cycles had meaningfully higher acceptance odds than those who reapplied with unchanged scores

- GPA trend (upward during post‑bacc or SMP) strongly correlates with higher interview and acceptance rates, particularly for those who started with weaker GPAs

In other words, gap years that change numbers change outcomes.

DO applicants: more non‑traditional, more gap years, similar logic

DO matriculants skew older and more “nontraditional”:

- Median age of first-year DO students: closer to 24

- A larger fraction have 2+ years between undergrad and matriculation

- A higher share completed career changes, post‑baccs, or SMPs

Aggregate DO acceptance rates are harder to interpret, since many applicants apply both MD and DO. But DO schools:

- Often place relatively more emphasis on clinical experience, shadowing, and mission fit

- Are commonly more receptive to significant academic repair via post‑bacc or SMP, which usually requires 1–2+ gap years

Again, the data story is identical: outcomes move when metrics and experiences move, not when the calendar advances.

2. 0 vs 1 vs 2+ Gap Years: Quantitative Tradeoffs

You are not deciding between “good” (no gap year) and “bad” (multiple gap years). You are choosing among different probabilistic paths, each with distinct statistical profiles.

Let us define:

- 0 gap years: matriculate the same year you graduate

- 1 gap year: apply during senior year or soon after, matriculate one year after graduation

- 2+ gap years: at least two full cycles between graduation and matriculation (or multiple unsuccessful cycles)

Scenario modeling: MCAT, GPA, and acceptance odds

Use approximate, data-aligned patterns for MD applicants, recognizing that each cycle’s exact numbers vary.

Baseline applicant:

- cGPA 3.55, sGPA 3.45

- MCAT 508

- Decent but not exceptional experiences

Using historical AAMC acceptance curve patterns:

- At 3.4–3.6 GPA and 507–509 MCAT, aggregate MD acceptance probability is roughly 30–40 percent, depending on school list and state of residence.

Path A: No gap year, apply once, do not improve metrics

If you apply once with these baseline stats and get one shot:

- Expected probability of acceptance over that one cycle: ~0.35 (35 percent)

- Risk: If you miss, the next application is as a reapplicant, which statistically lowers odds unless your profile changes

Total expected outcome across your career then hinges on what happens in reapplication cycles.

Path B: One gap year, targeted metric jump

Say you take 1 deliberate gap year and:

- Improve MCAT from 508 → 513 (+5)

- Raise sGPA via 24 post‑bacc credits from 3.45 → 3.55

- Add 1,000 hours of paid clinical work

On AAMC MCAT–GPA acceptance grids:

- MCAT 513 with GPA in the 3.5–3.6 range moves you into a band with ~55–60 percent acceptance probability for MD (again, assuming a rational school list)

Now your first application cycle has ~0.58 chance of acceptance rather than 0.35.

Mathematically, you have:

- No‑gap path: P(accept) ≈ 0.35 in first attempt

- One-gap path: P(accept) ≈ 0.58 on first attempt, with better odds for DO as well

Across thousands of applicants, that ~20+ percentage point difference is huge.

Path C: Two+ gap years with major academic repair

Consider a more constrained starting point:

- cGPA 3.1, sGPA 3.0, MCAT 498

- Very low chances for MD, modest for DO if mission-aligned

Historical MD data:

- At GPA 3.0–3.2 and MCAT < 500, acceptance for MD is in the single digits. It is effectively a <10 percent event unless something dramatic changes.

If you commit to 2 gap years:

- Year 1: 30–32 post‑bacc credits at 3.8–4.0 → cGPA rises to ~3.3–3.35

- Year 2: MCAT retake from 498 → 508

- Clinical and volunteer gaps closed

Now you sit roughly in the:

- 3.3–3.4 GPA, 506–508 MCAT band, where MD acceptance rates might be in the 25–35 percent range

- For DO, those stats become quite competitive, often >50 percent acceptance for a well-constructed applicant pool

Two conclusions follow:

- One or two high‑impact gap years can easily double or triple your acceptance probability compared with rushing in underprepared.

- Multiple low‑impact gap years with little change in MCAT/GPA or experiences show negligible improvement in outcomes and often worsen your narrative.

