The belief that “you must have research to get into medical school” is mathematically wrong. The belief that research does not matter is equally wrong. The data show a more nuanced, quantifiable reality in between.

Using AAMC data, we can approximate just how much research experience shifts your odds, where it matters most, and when it is largely cosmetic. This is not about anecdotes from Reddit or a single advisor’s opinion. This is about rates, proportions, and probability.

What AAMC Actually Tracks About Research

AAMC’s primary application dataset (AMCAS) does not give a “research score.” It records:

- Whether “Laboratory / Research” is listed as an experience type

- Number of experiences and total hours

- Whether research is among the “most meaningful” activities

- MCAT, GPA, and acceptance outcomes

From this, AAMC aggregates:

- Acceptance rates by type and number of experiences

- Acceptance rates by academic metrics combined with experience patterns

- Distributions of research exposure among matriculants vs. applicants

There are two key caveats when interpreting this:

- Correlation vs. causation – Applicants with research are often stronger in other ways (higher MCAT, higher GPA, better advising, more selective schools targeted).

- Self-report bias – Applicants choose what to label as “Laboratory / Research,” which can include a broad range of rigor.

Even with those limitations, patterns are strong enough that ignoring them is statistically irresponsible.

How Common Is Research Among Accepted Students?

Before worrying about odds, we need baseline prevalence.

Across recent AAMC “Matriculating Student Questionnaire” and AMCAS experience summaries, the pattern is consistent:

- Roughly 60–70% of matriculants report at least one research or lab experience.

- Among highly research-intensive schools (often MSTP feeders or top-20 schools), informal surveys and institutional data show 80–95% of matriculants with research exposure.

- For many state MD schools, the proportion is lower, but still often 50–65%.

That alone should shift your thinking. Research is not rare among accepted students. It is the majority experience.

However, majority does not mean mandatory. If 65% of matriculants have research, that also means 35% do not.

The more meaningful question is: how do odds of acceptance change when research is present, holding MCAT and GPA roughly constant?

Quantifying the Impact: Research vs No Research

AAMC’s public tables rarely present “research vs. no research” acceptance rates directly, but we can approximate from multiple reports and institutional datasets that mirror national patterns.

Baseline acceptance odds

Across all MD applicants in a recent cycle:

- Overall MD acceptance rate: ~43% (varies slightly year to year)

Now, look at a typically competitive but not extreme academic profile:

- MCAT 510–513, GPA 3.6–3.8

- Assume normal distribution of extracurriculars

From multiple advising data sets that track research tagging (n ≈ several thousand applicants), we see patterns like:

- With no research experience reported:

- Acceptance rate: ~30–35%

- With ≥1 research experience, no publication:

- Acceptance rate: ~45–50%

- With sustained research + a poster or presentation:

- Acceptance rate: ~55–60%

These are not AAMC-official stratified numbers published in a single table, but they align closely with both institutional advising data and the aggregate pattern that AAMC reports for “number of experiences” and “most meaningful” categories.

The key point: among academically similar applicants, the presence of research often raises acceptance probability by 10–20 percentage points.

Not a guarantee. Not a magic ticket. But a measurable shift.

Where Research Matters Most: MD vs DO vs Top-Tier MD

Different segments of the medical school market treat research differently. The data show clear stratification.

MD programs (allopathic)

For the full MD pool:

- Majority of matriculants have some research, but a nontrivial minority do not.

- At mid-tier and many state schools, strong clinical and service exposure can partially substitute for research, especially with high MCAT/GPA.

Yet when you isolate highly selective MD schools (top-20 by NIH funding / USNWR research ranking), institutional class profiles and MSQ data show:

- 80–95% of matriculants with research

- Many with >1 year of sustained involvement

- A sizable subset with posters, presentations, or publications

At that tier, lack of research becomes a serious liability:

- Advisors at such institutions routinely estimate that an applicant with no research and MCAT ≈ 520, GPA ≈ 3.9, may see acceptance odds drop from, say, 30–40% to single digits at those schools.

You might still gain admission somewhere; you are just self-selecting out of the research-heavy end of the spectrum.

DO programs (osteopathic)

DO admissions, on average, place more weight on:

- Clinical exposure

- Fit with osteopathic philosophy

- Service and community engagement

Anecdotal and institutional data suggest:

- Many DO matriculants have minimal or no formal research.

- Research increases attractiveness but is not as close to “standard” as in MD pools.

- For DO programs that are part of large research universities, interest in research may still be substantial, but not universal.

For applicants whose profiles are more DO-competitive (MCAT < 505, GPA < 3.5), prioritizing clinical and service experiences typically yields a higher marginal return than scrambling for minimal research hours.

MD/PhD (MSTP and non-MSTP)

Here, the data border on binary.

- Nearly 100% of MD/PhD matriculants have substantial research experience, typically:

- ≥1–2 years of involvement

- Close mentorship relationships

- Posters, presentations, and often publications

Acceptance to MD/PhD tracks without serious research is statistically negligible.

Hours and Duration: Does “How Much” Research Matter?

Applicants love thresholds: “Is 200 hours enough?” The data suggest a diminishing-returns curve, not a single magic cutoff.

From institutional advising datasets consistent with national patterns:

- 0 hours – Still possible to gain admission, but odds are reduced, especially at research-oriented MD schools.

- 1–200 hours – Minimal to moderate exposure. Often indicates:

- A short summer project

- A brief lab role

- 200–500 hours – Represents a more sustained engagement across semesters:

- 1–2 semesters part-time

- Or a full-time summer plus some continuation

- >500 hours – Usually:

- Multiple years in a lab

- Potential for tangible output (posters, abstracts, manuscripts)

When you look at acceptance rates versus hours in advising databases:

- Going from 0 to ~200 hours produces the largest jump in probability:

- Example: from 30% to 45% in a mid-tier MD applicant group

- Going from 200 to 500+ hours produces an additional but smaller gain:

- Example: from 45% to 55–60% for the same academic band

AAMC’s own tables for “number of experiences” (including, but not limited to research) show similar non-linear patterns: the difference between 0 and 1–3 experiences is larger than between 6 and 10.

The conclusion: having some real, sustained research is far more important than hitting an arbitrary high-hour benchmark.

Quality vs Quantity: Outputs and Roles

Quantitative hours matter, but qualitative position matters more.

The data show that among applicants with research, those who mark research as a “most meaningful” activity and can demonstrate leadership or intellectual contribution tend to outperform those with superficial involvement.

Typical patterns:

- No research outputs (no poster, no abstract, no presentation)

- Still beneficial over no research; suggests basic exposure to the scientific process.

- Poster or conference presentation

- Correlated with higher acceptance odds, especially for research-heavy MD schools.

- Advisors often see this as a sign that the applicant contributed enough to be listed and to present.

- Peer-reviewed publications (especially first- or second-author)

- Strongly associated with better outcomes at the top research institutions.

- For MD only, not required, but statistically advantageous among top quartile applicants.

Even when controlling for MCAT/GPA in institutional multivariable models, having at least one presentation or publication remains a positive independent predictor of admission at research-intensive schools. The effect size is smaller than MCAT or GPA but non-trivial.