3. MD vs DO: How Gap Year Patterns Differ in Practice

MD programs: higher MCAT, more research, earlier application advantage

Median MD matriculant stats:

- GPA: ~3.75 (total), ~3.7 (science)

- MCAT: ~511–512 (depending on year)

A single gap year for MD applicants is often used to:

- Retake the MCAT (typical jump: 3–7 points when done correctly)

- Increase research exposure to be competitive at mid‑to‑upper tier programs

- Strengthen clinical and nonclinical experiences to demonstrate readiness

The data here is clear:

- Applicants with MCAT ≥515 and GPA ≥3.8 have >75 percent acceptance rates across the pool

- Applicants with MCAT ≤502 and GPA <3.4 often sit below 20 percent MD acceptance odds

The “leverage” of a gap year is highest when you are in a middle band where improvement is possible. For example:

- From 504 → 511 MCAT with stable GPA can more than double your acceptance odds

- From 510 → 517 MCAT at GPA 3.8+ can shift you from “some MDs” to “many MDs including more competitive ones”

DO programs: more flexibility for academic repair, greater tolerance for multiple gap years

Median DO matriculant stats:

- GPA: around 3.55–3.6

- MCAT: around 503–505 (varies by school and year)

The DO pathway often attracts:

- Applicants with lower initial GPAs or MCATs

- Career changers with prior work histories

- Students who completed post‑baccs or SMPs after multiple gap years

Here, multiple gap years are not unusual. But the same quantitative rule applies:

- Moving from 495 → 504 MCAT and 3.2 → 3.5 GPA via post‑bacc and retake can transform DO acceptance odds, pushing them into the 50–70 percent range at many schools

- Reapplying with 495 and 3.2 repeatedly has diminishing returns and can push you below 20 percent

DO schools often value:

- Consistent upward trends (e.g., last 40–60 science credits at ≥3.7)

- Substantial direct patient care hours in PA, MA, EMT, CNA, or scribe roles

- Strong alignment with osteopathic philosophy and primary care

Those items usually take time—often more than a single gap year.

4. One vs Multiple Gap Years: Pattern Analysis by Applicant Type

Let us break this down by typical applicant profiles. The numbers are generalized but grounded in known acceptance curves.

Strong-stat applicant (MD-leaning)

Profile:

- GPA: 3.8–3.9

- MCAT: 515–520

- Experiences: moderate clinical, modest research, some leadership

- Risk: Under-optimized school list or weak narrative

For this group:

- Zero gap years: MD acceptance probability often 75–85 percent across a reasonable school list

- One gap year: Might help convert “some mid‑tiers” into “more top‑tiers” through added research and publications, but the marginal gain is often prestige, not “any acceptance”

Multiple gap years usually show diminishing quantitative returns unless you are aiming for highly research‑intensive MD programs (e.g., wanting to move from generic MD acceptance to MD/PhD or top‑10 programs).

Middle-band applicant (borderline MD, strong DO)

Profile:

- GPA: 3.4–3.6

- MCAT: 503–508

- Experiences: decent, but not stellar

- Risk: Falling into the 20–40 percent MD acceptance band, 40–70 percent DO band

One focused gap year can:

- Shift MCAT into 510–512 range

- Boost recent GPA through post‑bacc coursework

- Increase clinical and nonclinical hours to levels competitive for MD

Empirically, moving from the 503–505 to 510–512 MCAT range with similar GPAs raises MD acceptance from “coin flip at best” to “probable, with an intelligent list.” If you also refine your essays and letters, the total impact can easily double your odds.

Multiple gap years may be warranted if:

- Your GPA is on the low end (3.3–3.4) and you need 1–2 years to establish a strong upward GPA trend

- You initially underestimate the work needed and your first gap year produces only minor changes (e.g., MCAT +1, minimal new coursework)

Under‑threshold applicant (needs major academic repair)

Profile:

- GPA: ≤3.3

- MCAT: ≤500

- Risk: Statistically low MD odds, uncompetitive DO odds without significant changes

For this group, the data supports a 2+ year rebuild strategy more than a rushed application:

- MD acceptance below these thresholds is often <10–15 percent

- DO acceptance is more forgiving but still harsh below MCAT 498 and GPA <3.2

The quantitatively rational path usually looks like:

- Year 1–2: Post‑bacc or SMP, 30–40+ credits at 3.7–4.0, raising cumulative GPA toward 3.3–3.5

- Exam prep: MCAT from sub‑500 to 505–508

- Experiences: 1,000–2,000 hours clinical over 2–3 years

At that point:

- DO acceptance odds are often very favorable (50–75 percent)

- MD odds may climb into the 25–40 percent band, depending on final metrics

Yes, this is 2–3+ gap years. But from a probability perspective, it changes the entire distribution of outcomes.

5. Hidden Quantitative Factors: Reapplication, Burnout, and Narrative

Gap years are not just linear time. The interaction with reapplication status is critical.

Reapplicant penalty vs improvement bonus

Data from AAMC and school reports show:

- Reapplicants, on average, have lower acceptance rates than first‑time applicants

- However, reapplicants who significantly improve metrics and experiences often match or exceed first‑time applicants with comparable final stats

The “penalty” is not about being a reapplicant. It is about being a stagnant reapplicant.

Quantitatively:

- Reapplying with MCAT +0, GPA +0.02, similar hours → very small gain in acceptance probability, sometimes negative when schools perceive lack of growth

- Reapplying with MCAT +4–5, 200–500+ new clinical hours, improved LORs → substantial gain, often akin to being a stronger first‑time applicant

This is where multiple gap years can hurt or help:

- Two years of low‑change stagnation signals plateau

- Two years of high‑intensity growth produces a very different data point

Burnout and time to attending: a less obvious calculation

Some applicants worry that extra gap years “delay their life.”

If you start medical school at:

- Age 22 (0 gap): finish at ~26, residency completion often ~29–32

- Age 24 (2 gap years): finish at ~28, residency completion often ~31–34

The difference is 2 years in a 30–40 year career. If those 2 years shift your trajectory from:

- No acceptance → eventual acceptance

- or

- Marginal DO choices → broader MD+DO options

the net present value of that delay is often strongly positive.

Conversely, if an extra gap year does not materially change your metrics or mental health, you traded one year of attending income for very little additional probability of a desired outcome. The expected value equation becomes unfavorable.

6. How to Decide: A Data-Driven Framework for Your Situation

Instead of starting with “how many gap years,” start with quantifiable targets. Then ask how much time is statistically required to reach them.

Step 1: Benchmark your current numbers

List:

- Cumulative GPA and science GPA

- Number of recent science credits and their trend (last 30–60 credits GPA)

- MCAT score (or practice test average if not yet taken)

- Current clinical, nonclinical, research, and shadowing hours

Then place yourself on approximate MD and DO acceptance curves:

- MD: Compare your GPA/MCAT to AAMC FACTS “Acceptance by MCAT and GPA” tables

- DO: Compare to common matriculant stats (GPA ~3.5–3.6, MCAT ~503–505) while remembering that many DO schools evaluate last‑60‑credits trends heavily

Step 2: Define realistic improvement deltas

The data and test‑prep outcomes suggest:

- MCAT: Reliable, well‑planned retakes can yield 3–7 point jumps; >10 is rare and risky

- GPA: With a large existing credit load (e.g., 120+ credits), moving overall GPA by 0.2 points can require 40–60 credits of 3.8–4.0 work

So ask:

- Can I realistically raise my MCAT from 503 → 510 in one dedicated gap year? Very possible.

- Can I raise my cGPA from 3.1 → 3.5 in one year? No, the math rarely allows that. You likely need 2+ years or an SMP.

Match these constraints with your goals (MD‑only, MD+DO, DO‑only).

Step 3: Choose the number of gap years that fits the math, not the ego

You essentially choose among:

One gap year when:

- MCAT improvement of 3–7 points would put you into a substantially stronger acceptance band

- GPA is already near or above common medians

- Experiences need depth, not an entirely new foundation

Two or more gap years when:

- You need 30–60+ credits of 3.7–4.0 work to repair GPA

- You must undergo a major MCAT repair (e.g., sub‑500 to 505–510)

- You are changing careers, starting from minimal clinical exposure

Zero intentional gap years (applying straight or immediately after graduation) when:

- Your metrics already sit comfortably above typical matriculant ranges

- The marginal gain from waiting is prestige, not acceptance itself

7. MD vs DO Strategy: Practical Combinations of Gap Years

A few data‑consistent strategic patterns emerge:

MD‑first, DO‑open, 1 gap year strategy

- Use 1 gap year to optimize MCAT and experiences

- Apply broadly to MD and DO in the following cycle

- Expected outcome: high probability of at least DO matriculation, decent probability of MD

DO‑focused, 1–2 gap year repair

- Concentrate on strong final‑2‑years GPA and moderate MCAT improvement (e.g., 495 → 503)

- Accumulate 1,000–2,000 clinical hours over 1–2 gap years

- Expected outcome: strong competitiveness at multiple DO schools, possible MD interviews if final MCAT reaches 507+ and GPA 3.4+

MD‑only, major academic rebuild (2–3+ gap years)

- Commit to a formal post‑bacc or SMP

- Aim for MCAT ≥510 and last‑60‑credits GPA ≥3.7

- Expected outcome: meaningful MD competitiveness after multiple high‑impact years, though risk remains

Each path is a different combination of time and probabilistic gain.

Key Takeaways

- The number of gap years matters far less than how strongly each year moves your MCAT, GPA, and experience profile; high‑impact gap years can double or triple your odds, while stagnant years add almost nothing.

- MD and DO programs differ slightly in age patterns and academic thresholds, but both reward clear upward trends and measured improvements; multiple gap years are most valuable for academic repair and career changers.

- Choose 0, 1, or 2+ gap years based on what the math says about your needed MCAT/GPA shifts and experience gaps, not on fear of being “behind”—the data favors strategic delay over rushed, underpowered applications.