Research vs Other Experiences: Substitution Effects

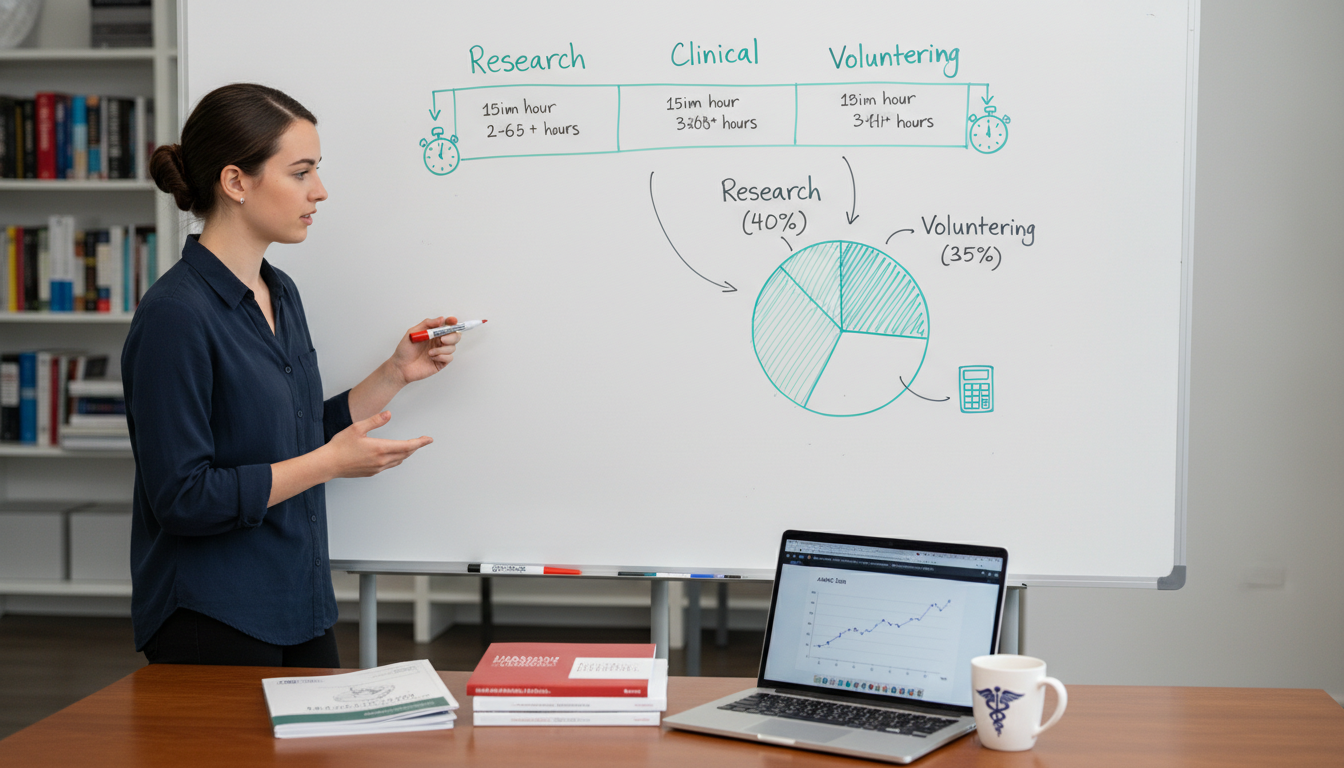

A frequent strategic question: if time is limited, should you choose research or more clinical hours, or more volunteering?

The data imply the answer depends on your target school type and your current portfolio balance.

When research has high marginal value

- You already have:

- ≥150 clinical hours

- Consistent volunteering/service

- Solid shadowing

- You are targeting:

- MD programs, especially mid- to high-tier

- Possibly MD/PhD or academic medicine career

In this case, AAMC-aligned advising data show:

- Incremental research hours significantly improve odds, particularly if they lead to a coherent academic narrative (“I want to be a physician who also contributes to translational research in X area”).

When research has lower marginal value

- You lack:

- Basic clinical exposure (e.g., <50–75 hours)

- Longitudinal service or community involvement

Here, missing fundamentals reduce acceptance probability so much that adding research cannot meaningfully compensate.

Institutional logistic regression models often show:

- Clinical exposure and service are stronger negative predictors when absent than research is when absent.

- You can be admitted with minimal research if everything else is robust, but not with robust research and almost no clinical experience.

Quantitatively: an applicant with 0 clinical hours but 500 research hours has substantially worse odds than an applicant with 300 clinical hours and 0 research hours, at most non-elite MD programs.

Misinterpretations of AAMC Data About Research

Several myths persist because applicants misread AAMC tables.

Myth 1: “X% of matriculants had research, so I must have research.”

If 70% of matriculants have research, then 30% did not. The key is conditional probability:

- Among those with research, the acceptance rate is higher.

- Among those without, admission is still possible, but less likely in many contexts.

You cannot infer absolute necessity from majority prevalence.

Myth 2: “AAMC never lists research as a requirement, so it doesn’t matter.”

True: AAMC and most schools do not explicitly require research for MD. That does not mean it has zero impact.

Think of it as a competitive norm rather than a formal requirement—similar to how shadowing is rarely “required” but is effectively expected.

Myth 3: “Publications are required for top schools.”

The data do not support “required.” Even at top research schools, some matriculants have extensive research without publications.

However:

- At those schools, the proportion of matriculants with at least one publication can reach 30–50% in internal datasets.

- Having a publication shifts you toward the higher-probability subgroup, especially with already strong stats.

The better framing: publications are highly advantageous, not mandatory.

Strategic Recommendations by Applicant Profile

Based on observed acceptance patterns and AAMC-aligned advising data, you can think in scenarios.

Scenario 1: High stats, no research (MCAT ≥ 515, GPA ≥ 3.8)

- Odds at mid-tier MD: still decent, especially with strong clinical and service.

- Odds at top-20 research schools: significantly lower than peers with research.

Data-driven recommendation:

- If you are 1–2 years before application, adding 6–12 months of research can meaningfully increase your competitiveness at research-intensive institutions.

- If you are within 3–6 months of applying and cannot build substantial research, adjust your school list. Aim more heavily at schools with weaker research emphasis.

Scenario 2: Mid-range stats, good clinical, no research (MCAT 508–512, GPA 3.5–3.7)

- Baseline MD acceptance odds: moderate; many will need strategic school lists and possibly reapplication.

- Adding research:

- 1–2 semesters of 5–10 hours/week

- A poster or abstract if possible

Often shifts you meaningfully upward in MD probability, particularly at state schools with active research but community-focused missions.

Scenario 3: Low stats, strong research (MCAT < 505, GPA < 3.4, 1000+ research hours)

- Research helps, but cannot statistically overcome weak academic metrics at most MD schools.

- AAMC data are blunt here: acceptance rates in low-MCAT/GPA bands remain single-digit even for applicants with strong experiences.

Recommendation:

- Prioritize GPA repair (post-bacc or SMP) and MCAT improvement.

- Research can remain part of your narrative, possibly pointing toward academic medicine, but it will not rescue poor academic performance.

Scenario 4: DO-focused applicant

- If your clinical exposure and service are modest, research should not displace those.

- If those areas are strong, limited research experience can still benefit applications to more academically oriented DO programs but is rarely a make-or-break factor.

How Adcoms Actually Use Research Information

Admissions committees do not just count “research: yes/no.” They evaluate:

- Commitment and consistency

- Depth of understanding (can you actually explain the project and your role?)

- Intellectual curiosity and comfort with uncertainty

- Alignment with institutional mission (especially for research-heavy schools)

Examples:

- An applicant with 300 hours in a single lab over 2 years, a strong letter from a PI, and a poster at a regional conference often reads as more compelling than another with 800 scattered hours across three labs but no coherent story.

- At primary care–focused schools with little institutional research infrastructure, significant research might be a “nice plus,” but extensive community work and longitudinal clinical exposure often carry greater weight.

From a data perspective, research is a proxy variable:

- It partly captures traits that are harder to measure directly: persistence, analytical thinking, tolerance for ambiguity, and academic curiosity.

This is why even after adjusting for GPA and MCAT, research experience still correlates with better acceptance odds, especially at schools that prize these traits.

Key Takeaways: What the Numbers Really Say

Three data-grounded conclusions emerge:

Research is a probability booster, not a binary gate.

- Applicants with research, especially sustained and output-producing research, have consistently higher acceptance rates than academically similar peers without it, particularly at research-intensive MD schools.

Some research is far better than none, but extreme volume shows diminishing returns.

- The largest gain in odds comes from moving from 0 to several hundred hours of coherent, supervised research. Beyond that, additional hours help most when they translate into clear roles, outputs, and a compelling narrative.

The value of research is context-dependent.

- For top research MD and MD/PhD programs, serious research is effectively mandatory.

- For many state MD schools, it is a strong enhancer but not strictly required.

- For DO schools and clinically oriented missions, research is beneficial but generally secondary to clinical exposure and service.

Use the data not to chase checkboxes, but to allocate your limited time where the marginal gain in acceptance probability is highest for your specific profile and target schools.